Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Review ArticleOpen Access

Sickle Cell Anemia Versus Sickle Cell Diseases in Adults Volume 3 - Issue 3

Mehmet Rami Helvaci1*, Hasan Yilmaz2, Atilla Yalcin1, Orhan Ekrem Muftuoglu1, Abdulrazak Abyad3 and Lesley Pocock4

1Specialist of Internal Medicine, Turkey

2Specialist of Ear, Nose, and Throat Diseases, Turkey

3Middle-East Academy for Medicine of Aging, Turkey

4Medi-WORLD International, Turkey

Received:July 15, 2021 Published:August 19, 2021

*Corresponding author:Mehmet Rami Helvaci, Specialist of Internal Medicine, MD 07400, ALANYA, Turkey

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2021.03.000163

Abstract

Background: We tried to understand prevalence and clinical severity of sickle cell anemia (SCA) alone or sickle cell diseases (SCD) with associated alpha- or beta-thalassemias in adults.

Methods: All adults with the SCA or SCD were studied.

Results: The study included 441 patients (215 females). The prevalence of SCA was significantly lower than the SCD in adults (29.0% versus 70.9%, p<0.001). The mean age and female ratio were similar in the SCA and SCD groups (31.2 versus 30.5 years and 52.3% versus 47.2%, p>0.05 for both, respectively). The mean body mass index was similar in both groups, too (21.5 versus 21.7 kg/m2, p>0.05, respectively). On the other hand, the total bilirubin value of the plasma was higher in the SCA, significantly (5.7 versus 4.4 mg/dL, p= 0.000). Whereas the total number of transfused units of red blood cells in their lives was similar in the SCA and SCD groups (43.6 versus 37.1 units, p>0.05, respectively).

Conclusion: The SCA alone and SCD are severe inflammatory processes on vascular endothelium particularly at the capillary level and terminate with an accelerated atherosclerosis and end-organ failures in early years of life. The relatively suppressed hemoglobin S synthesis in the SCD secondary to the associated thalassemia’s may decrease sickle cell-induced chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, fibrosis, and end-organ failures. The lower prevalence of the SCA in adults and the higher total bilirubin value of the plasma in them may indicate the relative severity of hemolytic process, vascular endothelial inflammation, and hepatic involvement in the SCA.

Keywords: Sickle cell anemia; sickle cell diseases; thalassemias; chronic endothelial damage; atherosclerosis; end-organ failure; metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Chronic endothelial damage may be the leading cause of aging and death. Probably whole afferent vasculature including capillaries are mainly involved in the process since much higher blood pressure (BP) of the afferent vessels may be the major underlying cause by inducing recurrent endothelial injuries. Thus, the term of venosclerosis is not as famous as atherosclerosis in the literature. Secondary to the chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis, arterial walls become thickened, their lumens are narrowed, and they lose their elastic natures, those reduce blood flow and increase systolic BP further. Some of the well-known accelerators of the atherosclerotic process are male gender, physical inactivity, excess weight, smoking, alcohol, and chronic inflammatory or infectious processes including sickle cell diseases (SCD), rheumatologic disorders, tuberculosis, and cancers for the development of irreversible consequences including obesity, hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), peripheric artery disease (PAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic renal disease (CRD), coronary heart disease (CHD), cirrhosis, mesenteric ischemia, stroke, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) those terminate with early aging and premature death. They were researched under the title of metabolic syndrome in the literature, extensively [1-3]. Although the early withdrawal of the causative factors may delay terminal consequences, the endothelial changes cannot be reversed after the development of obesity, HT, DM, PAD, COPD, CRD, CHD, stroke, or BPH due to their fibrotic natures [4-6]. Similarly, SCD are severe inflammatory processes on vascular endothelium mainly at the capillary level, terminating with an accelerated atherosclerosis and end-organ failures in early years of life [7]. We tried to understand prevalence and clinical severity of sickle cell anemia (SCA) alone or SCD with associated alpha- or beta-thalassemias in adults.

Material and Methods

The study was performed in the Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University between March 2007 and June 2016. All adults with the SCA or SCD with associated thalassemias were included into the study. The SCA and SCD are diagnosed with the hemoglobin electrophoresis performed via high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Medical histories including transfused units of red blood cells (RBC) in their lives were learnt. A complete physical examination was performed, and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated by the Same Physician instead of verbal expressions. Weight in kilograms is divided by height in meters squared [8]. A checkup procedure including a peripheral blood smear and total bilirubin value of the plasma was performed. Associated thalassemias are diagnosed by the complete blood count, mean corpuscular volume, serum iron, iron-binding capacity, ferritin, hemoglobin electrophoresis via HPLC, and genetic testing in required cases. Eventually, all patients with the SCA and SCD were detected. Mann-Whitney U test, Independent-Samples t test, and comparison of proportions were used as the methods of statistical analyses.

Results

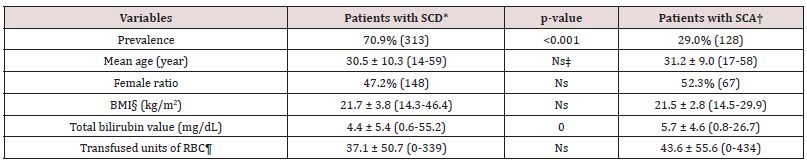

The study included 441 patients (215 females). The prevalence of the SCA was lower in the adults (29.0% versus 70.9%, p<0.001). The mean age and female ratio were similar in the SCA alone and SCD groups (31.2 versus 30.5 years and 52.3% versus 47.2%, p>0.05 for both, respectively). The mean BMI was similar in both groups, too (21.5 versus 21.7 kg/m2, p>0.05, respectively). On the other hand, the total bilirubin value of the plasma was significantly higher in the SCA (5.7 versus 4.4 mg/dL, p= 0.000). Whereas the total number of transfused units of RBC in their lives was similar in the SCA alone and SCD groups (43.6 versus 37.1 units, p>0.05, respectively) (Table 1).

*Sickle cell diseases †Sickle cell anemia ‡Nonsignificant (p>0.05) §Body mass index ¶Red blood cells

Discussion

SCD are chronic inflammatory processes on vascular endothelium terminating with an accelerated atherosclerosis induced end-organ failures in early years of life [9,10]. SCD are characterized by sickle-shaped RBC which are caused by homozygous inheritance of hemoglobin S (Hb S). They are chronic hemolytic anemias including SCA alone and SCD. The SCD are subdivided as sickle cell-Hb C, sickle cell-beta-thalassemias, and sickle cell-alpha-thalassemias. Together with thalassemias, SCA alone and SCD are particularly common in malaria-stricken areas of the world. The responsible allele is autosomal recessive that located on the short arm of the chromosome 11. Glutamic acid is replaced with valine in the sixth position of the beta chain of the Hb S. Under stressful conditions including cold, surgical operations, pregnancy, inflammations, infections, emotional distress, and hypoxia, presence of a less polar amino acid promotes polymerisation of Hb S, which distorts RBC into sickle shaped structures with a decreased elasticity. The decreased elasticity may be the major pathology of the diseases, since the normal RBC can deform to pass through capillaries easily and sickling is very rare in peripheric blood samples of the SCD with associated thalassemias. Additionally, overall survival is not affected in hereditary spherocytosis or elliptocytosis. In another word, Hb S causes RBC to change their normal elastic and biconcave disc shaped structures to hard and sickle shaped bodies. RBC can take their normal shape and elasticity after normalization of the stressful conditions, but after repeated cycles of sickling and unsickling, they become hard bodies, permanently, and the chronic endothelial damage and hemolysis develop. So the lifespan of the RBC decreases up to 15-25 days. The abnormally hardened RBC induced chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis terminate with disseminated tissue hypoxia and infarcts all over the body [11,12]. As a difference from other causes of chronic endothelial damage, the SCD may keep vascular endothelium particularly at the capillary level, since the capillary system is the main distributor of the abnormally hardened RBC into the tissues [13]. The hardened cells induced chronic endothelial damage builds up an advanced atherosclerosis in much younger ages, and the life expectancy of the SCA alone cases is decreased by 25 to 30 years [14]. On the other hand, thalassemias are chronic hemolytic anemias, too and 1.6% of the population are heterozygous for alpha- or beta-thalassemias in the world [15]. They are autosomal recessively inherited disorders, too. They result from unbalanced Hb synthesis caused by decreased production of at least one globin polypeptide chain (alpha, beta or delta) that builds up the normal Hb. HbA1 is composed of two pairs of alpha and beta chains that represents about 97% of total Hb in adults. Alpha-thalassemias result from decreased alpha chain synthesis, and beta-thalassemias result from decreased beta chain synthesis. The relatively suppressed Hb S synthesis in the SCD with associated thalassemias may decrease sickle cell-induced chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, fibrosis, and end-organ failures. The higher white blood cells (WBC) (p=000) and platelets (PLT) counts (p=007), pulmonary hypertension (p<0.05), digital clubbing (p<0.05), and autosplenectomy (p<0.001) and the lower mean hematocrit value (p<0.000) may also indicate the severity of chronic inflammatory process on vascular endothelium in the SCA alone [16]. As also observed in the present study, the total bilirubin value of the plasma may have prognostic significance due to the higher prevalences of ileus, digital clubbing, leg ulcers, pulmonary hypertension, cirrhosis, CRD, and exitus in patients with the plasma bilirubin values of 5.0 mg/dL or greater [17]. The significantly lower prevalence of the SCA alone in adults and the higher total bilirubin value of the plasma in them may indicate the relative severity of hemolytic process, vascular endothelial inflammation, and hepatic involvement in the SCA alone [17].

RBC support must be given during all medical or surgical events in which there is an evidence of clinical deterioration in the SCD, immediately [18]. For example, antibiotics do not shorten the clinical course of the acute chest syndrome (ACS) [19], and RBC support must be given early in the course since it has additional prophylactic benefits. RBC support has the obvious benefits of decreasing sickle cell concentration directly and suppressing bone marrow for the production of abnormal RBC and excessive WBC and PLT. For example, a significant reduction of ACS episodes with hydroxyurea therapy suggests that a substantial number of episodes are secondary to the increased numbers of WBC and PLT [20]. So, RBC support prevents further sickling and an exaggerated immune response induced vascular endothelial damage all over the body. According to our experiences, simple transfusions are superior to RBC exchange [21,22]. First of all, preparation of one or two units of RBC suspensions in each time rather than preparation of six units or greater provides time to clinicians to prepare more units by preventing sudden death of such high-risk patients. Secondly, transfusions of one or two units of RBC suspensions in a short period of time decrease the severity of pain, and relax anxiety of the patients and surroundings, since RBC transfusions probably have the strongest analgesic effects during the severe painful crises. Actually, the decreased severity of pain may also be an indicator of the decreased vascular inflammation all over the body. Thirdly, transfusions of lesser units of RBC suspensions in each time by means of the simple transfusions will decrease transfusion-related complications including infections, iron overload, and blood group mismatch in the future. Fourthly, transfusion of RBC suspensions in the secondary health centers can prevent some deaths developed during the transport to the tertiary health centers for the exchange. Finally, cost of the simple transfusions on insurance system is much lower than the exchange which needs trained staff and additional devices.

COPD is the third leading cause of death in the world [23]. It is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects the pulmonary vasculature. Although aging, smoking, and excess weight may be the major underlying risk factors, regular alcohol consumption may also be important in the inflammatory process. For instance, COPD was one of the most common diagnoses in alcohol dependence [24]. Furthermore, 30-day readmission rates were higher in the COPD with alcoholism [25]. Probably an accelerated atherosclerotic process is the main structural background of the COPD. The inflammatory process of the vascular endothelium is enhanced by the release of various chemicals by inflammatory cells and terminates with an advanced atherosclerosis and pulmonary losses. Although the COPD may mainly be an accelerated atherosclerotic process of the pulmonary vasculature, there are several reports about coexistence of associated endothelial inflammation all over the body [26,27]. For example, there may be close relationships between COPD, CHD, PAD, and stroke [28]. Furthermore, two-third of mortality were caused by cardiovascular diseases and lung cancers in the COPD, and the CHD was the most common cause in a multi-center study of 5.887 smokers [29]. When the hospitalizations were researched, the most common causes were the cardiovascular diseases again [29]. In another study, 27% of mortality cases were due to the cardiovascular diseases in the moderate and severe COPD [30]. As a result, COPD is one of the terminal consequences of the SCD due to the higher prevalences of priapism, leg ulcers, digital clubbing, CHD, CRD, and stroke in the SCD with COPD [31].

Digital clubbing is characterized by an increased normal angle of 165° between the nail bed and nail fold, increased convexity of the nail fold, and thickening of the whole distal finger or toes [32]. The exact cause and significance is unknown but chronic tissue hypoxia is highly suspected [33]. In the previous study, only 40% of clubbing cases turned out to have significant diseases while 60% remained well over the subsequent years [34]. But according to our experiences, digital clubbing is frequently associated with pulmonary, cardiac, renal, or hepatic disorders or smoking those are characterized by chronic tissue hypoxia [4]. As an explanation for the hypothesis, lungs, heart, kidneys, and liver are closely related organs those affect each other in a short period of time. On the other hand, digital clubbing is also common in the SCD, and its prevalence was 10.8% in another study [16]. It probably shows chronic tissue hypoxia caused by disseminated endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis at the capillary level in the SCD. Beside the effects of SCD, smoking, alcohol, cirrhosis, CRD, CHD, and COPD, the higher prevalence of digital clubbing in males (14.8% versus 6.6%, p<0.001) may also indicate some additional role of male sex on clubbing [16]. Leg ulcers are seen in 10-20% of patients with SCD [35], and the ratio was 13.5% in the above study [16]. The prevalence of leg ulcers increases with age, male gender, and SCA alone [36]. It is shown that SCA alone represents a more severe clinic than SCD with associated thalassemias [37]. Similarly, the prevalence of leg ulcers was higher in males (19.8% versus 7.0%, p<0.001), and the mean age of the patients with leg ulcers was significantly higher than the others in the above study (35.3 versus 29.8 years, p<0.000) [16]. These results may indicate effects of systemic atherosclerosis on the leg ulcers. Similarly, the leg ulcers have an intractable nature, and around 97% of ulcers relapse in a period of one year [35]. As another evidence of their atherosclerotic nature, the leg ulcers occur in distal areas with less collateral blood flow in the body [35]. The abnormally hardened RBC induced chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis at the capillary level may be the main cause in the SCD [36]. Prolonged exposure to the hardened cells due to the pooling of blood in the lower extremities may also explain the leg but not arm ulcers in the SCD. The hardened cells induced venous insufficiencies may also accelerate the process by pooling of causative RBC in the legs, and vice versa. Similarly, pooling of blood may also have some effects on the higher prevalences of venous ulcers, diabetic ulcers, Buerger’s disease, digital clubbing, and onychomycosis in the lower extremities. Furthermore, the pooling may be the cause of delayed wound and fracture healings in the lower extremities. Beside the hardened RBC, the higher prevalences of smoking and alcohol may also have some effects on the leg ulcers by accelerating the atherosclerotic process in males. Hydroxyurea is the first drug that was approved by Food and Drug Administration for the SCD [13]. It is an orally administered, cheap, safe, and effective drug that blocks cell division by suppressing formation of deoxyribonucleotides which are the building blocks of DNA [38]. Its main action may be the suppression of excessive proliferation of WBC and PLT in the SCD [39]. Although the presence of a continuous damage by hardened RBC on vascular endothelium, severity of the destructive process is probably exaggerated by the higher numbers of WBC and PLT. Similarly, lower WBC counts were associated with lower crises rates, and if a tissue infarct occurs, lower WBC counts may decrease severity of pain and tissue damage [40]. According to our ten-year experiences, prolonged resolution of leg ulcers with hydroxyurea may also suggest that the leg ulcers may be secondary to the increased WBC and PLT counts induced prolonged vascular endothelial inflammation and edema at the capillary level. Probably due to the irreversible fibrotic process on the vascular endothelium, hydroxyurea is not so effective in terminal patients with the leg ulcers.

Cirrhosis is increasing in the world and is the 11th leading cause of death globally [5]. Although the improvements of health services worldwide, the increased morbidity and mortality of cirrhosis may be explained by prolonged survival of the human being and increased prevalence of excess weight all over the world. For example, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects up to one third of the world population, and it has become the most common cause of chronic liver disease even at childhood now [41]. NAFLD is a marker of pathological fat deposition combined with a low-grade inflammation that results with hypercoagulability, endothelial dysfunction, and an accelerated atherosclerosis [41]. Beside terminating with cirrhosis, NAFLD is associated with higher cardiovascular diseases and overall mortality rates [42]. Authors reported independent associations between NAFLD and impaired flow-mediated vasodilation and increased mean carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) [43]. NAFLD may be considered as the hepatic consequence of the metabolic syndrome and SCD [9,44]. Smoking may also take role in the endothelial inflammation in the liver since the inflammatory effects of smoking on vascular endothelium is well-known with the Buerger’s disease and COPD [45]. Increased oxidative stresses, inactivation of antiproteases, and release of proinflammatory mediators may terminate with an accelerated atherosclerosis in smokers. Atherosclerotic effects of alcohol are much more prominent on hepatic endothelium probably due to the highest concentrations of its metabolites in the liver. Chronic infectious or inflammatory processes may also terminate with an accelerated atherosclerosis all over the body. For instance, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection raised CIMT, and hepatic functions were normalized with the clearance of HCV [46]. As a result, beside COPD, ileus, leg ulcers, digital clubbing, CHD, CRD, and stroke, cirrhosis may just be one of the several atherosclerotic consequences of the metabolic syndrome and SCD.

CRD is increasing all over the world, too [47]. The increased prevalence of CRD may be explained by aging of the human being and increased prevalence of excess weight, since CRD may also be one of the consequences of the metabolic syndrome [48]. Aging, male gender, physical inactivity, excess weight, smoking, alcohol, and chronic inflammatory or infectious processes may be the major underlying causes of the vascular endothelial inflammation in the kidneys. The inflammatory process is enhanced by release of various chemicals by lymphocytes to repair the damaged renal tissues, particularly endothelial cells of the renal arteriols. Due to the prolonged irritations of the vascular endothelium, prominent changes develop in the architecture of the renal tissues with an advanced atherosclerosis and subsequent ischemia and infarcts. Excess weight induced metabolic abnormalities such as hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, elevated BP, and insulin resistance may cause various cellular stresses by means of acceleration of tissue inflammation and immune cell activation [49]. For instance, age (p= 0.04), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (p= 0.01), mean arterial BP (p= 0.003), and DM (p= 0.02) had significant correlations with the CIMT [48]. Increased renal tubular sodium reabsorption, impaired pressure natriuresis, volume expansion due to activations of sympathetic nervous and renin-angiotensin systems, and physical compression of kidneys by visceral fat tissue may just be some of the mechanisms of the increased BP with excess weight [50]. Excess weight also causes renal vasodilation and glomerular hyperfiltration, initially serving as compensatory mechanisms to maintain sodium balance due to the increased tubular reabsorption [50]. However, along with the increased BP, these changes cause a hemodynamic burden on the kidneys by causing chronic endothelial damage in long term [51]. With prolonged excess weight, there are increased urinary protein excretion, loss of nephron function, and exacerbated HT. With the development of dyslipidemia and DM in the overweight and obese individuals, CRD progresses much more rapidly [50]. On the other hand, the systemic inflammatory effects of smoking on endothelial cells may also be important in the CRD [52]. The inflammatory and atherosclerotic effects of smoking are much more prominent in the respiratory endothelium due to the highest concentrations of its metabolites there. Although some authors reported that alcohol is not related with the CRD [52], it is not logical, since various metabolites of alcohol circulate even in the renal vasculature and give harm to the renal vascular endothelium. Chronic inflammatory or infectious disorders may also terminate with an accelerated atherosclerosis in the kidneys [46]. Although the CRD is mainly be thought as an advanced atherosclerotic process of the renal vasculature, there are close relationships between CRD and other atherosclerotic consequences of the metabolic syndrome and SCD [53]. For instance, the most common causes of death were the stroke and CHD in the CRD again [54]. In another definition, CRD may just be one of the several atherosclerotic consequences of the metabolic syndrome and SCD, again [55].

Stroke is an important cause of death in human being, and thromboembolism on an atherosclerotic background is the most common mechanism of its development. Aging, male gender, smoking, alcohol, excess weight and its consequences, and chronic inflammatory or infectious processes may just be some of the several accelerating factors. Stroke is also a frequent complication in the SCD [56,57]. Similar to the leg ulcers, stroke is higher in the SCA alone [58]. Additionally, a higher WBC count is associated with a higher risk of stroke [59]. Sickling induced vascular endothelial damage, activations of WBC, PLT, and coagulation system, and hemolysis may terminate with prolonged vascular endothelial inflammation, edema, remodeling, and scarring [59]. Probably, stroke is a complex and terminal event, and it may not have a macrovascular origin in the SCD. Instead disseminated capillary endothelial inflammation and edema may be much more important in the stroke. Associated inflammatory or infectious disorders or stressful conditions may precipitate the stroke, since increased metabolic rate during such episodes may accelerate the sickling. On the other hand, a significant reduction of stroke with hydroxyurea may also suggest that a significant proportion of strokes is secondary to the increased WBC and PLT counts induced disseminated capillary endothelial inflammation and edema in the brain [20].

Although the accelerated atherosclerotic process, the venous endothelium is also involved in the SCD [60]. For instance, varices are abnormally dilated veins with tortuous courses, and they usually occur in the lower extremities. Risk factors include aging, excess weight, menopause, pregnancy, and heredity. Normally, leg muscles pump veins to return blood against the gravity, and the veins have pairs of leaflets of valves to prevent blood from flowing backwards. When the leaflets are damaged, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or varices or telangiectasias develop. Varicose veins are the most common in superficial veins of the legs, which are subject to higher pressure when standing up, thus the physical examination must be performed in upright position. Although the younger mean ages of the patients in the above study (30.8 and 30.3 years in males and females, respectively) [16], and significantly lower mean BMI of the SCD patients in the literature [12], DVT or varices or telangiectasias of the lower limbs were higher in the study cases (9.0% versus 6.6% in males and females, respectively, p>0.05), indicating an additional venous endothelial involvement in the SCD [60]. Similarly, priapism is the painful erection of penis that cannot return to its flaccid state within four hours in the absence of any stimulation [61]. It is an emergency since damage to the blood vessels may terminate with a long-lasting fibrosis of the corpus cavernosa, a consecutive erectile dysfunction, and eventually a shortened, indurated, and non-erectile penis [61]. It is seen with hematological and neurological disorders, including the SCD, leukemia, thalassemia, Fabry’s disease, spinal cord lesions (hanging victims), and glucose- 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency [10,62,63]. Ischemic (veno-occlusive, low-flow), stuttering (recurrent ischemic), and nonischemic priapisms (arterial, high-flow) are the three types of the pathology [64]. Ninety-five percent of the clinical cases are the ischemic (low flow) type in which blood cannot return adequately from the penis into the systemic circulation as in the SCD, and these cases are very painful [61,64]. The other 5% are nonischemic (high flow) type, usually caused by a blunt perineal trauma in which there is a short circuit of the vascular system of the penis [61]. Treatment of high-flow type is not as urgent as the low-flow type due to the absence of risk of ischemia [61]. RBC support is the treatment of choice in acute phase in the SCD [65]. Whereas in chronic phase, hydroxyurea therapy should be the treatment of choice. According to experiences, hydroxyurea is effective for prevention of the attacks and consequences if iniatiated early in the course of the SCD, but the success rate is low due to the excessive fibrosis around the capillaries if initiated later. As a conclusion, the SCA alone and SCD with associated thalassemias are severe inflammatory processes on vascular endothelium particularly at the capillary level and terminate with an accelerated atherosclerosis and endorgan failures in early years of life. The relatively suppressed hemoglobin S synthesis in the SCD secondary to the associated thalassemias may decrease sickle cell-induced chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, fibrosis, and end-organ failures. The lower prevalence of the SCA in adults and the higher total bilirubin value of the plasma in them may indicate the relative severity of hemolytic process, vascular endothelial inflammation, and hepatic involvement in the SCA.

References

- Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Duru M, Yalcin A (2008) What is the relationship between white coat hypertension and dyslipidemia? Int Heart J 49(1): 87-93.

- Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Seyhanli M, Yalcin A (2008) White coat hypertension in definition of metabolic syndrome. Int Heart J 49(4): 449-457.

- Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Borazan A, Ozer C, Seyhanli M, et al. (2008) Metformin and parameters of physical health. Intern Med 47(8): 697-703.

- Helvaci MR, Aydin LY, Aydin Y (2012) Digital clubbing may be an indicator of systemic atherosclerosis even at microvascular level. HealthMED 6(12): 3977-3981.

- Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS (2019) Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol 70(1): 151-171.

- Helvaci MR, Seyhanli M (2006) What a high prevalence of white coat hypertension in society! Intern Med 45(10): 671-674.

- Helvaci MR, Ayyildiz O, Gundogdu M (2013) Gender differences in severity of sickle cell diseases in non-smokers. Pak J Med Sci 29(4): 1050-1054.

- (2002) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106(25): 3143-3421.

- Helvaci MR, Yaprak M, Abyad A, Pocock L (2018) Atherosclerotic background of hepatosteatosis in sickle cell diseases. World Family Med 16(3): 12-18.

- Helvaci MR, Davarci M, Inci M, Yaprak M, Abyad A, et al. (2018) Chronic endothelial inflammation and priapism in sickle cell diseases. World Family Med 16(4): 6-11.

- Helvaci MR, Ayyildiz O, Muftuoglu OE, Yaprak M, Abyad A, et al. (2017) Atherosclerotic background of benign prostatic hyperplasia in sickle cell diseases. Middle East J Intern Med 10: 3-9.

- Helvaci MR, Kaya H (2011) Effect of sickle cell diseases on height and weight. Pak J Med Sci 27(27): 361-364.

- Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, Ballas SK, Hassell KL, et al. (2014) Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 312(10): 1033-1048.

- Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, et al. (1994) Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med 330(23): 1639-1644.

- Angastiniotis M, Modell B (1998) Global epidemiology of hemoglobin disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci 30(850): 251-269.

- Helvaci MR, Arslanoglu Z, Yalcin A, Muftuoglu OE, Abyad A, et al. (2021) Pulmonary hypertension may not have an atherosclerotic background in sickle cell diseases. Middle East J Intern Med 14(1): 17-25.

- Helvaci MR, Yalcin A, Arslanoglu Z, Duru M, Abyad A, et al. (2020) Prognostic significance of plasma bilirubin in sickle cell diseases. Middle East J Intern Med 13(3): 7-13.

- Davies SC, Luce PJ, Win AA, Riordan JF, Brozovic M et al. (1984) Acute chest syndrome in sickle-cell disease. Lancet 1(8367): 36-38.

- Charache S, Scott JC, Charache P (1979) ‘‘Acute chest syndrome’’ in adults with sickle cell anemia. Microbiology, treatment, and prevention. Arch Intern Med, 139(1): 67-69.

- Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, et al. (1995) Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med, 332(20): 1317-1322.

- Helvaci MR, Atci N, Ayyildiz O, Muftuoglu OE, Pocock L (2016) Red blood cell supports in severe clinical conditions in sickle cell diseases. World Family Med, 14(5): 11-18.

- Helvaci MR, Ayyildiz O, Gundogdu M (2013) Red blood cell transfusions and survival of sickle cell patients. HealthMED 7(11): 2907-2912.

- Rennard SI, Drummond MB (2015) Early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: definition, assessment, and prevention. Lancet 385(9979): 1778-1788.

- Schoepf D, Heun R (2015) Alcohol dependence and physical comorbidity: Increased prevalence but reduced relevance of individual comorbidities for hospital-based mortality during a 12.5-year observation period in general hospital admissions in urban North-West England. Eur Psychiatry 30(4): 459-468.

- Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, Sharma G (2016) Association of Psychological Disorders With 30-Day Readmission Rates in Patients With COPD. Chest 149(4): 905-915.

- Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R (1998) Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA 279(18): 1477-1482.

- Mannino DM, Watt G, Hole D, Gillis C, Hart C, et al. (2006) The natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 27(3): 627-643.

- Mapel DW, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, Petersen HV, Picchi MA, (2000) Health care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A case-control study in a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med 160(17): 2653-2658.

- Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Enright PL, Manfreda J, (2002) Lung Health Study Research Group. Hospitalizations and mortality in the Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(3): 333-339.

- McGarvey LP, John M, Anderson JA, Zvarich M, Wise RA et al. (2007) TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee. Ascertainment of cause-specific mortality in COPD: operations of the TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee. Thorax 62(5): 411-415.

- Helvaci MR, Erden ES, Aydin LY (2013) Atherosclerotic background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in sickle cell patients. HealthMED 7(2): 484-488.

- Myers KA, Farquhar DR (2001) The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have clubbing? JAMA, 286(3): 341-347.

- Toovey OT, Eisenhauer HJ (2010) A new hypothesis on the mechanism of digital clubbing secondary to pulmonary Med Hypotheses 75(6): 511-513.

- Schamroth L (1976) Personal experience. S Afr Med J 50(9): 297-300.

- Trent JT, Kirsner RS (2004) Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care 17(8): 410-416.

- Minniti CP, Eckman J, Sebastiani P, Steinberg MH, Ballas SK (2010) Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 85(10): 831-833.

- Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Ayyildiz O (2013) Clinical severity of sickle cell anemia alone and sickle cell diseases with thalassemias. HealthMED 7(7): 2028-2033.

- Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Ayyildiz O (2013) Hydroxyurea may prolong survival of sickle cell patients by decreasing frequency of painful crises. HealthMED 7(8): 2327-2332.

- Helvaci MR, Aydogan F, Sevinc A, Camci C, Dilek I et al. (2014) Platelet and white blood cell counts in severity of sickle cell diseases. HealthMED 8(4): 477-482.

- Charache S (1997) Mechanism of action of hydroxyurea in the management of sickle cell anemia in adults. Semin Hematol 34(3): 15-21.

- Bhatia LS, Curzen NP, Calder PC, Byrne CD (2012) Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J 33(10): 1190-1200.

- Pacifico L, Nobili V, Anania C, Verdecchia P, Chiesa C, et al. (2011) Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. World J Gastroenterol 17(26): 3082-3091.

- Mawatari S, Uto H, Tsubouchi H (2011) Chronic liver disease and arteriosclerosis. Nihon Rinsho 69(1): 153-157.

- Bugianesi E, Moscatiello S, Ciaravella MF, (2010) Marchesini G. Insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Pharm Des 16(17): 1941-1951.

- Helvaci MR, Aydin LY, Aydin Y (2012) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be one of the terminal end points of metabolic syndrome. Pak J Med Sci 28(3): 376-379.

- Mostafa A, Mohamed MK, Saeed M, Hasan A, Fontanet A, et al. (2010) Hepatitis C infection and clearance: impact on atherosclerosis and cardiometabolic risk factors. Gut 59(8): 1135-1140.

- Levin A, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B, Tobe S, McFarlane P, et al. (2008) Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease. CMAJ 179(11): 1154-1162.

- Nassiri AA, Hakemi MS, Asadzadeh R, Faizei AM, Alatab S, et al. (2012) Differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors associated with maximum and mean carotid intima-media thickness among hemodialysis patients. Iran J Kidney Dis 6(3): 203-208.

- Xia M, Guerra N, Sukhova GK, Yang K, Miller CK, et al. (2011) Immune activation resulting from NKG2D/ligand interaction promotes atherosclerosis. Circulation 124(25): 2933-2943.

- Hall JE, Henegar JR, Dwyer TM, Liu J, da Silva AA, et al. (2004) Is obesity a major cause of chronic kidney disease? Adv Ren Replace Ther 11(1): 41-54.

- Nerpin E, Ingelsson E, Risérus U, Helmersson-Karlqvist J, Sundström J, et al. (2012) Association between glomerular filtration rate and endothelial function in an elderly community cohort. Atherosclerosis 224(1): 242-246.

- Stengel B, Tarver-Carr ME, Powe NR, Eberhardt MS, Brancati FL et al. (2003) Lifestyle factors, obesity and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Epidemiology 14(4): 479-487.

- Bonora E, Targher G (2012) Increased risk of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9(7): 372-381.

- Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, et al. (2006) chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 17(7): 2034-2047.

- Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Aydin LY (2013) Atherosclerotic background of chronic kidney disease in sickle cell patients. HealthMED 7(9): 2532-2537.

- DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry RC, Noetzel MJ, White DA, et al. (2014) Controlled trial of transfusions for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med 371(8): 699-710.

- Gueguen A, Mahevas M, Nzouakou R, Hosseini H, Habibi A, et al. (2014) Sickle-cell disease stroke throughout life: a retrospective study in an adult referral center. Am J Hematol 89(3): 267-272.

- Majumdar S, Miller M, Khan M, Gordon C, Forsythe A, et al. (2014) Outcome of overt stroke in sickle cell anaemia, a single institution's experience. Br J Haematol 165(5): 707-713.

- Kossorotoff M, Grevent D, de Montalembert M (2014) Cerebral vasculopathy in pediatric sickle-cell anemia. Arch Pediatr 21(4): 404-414.

- Helvaci MR, Gokce C, Sahan M, Hakimoglu S, Coskun M, et al. (2016) Venous involvement in sickle cell diseases. Int J Clin Exp Med 9(6): 11950-11957.

- Kaminsky A, Sperling H (2015) Diagnosis and management of priapism. Urologe A 54(5): 654-661.

- Anele UA, Le BV, Resar LM, Burnett AL. (2015) How I treat priapism. Blood 125(23): 3551-3558.

- Bartolucci P, Lionnet F (2014) Chronic complications of sickle cell disease. Rev Prat 64(8): 1120-1126.

- Broderick GA. (2012) Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med 9(1): 88-103.

- Ballas SK, Lyon D (2016) Safety and efficacy of blood exchange transfusion for priapism complicating sickle cell disease. J Clin Apher 31(1): 5-10.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...