Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4692

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4692)

Active Participation in Oral Health Education Improves Knowledge Among Children 3-5 Years of Age Volume 5 - Issue 3

Jayapriyaa Shanmugham1*, Cherilyn Sheets2 and Chester Douglass3

- 1Director of Research and Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Boston University, USA

- 2Co-Executive Director, Newport Coast Oral Facial Institute (NCOFI), USA

- 3Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, USA

Received: April 13, 2022; Published: April 21, 2022

Corresponding author: Jayapriyaa Shanmugham, Director of Research and Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Boston University, USA

DOI: 10.32474/MADOHC.2022.05.000212

Abstract

Objectives: This study evaluates the effectiveness of active participation on improving oral health knowledge among preschool children aged 3-5 years, using age-appropriate materials and multiple learning modalities.

Methods: Children aged 3-5 years were randomly assigned to either the test group, where children actively participated in oral health education (provided in English and Spanish), or the control group, where children viewed videos not related to oral health. Two educational sessions were used as part of the training: Lesson 1 focused on educating children about healthy versus unhealthy foods (n = 136); and Lesson 2 focused on oral hygiene habits (n = 132). Blinded post- testing was conducted and oral health knowledge before and after the education was evaluated to analyze the effectiveness of active participation.

Results: The test groups (English and Spanish taught) scored significantly higher on the post-test than the control groups. The knowledge of sticky foods and reasons for foods being sticky (p<0.0001), and the awareness on maintaining oral hygiene (p<0.0001) was significantly higher among the children in the test groups following the oral health education. When using a song to encourage children to participate and sing along to understand brushing methods, both English and Spanish test groups significantly improved in the post-test (p<0.0001).

Conclusion: The findings in our study suggest that the use of interactive child-friendly tools combined with multiple learning modalities (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and manipulative) among 3-5 years old preschool children can significantly improve their oral health knowledge.

Keywords: Oral Health Education; Active Learning; Learning Styles; Preschool Children; Oral Health Knowledge

Abbrevations: NCHS: National Center for Health Statistics; US: United States; ECC: Early Childhood Caries; ICDC: Inglewood Child Development Center; TFI: Tooth Fairy Island; AAPD: American Association of Pediatric Dentistry; AAP: American Association of Pediatrics

Introduction

Dental caries continues to be the most common chronic oral disease among children affecting not only their systemic health, but also their school performance and outdoor activities, and causing a financial burden for the families [1-4]. According to the last published report by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS 2018) the prevalence of total dental caries among children aged 2-5 years in the United States (US) was 21.4% [5]. While the prevalence of dental caries is higher among older children (50.5% for 6-11 years and 53.8 for 12-19 years), Early Childhood Caries (ECC), a severe form of dental caries is most prevalent among infants, toddlers and preschool children often requiring extensive dental treatment under general anesthesia [5-10]. Oral health education programs can be effective in improving oral health and in adopting healthy behaviors [11-13]. School-based oral health promotion programs are being used globally to improve the knowledge and attitude towards better oral health [12,14-16]. Studies among children six years and older have highlighted the benefits of incorporating oral health education in primary and middle schools [11,17-22]. In a recent systematic review of 31 published articles on schoolbased oral health promotion programs, overall, positive benefits were observed and most of the studies were among children older than 6 years and seven studies were among children in preschool [23]. Among the studies included in that review, it is unclear if oral health education by itself lead to improved knowledge or if it was the combination of oral health education with supervised tooth brushing, use of fluoridated toothpaste and the involvement of caregivers. Among children younger than 6 years improved knowledge following oral health education using age-appropriate materials was observed in few studies where shows and games helped retain oral health information better than the traditional didactic approach [24,25].

Additionally, filmed modeling and role playing where children actively participated were found to be more effective in delivering oral health education training in studies reported as early as the 70s [26,27] and in recent research (25, 28), and was also found to increase cooperation of children during dental treatment [28]. Learning styles are key when designing health education programs for children. Three main learning styles: visual (through sight), auditory (through hearing) and kinesthetic (through moving and touching) have been successfully used in early education programs [29]. Active learning, which employs exploration and interaction using a combination of these learning styles has been correlated with academic success among young children [30,31]. Currently, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of oral health education programs that use these modalities [24,32]. However, improved oral health knowledge and oral hygiene habits have been reported among studies that delivered oral health education through involvement of children in games and shows [24] or through drama and role-playing [33] thus highlighting the benefits of active participation that include visual, auditory and kinesthetic experiences. Typically, dental practitioners rely on parents to communicate the importance of oral health to young children [34- 36]. However, parents’ oral health literacy and beliefs may impact the oral health knowledge among children [35]. Therefore, in addition to improving parents’ oral health knowledge there is a vital need for effective oral health education training for young children to instill the importance of good oral health in early childhood given the early development of oral health problems [37]. In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of using age-appropriate methods and active participation in oral health education among young children aged 3-5 years.

Methods

Study Population

To evaluate the effectiveness of active participation in oral health education this study included 3-5 year old children enrolled in the Head Start program at the Inglewood Child Development Center (ICDC) in Inglewood, California [38]. This Head Start program included a total of 247 English and Spanish students from low-income families. Parents’ consent was obtained through permission slips prior to the oral health education sessions. Only children with signed permission slips were included in the study.

Study Design

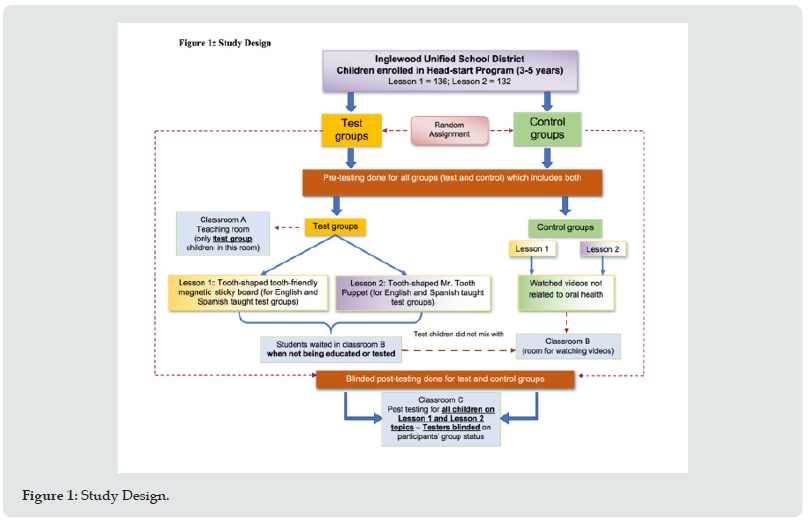

In this study, children were randomly assigned to either the test group where participants received the oral health education in two lessons (Lesson 1 and Lesson 2) or to the control group where no oral health education was provided (Figure 1). Both groups included children who were taught in English and Spanish. Prior to the oral health education training children in both groups were tested on their oral health knowledge. Following this the oral health education training was provided to the children in the test group. The children in the control group were in a separate room and watched videos not related to oral health. Four weeks after the oral health education training the oral health knowledge level was evaluated by testers who were blinded to the participants group assignments. Pre- and post-testing were conducted before and after the oral health training for all children with oral health knowledge as the primary outcome. The level of knowledge was compared between pre- and post-testing for both the test and control groups.

Study Participants

A total of 224 children (both English and Spanish speaking) registered for this study however not everyone participated due to absenteeism, moving or vacations. The children were divided into English or Spanish speaking groups based upon their teacher’s assessment of their language skills. A total of 136 children participated in Lesson 1 (English = 81; Spanish = 55) and 132 children participated in Lesson 2 (English = 77; Spanish = 55) (Table 1). For both language groups and for both lessons, children were randomly assigned to either the test or the control group (Figure 1).

Oral Health Education

The oral health education training in the test group included two main lessons (Lessons 1 and 2) using multiple modalities for learning (manipulative objects, visual stimulants, music and active movement). The characters and content used in the lessons were developed by expert educators at Tooth fairy Island (TFI), LLC, Irvine, California [38].

Lesson 1

Lesson 1 focused on educating children on healthy non-sticky versus unhealthy sticky foods using a tooth shaped Magnetic Sticky Board and hand-held graphic objects representing different food items. Sugary snacks such as cookies and candies were magnetized and thus would stick to the board. These were referred to as “unhealthy sticky” foods. Other foods such as apples and strawberries were not magnetized and therefore did not stick to the board. These healthy foods were referred to as non-sticky “tooth friendly” foods. The learning modalities used in this lesson include visual and tactile (kinesthetic) learning using objects that the children manipulated.

Lesson 2

Lesson 2 focused on the importance of oral hygiene by using a colorful puppet “Mr. Tooth Puppet” who had three overlaying coats. Each of the puppet’s coats represented the three levels of debris that can accumulate on a tooth: (1) food debris, (2) plaque and (3) hard calculus. Discussions on how these can be removed were conducted. The learning modalities used in this lesson include visual, tactile, auditory and kinesthetic methods using manipulative objects.

Pre-Testing

All children were pre-tested individually for their baseline level of oral health knowledge following a pre-determined protocol in a separate testing room within screened off private areas. For Lesson 1, during pre-testing, the students were shown the food graphics that represented sticky or non-sticky foods. Each child was asked to separate them into foods that stick to the teeth and foods that do not. They were also asked about reasons for why certain foods stuck to teeth. During pre-testing before the oral health education, the children were not allowed to test their choices on the board. Pre-testing for Lesson 2 involved a set of questions asking each child when and how they cleaned their teeth and when they needed to see a dentist.

Teaching Day

On teaching day, groups of children were escorted to a building with three adjoining classrooms. Classroom A was for teaching the oral health lessons, Classroom B was used as a waiting room and Classroom C was for post testing. The test group students were taken in small groups to Classroom A and taught the lessons using interactive participation. In lesson 1, the children were given the opportunity to use the Magnetic Sticky Board to differentiate between sticky unhealthy and non-sticky tooth friendly foods. Lesson 2 followed a week later where the children used Mr. Tooth Puppet with his three overlaying coats to understand the importance of removing (1) food, (2) plaque and (3) calculus to maintain good oral hygiene. Also, in lesson 2 the children learned brushing methods through active participation in singing.

Post-Testing

Post-testing was conducted for both lessons four weeks after the completion of the oral health education training. As the two lessons were taught in English and Spanish, each child was post tested in the same language in which the lessons were taught. To avoid bias, the teachers of the Spanish group, though bilingual, were not involved in teaching the English group. Teachers who taught lessons in Classroom A were not involved in the post testing in Classroom C. The testers in Classroom C had no knowledge of which students were educated in Classroom A (blinded post-testing). Post-testing for the children in the control group in both lessons was conducted randomly after these children watched videos not related to oral health. (See Appendix for more details on the lessons and testing).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and univariate analysis were conducted, and paired t-tests were used to evaluate the improvement between the preand post-test scores. Two sample t-test scores were compared between the test and control groups for each question, and between the English and Spanish taught groups. All analytic tests were conducted using STATA statistical software package. P- values <0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Lesson 1 included 136 children with 68 children in the test group and 68 children in the control group; and Lesson 2 included 132 children with 66 children in the test group and 66 children in the control group (Table 1). When evaluating children following Lesson 1 on identifying sticky foods, the post-training test scores for the test groups were significantly higher (p<0.0001) in both English and Spanish taught children (Table 2). Among the control groups, the children in the English group showed a significant improvement. In Lesson 1, when evaluating reasons for stickiness of certain foods the test group (both English and Spanish) scored significantly higher in the post-training evaluation (p<0.0001). Some improvement was observed in the Spanish taught children in the control group as well (Table 2). In Lesson 2, when evaluating children on the three levels of maintaining oral hygiene, the posttraining test scores among the test groups (both English and Spanish taught) were significantly higher (p<0.01) (Table 3). The English taught children showed no differences between the test and control groups when asked if it is necessary to see a dentist if they brush their teeth regularly, whereas the Spanish taught children showed significant differences between the test and control groups (p<0.0001). The post-test assessment for evaluation of tooth brushing knowledge was significantly higher among children who sang when learning to brush in both test groups and among children in the Spanish control group (data not shown).

Table 2:Lesson 1 – Mean differences (pre- versus post and test versus control) among children in both English and Spanish taught groups.

Table 3:Lesson 2 – Mean differences (pre- versus post and test versus control) among children in both English and Spanish taught groups.

aSD – Standard Deviation; bStatistically significant p-values <0.05

Discussion

The use of interactive oral health education program combined with multiple learning pathways (visual, auditory and kinesthetic) and active participation by children can be effective in improving oral health knowledge among 3-5-year-old preschool children. In this study, the children in the test groups, both English and Spanish taught, scored better on most post-test questions than the control groups thus showing a significant improvement in oral health knowledge. Our findings also suggest that interactive learning such as singing along exercises improved active participation. Repetition of information during singing and moving (kinesthetic learning) in this age group (3-5 years) tended to be more effective in knowledge retention.

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) report that dental caries continues to be the most common chronic disease in children [39, 40] and impact children’s growth and well-being [41]. Dental caries is a preventable condition and despite advances such as fluoridated tap water and increased public awareness, the prevalence of ECC in children less than 6 years continues to rise [39]. One of the most effective ways to prevent or reverse the effects of dental caries is to reduce exposure to sugars/fermentable carbohydrates [39,40,42]. Apart from dietary counseling by dentists, oral health education in schools can aid in improving the knowledge and awareness of healthy and unhealthy foods among children. Children depend on parents for guidance on basic day to day oral hygiene maintenance. However, while it is helpful for parents to guide children, parents with low level of education, language barriers or lack of time due to their occupation may be unable to provide proper oral health guidance to their children [43]. Practicing healthy behaviors early in life can have a positive impact on children’s overall health. As dental caries can develop as early as the time of eruption of the first tooth (at 5 months), it is vital to help children to adopt healthy oral health habits [44]. Therefore, in addition to oral health promotion efforts by dental care providers and caregivers, incorporating oral health education in schools for children in the early years can aid in improving their awareness and may encourage healthy dietary and oral hygiene habits. In this study, the participating children (3-5 years) in the test group were enthusiastic learners and showed significant improvement in oral health knowledge through active participation in the oral health education lessons.

Systematic reviews on oral health education among children have reported contradictory findings which may be due to differences in study methods and inadequate sample size in some studies [11,30]. In studies among older children 7 years and above, improvements in oral health status have been reported, however, there is limited evidence on the effect of oral health education among preschool children [32,45-51]. In a recent review (2021), 7 of 31 studies were among preschool children with overall positive outcomes following oral health education [23]. In that review most of the studies among preschool children included a combination of oral health education with supervised tooth brushing and/or use of fluoridated toothpaste as well as oral health educational training for teachers and parents. Two of the seven studies utilized non- didactic approaches such as games, drama and role playing which were effective in improving the oral health knowledge and oral hygiene habits. Other earlier studies that used age-appropriate materials among preschool children reported an improvement in oral health [22,52], but this was not consistent [32]. In comparison, a significantly higher level of knowledge was observed in this study when using oral health trainings with age-appropriate materials and multiple learning modalities that allowed for active participation and learning among children aged 3-5 years old.

Active Participation and Learning Modalities

Theories on cognitive development suggest that children between the ages 2-7 years are in the ‘preoperational’ stage where children engage in symbolic or active play [53]. Currently, many preschool educational programs are based on theories where children learn through active interaction and exploration [29,30]. Children actively learn using three main learning styles that include visual, auditory and kinesthetic learning [29]. Visual learning is where pictures, charts, and graphic images are used to communicate information; auditory learning involves listening to music or stories; and in kinesthetic learning children learn through touch using manipulative objects and through active movement such as dancing or playing. Learning during early childhood differs from learning during adulthood as younger children learn most efficiently through hands-on learning and active interaction with their environment [54,55]. Similarly, in this study, the evidence clearly highlights that learning through active participation and interaction improves the knowledge among preschool children. The learning modalities used for oral health education can help in improving knowledge and attitude towards adopting good habits among young children [56,57]. Previous studies have demonstrated that interactive learning, active participation and the use of audio-visual aids can improve the oral health knowledge than traditional learning methods among older children [56,57]. This has also been demonstrated in other areas of health education [58]. There is limited evidence on the use of these modalities in oral health education among children younger than 5 years [25-27,51]. In this study, active participation and interaction, and the use of various learning modalities were used in improving children’s oral health knowledge and awareness. In Lesson 1, the use of visual and tactile (kinesthetic) methods and in lesson 2 the use of visual and kinesthetic methods significantly improved the level of knowledge.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this interventional study is the strong evidence on the effectiveness of using various modalities of active learning in significantly improving oral health knowledge among 3- 5-year-old preschool children. Given limited previous evidence on oral health education programs using active learning methods, this study contributes to the literature. Other strengths of this study include: 1) Random assignment to test and control groups, 2) Use of child friendly education materials; 3) Active participation to facilitate a memorable learning experience and 4) Blinded post-testing for an unbiased evaluation. There are limitations to the current study. Lower participation rate and small sample size within the sub-groups may be limitations but it did allow appropriate univariate analysis. Future studies with a larger sample size may facilitate more in-depth multivariate analysis with adjustment of potential confounders. Another limitation is the generalizability of the findings as this study included only low-income English and Spanish families. The authors are also aware that short term assessment of knowledge (four weeks after the training) may not be sufficient to evaluate retention of knowledge and the impact on oral health status in the participating children.

Evaluating behavioral changes are also not possible in short term studies. Also, young children (<6 years old) may rely on parents for guidance and assistance with tooth brushing and may not completely comprehend the importance of going to the dentist. However, in this study the training was designed in a way that is appropriate for the age group of 3-5 years and used learning modalities that are suitable for these young children. While knowledge may not translate to behavior changes, it is the foundation for encouraging healthy habits and bringing about awareness in young children may aid in developing an interest in early years to adopt healthy habits. Also, the combined effort of dental care providers, parents, and schools is essential to bring about a positive change in the health of the children through structured and age-appropriate oral health educational training. Overall, despite the limitations of the study the authors strongly believe that the results of this study highlight the importance of providing early oral health education to young children to promote healthy eating and oral hygiene habits.

Conclusion

Findings from this study provide evidence that using sensory stimulating learning aids, multiple learning pathways and direct active participation during oral health education improves knowledge retention among preschool children aged 3-5 years. Additional large randomized blinded studies of active participation and long-term assessment of knowledge, behavior changes and assessment of oral health status through clinical examinations need to be conducted in order to evaluate the effectiveness of early oral health education for very young children and to test the long-term retention of knowledge.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jan Nelson, B.A., M.S.Ed. (President) and Marty Styskal, B.A., M.S.Ed. (Curriculum Developer) at Tooth fairy Island, LLC, San Louis Obispo, California, for donating the materials and concepts for this study. We thank the testing faculty Nelson Styskal, Lisa Ainsworth, Patricia Pineda, Adriana Navass and Tara Bultema. We also thank the Inglewood Unified School District, Inglewood Child Development Center and The Children’s Dental Center of Greater Los Angeles for their collaboration in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to be declared. None of the authors have any financial association with Tooth fairy Island or any other publishers of oral health education materials.

Appendix

Detailed description of study methods

Oral health education

The two lessons taught in the oral health education training, Lesson 1 and Lesson 2, were developed by expert educators at Tooth fairy Island (TFI), LLC, Irvine, California, a renowned organization in developing and providing child centered, culturally sensitive oral health information, provided educational materials for this study (38). The lessons were taught in both English and Spanish. During pre- and post-testing, the testers in the study wore TFI aprons to identify themselves as the oral health educators. To ensure that the participating children were comfortable and at ease the TFI aprons were colorfully designed with large child-themed fabric pockets of dragons, trains, cats and fish. The aprons were also useful in identifying the testers during the study.

Lesson 1

Lesson 1 using a tooth shaped magnetic sticky board taught the children about healthy non-sticky and unhealthy sticky foods. This board sat on a tripod frame and was placed on a table. Sugary snacks with white processed sugar such as cookies and candies were magnetized and thus would stick to the board. These were referred to as sticky foods. Other foods containing natural sugar, such as apples and strawberries were not magnetized and did not stick to the board thus landing on the table. These were referred to as non-sticky “tooth friendly” foods. To make sure that the children understood the term “sticky” the teachers used a sticky tape to demonstrate that it can stick to their clothes or objects. Each child was then told that every time we eat food, some of the food sticks to our teeth, just like the tape and that some foods stick more easily than others.

Lesson 2

In Lesson 2, the puppet referred to as Mr. Tooth Puppet with his three overlaying coats was used to demonstrate the importance of oral hygiene and cleaning the teeth. Each of the puppet’s coats represented the three levels of debris that can accumulate on a tooth: (1) food debri, (2) plaque and (3) calculus. When presented to the children that Mr. Tooth Puppet had attended a birthday party and is now covered with frosting (the first blue coat) the children were asked, “How do we clean Mr. Tooth?” The children’s first response was to “brush him with a toothbrush”. After a guided interactive discussion, the group learned that when they do not have a toothbrush while at the birthday party, the best solutions are to use the tongue to remove as much food as possible, wipe the teeth with a napkin and/or swish vigorously with water and swallow. The educator then removed the first blue coat (food debris) on the puppet and the children could see the second yellow coat (plaque) on the puppet. Discussion followed about how this second coat of plaque could be removed by brushing. The brushing method and a song that emphasized the actions of brushing the tooth were then taught to the children. Hand and body motions were used to demonstrate and act out the words of the song, “back and forth, up and down, do some circles round and round.” After the song, the teacher started to remove the 2nd coat, but before completely removing it, she asked the children, “If you brush your teeth as we just demonstrated, every day/twice a day, do you need to see a dentist?” and “Yes” or “No” responses from the children were recorded. The teacher then removed the second coat and the children saw that there was still a third grey coat on Mr. Tooth Puppet. The next question was, “How can we get this coat off of Mr. Tooth Puppet? Through a guided discussion they learned that none of the things they have discovered, using the tongue, swishing water, wiping with a napkin, or brushing and flossing, will remove this coat. Only a dentist or hygienist can remove the third coat on the tooth. After an explanation of what happens in a dentist’s office, the last coat was removed revealing a happy and clean Mr. Tooth Puppet.

Pre-testing

For Lesson 1, during pre-testing, the students were shown the twelve food graphics to represent sticky and non-sticky foods respectively. Each child was asked to separate them into ones that stick to the teeth and ones that do not. They were also asked about reasons for why certain foods stuck to teeth. During pre-testing the children were not allowed to test their choices on the board. Pretesting for Lesson 2 involved a set of questions asking the child when and how they cleaned their teeth. Children were also asked if they needed to see a dentist if they brushed every day. On pretesting day, 6-8 students were taken at one time from their Head Start classrooms to a separate testing room (classroom A). Two teachers invited two students to separate screened off private areas and individually pre-tested each child. A third teacher engaged the remaining waiting children with Lego toys. After pre-testing the children returned to their respective classroom.

Teaching Day

On teaching day, the children in the test group were taught using lessons 1 and 2. Lesson 1 on Tooth Friendly Snacks, using the magnetic board and twelve food choices in graphic form was used to educate children on healthy and unhealthy snacks to provide a visual separation of cariogenic and non-cariogenic foods. The children were given the opportunity to use the Magnetic Sticky Board to differentiate between sticky unhealthy foods which stuck to the board and non-sticky tooth friendly foods which did not stick to the board. The educators also discussed the role of white processed sugar that makes foods sticky. Lesson 2 followed a week later and used Mr. Tooth Puppet with his three overlaying coats to demonstrate the importance of oral hygiene. In lesson 2 brushing methods were taught using a song that emphasized the actions of brushing. Hand and body motions were used to demonstrate and act out the words of the song.

Post-testing:

During post-testing, which occurred four weeks later, groups of 12-15 students were randomly taken from their Head Start Classrooms and escorted to a building with three adjoining classrooms. Classroom A was for teaching the oral health lessons, Classroom B was a central holding room for all students and Classroom C was for post testing. The test students were taken in groups of 3 to 6 students to Classroom A and taught an interactive participation lesson. The testers in Classroom C had no knowledge of which students were educated in Classroom A (blind posttesting). Both control and test students were engaged with toys and videos while waiting in Classroom B. The testers in classroom A were blinded to the group status of the children when they arrived for testing. During post-testing for Lesson 1 the children in the test group were presented with the 12 foods and were asked to separate them into ones that stick to the teeth and ones that do not. They were also asked about reasons for why certain foods stuck to teeth. The children then separated the foods into “tooth friendly” (not sticky) or “not tooth friendly” (sticky) snacks and then tested their theory by placing each food on the tooth shaped graphic to see if the food “stuck to the tooth” or not. The sticky foods remained attached to the tooth on the magnetic board; the non- sticky foods fell off the tooth and landed on the table, thus providing a visual separation of the cariogenic and non-cariogenic foods. After this activity, the educators discussed with the children the role of white processed sugar that makes foods sticky. In Lesson 2 during posttesting the children responded to questions on maintaining oral hygiene using Mr. Tooth Puppet and its three overlaying coats. The children were given the opportunity to play with Mr. Tooth Puppet while responding to questions. After the children were post tested, they were rewarded with a TFI character sticker and returned to their respective classroom. While waiting for their turn, the control group children watched videos that are not on oral health and when it was their turn for post-testing, they were randomly taken to classroom A for post-testing.

References

- Rockville MD (2000) Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health 28(9): 685-695.

- (2015) Dental health and hygiene for young children. American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Oliveira E, Narendran S, Williamson D (2000) Oral health knowledge, attitudes and preventive practices of third grade school children. Pediatric Dentistry 22(5): 395-400.

- Chou R, Cantor A, Zakher B, Mitchell J, Pappas M (2013) Preventing dental caries in children<5 years: Systematic review updating USPSTF recommendation. Pediatrics 132(2):332-350.

- Fleming E, Afful J (2018) Prevalence of total and untreated dental caries among youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief 307: 1-8.

- (2020) Statement on Early Childhood Caries: American Dental Association.

- Dye B, Vargas C (2010) Trends in Paediatric dental caries by poverty status in the United States. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 20: 132-143.

- Dye B, Xianfen L, Thornton-Evans G (2012) Oral health disparities as determined by selected healthy people 2020 oral health objectives for the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data Brief 104: 1-8.

- Bagramian R, Garcia Godoy F, Volpe A (2009) The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. American Journal of Dentistry 22(1): 3-8.

- Anil S, Anand P (2017) Early Childhood Caries: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Prevention. Frontiers in Pediatrics 18(5): 157.

- Gambhir R, Sohi R, Nanda T, Sawhney G, Setia S (2013) Impact of school based oral health education programmed in India: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 7(12):3107-10.

- Kay E, Locker D (1996) Is dental health education effective? A systematic review of current evidence. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 24(4): 231-235.

- Nakre P, Harikiran A (2013) Effectiveness of oral health education programs: A systematic review. Journal of International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry 3(2):103-115.

- Habbu S, Krishnappa P (2015) Effectiveness of oral health education in children - a systematic review of current evidence (2005-2011). International Dental Journal 65(2): 57-64.

- Potisomporn P, Sukarawan W, Sriarj W (2019) Improved oral health knowledge, attitudes, and plaque scores in Thai third-grade students: A randomized clinical trial. Oral Health and Preventive Dentistry 17(6):523-531.

- Nguyen V, Zaitsu T, Oshiro A, Tran T, Nguyen Y, et al. (2021) Impact of school- based oral health education on Vietnamese adolescents: A 6-month study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(5): 2715.

- Biesbrock A, Walters P, Bartizek R (2003) Initial impact of a National Dental Education Program on the oral health and dental knowledge of children. Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 4(2): 1-10.

- D'Cruz A, Aradhya S (2013) Impact of oral health education on oral hygiene knowledge, practices, plaque control and gingival health of 13- to 15-year-old children in Bangalore city. International Journal of Dental Hygiene 11: 126-133.

- Shenoy R, Sequeira P (2010) Effectiveness of a school dental education program in improving oral health knowledge and oral hygiene practices and status of 12- to 13-year-old school children. Indian Journal of Dental Research 21(2): 253-259.

- Vanobbergen J, Declerck D, Mwalili S, Martens L (2004) The effectiveness of a 6-year oral health education programme for primary school children. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 32(3): 173-82.

- Rong W, Bian J, Wang W, De Wang J (2003) Effectiveness of an oral health education and caries prevention program in kindergartens in China. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 31(6): 412-416.

- Grant J, Kotch J, Quinonez R, Kerr J, Roberts M (2010) Evaluation of knowledge, attitude and self-reported behaviors among 3-5 year old school children using an oral health and nutrition intervention. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry 35(1): 59-64.

- Bramantoro T, Santoso C, Hariyani N, Setyowati D, Zulfiana A, Nor N, et al. (2021) Effectiveness of the school-based oral health promotion programmed from preschool to high school: A systematic review 16(8): e0256007.

- Makuch A, Reschke K (2001) Playing games in promoting childhood dental health. Patient Education and Counseling 43(1): 105-110.

- Malik A, Sabharwal S, Kumar A, Samant P, Singh A, et al. (2017) Implementation of game-based oral health education vs conventional oral health education on children's oral health- related knowledge and oral hygiene status. International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry 10(3): 257-260.

- Melamed BG (1977) Preparing children for dental treatment: effects of film modeling. Proceedings of the First National Conference on Behavioral Dentistry; West Virginia University, Virginia, USA.

- Melamed BG (1975) Reduction of fear-related dental management problems with use of filmed modeling. The Journal of the American Dental Association 90(4): 822-826.

- Paryab M, Arab Z (2014) The effect of filmed modeling on the anxious and cooperative behavior of 4-6 years old children during dental treatment: A randomized clinical trial study. Dental Research Journal 11(4): 502-507.

- Balat G (2014) Analyzing the relationship between learning styles and basic concept knowledge level of kindergarten children. Educational Research Review 9(24): 1400-1405.

- Hohmann M, Weikart D (1995) Educating young children: Active learning practices for preschool and child care programs. In: Educating young children, a curriculum guide from High/Scope Educational Research Foundation [Internet]. Ypsilanti, Michigan, High/Scope Press, USA.

- Buchanan H, McDermott P, Schaefer B (1998) Agreement among classroom observers of children's stylistic learning behaviors. Psychology in the Schools 35(4): 355-362.

- Agouropoulos A, Twetman S, Pandis N, Kavvadia K, et al. (2014) Caries- preventive effectiveness of fluoride varnish as adjunct to oral health promotion and supervised tooth brushing in preschool children: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of Dentistry 42(10): 1277-1283.

- John B, Asokan S, Shankar S (2013) Evaluation of different health education interventions among preschoolers: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry 31(2): 96-99.

- Bridges S, Parthasarathy D, Wong H, Yiu C, Au T, et al. (2014) The relationship between caregiver functional oral health literacy and child oral health status. Patient Education and Counseling 94(3): 411-416.

- Kanellis M, Logan H, Jakobsen J (1997) Changes in maternal attitude toward baby bottle dental decay. Pediatric Dentistry 19(1): 56-60.

- Miller E, Lee J, DeWalt D (2010) Impact of caregiver literacy on children's oral health status. Pediatrics 126(1): 107-114.

- (2011) Inglewood Child Development Center, Inglewood Unified School District.

- (2020) Tooth Fairy Island, LLC Irvine, CA2020.

- Policy on dietary recommendations for infants, children and adolescents. American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), 2016-2017.

- (2011) The Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry: American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD).

- (2016) America's Children in Brief: Key National Indicators of Well-Being. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, Washington, DC, USA.

- (2014) Policy Statement: Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD).

- Gold J, Tomar S (2018) Interdisciplinary community-based oral health program for women and children at WIC. Maternal and Child Health Journal 22(11):1617-1623.

- (2003) Dental Growth and Development. American Association of Pediatric Dentistry.

- Anaise JZ, Zilkah E (1976) Effectiveness of a dental education program on oral cleanliness of schoolchildren in Israel. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 4(5): 186-189.

- Hartono SW, Lambri SE, van Palenstein Helderman WH (2002) Effectiveness of primary school-based oral health education in West Java, Indonesia. International Dent Journal 52(3): 137-143.

- Hochstetter AS, Lombardo MJ, D Eramo L, Piovano S, Bordoni N (2007) Effectiveness of a preventive educational programme on the oral health of preschool children. Promotion and Education 14(3): 155-158.

- Petersen PE, Peng B, Tai B, Bian Z, Fan M (2004) Effect of a school-based oral health education programme in Wuhan City, Peoples Republic of China. International Dental Journal 54(1): 33-41.

- Rose C, Rogers E, Kleinman P, Shory N, Meehan J, et al. (1979) An assessment of the Alabama Smile Keeper school dental health education program. Journal of American Dental Association 98(1): 51-54.

- Wierzbicka M, Petersen PE, Szatko F, Dybizbanska E, Kalo I (2002) Changing oral health status and oral health behavior of schoolchildren in Poland. Community Dental Health 19(4):243-50.

- Cruz A (2020) Raising awareness of good oral health to preschool children/Good oral health; beautiful smiles. Capstone Projects and master’s Theses pp. 769.

- Gorelick M, Clark E (1985) Effects of a nutrition program on knowledge of preschool children. Journal of Nutrition Education 17(3): 88-92.

- Huitt W, Hummel J (2003) Piaget's theory of cognitive development. Valdosta, GA: Educational Psychology Interactive.

- Barbieru I (2016) Key concepts in the pedagogy of John Dewey. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology. VI (LXVIII)(1B): 71-74.

- Williams M (2017) John Dewey in the 21st Century. Journal of Inquiry and Action in Education 9(1): 91-102.

- Singh H, Kabbarah A, Singhal S (2017) Evidence Brief: Behavioural impacts of school-based oral health education among children. Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario).

- Dumitrascu L, Dumitrache M, Sfeatcu L, Podoleanu E (2011) Oral health education of school children through audio-visual methods. E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB).

- Dudley D, Cotton W, Peralta L (2015) Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 12(28).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...