Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4692

Editorial(ISSN: 2637-4692)

The Dental Service of the French Army in 1940 Volume 1 - Issue 1

Xavier Riaud*

- Doctor in Epistemology, National Academy of Dental Surgery, France

Received: January 06, 2018; Published: January 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Xavier Riaud, Doctor in Epistemology, National Academy of Dental Surgery, France

DOI: 10.32474/MADOHC.2018.01.000101

Brief Historical Summary

On December 1 1892, the Brouardel law was voted which gave legal status to dental surgeons. At that point, those who had followed appropriate studies delivered by the Faculty of Medicine were the only ones who could practise dental surgery [1]. Therefore, it was a profession in its infancy which enlisted during the war in 1939? On February 26 1916, a dental service was created in the infantry within the French army for the duration of the war. That of the Navy only started on March 1st 1916. After the Great War, only the Navy decided to dissolve its dental service for it did not have a satisfying organization to greet its patients. In 1934, a backup dental service was implemented once again. While they were made lieutenants in 1818, dentists could become captains after the law voted on December 19 1934 [2]. A few months later, dentists in the land army were attributed the same rank.

National Federation of Reserve Dental Surgeons (Federation Nationale Des Chirurgiens-Dentistes De Reserve - Fncdr)

In 1925, the first dental officers who returned to civil life assembled to form the Association of dentists of the land army, the navy and the air force from the Paris region during the 3rd Congress of medicine and military pharmacy. It was aiming at keeping the ties they built during the war and at helping each other to get back to normal life [3]. A two-year optional superior military training was created. Once students in dental surgery had passed it, it allowed them to accomplish the very last part of their military service as 2nd class military dentist which was a rank similar to that of second lieutenant. Then, they joined dental care garrisons, centres for edentulous patients or even centres for maxillofacial prosthodontics. In 1927, there were only eight of them. Those who had not passed their two-year optional superior military training were only able to join the nursing unit [4,5].

Thereafter, these associations asked the Minister of War and of National Defence the permission to open an advanced level training school for dental surgeons called EPOR. The central administration of the French Defence Health service (Direction centrale du Service de santé des armées -DCSSA), who was in charge of diversifying the health service’s branches, immediately supported the initiative which led to the opening of the first EPOR. This training school offered its first services during the monthly lectures of the Villemin military hospital on October 1926. From 1931, the initiative taken by Paris spread over the country and each military region could benefit from their own EPOR. Moreover, integrating this school soon became a prerequisite to get an upper grade [6].

In 1933, all those regional associations eventually gathered into a National federation of Reserve Dental surgeons which was notably later chaired by Pierre Budin who was one of the eleven chairmen of the federation and who received the Legion of Honour in 1920 for his bravery on the battlefield. This institution thoroughly devoted itself to the improvement of the dentists’ status. The DCSSA organized the dental surgeon’s training in order to get them ready for all sorts of duties: anaesthetists, surgical assistants, radiologists, first-aid workers, etc. It was Pierre Henry’s case who was mobilised in 1940 and who joined the surgical team of the Ancemont Hospital where he practised as anaesthetist. During the war, as he was demobilised, he practised in Rennes [7]. It was in this way that, in the Val-de-Grâce Hospital, the general practitioner Ginestet trained dental surgeons to specialties of maxillofacial surgery. The dentists were informed on various medical practices with respect to the damage caused by more modern weapons and which led to more complex and numerous maxillofacial injuries. All that work which was organised with the help of the DCSSA prepared the intervention of the dental surgeons’ corps in the event of future conflicts [4,5].

Active Dentists

The French Defence Health service which included the dental surgery service reshaped its organisation following the assessments which were carried out at the end of World War I. It decided to implement more mobile structures which aimed at following a regiment or a division or which were able to adapt to the new schemas of so-called movement wars. Therefore, mobile surgical groups, advanced hospitals, medical hospitals of evacuation and various health services appeared. Within each of these structures, one or two dentists were incorporated. Through Article 39, the law of April 1 1923 planned that dental students had to accomplish their military service in the health service as nurses if they had not finished their dental curriculum or as second class dental surgeons if they had graduated [7].

Mobilisation

World War II broke out on September 3 1939. Everybody mobilised in France. Reserve dental surgeons were called upon as lieutenants for the most of them on different strategic areas. They were either assigned in the sanitary formation of the divisions, in the surgical ambulances or in the front regiments. At the beginning of the war, they barely practised dentistry. They mainly served as assistants for specialised medical treatments. Only a few practised in the garrison dental surgeries or in those of hospitals. Indeed, with the growing mobilisation, the Health service created dental surgeries in each area settlements and in the most important garrisons. Thus, in the front, they intervened in aid stations to cure the wounded. In divisional areas, they collaborated with doctors and surgeons within mobile or advanced surgical groups. Finally, at the rear, they were employed by maxillofacial centres or by radiology services. At the beginning of the war, immediate interventions and first-aid treatment had priority and demanded a lot of efforts especially as the bombing victims were not only soldiers but also civilians. Those who had followed the teaching delivered by the EPOR were more easily assigned in surgical services [6].

(Delivered) Treatment

Curing the soldiers’ oral pathologies, soothing their pain and quickly making them operational was a primal objective. A man who is in pain does not fight right and immediately constitutes a threat for his comrades. Furthermore, a person with bad teething cannot chew properly which can lead to other general diseases. Seeing the soldiers and being among the troops also allowed the dental surgeons to deliver notions of oral hygiene. A schematic note was written for each soldier in order to keep track of his treatment and the head of the dental surgery also used to write reports on a daily basis. On them were written all the consultations and carried out interventions. Reconditioning oral cavities was systematically carried out before each military operation with a compulsory preliminary tartar removal which was the first hygienic approach. Numerous dental extractions were carried out. Each attribution of a prosthetic device had to be subjected to the approval of the head of the Regional Health Service through the main stomatologist’s intermediary.

Once the head of the dental surgery gave his approval the extractions were made before the making of a device. A month and a half later, the device could be made. On the contrary, if the making was refused, only extractions were made [6]. In each dental surgery, the staffs was made up of a department head who often was a stomatologist or a military dental surgeon and of military dental surgeons to assist him according to the needs decided by the main regional stomatologist. This department head was under the supervision of the chief doctor of the training to which he was linked such as the corps troops, the regimental infirmary, the military hospital, etc., while being under the main stomatologist’s command [7]. In 1940, continuing education was insured thanks to magazines such as “Odontologie” which ended its publication between June/ July 1944 and March/April 1945. In 1942, the publications spread for lack of promoting advertisement and because of the war, and eventually diminished until they did not get enough cover.

Stomatology Service

During World War II and after the French surrender which was signed in Rethondes on June 22 1940, numerous demobilised dental surgeons were called upon to treat soldiers who were wounded in the face. This was when maxillofacial surgery became extremely important in terms of medical care. It became a full-fledged specialty which benefited from new techniques and materials. Stomatology services existed along the secondary organisations such as the garrison dental surgeries which operated in each area settlements and in the most important garrisons. They were implemented at the beginning of the war.

There were two different articulations concerning the rear structures:

Inter-Regional Technical Services

The inter-regional centre of surgery and of maxillofacial prosthetics was independent from the regional service but was under the supervision of the chairman of the regional health service which it was a part of. A surgeon, head of department, was at its head and benefited from a stomatologist’s assistance who was leading the maxillofacial prosthetics service. As a team, they could rely on all the specialists and dental prosthetics technicians. In these inter-regional centres, they mainly treated damaged maxillary bones as well as those of the face and the neck thanks to this coeducational surgical and stomatological training. On the contrary, simpler maxillary fractures, that is to say those without a loss of substance, were treated in the regional stomatological centres. Likewise, simple edentulous patients were not accepted in surgical and stomatological centres. Centres for edentulous patients were implemented for the wounded that could be fitted with prosthesis. Each centre was specialised. The main objective was to quickly orientate the wounded.

Regional Technical Services

Only one stomatology service existed in a region. In the event of a big region, there could be more of them. Only one centre of dentures for edentulous patients worked to making the dentures of all the edentulous people who came in the dental surgeries of the local garrison. Those local stomatology and dental prosthetic services contained from 50 to 100 beds out of a total of around 10,000 and 20,000 beds for the entire medical sector. The odontostomatologic illnesses too important to be treated in the dental surgeries, the dental illnesses, simple maxillary or prosthetic fractures, and surgical extractions were operated there. The simple fitting of prosthesis on edentulous people was also carried out there. The management of regional centres was insured by the main local stomatologist. He had to keep a close watch on the stomatology and dental prosthetic centre, and dental surgeries. Here was his staff:

i. A dental prosthetist who was able to make a set of dentures per day, that is to say 30 dentures per month;

ii. A military dentist who was able to provide the same work than that of 4 out of 5 technicians.

An officer was in charge of the management of the equipment which included the maintenance and the stock according to the wants and needs. He also kept a log of which was fitted in the patients ‘mouths with the description of the device. This allowed justifying the price of each set of dentures. Finally, the local head could subsequently follow the activity of the centre for edentulous patients thanks to a monthly report [8]. The ability training of the military service of December 7 1938 for metropolitan troops included a calculation giving the soldier’s chewing coefficient. In case of a lack of needed dentures, the fitting was made possible only if the soldier’s chewing coefficient was lower to 25%. Therefore, each fully edentulous man could receive a full set of dentures and could be kept in the service (Figures 1-3).

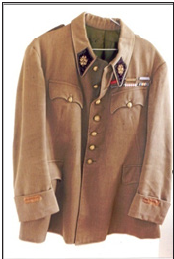

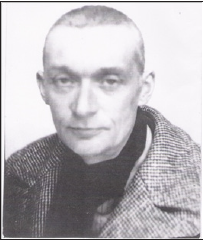

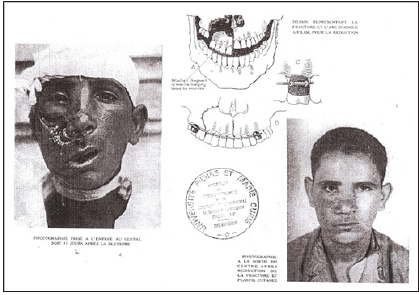

In case of maxillofacial emergency, the wounded soldier had to be driven to a maxillofacial centre from two to ten days after the injury. The quicker the treatment started the better were the chances of recovery. As for the repairing phase, it often needed transplants. The immobilisation of fractured bony edges was essential to be successful. The average period of the primary consolidation of transplants was of around two months but it was only around the fourth month that the transplants looked normal again. On November 11 1942, the German army invaded the free zone, France’s Southern part. A month later, Vichy’s “Armistice Army” was disbanded. Hence, the French Defence Health service no longer existed. Any medical support was entrusted to the British and mostly to the Americans during the conflict. In 1940, numerous demobilised dentists put up resistance, their dental surgeries often served as turntables for the exchange of information. Many of them were shot by the Gestapo [9]. Many others were deported and came back weakened from the camps (René Maheu)(Figure 4). Some others enlisted in the Free French Forces (Maurice Prochasson). Dental lieutenant’s uniform (purple velvet on the flat-topped French military cap, on the collar tips, the caduceus was visible on each collar tips and buttons), made between 1930 and 1935, worn in 1940, the khaki military cap was made from 1930. Before it was blue (Figure 5).

The braids were on the turn-ups during World War I. They were above the turn-ups from 1934/1935. Here, on the picture, they are on the turn-ups. The dental officer’s uniform was similar to that of the cavalry (executive order 1934)(Figures 6 & 7). Here, it was prior to 1934. Among the decorations, from left to right, the following ribbons are recognisable:

i. Knight of the Legion of Honour.

ii. 14-18 Cross of War (without mention in despatches).

iii. Combatant Cross (created following the law of June 28 1930).

iv. Impossible to identify, but given the order of wearing official French decorations, it could be the Allied Medal (or Victory Medal) created following the law of July 20 1922 and which was granted provided three successive months or not of presence between August 2 1914 and November 11 1918, to the soldiers belonging to the units enumerated by the ministerial instruction of October 7 1922, which is worn before distinction (Figures 8-11).

Figure 11: A soldier wounded in the face upon his arrival (left) and his departure (right) of the African centre (Converse J., Péri M. & Roche G. K. T., 1944).

v. Médaille commémorative française de la Grande Guerre

vi. The Insignia for the Military Wounded. The trousers have a command band which existed from 1830 [10-13].

References

- Morgenstern Henri (2009) French dentists in the 19th century, L’Harmattan (ed.), Medicine through the centuries Collection, Paris.

- Riaud Xavier (2009) World War I and stomatology, exceptional practitioners, L’Harmattan (ed.), Medicine through the centuries Collection, Paris.

- Jamin Sophie (2011) The French dentist during the Second World War, PhD in dental surgery, Rennes, France.

- Benmansour Alain (2002) History of the status of French military dentists. History of the French military dental surgeon’s status in The Surgeon- Dentist of France, No. 1063/64, pp. 34-39.

- Benmansour Alain (2002) Histoire du statut des chirurgiens-dentistes militaires français. History of the French military dental surgeon’s status in Le Chirurgien-Dentiste de France, 1065 : 52-56.

- Konieczny Bruno (1992) The dentist in the Health Service of the French Armies during modern wars, PhD in dental surgery, Rennes, Nantes, France.

- Jamin Sophie (2011) The French dentist during the Second World War, PhD in dental surgery, Rennes, France.

- Bourguignon Patrick (2004) The place of the dentist in the armed forces yesterday and today: the role of the reserve and the reservist. Dental surgeon’s rank within armed forces yesterday and today, PhD in dental surgery, Paris.

- Audigé Family (2005) Personal communication. Nantes, France.

- Riaud Xavier (2012) Personal collection, Saint Herblain, France.

- Pauchard Jean Michel (2012) Personal communication, Paris.

- Converse J, Péri M, Roche GKT (1994) Maxillofacial wounds : observations made during the 1942-1943 campaigns. African centre of reconstructive and maxillofacial surgery. Report of the interallied conference in Algiers, p. 1-2.

- Maheu Alain (2003) Personal communication, Saint Malo, France.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...