Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Review ArticleOpen Access

Paternalistic Leadership and Employee Well-being in Chinese Organizations: Evidence from Taiwan and Chinese Mainland Volume 4 - Issue 5

An Chao1, Hao Yi Chen1, Dan Li2 and Henry SR Kao3

1Department of Psychology, Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan

2Department of Psychology, Sun Yat Sen University, Guangzhou

3Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Received: June 4, 2023 Published:June 27, 2023

*Corresponding author: Henry SR Kao, Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2023.04.000196

Introduction

China has emerged as an important economic power since its great progress in economic reforms from the later seventies. From 1979 to 1993, the average annual real economic growth was 9.3 percent, and Taiwan reached to the point of 8.6 percent growth in the same period Lu et al., [1]; Siu, [2]. Given continued rapid economic development, concerns about occupational health have been gaining more attention in Chinese societies. In recent years, employee well-being has turned into a popular occupational health issue. The hurt to the employees’ well-being not only makes them suffer from physical and mental discomfort and illness, but also greatly damages their organizations due to, in part, high absenteeism and medical expenditure. The United Nations International Labor Organization (ILO) (2002) estimated that, alone in the United States, the cost of lost productivity resulting from work absence is given at 200 billion dollars a year. Besides, the private business in the United States spends 423 billion dollars per year on costs for employee health insurance and services (National Center for Health Statistics, [3]). European countries also have comparable prices to pay (Cartwright & Cooper, [4]). If the loss of employee well-being is equivalent in China, which accounts for 22% of the total world population, the whole world has lost considerable resources on a global scale (Lu et al., [1]).

Two general perspectives, the top-down and the bottom-up approaches, form the bases of various models to interpret human well-being (Lu, [5]). The top-down approach focuses largely on internal factors to explain well-being (Costa & McCrae, [6,7]), like personality traits, individual cognitions, and adaptation coping efforts (Creed & Evans, [8]). On the other hand, the bottom-up approach which concentrates on the effect of situations and environments is representative of the ascription of external factors to account for one’s perception of wellness (DeNeve & Cooper, [9]). To employees, one of the most important situational factors at work is leadership. Through the interactions between leaders and subordinates, leadership is perceived by many employees to have significant influence on their well-being. For example, it was found that employees supervised with a low-consideration/high-structuring style of leadership have lower levels of job satisfaction and higher levels of health problems (Duxbury et al., [10]; Stout, [11]; Seltzer & Numerof, [12]). Subsequent research showed that harsh and abusive leadership style is positively associated with employee burnout and distress (Martin & Schinke, [13]; Tepper, [14]). More recently, Gilbreath and Benson (2004) found that employees whose supervisors engage frequently in positive behaviors and rarely in negative behaviors are more likely to report better psychological well-being.

Leadership is a culture-specific phenomenon, and its philosophy and practices are highly influenced by cultures (Hofstede, [15]). Many studies have used the emic approaches to explore leadership in the Chinese organizations, and the results have showed that leadership has great cultural difference between Chinese societies and the Western world (e.g., Cheng, [16]; Redding, [17]; Silin 18]; Westwood [19]; Westwood & Chan, [20]). The leadership style prevalent in Chinese organizations was labeled Paternalistic Leadership (PL), a culture-specific practice that has existed throughout the Chinese social and cultural history (Westwood & Chan, [20]).

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the relationship between this particular Chinese leadership style and employee well-being in Chinese work organizations. Among the forementioned researches on the leadership-employee wellbeing link, little is known about the influence of the paternalistic leadership style. Therefore, the present study is the pioneer to examine its effect on employee well-being. Besides, the present study adopts samples from Taiwan and mainland China to see if the paternalistic leadership has the same consequence to employee well-being in these two Chinese societies.

Paternalistic Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Chinese entrepreneurs and leaders manage their businesses like a family (Redding, [17]). The dynamics of management in Chinese organizations is regarded as a kind of generalized familism (Yang, [21]). One of the most salient characteristics is the “supervisory authority”, which is accompanied with keeping social distance from subordinates, intentional ambiguity, didactic behaviors, strict control, benevolence and patronage, and moral leadership (Redding [17]; Silin[18]; Westwood [19]). This leadership style is named Paternalistic Leadership (PL), which is prevalent in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or any other Chinese societies for more than two thousand years (Westwood & Chan, [20]). From the literature, paternalistic leadership is defined as “a leadership style that combines strong discipline authority with fatherly benevolence and moral integrity couched in a paternalistic atmosphere” (Cheng et al. [22]). It is made up of three important dimensions: authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, and moral leadership (Farh & Cheng, [23]).

Authoritarian leadership refers to absolute authority and dominance over the subordinates and demand for complete obedience and deference from the subordinates (Farh & Cheng, [23]). Familism is a generalized value as a common pattern of behaviors in Chinese organizations (Yang, [21]), authoritarian leadership is considered an extension of the father-son hierarchical order (Farh & Cheng, [23]). The Chinese role norms, guided by Confucianism, grant a father absolute power, legitimacy and authority over his children and other members of the family, as much as leaders possess strong authority and dominance over their subordinates in the Chinese work organizations (Cheng et al., [24]). According to Cheng et al. [22], “authoritarian leadership comprises five types of behaviors: ’powerfully subduing’, ’authority and control’, ’intention hiding’, ’rigorousness’ and ’doctrine’” (p. 91). Typically, it is very much attuned with the Theory X leadership style, which is characteristic of hierarchy, autocracy, control, and lack of trust (McGregor, [25]). Essentially, the personality traits of traditionalism and conservatism are commonly shared values that are embedded in the authoritarian style of leadership in the Chinese organizations (Kao, Xu. Kao, [26]).

Reacting to authoritarian leadership, the Chinese employees will exhibit obedience, compliance, and fear to the leader’s authority (Cheng & Farh, 27]). In traditional Chinese culture, obedience to authority was regarded as a Confucian virtue. However, in modern Chinese societies, this value has gradually faded (Cheng & Farh, [9]; Yang, [28]), especially in the younger and higher-educated generation of employees (Farh et al., [29,30]). Today, authoritarian leadership likely leads to employees’ internal conflicts instead of willing obedience. For example, it was found that authoritarian leadership evokes employees’ feeling of anger (Wu et al., 2003) and decreases job satisfaction (Cheng et al., [24]; Wu et al., [31]). Such leadership behaviors prevent or discourage the subordinates from direct interaction and communication with their bosses, and raises the subordinates’ uncertainties and misgivings (Farh & Cheng, [23]). As a result, the present study hypothesizes:

H1: Authoritarian Leadership Will Negatively Predict Employee Well-Being and Job Satisfaction.

However, compliance to leaders does not necessarily represent that subordinates will fully involve themselves in the duties (Pye, [32]). Chinese leaders thus acquire more qualities to inspire the employees at work, such as benevolence and morality. Benevolent and moral leadership resembles the Western concept of transformational leadership to the extent that both of them display individualized consideration, moral exemplars, and charisma to subordinates (Cheng et al., 22]). Benevolent leadership exhibits kindness and tolerance to employees, and grants individualized concern about employees’ job and non-job-related activities (Farh & Cheng, [23]). In Confucian ideals, an authoritative father should be merciful and tolerant to his children, and the children should reciprocate their father with reverence and filial piety (Cheng et al., [22]). Such harmonious and reciprocal interpersonal relationships are generalized from Chinese families to other social groups at large (Yang, [21]) and constitute the cornerstone of benevolent leadership in Chinese organizations.

In response to benevolent leadership, employees are expected to demonstrate gratitude, respect and repayment to the leader’s kindness and favor (Cheng et al., [22]). Benevolent leadership helps to create a cordial and supportive psychological atmosphere in the leader-follower relationship. Research has shown that benevolent leadership is positively related to employees’ satisfaction with their work (Cheng et al., [22]) as well as satisfaction with their leaders (Cheng et al., [31]). Farh and Cheng [23] investigated the personal expectation of leader behaviors from the standpoint of Chinese employees. They found that Chinese employees have high expectation of the benevolent and low expectation of the authoritarian styles of leadership. The benevolent leadership is more acceptable than the authoritarian leadership.

The third component of the PL triad model, the moral leadership, inculcates in the leader a good sense of respect from their employees owing to his demonstration of justice, integrity, unselfishness, humility and self-discipline (Farh & Cheng, [23]; Westwood & Chan, [20]). Morality is a rather important factor of Chinese leadership (Ling, [33]), which originates from the traditional Chinese approach for career assessment and its ethics system (Ling & Fang, [34]). For centuries, Chinese organizations have been characterized by the “rule by man” rather than the “rule by law” system (Yang, [35]). The “rule by law” provides the equal protection of everyone under the same regulations; however, the “rule by man” provides protection only to specific inferiors according to the superiors’ preferences. In Chinese tradition, rule by man has always been the paramount style of leadership in practice in all levels and all sectors of the society. The perception of unjust treatment leads to feelings of frustration and anger (Lambert et al., [36]). Therefore, moral leadership that emphasizes fairness and integrity may prevent employees from the detrimental effect caused by their leaders’ unjust treatment. Furthermore, in regard to the interaction effects between authoritarian and benevolent leadership, Cheng et al. [37] showed that equally high authoritarian and high benevolent leadership styles cause the subordinates the strongest work attitude; however, high authoritarian style with low benevolent leadership causes the subordinates the weakest work attitude. The positive effects of benevolent leadership may alleviate employees’ distress caused by authoritarian leadership. Therefore, the present study hypothesizes:

H2: Benevolent leadership will moderate the effects of authoritarian leadership on employee well-being and job satisfaction.

The Chinese leader’s moral leadership is reciprocated by employees’ response of respect, expectation, and identification (Cheng et al., [22]). It was found that moral leadership significantly raises employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and leaders (Cheng et al., [31]). Concerning its interaction effects with authoritarian leadership, previous research has shown a negative interaction on subordinate responses (Cheng et al., [38]). Moral leadership with an authoritarian approach imposes strict discipline upon employees and administers severe punishment to the subordinates who make mistakes regardless of any private reason or relation. Employees are likely to consider such leadership harsh and brutal, which results in decreased subordinate responses (Cheng et al., [22]). Therefore, we assume that moral leadership can increase subordinates’ wellbeing in low levels of authoritarian leadership, but may aggravate the detrimental effect of high authoritarian leadership. Thus, the present study hypothesizes:

H3: Moral leadership will moderate the effects of authoritarian leadership on employee well-being and job satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

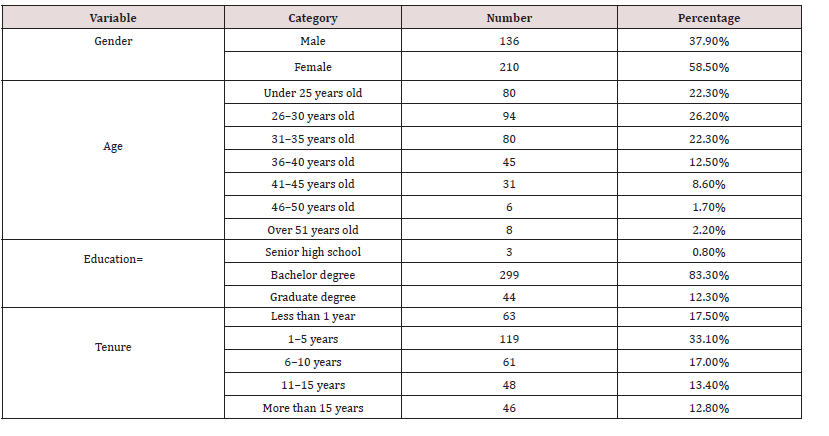

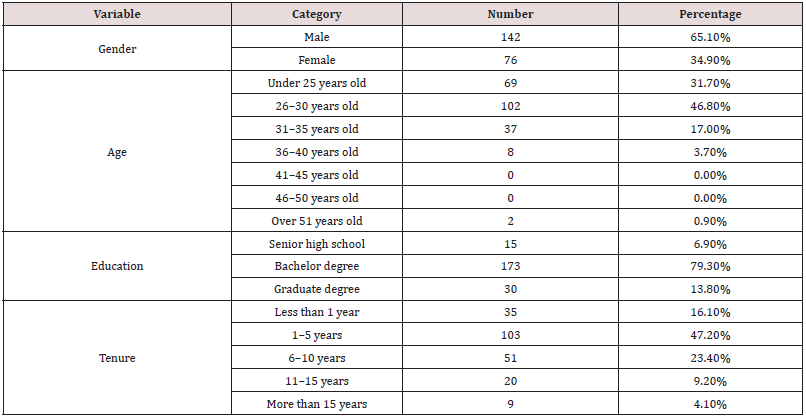

Our sample was composed of employees from Taiwan and Mainland China. The sample of Taiwan included managers (24.5%) and staff (73.0%) from 9 Taiwanese enterprises, mainly of the finance and high-technology industries. We entrusted the HR divisions of these businesses to distribute questionnaires to suitable employees. Totally 450 questionnaires were delivered, and 374 of them were returned. After data cleaning, 15 incomplete questionnaires were discarded, which left a final sample of 359. Detailed sample characteristics of Taiwanese employees are presented in Table 1. On the other hand, we recruited working adults from different enterprises in Guangdong as our sample of Mainland China. 312 questionnaires were distributed, and a total of 225 questionnaires were returned. However, after data cleaning, a final sample of 218 was left. This sample came from various industry settings, including high- technology (49.8%), private service (26.2%), education (10.2%), public service (7.1%), and finance (6.7%). Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the sample in Mainland China.

Measures

Paternalistic leadership

The revision of Paternalistic Leadership Scale (Cheng et al., [24])1 was implemented. This 51-item scale has three distinct dimensions: authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership and moral leadership. Employees rated their immediate managers by using a six-point Likert scale from 1 “strongly disagree” to 6 “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicated a stronger perception of a manager’s authoritarian, benevolent, or moral leadership behaviors. The Cronbach’s alpha from the sample of Taiwan was 0.95 for the moral leadership subscale, 0.96 for the benevolent leadership subscale, and 0.90 for the authoritarian leadership subscale. On the other hand, the Cronbach’s alpha from the sample of Mainland China was 0.90 for the moral leadership subscale, 0.88 for the benevolent leadership subscale, and 0.79 for the authoritarian leadership subscale.

Employee well-being

The 12-item mental well-being subscale and the 18-item physical well-being subscale in the Chinese version of the Occupational Stress Indicator (OSI-2) (Lu et al., [3]) were applied to the sample of employees in Taiwan. Each item was rated on a six-point Likert scale from 1 to 6, and higher scores indicated less psychological distress or somatic symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 for the mental well-being subscale and 0.85 for the physical well-being subscale.

On the other hand, the 28-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (Goldberg & Hillier, [39]) was applied to the sample of employees in Mainland China. The GHQ includes subscales measuring somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression. Each item was rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 to 3, and higher scores indicated a higher degree of psychiatric disturbance. It had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 in the sample of Mainland China.

Job satisfaction

This was measured by the 22-item Job satisfaction subscale in the Chinese version of the Occupational Stress Indicator (OSI- 2) (Lu et al., [40]). Each item was rated on a six-point Likert scale from 1 to 6, and higher scores indicated more job satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha from samples of Taiwan and Mainland China were both 0.94 in the present study.

Control variables

Demographic information, including gender, age, education, and tenure, was also collected as control variables.

Results

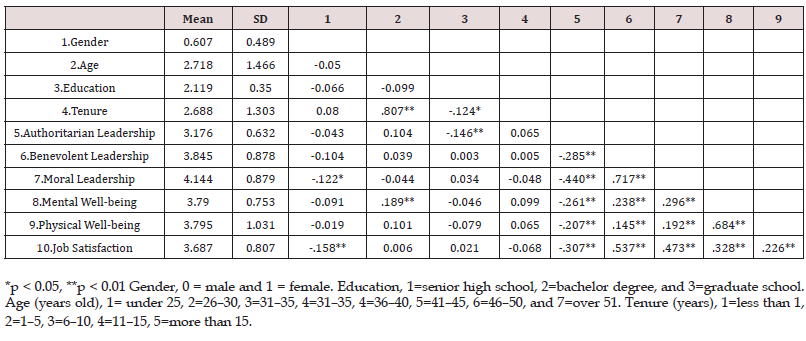

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of all of the variables among employees in Taiwan are reported in Table 3. As shown, subordinates’ gender was negatively correlated with the perception of their managers’ moral leadership (r = -.112, p <.05) and job satisfaction (r =-.158, p <.01). Subordinates’ educational level was negatively associated with authoritarian leadership (r =-.146, p <.01). It showed that mangers would demonstrate less authoritarian leadership to higher educated employees. There was a negative correlation between authoritarian leadership and employee well-being variables, like mental well-being (r =-.261, p <.01), physical well-being (r =-.207, p <.01) and job satisfaction (r =-.307, p <.01). On the other hand, there was a positive correlation between benevolent leadership and employees’ mental wellbeing (r =.238, p <.01), physical well-being (r =.145, p <.01) and job satisfaction (r =.537, p <.01), all of which were also positively associated with moral leadership (r =.296, .192 and .473, p <.01, respectively).

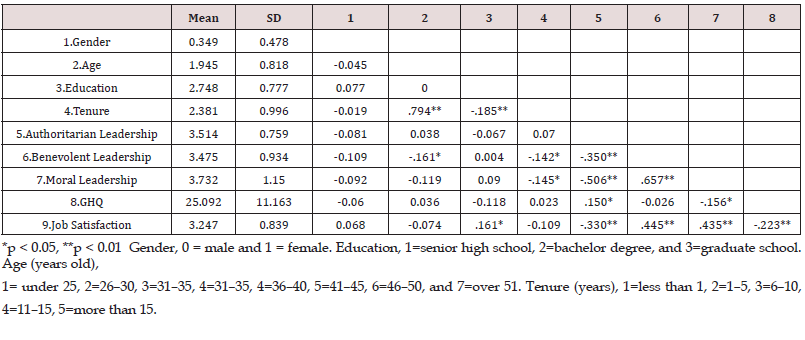

Besides, the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all of the variables among employees in Mainland China are reported in Table 4. Employees’ educational level was positively associated with job satisfaction (r =.161, p <.05), and their tenure was negatively correlated with the perception of their managers’ moral leadership (r = -.142, p <.05) and benevolent leadership (r = -.145, p <.05). Authoritarian leadership had a negative correlation with employees’ GHQ (r =.150, p <.05) and a negative relation to job satisfaction (r =-.330, p <.01). On the other hand, both benevolent leadership and moral leadership had positive correlations with employees’ job satisfaction (r =.445 and .435, p <.01), and moral leadership was also negatively related to GHQ (r =-.156, p <.05).

Hypotheses Testing

A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test the main effects of three paternalistic leadership components on employees’ well-being and the moderating effects of benevolent and moral leadership on the authoritarian leadership–employee well-being relationship while controlling for gender, age, education, and tenure. The variables were centred before the construction of interaction terms (Aiken & West, [41]).

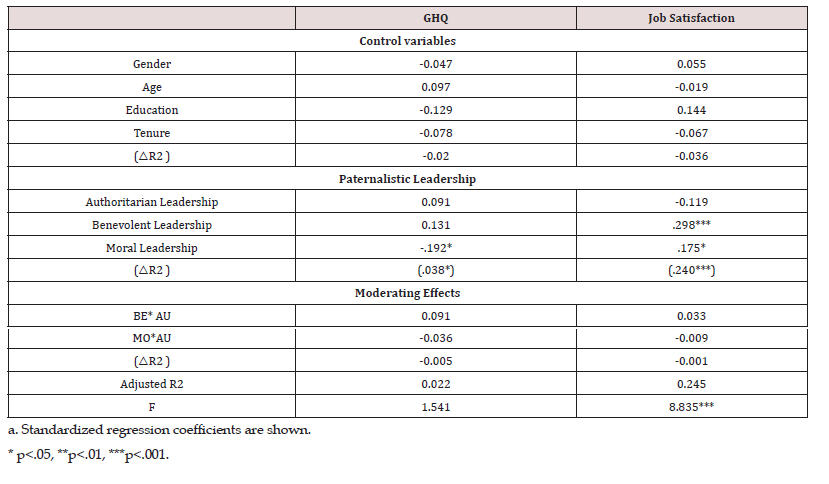

After controlling for demographic variables, the results from employees in Taiwan (see Table 5) shows that authoritarian leadership had a significant negative effect on employees’ mental well-being (β=-.236, p< .001), physical well-being (β= -.148, p< .05), and job satisfaction (β=-.185, p<.01). However, the results from employees in Mainland China (see Table 6) shows that authoritarian leadership had no significant effect on employees’ GHQ and job satisfaction. Thus, H1 is supported for employees in Taiwan but not for employees in Mainland China.

Table 5: Hierarchical regression of paternalistic leadership on employee well-being variables (Taiwanese samples, N=359).

Table 6: Hierarchical regression of paternalistic leadership on employee well-being variables: (Mainland Chinese samples, N=218).

To Taiwanese employees, benevolent leadership had a positive main effect on employees’ job satisfaction (β=.418, p <.001). On the other hand, moral leadership had positive main effects on employees’ mental well-being (β= .161, p < .05) and physical wellbeing (β=.162, p <.05). Similarly, the results from employees in Mainland China shows that benevolent leadership had a positive effect on employees’ job satisfaction (β=.298, p <.001), and moral leadership negatively influenced employees’ GHQ (β=-.192, p <.05) and positively affected their job satisfaction (β=.175, p <.05). But neither benevolent leadership nor moral leadership was a significant moderator in the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ GHQ or job satisfaction to employees in Mainland China.

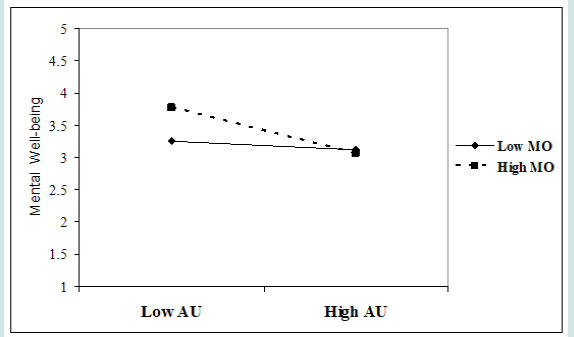

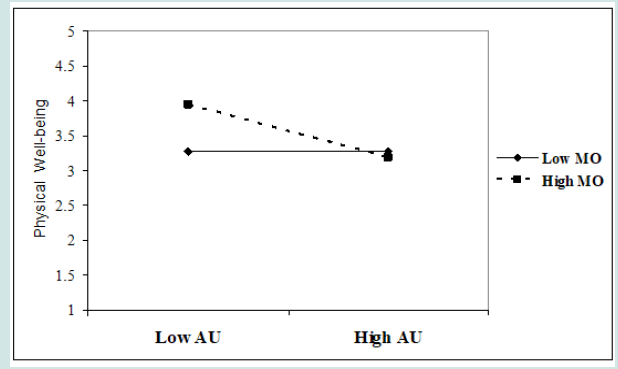

However, the results from employees in Taiwan demonstrates that benevolent leadership was a significant moderator in the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ mental well-being (β=.209, p <.05) as well as their physical well-being (β=.232, p <.01), whereas moral leadership also had significant moderating effects on the influence of authoritarian leadership on employees’ mental well-being (β=-.266, p <.01) and physical well-being (β=.-249, p <.01). As the influence of authoritarian leadership on employees’ job satisfaction, there was no significant moderating effect found by benevolent or moral leadership. Therefore, these findings can did not support H2 and H3 in Mainland China but partially did in Taiwan. The plot of the moderating effect of benevolent leadership on the authoritarian leadership–employees’ mental well-being relationship is shown in Figure 1. Similarly, Figure 2 presents its moderating effects on authoritarian leadership–employees’ physical well-being relationship. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that there is no much difference between the effects of high and low levels of benevolent leadership when employees perceived lower levels of authoritarian leadership. However, employees who received higher authoritarian leadership reported worse mental and physical well-being when they perceived lower levels of benevolent leadership than those under higher benevolent leadership. On the other hand, the plots of the moderating effect of moral leadership on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ mental and physical well-being are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 respectively. Figure 3 and Figure 4 exhibit that employees who received lower authoritarian leadership reported better mental and physical wellbeing when they perceived higher levels of moral leadership than those under lower moral leadership; but when employees perceived higher levels of authoritarian leadership, there is no difference of employees’ mental and physical well-being between high and low moral leadership conditions.

Figure 1: The moderating effect of benevolent leadership (BE) on the relationship between authoritarian leadership (AU) and employee mental well-being for Taiwanese Sample.

Figure 2: The moderating effect of benevolent leadership (BE) on the relationship between authoritarian leadership (AU) and employee physical well-being for Taiwanese Sample.

Figure 3: The moderating effect of moral leadership (MO) on the relationship between authoritarian leadership (AU) and employee mental well-being for Taiwanese Sample.

Figure 4: The moderating effect of moral leadership (MO) on the relationship between authoritarian leadership (AU) and employee physical well-being for Taiwanese Sample.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between three PL dimensions and employee well-being in two Chinese societies, mainland China and Taiwan. Our findings showed that no matter in Taiwan or Mainland China, benevolent leadership and moral leadership both have positive effect on employee well-being, whereas the authoritarian leadership demonstrates totally different effect between those two Chinese societies. Employees under benevolent leadership are granted more concerns, cares, and tolerances from their managers, and that means employees can get more social support from their leaders in the work-setting. On the other hand, employees under moral leadership are treated with fairness and justness, which is expected by employees and has significant contribution to their happiness in the workplace (Delamothe, [42]; Deutsch [43]). Authoritarian leadership is highly valued and prevalent in modern Chinese societies because it is regarded as a successful way to promote subordinate performance via authoritative control and rigorous discipline. However, empirical evidence has shown the opposite. Authoritarian leadership was found to have negative influence on team interaction and team efficiency (see Cheng et al., [24,38], Farh & Cheng [24]). On the other hand, this study demonstrated its detrimental effect from the perspective of occupational health. Authoritarian leadership decreased employees’ well-being and job satisfaction in Taiwanese samples. Those forementioned findings of three PL components showed that paternalistic leadership seems a double-edged sword, lacking its advantage due to the authoritarian dimension.

Among the Taiwanese samples, benevolent leadership and moral leadership have different moderating mechanisms between authoritarian leadership and employee well-being. High authoritarian with low benevolent leadership (i.e., high AU/low BE) are the most unhealthful, while high authoritarian with high benevolent leadership (i.e., high AU/high BE) are similar to the other two composites of low authoritarian leadership (i.e., low AU/high BE and low AU/low BE) on employee well-being. The benevolent leadership seems to play a “hygiene” role to protect employee wellbeing from the detrimental effect of authoritarian leadership. On the other hand, employees under low authoritarian but high moral leadership (i.e., low AU/high MO) have the healthier well-being than other three composites of authoritarian and moral leadership (i.e., high AU/high MO, high AU/low MO and low AU/low MO), which have similar effects on employee well-being. It seems that the moral leadership plays a “motivator” role to enhance employee well-being along with the positive effect of low authoritarian leadership.

Our study showed that the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee well-being and job satisfaction is not significant in Mainland China, which is consistent with Wu et al.’s [37] and Cheng et al.’s [31] findings that revealed authoritarian leadership decreases employees’ job satisfaction in Taiwan (Wu et al., [37]), but has no significant influence on employees’ job satisfaction in mainland China (see Cheng et al., [31]). Since the levels of authoritarian leadership in those two Chinese areas are similar, such difference may come from employees rather than their managers. The present study suggests that employees’ response to the authoritarian leadership is a main factor to influence their well-being. Compliance to the authority was regarded as a Chinese traditional virtue. According to this social rule underlying Confucianism, Chinese employees should demonstrate compliance and fear to the authorities (Cheng & Farh [27]). Authoritarian behaviors, such as powerful control, underestimation of subordinate competence, and rigorous didacticism, easily trigger subordinates’ anger (Wu et al [37]). Even though employees feel angry to their leaders, they have to suppress their anger in order to be compliant and obedient. Wu et al. [37] found that supervisors’ authoritarian behaviors can predict the subordinates’ tendency to suppress anger, which is detrimental to psychological adjustment (Bromberger & Matthew, [44]; Goldman & Haaga, [45]) and physical health (Eysenck, [46]; Fernandez-Ballesteros et al., [47]).

We suggested that employees in Mainland China are more likely to express their angry feelings to the authoritative leaders rather than to inhibit the anger. Such difference in coping with authoritarian leadership may derive from different levels of Confucianism conservation between Taiwan and Mainland China. Confucianism in Taiwan has been always well conserved and promoted through educational systems. No matter in families, schools, work settings, interpersonal relationship commonly follows the norms of respect for authorities and hierarchical order (Chun, [48]). However, in Mainland China, Confucianism was greatly destroyed since the May Fourth Movement in 1919. The Cultural Revolution during 1966 to 1976, when the China government inspired people to rebel the tradition authority and hierarchical order, brought about the downfall of Confucianism (Wang & Zhao, [49]). Despite the revival by the academics and officials after 1980s, Confucianism in Mainland China is not as prevalent and habitual in the public lives as Taiwan. The mainlanders seem to be more liberated from the traditional past that the populace in Taiwan, where traditionalism remains the norms of the day. With less social expectation or internalization to obey authorities, employees in Mainland China are inferred to be more resilient to authoritarian leadership, which may weaken its detrimental effect to employees’ well-being.

study suggested that both benevolent leadership and moral leadership can improve employees’ well-being and job satisfaction, while authoritarian leadership, which baffles communication between leaders and subordinates, has essentially negative influence. However, whether authoritarian leadership will take effect is influenced by employees’ coping strategy. For subordinates with high authority orientation and who value compliance and obligations (e.g., employees in Taiwan), authoritarian leadership shows a larger effect on their well-being. For subordinates who emphasize equal rights (e.g., employees in mainland China), the bad influence of authoritarian leadership to employees’ well-being is low or even non-existent. The results implied that the management has to adjust paternalistic leadership to modern Chinese organizations. Authoritarian leadership should be forsaken, but benevolent leadership and moral leadership, such as personal care, forgiving and consideration towards subordinates, should be applied in order to evoke employee’s positive response and efficacy. For employees, the best way to response to authoritarian leadership is not obedience but to communicate and express feelings in a proper way.

However, results from the study sample of 160 local and non-Chinese subordinates from 31 overseas branches of a giant selected, large, Chinese multinational enterprise (MNE), showed that the moral and authoritarian styles of the Chinese paternalistic leadership contributed negatively to psychological health in the workplace, a different pattern of results from studies completed with Chinese subordinates in previous research including those obtained from the present study. This reflects that the greater the discrepancy is between the visiting Chinese style of authoritarian leadership style from the hosting cultural conditions, the worse is the reception and negative psychological impacts are on the local employees (Chen & Kao, [50-52]).

Endnotes

The revised edition of the PL Scales used in the present study was developed and provided by the originators of Paternalistic Leadership Scale (Cheng et al., [6]).

References

- Lu L, Cooper CL, Kao SF,Zhou Y (2003) Work stress, control beliefs and well-being in Greater China: An exploration of sub-cultural differences between the PRC and Taiwan. Journal of Managerial Psychology 18: 479-510.

- Siu OL (2003a) Job stress and job performance among employees in Hong Kong: The role of Chinese work values and organizational commitment. International Journal of Psychology 38(6): 337-347.

- National Center for Health Statistics (2005) Health, United States, 2005 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans with special feature on adults 55-64 years. Hyattsville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services.

- Cartwright S, Cooper C (1997) Managing workplace stress. London: Sage Publications.

- Lu L (1999) Personal and environmental causes of happiness: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Social Psychology 139(1): 79-90.

- Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR (1980) Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38(4): 668-678.

- Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR (1984) Personality as a lifelong determinant of wellbeing. In C. Z. Malatesta & C. E. Izard (Eds.), Emotion in adult development (pp. 141-157). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Creed PA, Evans B (2002) Personality, well-being and deprivation theory. Personality and Individual Differences 33(7): 1045-1054.

- DeNeve KM, Cooper H (1998) The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 124(2): 197-229.

- Duxbury ML, Armstrong GD, Drew DJ, Henly SJ (1984) Head nurse leadership style with staff nurse burnout and job satisfaction in neonatal intensive care units. Nursing Research 33(2): 97-101.

- Stout JK (1984) Supervisors’ structuring and consideration behaviors and workers’ job satisfaction, stress, and health problems. Rehabilitation Bulletin 28: 133-138.

- Seltzer J, Numerof RE (1988) Supervisory leadership and subordinate burnout. Academy of Management Journal 31: 439-446.

- Martin U, Schinke SP (1998) Organizational and individual factors influencing job satisfaction and burnout of mental health workers. Social Work in Health Care 28(2): 51-62.

- Tepper B J (2000) Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal 43: 178-190.

- Hofstede G (1980) Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, California: Sage Publications.

- Cheng BS (1995) Hierarchical structure and Chinese organizational behavior. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies 3: 142-219.

- Redding SG (1990) The spirit of Chinese capitalism. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Silin RF (1976) Leadership and values. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Westwood RI (1997) Harmony and patriarchy: The cultural basis for ‘paternalistic headship’ among the overseas Chinese. Organization Studies 18(3): 445–480.

- Westwood RI, Chan A (1992) Headship and leadership. In R. I. Westwood (Ed.), Organizational behavior: A Southeast Asian perspective (pp. 123–139). Hong Kong: Longman.

- Yang, KS (1995) Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis. In T.Y. Lin, W.S. Tseng & E.K. Yeh (Eds.), Chinese societies and mental health (pp. 19-39). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- Cheng BS, Chou LF, Wu TY, Huang MP,Farh JL(2004) Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organization. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 7(1): 89-117.

- Farh JL, Cheng BS (2000) A Cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In J. TLi, Tsui AS, E Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in the Chinese context (pp. 84–127). London: Macmillan.

- Farh JL, Cheng BS (2000) A Cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In J. TLi, Tsui AS, E Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in the Chinese context (pp. 84–127). London: Macmillan.

- McGregor D (1960) The human side of enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kao HS R, Xu M, Kao TT (2021) Calligraphy, Psychology and the Confucian Literati Personality. Psychology and Developing Societies 1-19.

- Cheng BS, Farh JL (2001) Social orientation in Chinese societies: A comparison of employees from Taiwan and Chinese Mainland. Chinese Journal of Psychology 43: 207–221.

- Yang KS (1996) Theories and research in Chinese personality: An indigenous approach. In H. S. R. Kao & D. Sinha (Eds.), Asian perspectives on psychology. New Delhi, India: Sage.

- Farh JL, Earley, PC, Lin SC (1997) Impetus for action: A cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behaviour in Chinese society. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 421–444.

- Farh JL, Leung F, Law K (1998) On the cross-cultural validity of Holland’s model of vocational choices in Hong Kong. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 52(3): 425–440.

- Cheng BS, Chou LF, Huang MP, Farh JL, Peng SQ (2003) A triad model of paternalistic leadership: Evidence from business organizations in mainland China. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies 20: 209–250.

- Pye LW (1985) Asian power and politics: The cultural dimension of authority. Cambridge Massachsets: Harvard University Press.

- Ling WQ (1989) Pattern of leadership behavior assessment in China. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient 32(2): 129-134.

- Ling WQ, Fang LL (1994) Theories on leadership and Chinese culture: The formulation of the CPM model on leadership behavior and a Chinese ‘implicit’ theory on leadership traits. In H. S. R. Kao, D. Sinha, & S. H. Ng. (Eds.), Effective organizations and social values (pp. 257-286). India, New Delhi: Sage.

- Yang MH (1994) Gifts, favors and banquets: The art of social relations in China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Lambert E, Cluse-Tolar T, Pasupuleti S, Hall D, Jenkins M (2005) The impact of distributive and procedural justice on social service workers. Social Justice Research, 18(4): 411-427.

- Wu TY, Hsu WL, Cheng BS (2003) Expressing anger? Or suppressing anger? Subordinates’ anger responses to supervisors’ authoritarianist behaviors in Chinese business. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 19, 3–49 (in Chinese).

- Cheng BS, Huang MP, Chou LF (2002. Paternalistic leadership and its effectiveness: Evidence from Chinese organizational teams. Journal of Psychology in Chinese Societies 3(1): 85-112.

- Goldberg D, Hillier V (1979) A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychological Medicine 9(1): 139 -145.

- Lu L, Cooper CL, Chen YC, Hsu CH, Wu, HL, et al. (1997) Chinese version of the OSI: A validation study. Work & Stress 11: 79-86.

- Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Delamothe T (2005) Happiness. British Medical Journal 331(7531): 1489-1490.

- Deutsch M (1985) Distributive justice: A social psychological perspective. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Bromberger JT, Matthews KA (1996) A "feminine" model of vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal investigation of middle-aged women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70(3): 591-598.

- Goldman L, Haaga DAF (1995) Depression and the experience and expression of anger in marital and other relationships. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183(8):505–509.

- Eysenck HJ (1994) Cancer, personality and stress: Prediction and prevention. Advances in Behavior Research and Therapy 16(3): 167-215.

- Fernandez-Ballesteros R, Ruiz MA, Garde S (1998). Emotional expression in healthy women and those with breast cancer. British Journal of Health Psychology 3(1): 41–50.

- Chun A (1994) From nationalism to nationalizing: Cultural imagination and state formation in postwar Taiwan. The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 31: 49-69.

- Wang S,Zhao W (2006) China's peaceful rise: A cultural alternative. Boundary2 33(2): 117-127.

- Chen HY, Kao H SR (2009) Chinese paternalistic leadership and non-Chinese subordinates’ psychological health. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 20(12): 2533–2546.

- Gilbreath B, Benson P (2004) The contribution of supervisor behaviour to employee psychological well-being. Work and Stress 18(3): 255-266.

- United Nations International Labor Organization (1993) Job stress: the 20th century disease. In Office WLR (Ed.), World labor report. Geneva: United Labor Office, United Nations.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...