Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4692

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4692)

Pattern of Mandibular Fracture at Universal College of Medical Sciences (UCMS), Bhairahawa, Rupandehi, Nepal Volume 4 - Issue 2

Shashank Tripathi1*, Ravish Mishra1, Deepak Yadav1, Laxmi Kandel1, Bikash Pahari1 and Pradip Chhetri2

- 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Universal College of Medical Sciences, Nepal

- 2Department of Community Medicine, Universal College of Medical Sciences, Nepal

Received:December 04, 2019; Published: December 12, 2019

Corresponding author:Shashank Tripathi, Lecturer, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, UCMS College of Dental Surgery, Bhairahawa, Rupandehi, Nepal

DOI: 10.32474/MADOHC.2019.04.000181

Abstract

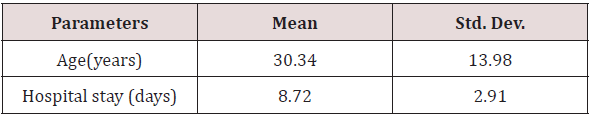

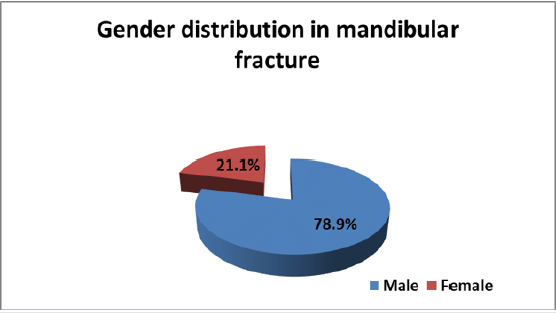

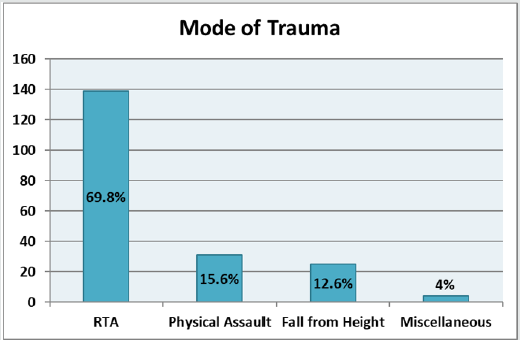

A descriptive retrospective study was carried out and evaluated the pattern of mandibular fractures in western region of Nepal at Universal College of Medical Sciences, Bhairahawa, Rupandehi. Among 498 cases of maxillofacial trauma registered between March 2014 to December 2018; 199 cases of mandibular fractures who were admitted and undergone conservative or surgical treatment were enrolled in the study. Parameters recorded were personal details of patients including age, sex, day and month of fracture, mode of trauma, alcohol abuse, site of mandibular fracture, treatment done, duration of hospital stay, and need for intensive care unit (ICU) stay. The selected group include 157 males (78.9%) and 42 females (21.1%). The mean age of patient was 30.34 ±13.98 years (age range, 3-77 years). The mode of trauma was from road traffic accident (69.8%) in majority of cases followed by physical assault (15.6%) and fall from height (12.6%). Majority of trauma for mandibular fracture were seen on Wednesday and Friday in the month of June followed by February and December. 27.1% of patients with mandibular fractures were under the influence of alcohol. Majority of patients (94%) were secondarily managed with open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) under general anesthesia followed by closed reduction under local anesthesia (3%) and circum-mandibular wiring under general anesthesia (3%). Circum-mandibular wiring was opted for patient who were in mixed dentition period. The mean duration of hospital stay was 8.72±2.91 days (range, 5-20 days) in which maximum hospital stays were with patients associated with craniofacial fracture and associated intracranial injury. Majority of patients (98%) were managed post operatively in general surgical wards whereas few patients (2%) were shifted to ICU from major operating room due to post-operative anesthetic complications. Para symphysis fracture were seen in majority of cases followed by angle and condyle respectively. The mechanism of injury correlates significantly with the anatomic location of fracture and knowledge of these associations should guide the surgeons for appropriate and timely management. Because RTAs are most frequent, good traffic sense needs to be imbibed and developed by the government as well as the public.

Keywords: Mandibular Fractures; Trauma; Pattern; RTAs

Introduction

Introduction

Mandible is one of the strongest and largest bone of face.

Though nasal bone is most common bone to get fractured; mandible

remains the second one [1,2]. Anatomically, mandible is ‘V’ or ‘horseshoe’

shaped which is most prominent at chin region and is mobile

part of our facial skeleton. Due to its shape, anatomic position and

being mobile, there is high chance of bone to get fractured. During

mandibular fracture, either single or multiple anatomic sites can be

involved simultaneously by the impact caused by various means.

The patterns of mandibular fracture differ significantly among

different study populations. Maxillofacial fractures results from

the variable modes of injury such as road traffic accidents (RTA),

interpersonal violence or physical assaults and fall from height

[3,4].

Once the patient is brought to emergency department with

complex maxillofacial trauma, patient management remains a

challenging task for oral and maxillofacial surgeons, demanding both

skills and a high level of expertise. It has been well documented that

mandibular fractures account for 36% to 59% of all maxillofacial

trauma [5-7]. Most of the reported prevalence of mandibular

fracture is due to a variety of contributing factors such as the

age and sex of patients, environment and socio-economic status

of the patient, alcohol or drug abuse as well as mode of trauma. The combination of more than one of these factors determines the

chance of a mandibular fracture in every single patient [8].

Despite of many published reports about the incidence and

pattern of mandibular fractures, there are limited literatures about

the specific type or pattern of mandibular fractures related to RTA in

developing and underdeveloped Asian countries. The present study

aimed to determine the age group and sex in which mandibular

fracture occurred most often; to determine the mode of trauma; to

know the pattern of mandible fracture which involve either single

or multiple sites; to know the possible contributory role of alcohol

and drug abuse; to report on the modalities of treatment provided

and number of days stayed in hospital or ICU.

Materials and Methods

The investigators designed and implemented a descriptive

retrospective study that was approved by the Institutional Review

Committee (IRC) of the Universal College of Medical Sciences,

Bhairahawa, Nepal (IRC number 045/19). Among 498 cases of

maxillofacial trauma registered between March 2014 to December

2018 at UCMS College of Dental Surgery, Bhairahawa, Rupandehi,

Nepal; 199 cases of mandibular fractures who were admitted and

undergone conservative or surgical treatment were enrolled in

the study. Parameters recorded were personal details of patients

including age, sex, day and month of fracture, mode of trauma,

alcohol abuse, site of mandibular fracture, treatment done, duration

of hospital stay, and need for intensive care unit (ICU) stay. All

maxillofacial injuries excluding mandibular fractures and patients

with incomplete medical record information were not included in

the study.

Data were entered in Microsoft Excel 2007 and analyzed by

means of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 18.0 for

Windows, SPSS Inc.). For descriptive statistics; percentage, mean,

range and standard deviation were calculated.

Results

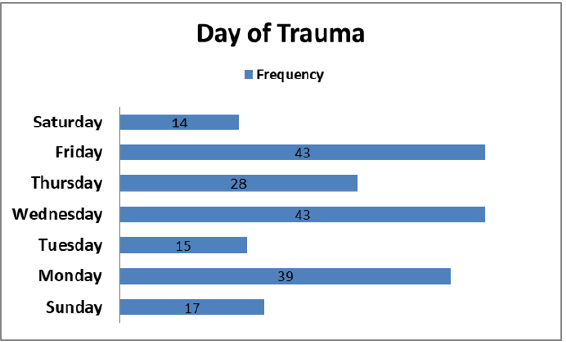

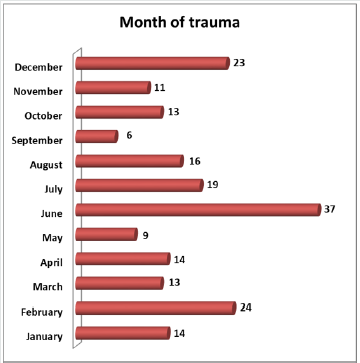

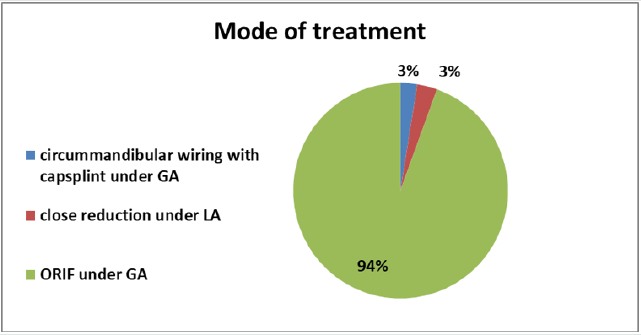

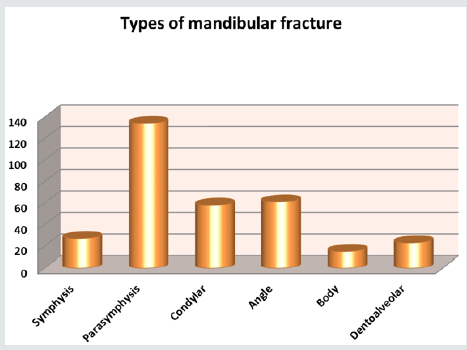

A total of 199 cases of mandibular fracture with complete medical records admitted and managed with stipulated period were included in the present study. The selected group include 157 males (78.9%) and 42 females (21.1%) as shown in Figure 1. The mean age of patient was 30.34±13.98 years (age range, 3-77 years) as shown in Table 1. The mode of trauma was from road traffic accident (69.8%) in majority of cases followed by physical assault (15.6%) and fall from height (12.6%) as shown in Figure 2. Majority of trauma for mandibular fracture were seen on Wednesday and Friday in the month of June followed by February and December as shown in Figure 3 & 4. 27.1% of patients with mandibular fractures were under the influence of alcohol as shown in Figure 5. Majority of patients (94%) were secondarily managed with open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) under general anesthesia followed by closed reduction under local anesthesia (3%) and circummandibular wiring under general anesthesia (3%) as shown in Figure 6. Circum-mandibular wiring was opted for patient who were in mixed dentition period. The mean duration of hospital stay was 8.72±2.91 days (range, 5-20 days) in which maximum hospital stays were with patients associated with craniofacial fracture as shown in Table 1. Majority of patients (98%) were managed post operatively in general surgical wards whereas few patients (2%) were shifted to ICU from major operating room due to postoperative anesthetic complications as shown in Figure 7. Para symphysis fracture were seen in majority of cases followed by angle and condyle respectively as shown in Figure 8. Body of mandible fracture were least fractured.

Discussion

The present study comprised of complete medical records

within stipulated time period of patients (n=199) aged 3 to 77

years with mandibular fractures attending Department of Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery, UCMS College of Dental Surgery, Bhairahawa

which is the only tertiary centre in western region of Nepal. Various

studies had been reported worldwide regarding the prevalence

and pattern of mandibular. The result of present study coincides

with the study done previously irrespective of age and sex [1-11].

In present study, the mean age of patients in years is 30.34±13.98

[1,2,4,5,8-10].

Most of the patients fall between age group of 21-35 years.

RTA (69.8%) being the commonest mode of trauma in mandibular

fracture followed by physical assault and fall from height. Most

common reasons for this may be due to the low socioeconomic

status of people leading to use of high numbers of two-wheelers

like bicycles, motorbikes, etc.; lack of awareness in using safety

measures in the form of helmets; use of alcohol while driving,

poor road condition and hilly areas. Males were predominant than

females in the present study. 78.9% of males were involved and the

reason behind this may be due to male dominant and dependent

society.

In the present study, Wednesday and Friday were the most

common days where patients were admitted with mandibular

fracture. Friday is the weekend for people in Nepal and Wednesday

is the mid of week where people try to engage themselves in

social gathering. In addition, alcohol is very easily available and

commonly used in such occasion. So, the chance of increase in RTA

and interpersonal violence under the influence of alcohol plays a

significant role. Month wise distribution shows higher incidence of

mandibular fracture in the month of June in the present study. In

Nepal, June is the month when there is maximum rainfall due to

which the condition of road is worsened and become slippery.

Para symphysis fracture was the most commonly observed

mandibular fracture in the present study followed by angle fracture

and condylar fracture which coincides with the study done by

Vetter et al. [10] According to Dingman and Natvig classification

of mandibular fractures, the anatomic pattern shows the incidence

of angle involvement of 36.32%, followed by the body (21.23%)

and the symphysis (17.81%) which is in coherent with the study

done by [11] Olson et al. [12], Allan et al. [13] and Hill et al. [14]

In contrast, study done by Hall and Ofodile [15] showed body

has the highest incidence of fractures, followed by the angle. This

variability in individual site fracture distribution shows that the

pattern is always multifactorial and the strongest variable with a

positive association is trauma via altercation.

Most of patients (94%) reported with mandibular fractures

have been treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF)

under general anesthesia. Patients in mixed dentition periods

were managed with circum mandibular wiring (CMW) to avoid

injury to developing permanent tooth buds. Only few patients who

could not afford treatment charge were successfully managed with

maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) with different means wiring

techniques like use of Erich’s arch bar, Ivy eyelet wiring, etc.

In the present study, the mean duration of hospital stays in

patients with mandibular fracture is found to be 8.72±2.91 days.

Prolonged hospital stays were for polytrauma patients with

associated limb fractures, concurrent intracranial injury, chest

injury, etc. Very few patients (2%) needed intensive care unit (ICU)

for associated intracranial injury along with maxillofacial fractures.

Conclusion

Nepal is one of the least developed country and high number of maxillofacial injuries have been reported in which most of them have been attributed to RTAs. The incidence of maxillofacial injuries can be drastically reduced by strict enforcement of traffic rules set by Nepal government. Strict use of safety measures during driving like proper use of seat belt, helmet and no use of alcohol help to reduce higher incidence of maxillofacial injuries. The etiology is closely associated with the anatomic location of mandibular fractures. The diagnosis, pattern of fractures, and their management should be associated with a concern for medico-legal purposes.

References

- Adebayo ET, Ajike OS, Adekeye EO (2003) Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Kaduna, Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg41(6):396-400.

- Deogratius BK, Isaac MM, Farrid S (2006) Epidemiology and management of maxillofacial fractures treated at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1998-2003. Int Dent J56(3):131-134.

- Scherer M, Sullivan WG, Smith DJ, Phillips LG, Robson MC(1989) An analysis of 1423 facial fractures in 788 patients at an urban trauma center. J Trauma 29(3):388-390.

- Thorn JJ, Mogeltoft M, Hansen PK (1986) Incidence and aetiological pattern of jaw fractures in Greenland.Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg15(4):372-379.

- Brook IM, Wood N (1983) Aetiology and incidence of facial fractures in adults. Int J Oral Surg 12(5):293-298.

- Ellis E 3rd, Moos KF, el-Attar A (1985) Ten years of mandibular fractures: an analysis of 2137 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol59(2):120-129.

- van Hoof RF, Merkx CA, Stekelenbrug EC (1977) The different patterns of fractures of the facial skeleton in four European countries. Int J Oral Surg6(1):3-11.

- Sojot AJ, Meisami T, Sandor GK, Clokie CM (2001) The epidemiology of mandibular fractures treated at the Toronto general hospital: A review of 246 cases. J Can Dent Assoc 67(11): 640-644.

- AdhikariR, KarmacharyaA, MallaN(2012)Pattern of mandibular fractures in western region of Nepal. Nepal Journal of Medical Sciences1(1): 45-48.

- Vetter JD, Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Smith DG (1991) Facial fractures occurring in a medium-sized metropolitan area: recent trends. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20(4):214-216.

- Dingman RO, Natvig P (1964) Surgery of facial fractures. BJS Society, Saunders, Philadelphia,PA, USA

- Olson RA, Fonseca RJ, Zeitler DL, Osbon DB (1982) Fractures of the mandible: a review of 580 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40(1):23-28.

- Allan BP, Daly CG (1990) Fractures of the mandible. A 35-year retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 19(5):268-271.

- Hill CM, Burford K, Martin A, Thomas DW (1998) A one-year review of maxillofacial sports injuries treated at an accident and emergency department. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 36(1):44-47.

- Hall SC, Ofodile FA (1991) Mandibular fractures in an American inner city: the harlem hospital center experience. J Natl Med Assoc 83(5):421-423.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...