Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4749

Opinion(ISSN: 2637-4749)

Is the Water Really Safe to Drink? A Potential Threat of Cyanotoxin Poisoning of Livestock by Water Supplies to Facilities Cyanotoxin Poisoning of Livestock in Facilities Volume 3 - Issue 2

Jian Yuan1,2*

- 1Department of Veterinary Diagnostic and Production Animal Medicine, Iowa State University, USA

- 2Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Iowa State University, USA

Received: January 14, 2020; Published: January 21, 2020

Corresponding author: Jian Yuan, Department of Veterinary Diagnostic and Production Animal Medicine, Iowa State University, USA

DOI: 10.32474/CDVS.2020.03.000160

Abstract

Freshwater toxic cyanobacteria can produce potent cyanotoxins which are detrimental and lethal to animals. Water from farm ponds contaminated by cyanotoxins can carry the toxins to nearby livestock facilities, posing a threat of animal poisoning when toxins reach a dangerous level. Therefore, fast and precise means should be conducted to reveal the existence and levels of cyanotoxins and toxic cyanobacteria to find out such threats in a timely fashion.

Keywords: Toxic cyanobacteria; cyanotoxins; farm ponds; livestock; facilities

Abbreviations: HAB: Harmful Algal Bloom; ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay; HPLC: High Performance Liquid Chromatography; MS: Mass Spectrometry; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction

Introduction

Cyanobacteria, colloquially called blue-green algae, are a group

of photoautotrophic prokaryotic microalgae which inhabit a variety

of environments on earth. Their ubiquity in global freshwater

bodies has made them important cosmopolitan organisms in

freshwater habitats. Being able to proliferate explosively under

appropriate ambient conditions, for example sufficient nitrogen

and/or phosphorus nutrients, cyanobacteria can easily become

dominant in inhabited ecosystems and form an ecological

phenomenon/disaster named HAB. An HAB can bring about many

deleterious impacts on local ecosystems such as hypoxia caused

by over consumption of oxygen by bacteria for degrading dead

cyanobacterial cells. What is even worse, some cyanobacteria can

produce potent cyanotoxins toxic to animals and humans, and the

toxins can be enriched to a dangerous level in an HAB, causing health

and sanitation problems [1,2]. Cyanotoxins contain a tremendous

number of species and are categorized by their toxicological

effects into hepatotoxin, neurotoxins, cytotoxin, etc. Microcystin,

anatoxin-a, and cylindrospermopsin are the most prevalent

representative toxins that fall into the three categories, respectively.

They can kill a poisoned animal in a very low dose (e.g, 3 ppb for a

nursery pig) [1]. As a secondary metabolite, these toxins are mostly

produced by cyanobacterial species in Microcystis, Anabaena, and

Cylindrospermopsis, respectively, although their production is also

found in other genera. The process of toxin production is well

profiled and regulated under a synthetic mechanism by a group

of enzymes that are translated from clustered toxin synthetase

genes [3-5]. Direct detection of cyanotoxins can be conducted using

ELISA, HPLC, and MS. These techniques are already characterized

with satisfactory specificities and sensitivities. Moreover, detection

of toxic cyanobacteria can be done as an alternative approach for

identifying toxicity. Because a toxic species actually has toxic strains

as well as non-toxic strains that share identical morphologies but

lack the toxin synthetase genes, traditional microscopic examination

cannot fulfill the purpose of accurate recognition of toxicity. As a

result, molecular methods targeting the existence of toxin genes is

an effective approach to find out the toxic cyanobacteria, of which

PCR is the most popular. While, intuitively, existence of genes doesn’t

equate to production of toxins as there is likely a “switching on/off”

mechanism of the genes (frankly, “toxigenic” is more accurate than

“toxic” per se), findings of good correlations for their existence as well as quantities suggest revelation of toxic cyanobacteria is an

excellent indicator of toxicity [6].

Microcystis and Anabaena exist across extensive latitudes, and

Cylindrospermopsis can be discovered in temperate zones despite

it was found in tropical zones. They grow in some waterbodies

which are also water sources for livestock. Although the water is

sometimes treated to remove possible contaminants, it is directly

transported to facilities for animals’ consumption, increasing the

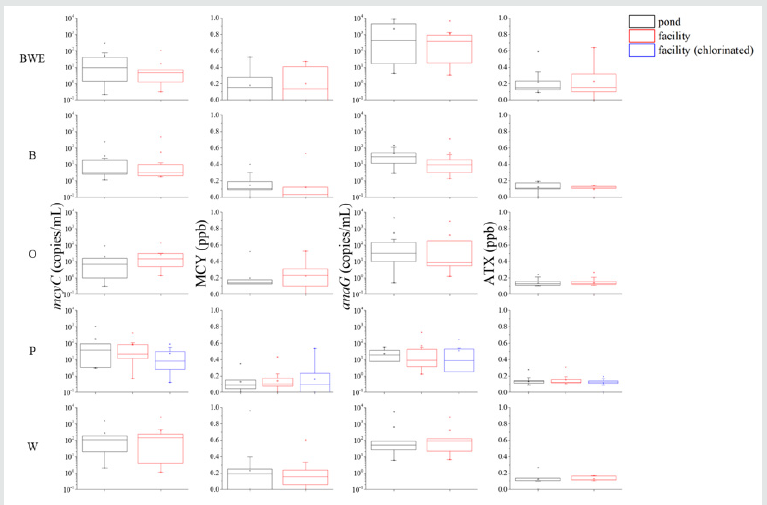

likelihood of cyanotoxin poisoning. In my recent study in five farm

ponds and five swine facilities served by these ponds as water

sources in the Midwestern United States, it was found that the

abundances of toxic Microcystis spp. and Anabaena spp., and levels

of microcystin and anatoxin-a had no significant differences (p >

0.05 by paired t-tests) in water between ponds and facilities with

a few chlorinated samples in one facility for detoxification (Figure

1). Although all the quantities were far below the warning levels for

an HAB or a toxicosis, chronical effects may occur on swine due to

accumulation of toxic cyanobacteria and/or toxins. More crucially,

swine can easily be poisoned once toxins are rapidly accumulated

in an unpredictable HAB event. Furthermore, the failure of

decontamination of cyanotoxins by chlorination suggests an option

of effective detoxification.

Figure 1: Abundances of toxic Microcystis spp. and Anabaena spp, and levels of microcystin and anatoxin-a in 105 water samples from five farm ponds and five swine facilities in the Midwestern United States. Toxic Microcystis spp. and Anabaena spp. are represented by one synthetase gene for microcystin and anatoxins-a (mcyC and anaG), respectively. MCY and ATX are abbreviations for microcystin and anatoxins-a, respectively. Ponds and facilities are indicated by BWE, B,O,P, and W. Black, red, and blue squares refer to pond water, facility unprocessed water, and chlorinated water, respectively..

Conclusion

In farm ponds as water resources to facilities lies a potential threat of livestock poisoning by cyanotoxins produced by toxic cyanobacteria. Therefore, accurate and prompt detection approaches for toxins and their producers are highly necessary. Nowadays, detection of toxic cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins is a component of routine water monitoring programs for large and important waterbodies like lakes and reservoirs. However, such a program doesn’t exist for small farm ponds that are prone to eutrophication (over enrichment of nutrients) causing HABs. As they are vital for livestock health as water sources, it is strongly suggested monitoring of toxic cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins should be set up in these farm ponds as a diagnostic or prewarning tool for veterinarians, producers, and stakeholders.

References

- Classen DM, Schwartz KJ, Madson D, Ensley SM (2017) Microcystin toxicosis in nursery pigs. Journal of Swine Health and Production 25(4): 198-205.

- J Swine He Pouria S, de Andrade A, Barbosa J, Cavalcanti RL, Barreto VTS, et al. (1998) Fatal microcystin intoxication in haemodialysis unit in Caruaru, Brazil. Lancet 352(9121):21-26.

- Pacheco AB, Guedes IS, Azevedo SM (2016) Is qPCR a reliable indicator of cyanotoxin risk in freshwater? Toxins 8(6): 172.

- Tillett D, Dittmann E, Erhard M, Dohren HV, Borner T, et al (2000) Structural organization of microcystin biosynthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806: an integrated peptide-polyketide synthetase system. Chem Biol7(10):753-64.

- Mejean A, Paci G, Gautier V, Ploux O (2014) Biosynthesis of anatoxin-a and analogues (anatoxins) in cyanobacteria. Toxicon 91:15-22.

- Mihali TK, Kellmann R, Muenchhoff J, Barrow KD, Neilan BA (2008) Characterization of the gene cluster responsible for cylindrospermopsin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol 74(3):716-722.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...