Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4692

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4692)

The Effect of Bleaching Agent Application on the Color Change of Fiber-Reinforced Composites Volume 3 - Issue 1

Makbule Tugba Tuncdemir*

- Department of Restorative Dentistry, Turkey

Received: August 03, 2018; Published: August 09, 2018

Corresponding author: Makbule Tugba Tuncdemir, Necmettin Erbakan University, Department of Restorative Dentistry, Turkey

DOI: 10.32474/MADOHC.2018.03.000153

Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of a home-belaching (16% carbamide pereoxide) agent on color change in aged anterior / posterior composite samples with or without fiber reinforcement. Two different composites, one anterior and one posterior, a home bleaching agent and polyethylene fiber were used. All samples were prepared with 8 mm wide and 4 mm high teflon molds. Polyethylene fiber was incorporated in the middle of the samples in fiber groups. The samples were kept in distilled water for a total of 14 days, inıtial color measurements were made. After aging, bleaching agent was applied for 14 hours daily for 4 hours. Color measurements were repeated. Data were statically analyzed by using One-way ANOVA and t-test. Anterior composites’ delta e values after bleaching were not statistically significant between fiber group and control group without fiber (p>0,05). Posterior composites’ delta e values after bleaching were statistically significant between fiber group and control group without fiber (p<0,05). The fiber group had lower delta e values.

Color change after bleaching was less in the fiber group (p = 0,001). Fiber addition had negatively affected the penetration and activity of the bleaching agent on posterior composite. Home bleaching agent was affected both anterior and posterior composite. It should be informed that the bleaching procedures are effect of external colorings, but composite fillings cannot appear as white as natural teeth after bleaching.

Introduction

The use of composites has become increasingly widespread in recent years with the increasing aesthetic expectation of patients and aesthetic similar to natural teeth. Fiber reinforced composites are used not only in the front regions but also in the back regions where the material loss is high. It reduces both the cost and the number of sessions and shortens the time the patient has spent on the seat. Fiber-reinforced composite restorations have higher flexural strength and are more durable [1]. Composites are prone to color change. After a period of time, the patients begin to feel uncomfortable with this colored filling [2]. Color change is one of the criteria that the composite needs to be renewed. Colors based on composite material structure are classified as ‘internal colorings’, while mistakes associated with application are classified as ‘external colors’ [3]. Replacing a colored composite restoration can cause unnecessary loss of material from the dental tissue. Instead of replacing the filler, surface polishing or bleaching may be preferred [4-5]. There are a lot of studies showing that polishing and surface conditioning removes external coloring. It has been shown that office-type and home-applied bleaching agents containing hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide, which are used as active ingredients in whitening, are also effective in dental coloring [6-13]. Bleaching can be applied in cases where the exterior colorings are resin matrix or the colorings formed by oxidation of the materials of the composite contents. Whitening agents enable these colored areas to be removed [14-16]. The effect of the bleaching agents on the composite resins depends on the type of composite as it depends on the concentration of the bleaching agent [17-20]. We do not have much literature knowledge about the effect of these bleaching agents on the color change of composites.

Munsell and the CIE Lab (Commission International de l’Eclairage) color systems are generally used to evaluate color differences. The most widely used color measurement system is the CIE Lab system [21]. Artificial aging methods are applied in order to imitate the wearing time and wear time of a composite resin. One of the most commonly used artificial aging methods is water soaking. In this method, the samples are kept in the liquid for a predetermined time at 37 degrees [22-23]. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of a home-bleaching (16% carbamide Citation: Makbule Tugba Tuncdemir. The Effect of Bleaching Agent Application on the Color Change of Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Mod App Dent Oral Health 3(1)- 2018. MADOHC.MS.ID.000153. DOI: 10.32474/MADOHC.2018.03.000153. 222 pereoxide) agent on color change in aged anterior / posterior composite samples with or without fiber reinforcement.

Material and Methods

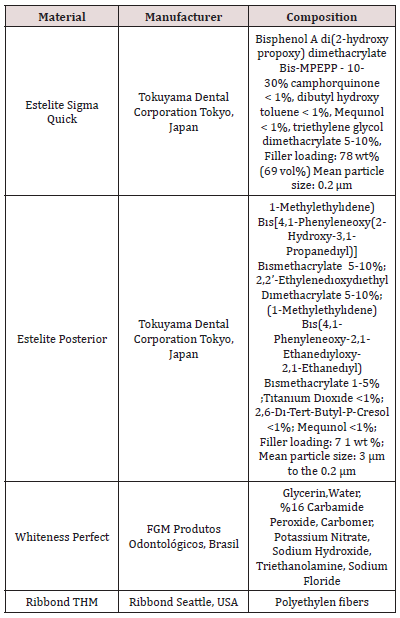

In our study, we used two different composites, one anterior and one posterior, a home bleaching agent and polyethylene fiber. The properties of the materials are given in Table 1.

Preparation of Samples

Ten samples of each composite were prepared with 8 mm wide and 4 mm high Teflon molds. Each composite was divided into two groups, with fibers and without fibers. Non-fiber groups were accepted as control groups. The samples in the control group were placed in two layers of composite, with transparent bands on the top and bottom, between two glasses, and each layer was polymerized with LED light device for 20 seconds. In fiber groups, the first layer composite 2 mm was placed in the center of the 4 mm thick teflon mold, 6 mm long and 4 mm wide fibers were cut and placed in the center of the sample with bonding impregnation and the second layer composite was placed and polymerized with LED light device.

Ageing Procedure

The samples were kept in distilled water for a total of 14 days (the solution was renewed every 3 days). Inıtial color measurements were made with a spectrophotometer (Figure 1).

Bleaching Procedure

After aging, 16% Carbamide Peroxide (Whiteness Perfect) were applied for 14 hours daily for 4 hours.

Color Measurement

In this study, CIELAB (Commission International L’Eclairage) color measurement system was used. According to this system, all colors are formed by intersection of 3 different axes. These axes are; L: vertical axis represents the brightness or aperture coordinates of white (+) - black (-),

a) Horizontal axis represents the chromatic coordinates between red (+) - green (-),

b) Horizontal axis indicates the chroma coordinates between yellow (+)- blue (-) [24-25].

After bleaching, color measurements were repeated. Before each measurement, the device was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was measured three times on a white background and averaged. Mean values were used in statistical analysis. Color measurements were repeated. Data were statically analyzed by using One-way ANOVA and t-test (P<0,05).

Results

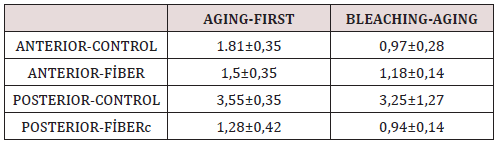

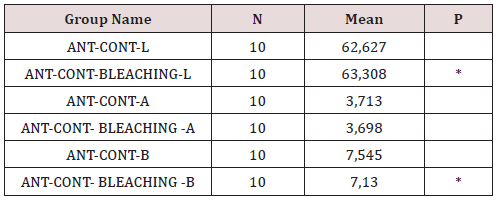

Anterior composites’ delta e values after bleaching were not statistically significant between fiber group and control group without fiber (p>0,05) (Table 2). Posterior composites’ delta e values after bleaching were statistically significant between fiber group and control group without fiber (p<0,05). The fiber group had lower delta e values. Color change after bleaching was less in the fiber group (P = 0,001) (Table 2). Anterior and posterior composites were statistically different when the fiber additions were compared in terms of post-aging color change (P = 0.001). The posterior composite is more colored than the anterior. Before and after bleaching, l and b values of the anterior control group without fiber were statistically different (P = 0.002). (P = 0.021). There was no statistical difference between a value (Table 3).

Table 3: The mean values and p values of color change after bleaching in the anterior control group (without fiber).

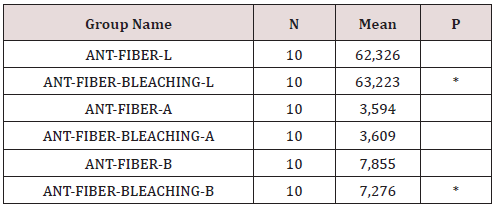

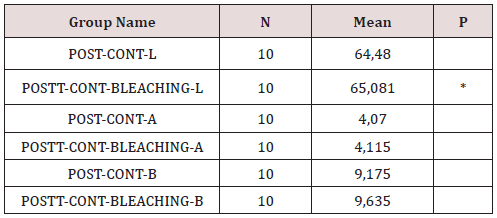

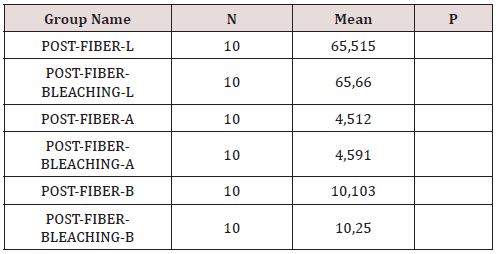

There was a statistically significant difference between l and b values after bleaching in the anterior composite fiber group. (P = 0.001). (P = <0.001). There was no statistical difference between a value (Table 4). There was a statistically significant difference between values after bleaching in the posterior composite fiber group. There was no statistically significant difference between a and b values (Table 5). No statistically significant differences were found in the values of l, a, b after bleaching in the posterior composite fiber group (Table 6).

Table 4: The mean values and p values of color change after bleaching in the anterior composite fiber group.

Table 5: The mean values and p values of color change after bleaching in the posterior composite fiber group.

Table 6: The mean values and p values of color change after bleaching in the posterior composite fiber group.

Discussion

Natural tooth image of the composites and long-term color stability are important in patients in whom aesthetics are important. Recent years the use of fiber-reinforced composites increases both anterior and posterior region. Removing the restoration may not always be the solution for the repair of the color change in the composites. Instead, bleaching treatments can be considered as an alternative. In this study, the response of bleaching was compared after aging on anterior and posterior composites (fibreless control group and fiber group). Factors influencing color determination are; the light in the environment, the light permeability of the material, the opacity, the reflection of light, the human eye that perceives the color [26]. The spectrophotometer, which was developed to reduce the most mistakes that may arise from these differences, has been chosen to be used in our work. In this way it is possible to calculate the ΔEab* values obtained by using the color parameters in the CIE L * a * b * color system and to reveal the color differences. The changes in color values can be evaluated in three different ranges according to human perception

a) ΔE <1: value of color change not perceivable by the human eye; 1.0 <ΔE <3.3: clinically acceptable color change value as determined by experienced persons

b) ΔE≥3.3: easily identifiable and clinically unacceptable color change value [27-30].

c) ΔE <3.3 values were determined as clinically acceptable values.

Bright and smooth composite surfaces are important for plaque retention, discoloration and secondary caries formation. It has been reported that bright and smooth composite surfaces are less colored than rough surfaces [31]. In our work, polish procedures were applied to all samples on equal conditions. In our study, ΔE values were 1.8-1.9 in control group without fiber in the anterior composite. It is between 1.2-1.5 in the fiber groups. ΔE values in posterior composite non-fiber control groups are between 3.2-3.5. It is between 1-3 in the fiber groups. Only posterior control groups’ delta e values before and after aging are above 3,3. The values in the other groups are clinically acceptable (ΔE <3,3). In a study, nanohybrid, hybrid and micro-fill composites were aged with water storage and the nanohybrid composite was reported to be more resistant to coloring [32].

In addition to Bis-GMA, composite resins containing UDMA have been reported to be more resistant to coloring [33]. In our work, when fiber addition was ignored, the hybrid composite (posterior) was statistically significantly more colored at the end of the aging than the nano hybrid composite (anterior). Some researchers argue that composite colorings can be partially removed by polishing and whitening procedures [33]. Bozkurt et al. reported that bleaching is a positive effect of color change [34]. We also found that bleaching had a positive effect on both anterior and posterior composite in our study. Composite matrix content, filler type and bulkiness are important in the response of composite resins to bleaching procedures [35]. In our study, the delta e values of fiber group were less changed than the control group in the anterior composite. Fiber group was less responsive to bleaching than control group. L and b values before and after bleaching were statistically different in all groups of anterior composite. There was no statistical difference between a value. Color change after bleaching was occurred, but the difference between fiber group and control group without fiber was not statistically significant.

In posterior composite, delta e values of fiber groups were statistically different according to the control groups without fiber. The fiber groups were less responsive to bleaching at a significantly higher rate than the control group. There was no statistically significant differences l, a, b values after bleaching in the fiber group of posterior composites. In the control group without fiber, statistical difference was found in the l values after the bleaching, and no difference was found in the values of a and b. Fiber addition had negatively affected the penetration and activity of the bleaching agent on posterior composite. Within the limitations of our study, bleaching activity was shown in both anterior and posterior composite groups, and the opening in the composite color was achieved. However, in the literature studies, the effect of coloring solutions cannot be completely solved by whitening. As a result, it should be informed that the bleaching procedures are effect of external colorings, but composite fillings cannot appear as white as natural teeth after bleaching. The option of replacing composite can be offered patient inserts with a high aesthetic expectancy.

References

- Fennis WMM, Tezvergil A, Kuijs RH, Lassila LVJ, Kreulen CM, et al. (2005) In vitro fracture resistance of fiber reinforced cusp replacing composite restorations. Dent Mater 21(6): 565-572.

- Barutcigil C, Yildiz M (2012) Intrinsic and extrinsic discoloration of dimethacrylate and silorane based composites. J Dent 40: 57-63.

- Nasim I, Neelakantan P, Sujeer R, Subbarao CV (2010) Color stability of microfilled, microhybrid and nanocomposite resins- -an in vitro study. J Dent 38: 137-142.

- Joiner A (2006) The bleaching of teeth: a review of the literature. J dent 34: 412-419.

- Turkun LS, Turkun M (2004) Effect of bleaching and repolishing procedures on coffee and tea stain removal from three anterior composite veneering materials. J Esthet Restor Dent 16(5): 290-301.

- Friend GW, Jones JE, Wamble SH, Covington JS (1991) Carbamide tooth bleaching: changes to composite resins after prolonged exposure. J Dent Res 70: 570.

- Cooley RL, Burger KM (1991) Effect of carbamide peroxide on composite resins. Quintessence Int 22: 817-821.

- Bailey SJ, Swift EJ Jr (1992) Effect of home bleaching products on composite resins. Quintessence Int 23(7): 489-494.

- Cullen DR, Nelson JA, Sandrik JL (1993) Peroxide bleaches: effect on tensile strength of composite resins. J Prosthet Dent 69(3): 247-249.

- Hunsaker KJ, Christensen GJ, Christensen RP (1990) Tooth bleaching chemicals-influence on teeth and restorations. J Dent Res 69: 303.

- Robinson FG, Haywood VB, Myers M (1997) Effect of 10 percent carbamide peroxide on color of provisional restoration materials. J Am Dent Assoc 128(6): 727-731.

- Monaghan P, Lim E, Lautenschlager E (1992) Effects of home bleaching preparations on composite resin color. J Prosthet Dent 68(4): 575-578.

- Monaghan P, Trowbridge T, Lautenschlager E (1992) Composite resin color change after vital tooth bleaching. J Prosthet Dent 67(6): 778-781.

- Ortengren U, Andersson F, Elgh U, Terselius B, Karlsson S (2001) Influence of pH and storage time on the sorption and solubility behaviour of three composite resin materials. J Dent 29(1): 35-41.

- Ardu S, Gutemberg D, Krejci I, Di Bella E, Dietschi D, et al. (2011) Influence of water sorption on resin composite color and color variation amongst various composite brands with identical shade code: an in vitro evaluation. J Dent 39(Suppl 1): e37- 44.

- Kim JH, Lee YK, Lim BS, Rhee SH, Yang HC (2004) Effect of toothwhitening strips and films on changes in color and surface roughness of resin composites. Clin Oral Investig 8(3): 118-122.

- Cao L, Huang L, Wu M, Hua Wei, Shouliang Zhao (2015) Effects of cold light bleaching on the color stability of composite resins. Int J Clin Exp Med 8(6): 8968-8976.

- Farah RI, Elwi H (2014) Spectrophotometric evaluation of color changes of bleach-shade resin-based composites after staining and bleaching. J Contemp Dent Pract 15: 587-594.

- Villalta P, Lu H, Okte Z, Garcia Godoy F, Powers JM (2006) Effects of staining and bleaching on color change of dental composite resins. J Prosthet Dent 95: 137-142.

- Xing W, Jiang T, Liang S, Sa Y, Wang Z, et al. (2014) Effect of in-office bleaching agents on the color changes of stained ceromers and direct composite resins. Acta Odontol Scand 72(8): 1032-1038.

- Mourouzis P, Koulaouzidou EA, Helvatjoglu Antoniades M (2013) Effect of inoffice bleaching agents on physical properties of dental composite resins. Quintessence Int 44(4): 295-302.

- De Munck J, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Poitevin A, Lambrechts P, et al. (2005) critical review of the durability of adhesion to tooth tissue: Methods and Results. J Dent Res 84(2): 118-132.

- Abdalla AI, Feilzer AJ (2008) Four-year water degradation of a total-etch and two self-etch adhesives bonded to dentin. J Dent 36(8): 611-617.

- Craig RG (1989) Restorative dental materials. 8th ed., CV Mosby Co., St. Louise.

- Ferracane JL (2001) Materials in dentistry ( Principles and Applications ). (2nd edn.), A Wolters Kluwer Co. Philadelphia.

- Joiner A (2004) Tooth colour: a review of the literature. J Dent 32(1): 3-12.

- Fontes, ST, Fernández MR, Moura CMD, Meireles SS (2009) Color stability of a nanofill composite: effect of different immersion media. J Appl Oral Sci 17(5): 388-3391.

- Lee YK, Lim BS, Kim CW (2003) Difference in polymerization color changes of dental resin composites by the measuring aperture size. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 66: 373-338.

- Abu Bakr N, Han L, Okamoto A, Iwaku M (2000) Color stability of compomer after immersion in various media. J Esthet Dent 12(5): 258- 263.

- Vichi A, Ferrari M, Davidson CL (2004) Color and opacity variations in three different resin-based composite products after water aging. Dent Mater 20(6): 530-534.

- Patel SB, Gordan VV, Barrett AA, Shen C (2004) The effect of surface finishing and storage solutions on the color stability of resin-based composites. J Am Dent Assoc 135(5): 587-594.

- Saraç D, Saraç YŞ, Külünk Ş, Ural Ç, Külünk T (2006) Farklı inorganik doldurucu içerikli kompozit rezinlerin renk sabitliği üzerine polisaj yöntemlerinin ve yüzey verniği uygulamanın etkisi GÜ Diş Hek Fak Derg 23(3): 169-175.

- Fay RM, Servos T, Powers JM (1999) Color of restorative materials after staining and bleaching. Oper Dent 24(5): 292-296.

- Bozkurt FÖ, Akalın T, Gözetici B, Genç G, Gözükarabağ H (2016) The Effect of Bleaching Treatment and Tea on Color Stability of Two Different Resin Composites. Aydın Dental Journal: 23-30.

- Rosentritt M, Lang R, Plein T, Behr M, Handel G (2005) Discoloration of restorative materials after bleaching application. Quintessence Int 36(1): 33-39.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...