Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Review ArticleOpen Access

Low Fodmap Diet for Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Ibs) Volume 4 - Issue 1

Maryame Kadiri Hassani Dietitian*

UK registered associate Nutritionist

Received: June 1, 2022 Published: June 15, 2022

*Corresponding author: Maryame Kadiri Hassani Dietitian, UK registered associate Nutritionist, UK

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2022.04.000177

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic disorder that affects a large part of the population. This disorder is the most common diagnosis made by gastroenterologists around the globe (El-Salhy, [1]). IBS is known to be more frequent in younger people and women (NICE, [2]). The causes of IBS are unknown, although some risk factors might contribute to its development. (El-Salhy, [1]). IBS is characterised by occurrent abdominal pain or discomfort, associated with a change in bowel movement (Longstreth et al.,). There is no specific cure for IBS. However, symptoms could be managed by making some changes in diet and lifestyle. Having a low Fermentable Oligosaccharide, Disaccharides, Monosaccharide and Polyols (FODMAP) diet accompanied by other lifestyle and pharmacological approaches is recommended to control IBS symptoms (Mckenzie [3]: 460).

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Ibs)

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional disorder of the lower gastrointestinal tract, in which abdominal pain or discomfort is associated with defecation and or a change in the stool output (World Gastroenterology Organisation [4]). In the world, 10 to 15% of the population is estimated to have IBS (IFFGD, 2016). Also, the worldwide prevalence of IBS is between 7 and 21% (Lovel and Ford). In the UK, the prevalence of IBS in the whole population is between 10 and 20%. Also, the prevalence is twice higher among women than among men, and it is common in people aged between 20 and 30 years (NICE [5]). IBS symptoms might be generated by multiples mechanisms, including genetic and psychological factors, visceral hypersensitivity, food hypersensitivity, inflammatory mechanisms and dietary components as well as gastrointestinal microbiota (Adam and Qasim [6]: 226-229). IBS may be classified into four principal subtypes, including (IBS-D) IBS with diarrhoea, (IBS-C) IBS with constipation, (IBS-M) IBS with mixed symptoms of diarrhoea and constipation as well (IBS-U) un-subtyped (Mearin et al., [7]). IBS has many negative impacts on patients suffering from this disorder. It has been reported that people with IBS have a lower quality of life compared to the healthy population, and also to the population with asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease and migraine (Frank et al., [8]). There is no cure for IBS, however, it is recommended for IBS patients to get a dietary (for example low FODMAP diet), pharmacological and psychological treatment to manage the symptoms (Spiller et al., )

Low Fodmap Diet

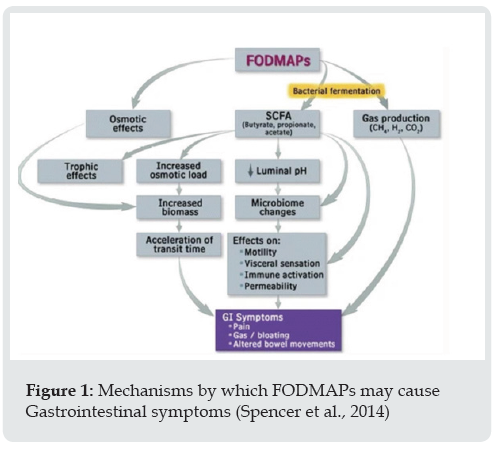

FODMAP is the acronym for Fermentable Oligosaccharide, Disaccharides, Monosaccharide and Polyols. They are the categories of the short chain carbohydrates found in many foods including fruits, vegetables and in dairy and wheat products. They consist of fructose, lactose, fructo‐ and galacto‐oligosaccharides (fructans, and galactans), and polyols including sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol and maltitol (Gibson and Shepherd, [9]). FODMAPs are poorly absorbed in the small intestine which leads to an osmotic effect increasing water in the intestines and gas production. Gas production is caused by rapid fermentation by bacteria. These effects may induce gastrointestinal symptoms after ingestion of FODMAP’s in patients with visceral hypersensitivity (Shepherd et al., 2013). (Figure 1).

Many health organisations have recommended a low FODMAP diet to manage irritable bowel syndrome. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for IBS management recommended a low FODMAP diet for the management of IBS in primary care (NICE [2]). Moreover, the latest British Dietetic Association guideline for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome; recommended as a second line after healthy eating, the low FODMAP diet (McKenzie et al., [3]). Also, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guideline recommended a low FODMAP diet in patients with IBS to improve global symptoms (Lacy et al., [10]). There are 3 stages of the low FODMAP diet; the first one is FODMAP restriction which takes between 2 to 8 weeks, FODMAP intake is reduced to below the tolerance in this stage; the second one is FODMAP reintroduction which takes between 6 to 10 weeks, FODMAP containing foods are consumed with moderation and with symptoms monitoring; and the last one is FODMAP personalization which is a long-term self-management period (Whelan et al., [11]).

Low Fodmap Diet and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Ibs)

Many studies have been done to assess the effect of a low FODMAP diet on IBS. Nawawi et al [12] have investigated the impact of the low FODMAP diet on 164 patients with IBS in a period of 12 months including the second phase of the diet (re-introduction). There was a significant improvement (p < 0.0001) in all symptoms (lethargy, bloating, flatulence and abdominal pain) of the 127 patients that completed the 3 months follow-up; the improvement was also observed in the 74 patients that continued the follow-up at 6 and 12 months. Furthermore, the symptomatic response was maintained after the re-introduction of the high FODMAP food.

A meta-analysis has been done to assess the effects of a low FODMAP diet on the symptoms of IBS. This study included 9 randomized controlled trials that compare between low FODMAP diet and other diets. The total number of participants was 614 and the follow-up period was from 48 hours to 3 months. As a result, a significant difference related to gastrointestinal symptoms and abdominal pain was found when comparing a low FODMAP diet to other diets. The standardized mean difference was low by 0.62 for gastrointestinal symptoms and low by 0.5 for abdominal pain (Schumann et al., [13]). Furthermore, another quiet similar metaanalysis has included 9 randomized controlled trials, with a total of 542 participants. This study reviewed the quality of trials on the symptomatic effects of the low FODMAP diet for IBS. Therefore, it has been concluded that randomized controlled trials on the low FODMAP diet have a high risk of bias, this is because there is a lack of proper blinding and in the choice of a control group. Also, the majority of the available studies are done in less than 6 weeks (Krogsgaard et al., [14]). Further studies could assess the long-term effects of a low FODMAP diet on IBS to minimise the bias. Many results of randomised trials for the effect of a low FODMAP diet were positive. However, other diets may be as effective as the low FODMAP. A study compared the low FODMAP diet with traditional dietary advice. The total population was 67, with 33 patients having a low FODMAP diet and 34 patients having a traditional dietary advice. In both groups, the severity of IBS symptoms was reduced during the 4 weeks of the intervention (P < 0.0001 in both groups), with no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.62). Besides, a similar improvement of symptoms (bloating, abdominal pain) was observed in both groups (Böhn et al., [15]). However, having a low FODMAP diet may have some impact on nutrient intake. A study evaluated the nutrient intake and diet quality of patients following a low FODMAP diet (n= 63) by comparing them to patients having a sham diet (n=48) or a habitual diet (n=19). This study was conducted in a period of 4 weeks. Therefore, it has been found that fibre intake was low by 5% to the target in patients having a low FODMAP diet. There was also a low intake of starch compared to the control diet (P=0.030), and a high intake of vitamin B12 compared to other diets (P<0.01). Moreover, there was no difference in most nutrient intake compared to other diets. However, diet quality decreased in the low FODMAP diet compared to the other diets (Staudacher et al., [16]). Another study compared the nutrient intake of the low FODMAP diet by comparing it to mNICE diet. The total cohort was 78 patients, 41 had the low FODMAP diet and 37 the mNICE DIET. After 4 weeks of intervention, a statistically significant reduction in mean daily intake was observed in thiamin (P <0.01) riboflavin (P <0.05), calcium (P <0.01) and sodium (P <0.001) among patients following the low FODMAP diet. Besides, mNICE patient had no reductions in their nutrient intake. Moreover, there was no change in macronutrient intake in both groups (Eswaran et al., [17-23]).

Conclusion

From the studies covered above, it can be concluded that the low FODMAP diet have a positive effect on the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Most of the symptoms are reduced when taking the diet. The majority of the studies available are done in a short term, Long-term effects of a low FODMAP diet has to be more investigated. Moreover, IBS patients need to have a dietary education by a specialist dietician when starting a low FODMAP diet, this is to prevent getting a low nutrient intake, also, to get better outcomes and minimise mistakes.

References

- El-Salhy M (2012) Irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis and pathogenesis. World Journal of Gastroenterology 18(37): 5151-5163.

- NICE (2008) Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults: Diagnosis and Management Clinical Guideline.

- Yvonne Mckenzie (2014) Irritable bowel syndrome , in Gandy, J. (ed.) Manual of Dietetic Practice. 5th edn. UK: Willey Blackwell, pp. 460.

- World Gastroenterology Organization Global (2015) Guidelines irritable bowel syndrome: A global perspective update September 2015, Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 50(9): pp.704-713.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, (NICE) (2013) Faecal Calprotectin Diagnostic Tests for Inflammatory Diseases of the Bowel Diagnostics guidance Diagnostics Guidance DG11.

- Adam d Farmer, Qasim Aziz (2014) Irritable bowel syndrome pathogenesis, in Lomer, M. (ed.) Advanced Nutrition and Dietetics in Gastroenterology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, pp. 226-229.

- Fermín Mearin , Brian E Lacy , Lin Chang , William D Chey , Anthony J Lembo, et al. (2016) Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology S0016-5085(16)00222-5.

- Lori Frank , Leah Kleinman, Anne Rentz, Gabrielle Ciesla, John J Kim, et al. (2002) Health-related quality of life associated with irritable bowel syndrome: Comparison with other chronic diseases, Clinical Therapeutics 24(4): 675-689.

- Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ (2010) Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach, Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 25(2): 252-258.

- Lacy BE (2021) ACG clinical guideline: Management of irritable bowel syndrome, Official Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG, 116(1).

- K Whelan, L D Martin, H M Staudacher, M C E Lomer (2018) The low FODMAP diet in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: An evidence‐based review of FODMAP restriction, reintroduction and personalisation in clinical practice, Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics 31(2): pp.239-255.

- Nawawi KNM, Belov, M, Goulding C (2020) Low FODMAP diet significantly improves IBS symptoms: An irish retrospective cohort study, European Journal of Nutrition 59(5): 2237-2248.

- Dania Schumann, Petra Klose, Romy Lauche, Gustav Dobos, Jost Langhorst, et al. (2018) Low fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyol diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Nutrition 45: 24-31.

- Krogsgaard LR, Lyngesen M, Bytzer P (2017) Systematic review: Quality of trials on the symptomatic effects of the low FODMAP diet for irritable bowel syndrome, Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 45(12): 1506-1513.

- Böhn L, Stine Störsrud, Therese Liljebo, Lena Collin, Perjohan Lindfors, et al. (2015) Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: A randomized controlled trial, Gastroenterology 149(6): 1399-1407.e2.

- Heidi M Staudacher, Frances S E Ralph, Peter M Irving, Kevin Whelan, Miranda C E Lomer (2020) Nutrient intake, diet quality, and diet diversity in irritable bowel syndrome and the impact of the low FODMAP diet, Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics 120(4): pp. 535-547.

- Shanti Eswaran, Russell D Dolan, Sarah C Ball, Kenya Jackson, William Chey (2020) The impact of a 4-week low-FODMAP and mNICE diet on nutrient intake in a sample of US adults with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea, Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics, 120(4): 641-649.

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders, (IFFGD) (2016) Facts about IBS.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC (2012) Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology : The Official Clinical Practice Journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 10(7): 712-721.e4.

- Y A McKenzie , R K Bowyer , H Leach , P Gulia , J Horobin, et al. (2016) British dietetic association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update), Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics 29(5): 549-575.

- Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC and Gibson PR (2013) Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 108(5): 707-717.

- Spencer M, Chey WD, Eswaran S (2014) Dietary renaissance in IBS: Has food replaced medications as a primary treatment strategy? Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 12(4): 424-440.

- Spiller R (2007) Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: Mechanisms and practical management, Gut, 56(12): 1770-1798.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...