Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Research ArticleOpen Access

The Anti-Asian American Pacific Islander Bias Survey: Anti- Asian Bias Spectrum from Microaggressions to Violence Volume 4 - Issue 1

Elizabeth Ching*

Department of Occupational Therapy, Samuel Merritt University, USA

Received: July 7, 2022 Published: July 15, 2022

*Corresponding author: Elizabeth Ching, Department of Occupational Therapy, Samuel Merritt University, USA

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2022.04.000178

Abstract

Background: Anti-Asian bias is not a new phenomenon. The murders of eight victims at spas in Georgia with six of the victims being Asian women has caused a new generation to speak up about the discrimination that is directed toward those who identify as Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI).

Objectives: The brief Anti-Asian American Pacific Islander Bias Survey (AAAPIBS) was developed to view how discrimination shows up from microaggressions to violence on the spectrum of Anti-Asian bias.

Methodology: A convenience sample of occupational therapy practitioners and Asian American women in academia in the U.S. were given the survey.

Results: Anti-Asian discrimination occurs on a spectrum which has two major themes: Perpetual Foreigner and Model Minority. One new item emerged which was cultural appropriation from AAPI practices which are sources of cultural strengths and support, e.g. Mindfulness.

Implications: Anti-AAPI bias hinders the complete participation of AAPI Peoples in our society.

Keywords: Cultural appropriation; Envied Outgroup; Microaggressions; Model Minority; Perpetual Foreigner

Introduction

Anti-Asian bias is not a new phenomenon. The murders of eight victims at spas in Georgia with six of the victims being Asian women has caused a new generation to speak up about the discrimination that is directed toward those who identify as Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI). The brief Anti-Asian American Pacific Islander Bias Survey (AAAPIBS) was given to view how discrimination shows up from microaggressions to violence on the spectrum of Anti-Asian bias within a convenience sample of occupational therapy practitioners and Asian American women in academia in the U.S. This review sought to explore the prevalence of Anti-Asian bias as experienced from those who identify as Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI). There are generally two types of stereotypes for AAPI individuals: Model Minority vs. Perpetual Foreigner. Ways to buffer against Asian Hate are also discussed.

Model Minority

There is a range of Anti-Asian phobia which has risen during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Because of the “Envied Outgroup” (Akiba, 2020) status of Asians in the U.S., there are circumstances which are troubling especially since many of the Asians who have reported discrimination and bias during this time are children. There is a long history of K-12 schools neglecting the needs of Asian children due to the misperception of all Asian students academically performing well and also not having any behavioral issues. Asian children have been bullied by their peers from all racial categories without corresponding actions taken to alleviate the trauma (Akiba [1]). The stereotype of AAPI people as a successful monolithic group as a divider to keep other Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) down starts at an early age. Some students are perceived to have Science, Technology, Engineering, Math (STEM) success. Because health science students need to be strong in the math and science coursework [STEM+H(Health)], Williams, George-Jones, and Helb study of five different trials on racial phenotypes research design is applicable to how students of color may be perceived. Racial phenotypes or how one’s appearance is viewed as typical of one’s racial group with respect to Asian Americans and African Americans specifically with white students used for comparative purposes in STEM success. For those who were perceived to be more stereotypically East Asian, raters perceived them as stronger in Science and Mathematics as opposed to those within Asian groups who were not seen as stereotypically East Asian. For African Americans, those who appeared more stereotypically African American based on physical appearance of skin color, etc., raters scored them as having poor Science and Mathematics propensity. White students were perceived to have a good ability for STEM. Within group differences need more attention rather than a one-size-fits-all response to target inclusion of students of color in STEM or STEM+H. The bias is that East Asian individuals are automatically proficient in Science and Math, and there is a question on the survey which takes this stereotype into account.

Perpetual Foreigner

During the early days of the pandemic, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and “vicarious discrimination” (Lee & Waters [2]) were responses to anti-Asian bias. Mental and physical health were affected by anti-Asian racism (Cheng et al. [3]; Yang et al. [4]). Vicarious discrimination refers to individuals not being targeted themselves but seeing attacks or anti-Asian incidents on social media, for example. Anti-Chinese racism has a long history but before the pandemic can be traced most recently to SARS in 2003 were placing blame for a disease infection on one racial group should be noted (Misra et al. [5]). The stereotypes of Asians being reserved, diligent, and intellectual and not having good social skills are often utilized to not challenge White privilege and works to keep the “bamboo ceiling” (Atkin & Tran [6]) in place at predominantly White institutions (PWI). Asians are seen as worker bees rather than in positions of leadership and influence at PWIs (Atkin & Tran [6]).

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused burdens for everyone. Because of fear of contracting COVID-19 and lack of knowledge about the virus, participants of a survey regarding Anti-Asian sentiments scored higher for bias. In addition, participants who had a distrust of science, and were trusting in former President Trump also scored higher for bias (Dhahani & Franz [7]). Therefore, those who identify as Asian in the U.S. have an additional challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic to deal with Anti-Asian discrimination.

Support

Non-governmental organizations launched the STOP AAPI HATE tracker of COVID-19 related Anti-Asian violence and discrimination in March 2020. Asians with Asian Americans having the most mental disorders since the start of the pandemic compared to Whites has been demonstrated (Wu et al. [8]). In addition, “Minority Stress Theory” (Wu et al. [8]) is discussed in terms of racial trauma contributing to the mental health burdens of Asians in the U.S. Asians in the U.S. have had low rates of seeking support for mental health issues (Wang et al. [9]). Policy issues related to Asians and mental health must include attention to hate, violence, and discrimination experienced by AAPI individuals and groups (Wu et al. [8]; Akiba, [1]; Misra et al. [14]).

According to Murray-García, Harrell, García, and Gizzi, the focus of multicultural education for health professionals has often been on increasing cultural knowledge of the practitioners by extracting information from patients rather than on the crucial concept of the health professional being skilled at having a dialogue about race and racism (2014). The skilled dialogue on race and racism is integral to contributing to the health and wellness of the patient along with the development of a health care professional. The evidence from social psychology includes implicit bias, explicit bias, and aversive racism as key concepts to recognizing how to reduce health disparities. Knowledge of how one is perceived is key to resiliency (McConnell, [10]).

Being rooted to ones’s ethnic identity and knowing about stereotypes of one’s racial group can be protective to one’s mental health and build resilience in facing racial discrimination (Atkin & Tran, [4]; Kodama & Dugan, [11]). In terms of when K-12 schools open up and Asian children return, there are several recommendations. The first is to denounce Anti-Asian hate, remediate the stereotypes, and provide information for others to see the humanity of Asians who are not a monolithic group (Akiba, [1]).

Materials and Methods

The initial survey was to gather the responses from an anonymous 20-question survey from voluntary participants with a Qualtrics link on the www.asianot.org website. Participants were asked to voluntarily complete the 20-question survey if they racially identified as Asian American Pacific Islander to allow the data to be used for research purposes. The link was on the website during the Summer of 2021. The survey states that 5 to 10 minutes are required to answer questions and write additional optional comments. The instrument has a consent question to publish anonymous responses to the survey. The survey also has a “Trigger Warning” to denote those painful memories may arise and to seek one’s own personal support if needed after taking the survey. The instrument does state that the purpose is to use the data to discuss Anti-Asian bias as experienced by those who identify as Asian American Pacific Islanders. Because of a low response rate on the www.asianot.org website, the survey was also included as a learning strategy in the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education (NCORE) Webinar Series: It’s Complicated: Asian American Women in Academia in the Fall of 2021. The anonymous survey was optional and over 30 participants took the survey. At the time of the close of the survey on October 13, 2021, there were a total of 37 useable responses of those who identified as AAPI individuals. Qualtrics features were used for data distributions.

Results/Observations

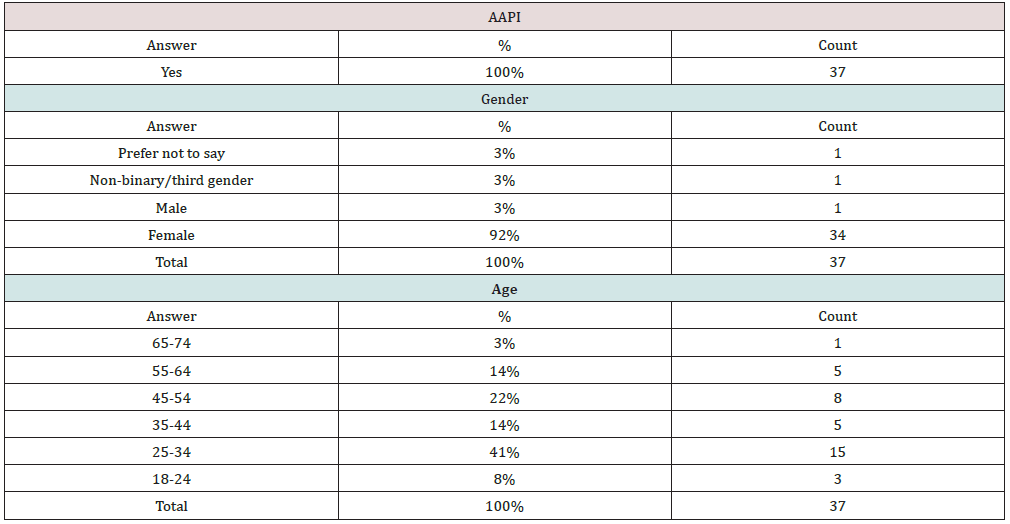

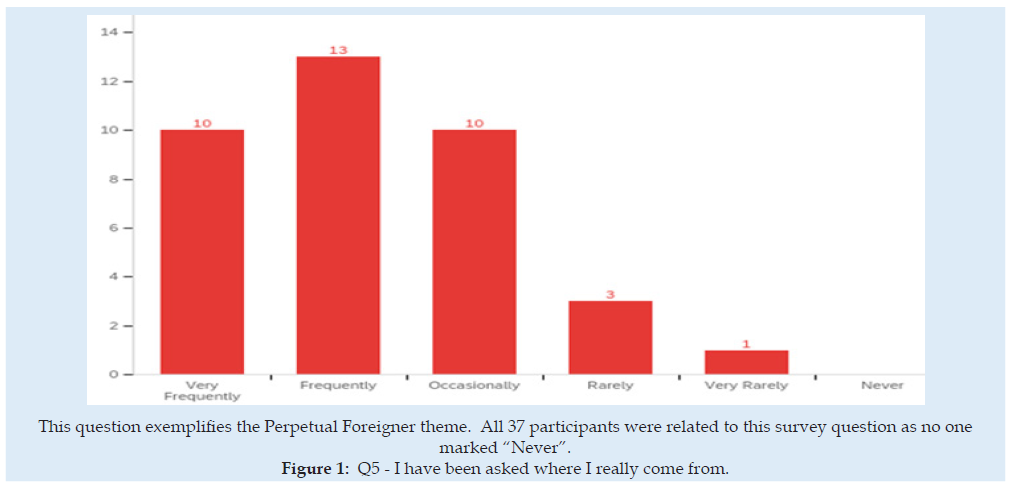

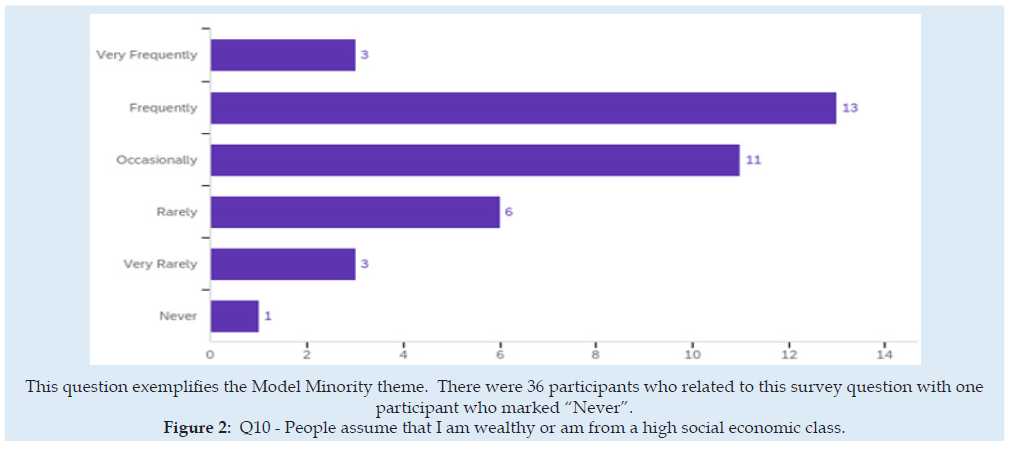

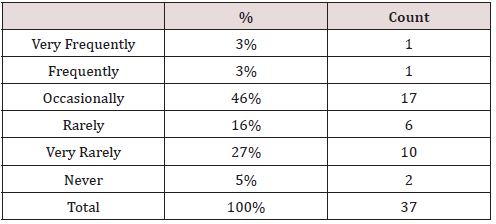

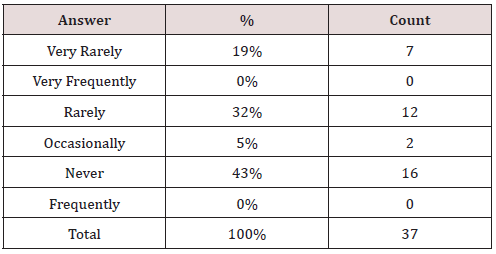

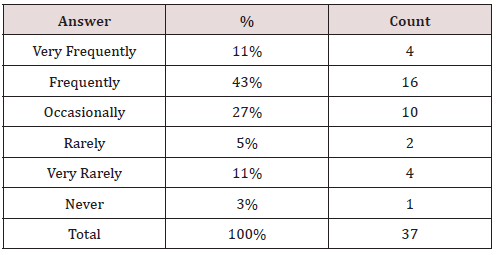

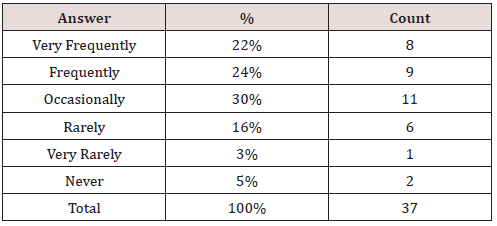

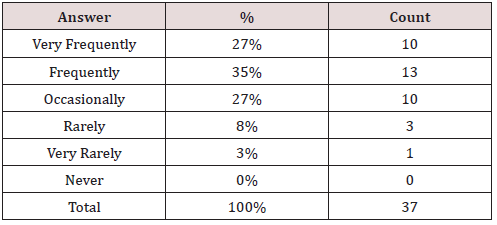

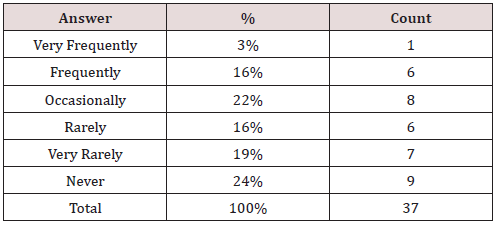

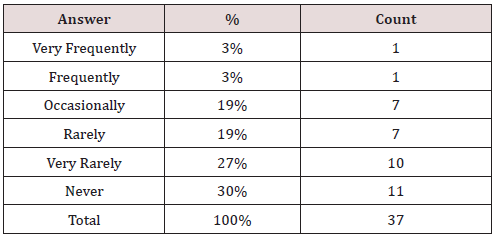

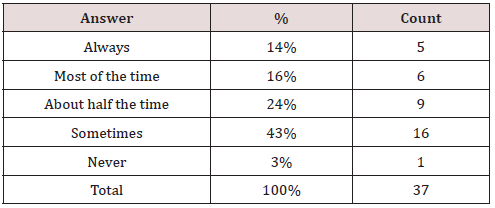

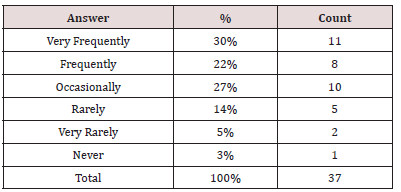

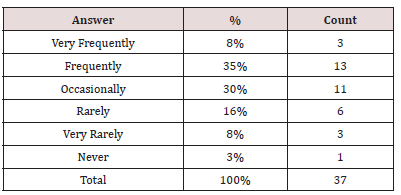

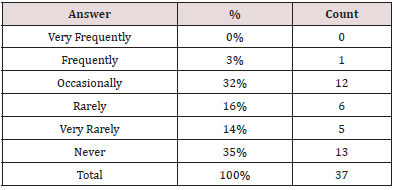

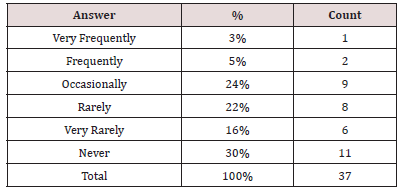

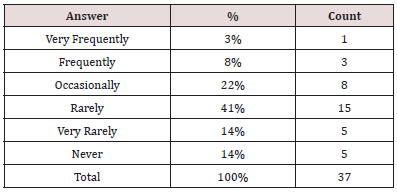

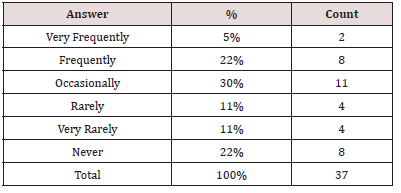

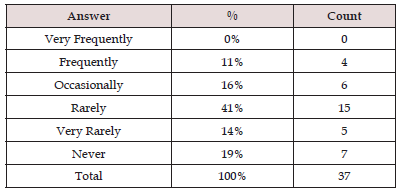

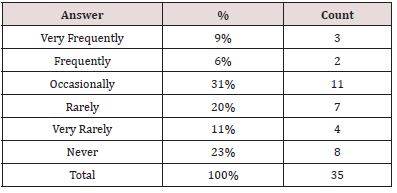

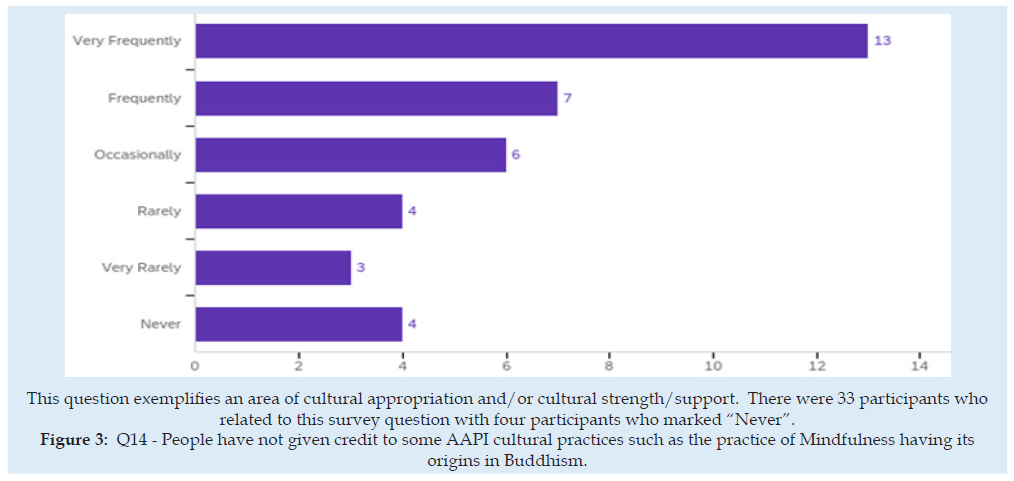

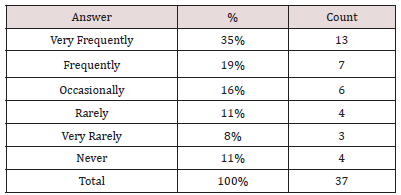

Thirty-seven participants identified as Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) and agreed to participate in the study and completed the demographic questions. The majority of participants (n=34; 92%) identified their gender as female. The largest age group was 25-34 (n=15; 41%) and their views shifted the distribution of most all items. Statistical data for all Tables and Figures were provided by K Davis. Demographics are listed in Table 1. Of the 20 questions included in the survey, there were 14 questions most closely aligned with the Perpetual Foreigner theme; there were 4 questions most closely aligned with the Model Minority theme. One question spoke to cultural appropriation and could also be seen as a source of cultural strength and support. One question was open-ended and closed the survey. The Anti-AAPI Bias Survey is listed in the Appendix. Figure 1. This question exemplifies the Perpetual Foreigner theme. All 37 participants were related to this survey question as no one marked “Never” (Figure 2). This question exemplifies the Model Minority theme. There were 36 participants who related to this survey question with one participant who marked “Never” (Figure 3). This question exemplifies an area of cultural appropriation and/or cultural strength/support. There were 33 participants who related to this survey question with four participants who marked “Never”.

Figure 3: Q14 - People have not given credit to some AAPI cultural practices such as the practice of Mindfulness having its origins in Buddhism.

Discussion

The findings of this study shows the prevalence of Anti-Asian discrimination occurs on a spectrum which has two major themes: Perpetual Foreigner and Model Minority. One new item emerged which was cultural appropriation from an AAPI practice which are sources of cultural strengths and support, e.g. Mindfulness. In the one open-ended question, three comments were most closely aligned with the Perpetual Foreigner theme and seven comments were most closely aligned with the Model Minority theme. Fourteen questions were most closely aligned with the Perpetual Foreigner theme (see Appendix). To varying degrees, participants answered affirmatively to these 14 questions.

Four questions were most closely aligned with the Model Minority theme (see Appendix). To varying degrees, participants answered affirmatively to these 4 questions. In preparation for bias, openly discussing racism and race had a mitigating effect on the mental health impacts of racism on Korean American and Filipino American children (Park et al. [12]). One question exemplifies an area of cultural appropriation and/or cultural strength/support (see Appendix) [13-15]. To varying degrees, participants answered affirmatively to this question. Ironically, it appears that some AAPI cultural practices like Mindfulness and Yoga are not associated with AAPI cultures and “mainstreamed” while other cultural practices are “othered” and are the objects of derision. Pride in ethnic heritage may blunt the effects of discrimination in Filipino American and Korean American youth (Park et al. [16]). In the one open-ended question, three comments were most closely aligned with the Perpetual Foreigner theme and seven comments were most closely aligned with the Model Minority theme (see Appendix).

Limitations

This study used a convenience sample of occupational therapy practitioners and Asian American women in academia in the U.S. which may not be wholly representative of a large swath of those who identify as Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) individuals. Another limitation of this study is the acronym “AAPI” as it was chosen to match the “Stop AAPI Hate” website acronym. However, Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) is the term used in academic settings to be more inclusive of those who identify as South Asians. Some of the questions around eye shape may have been of more pertinence to those who identify as East, Southeast Asian, and/or Pacific Islander. Additionally, the sample size was very small and did not reflect the gender, age, and class diversity within the AAPI population as a whole. The convenience sample was comprised of occupational therapy professionals as well as Asian American women in academia. Presumably all the participants were professionals, and some were in academia which is not reflective of large portions of those who identify as AAPI.

Recommendation

Further research on bias towards Asian Pacific Islander Desi Americans (APIDA) across a large sample size is needed. More specific demographic data would be helpful especially regarding age, generation in the U.S., i.e. immigrant or born in the U.S., and country of origin. Finally, future research on sources of cultural strength and resilience should be explored. Asian American studies in K-12 schools are beginning to be required as one strategy to fight against racism (Bellamy-Walker, [13-17]).

Conclusion

This study explored the spectrum of bias directed towards a convenience sample of those who identified as Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI). The brief Anti-Asian American Pacific Islander Bias Survey (AAAPIBS) was given to view how discrimination shows up from microaggressions to violence on the spectrum of Anti-Asian bias within a convenience sample of occupational therapy practitioners and Asian American women in academia in the U.S. Two themes were identified in the questions: Perpetual Foreigner and Model Minority. One question dealt with cultural appropriation of cultural strengths [18,19]. In the last open-ended question, most of the responses expressed experiencing bias in the Model Minority theme which may be influenced by the convenience sample of either occupational therapy professionals and/or Asian American women in academia. In the profession of Occupational Therapy, APIDA individuals and populations are often considered “White-Adjacent” and not People of Color (Model Minority) and/ or invisible or tokenized (Perpetual Foreigner). Yet APIDA cultural practices, e.g. Mindfulness and Yoga are mainstreamed as valued occupations without historical and cultural contexts (Cultural Appropriation). The author hopes to give voice to a rising APIDA population who are often unseen, disparaged, and silenced. The collective Pan-Asian cultures of the APIDA communities in the U.S. are sources of cultural pride, resilience, and resistance to Anti-AAPI hate.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge her occupational therapy colleagues Joe Wells, OTD, OTR/L and Luis Arabit, OTD, MS, OTR/L, Assistant Professor, San Jose State University for publishing the survey on www.asianot.org The author would like to gratefully acknowledge Claire Valderama-Wallace, PhD, MPH, RN, Assistant Professor, MSN Program Coordinator, California State University East Bay for her leadership in the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education (NCORE) Webinar Series: It’s Complicated: Asian American Women in Academia. The author is indebted to her Samuel Merritt University colleague, Kay Davis, Ed.D. who is responsible for all tables and figures used throughout the study.

Table 15: Q14 - People have not given credit to some AAPI cultural practices such as the practice of Mindfulness having its origins in Buddhism.

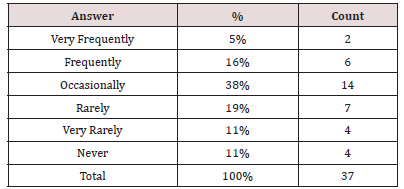

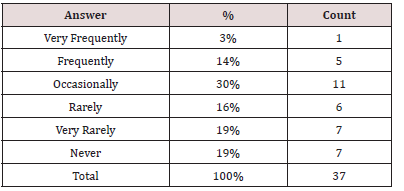

Table 17: Q16 - I do not perform or do activities I used to because I am fearful of being in public.

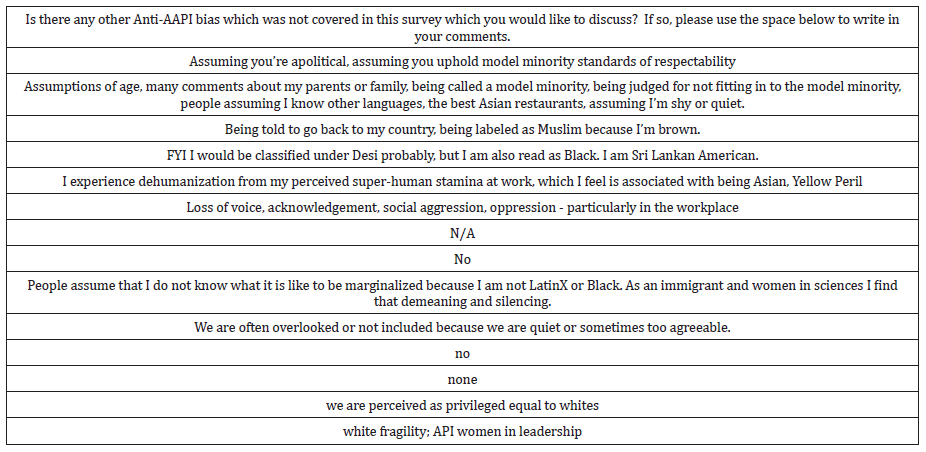

Table 21: Is there any other Anti-AAPI bias which was not covered in this survey which you would like to discuss? If so, please use the space below to write in your comments.

References

- Akiba D (2020) Reopening America’s schools during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Protecting Asian students from stigma and discrimination. Frontiers in Sociology 5(588936).

- Lee S, Waters SF (2020) Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma and Health.

- Cheng HL, Kim HY, Tsong Y, Wong J (2021) Rendered Invisible: Are Asian Americans a Model or a Minority? American Psychologist 76(4): 627-642.

- Yang JP, Nhan ER, Tung EL (2021) COVID-19 anti-Asian racism and race-based stress: A phenomenological qualitative media analysis, Psychological Trauma.

- Misra S, Le PD, Goldmann E, Yang LH (2020) Psychological impact of Anti-Asian stigma due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A call for research, practice, and policy responses. Trauma Psychology 12(5): 461-464.

- Atkin AL, Tran GTT (2020) The roles of ethnic identity and metastereotype awareness in the racial discrimination-psychological adjustment for Asian Americans at predominantly White universities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 26(4): 498-508.

- Dhahani LY, Franz B (2020) Unexpected public health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey examining Anti-Asian attitudes in the USA. International Journal of Public Health 65: 747-754.

- Wu C, Qian Y, Wilkes R (2021) Anti-Asian discrimination and the Asian-white mental health gap during COVID-19, Ethnic and Racial Studies. 44(5): 819-835.

- Wang C, Liu JL, Marsico KF, Shu Q (2021) Culturally adapting youth mental health First Aid Training for Asian Americans. Psychological Services. Advance online publication.

- McConnell C (2022) Racially Informed Care: A treatment approach and exploration of the implications of race related barriers in the United States. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy 10(1): 1-8.

- Kodama CM, Dugan JP (2020) Understanding the role of collective racial esteem and resilience in the development of Asian American leadership self-efficacy. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 13(4): 355-367.

- Park M, Yoonsun Choi, Miwa Yasui, Donald Hedeker, et al. (2021) Racial discrimination and the moderating effects of racial and ethnic socialization on the mental health of Asian American Youth. Child Development 92(6): 2284-2298.

- Bellamy-Walker T (2022) Schools are starting to mandate Asian American studies. More could follow suit.

- American Occupational Therapy Association (2007) AOTA’s Centennial Vision and executive summary. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61: 613-614.

- American Occupational Therapy Association (2016) AOTA unveils Vision 2025.

- Brown C, Stoffel VC, Munoz JP (2019) Occupational therapy in mental health: A vision for participation, (2nd), FA Davis Company.

- Brunsma DL, Embrick DG, Shin JH (2017) Graduate students of color: Race, racism, and mentoring in the white waters of academia. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 3(1): 1-13.

- Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, Greenhalgh T, Heneghan C, et al. (2011) Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine 2011 levels of evidence, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

- Murray-García JL, Harrell S, García JA, Gizzi E (2014) Dialogue as skill: Training a health professions workforce that can talk about race and racism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84(5): 590-596.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...