Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Research ArticleOpen Access

Effects Of Forest Bathing (Forest Therapy) And Diaphragmatic Deep Breathing Exercise on Pre- Hypertensive/Hypertensive Adults in Hong Kong: A Quasi- Experimental Feasibility Study Volume 3 - Issue 4

Katherine Ka-Yin YAU1, RN, MCNS, DHSc, Alice Yuen LOKE2*, RN, MN, PhD

1Senior Lecturer, School of Nursing, Tung Wah College, Hong Kong.

2Honorary Professor, School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong.

Received: October 18, 2021 Published: November 08, 2021

*Corresponding author: Prof. Alice Yuen LOKE, Director and Professor, Department of Nursing, Hong Kong Adventist College, Hong Kong

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2021.03.000170

Abstract

This study aimed to examine and compare therapeutic effectiveness between forest bathing (FB) and diaphragmatic deep breathing exercise (DDBE) in middle-aged adults with pre-hypertension or hypertension in Hong Kong. Four sessions each of FB and DDBE were conducted among eligible participants in a country park (n=21) and a quiet room (n=12), respectively. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse rate (PR), mood states, and state and trait anxiety levels were measured before (baseline) and immediate before and after each intervention, and eight weeks post intervention. After four consecutive weeks of intervention, the FB group achieved a significant decrease in SBP 7.4 mmHg and a significant reduce in the scores of state anxiety level of 11.5, trait anxiety levels of 6.4, the total mood states of 14.8, tension-anxiety of 3.2, depression of 2.0, fatigue of 4.1, anger of 2.3 and confusion of 2.0. DDBE intervention showed no effect on lowering SBP, DBP and PR, but it showed a significant decrease in the scores of state anxiety level of 8.0, trait anxiety level 6.2, total mood states 9.0, tension-anxiety 1.6 and confusion 1.8. FB was more effective in lowering SBP, state and trait anxiety levels, and improving negative mood, while DDBE was more effective in decreasing PR. At eight weeks after intervention, only FB had a significant sustained effect on lowering PR of 6.9 beats/ min. These findings provide preliminary evidence that FB is more effective than DDBE in lowering SBP and anxiety levels in the study population.

Keywords: forest bathing; diaphragmatic deep breathing exercise; hypertension; prehypertension; anxiety; mood state

Introduction

Hypertension have been reported to be associated with

coronary vascular disease and cerebrovascular diseases [1,2].

The prevalence of hypertension is estimated to impact 29% of the

population by 2025 [1]. The pre-hypertension definition (120-139

mmHg and/or 80-89 mmHg) relatively recently established is to

alert adults with pre-hypertension of the high risk of hypertension

and the resulting cardiovascular diseases [3]. Hypertension is

defined when systolic blood pressure (SBP) is ≥140 mmHg and/or

diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is ≥90 mmHg [4].

Uncontrolled elevated BP contributes to kidney failure and

blindness. It significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular

diseases such as heart attack and stroke in hypertensive or prehypertensive

patients [5]. However, most individuals with prehypertension

or hypertension are not aware of the seriousness

of elevated BP, they often continue their lifestyle habits such

as unhealthy diet intake, lack of physical exercise, alcohol

consumption, and smoking. Many of the patients with hypertension

do not comply with their prescribed antihypertensive drug regimen

and/or follow-up medical visits, which increases their risk of

cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [6-8]. Antihypertensive

drugs are commonly prescribed to control high BP. However, many

patients have been reported to neglect their medication regimen

or even discontinue medication due to adverse effects or the high

cost of medicine [2,9]. In addition to antihypertensive medication

use, lifestyle modification approaches such as reduced sodium

intake, increased physical activity, and reduced body weight

are recommended [1,10]. However, such modifications require

persistent compliance and motivation [1,11-14].

Under stressful situations, our body releases stress hormones

into the bloodstream. This causes a rise in heart rate (HR) and BP

[15]. BP consistently increases after an extended period of stress.

Therefore, stress reduction is another effective way to control

hypertension [16]. Forest bathing (FB) or “Shinrin-yoku” was first

defined by Japanese and observed to have therapeutic effects after

spending time in nature or in a forest area [17]. The term “forest

therapy” was recently developed regarding its clinical efficacy of

exposure to a forest environment [18]. “Forest bathing” and “Forest

therapy” are used interchangeably in this study. FB refers to visiting

the forest environment or taking in the forest atmosphere to slow a

person’s pace of life [17,18]. The individual is guided to connect with

the natural environment using their five senses to achieve healing.

This includes increasing the natural killer cell activity to prevent

tumor growth, enhancing immune function to facilitate recovery

from illness, increasing the feeling of relaxation, and relieving

stress, promoting restorative effects and positive mood as well as

improving cognitive function on creativity [19-25]. FB promotes

relaxation by inducing the activity of the parasympathetic nervous

system, which decrease BP and HR [18,25,26].

Several studies have reported a positive association between

FB and a reduction in BP and HR in patients with prehypertension

and hypertension [27-39]. A review of these studies reported that

visits to a forest environment could increase the activities of the

parasympathetic nervous system and decrease the production of

stress hormones. This, in turn, induces physiological and mental

relaxation [40]. Another review study identified that practicing

a 2-hour single forest walk, or one-day FB program could obtain

short term physiological and/or psychological benefits on health

[41]. Participants exhibited a significantly improve in the positive

emotions and decreased in the negative emotions of tension,

anxiety, fatigue, depression, confusion, and anger after practicing

a single four-hour FB program, as measured by the Profile of Mood

States (POMS) [31,37,38].

In addition to FB, the practice of slow diaphragmatic deep

breathing exercise (DDBE) is also reported to be an effective

relaxation method for improving both physiological and

psychological health in hypertensive adults, as it stimulates the

activity of the parasympathetic nervous system [42,43]. The

therapeutic effects of DDBE have long been reported regarding

lowering of BP in hypertensive adults [44,45] and reducing stress

and depression in healthy adults [42]. In DDBE, people take a deep

breath and slowly release their breath rhythmically through the

contraction of the diaphragm to minimize respiration frequency

and maximize the amount of oxygen entering the bloodstream

[42,46]. DDBE at six breaths/minute can lead to vasodilation of

arterioles by triggering pulmonary-cardiac mechanoreceptors

and suppressing the sympathetic nerve activity and activating

chemoreflex. This increases baroreflex sensitivity, resulting in the

reduction in SBP and DBP as well as increased HR variability [43-

49]. Practicing regular slow DDBE is reported to stimulate the vagal

nerve, leading to the regulation of emotion in adults [42]. A review

literature recently identified that practicing DDBE at six breaths

per minute for 2 minutes, or practicing 10 minutes of DDBE twice a

week, or twice a day for four weeks, significantly reduced SBP and

DBP in hypertensive individuals [50]. Another study reported that

20 sessions of 15-minute slow DDBE on every second weekday over

a period of eight weeks could trigger relaxation responses. This

effect demonstrated an improvement in sustained attention, affect,

and reduction in stress [42].

Forest bathing has not been tested as clinical practice guideline

on hypertension [51]. Although FB offers psychological and

physiological health benefits, most studies have focused either on

the emotional benefits or on physiological effects [30,32,33,35,37].

Only a few studies examined the sustained effects on physical

responses or on both emotion and physical responses of FB [36,37].

However, the results are inconsistent in that while one study

reported that after a one-day forest therapy program, the effect on

lowering BP can lasted for five days [37], while another found that

the decrease in BP could be sustained for eight weeks after a threeday

forest therapy program [36]. The current data of the therapeutic

effects of FB is insufficient to establish clinical guidelines for use

in disease prevention. To facilitate evidence-based clinical practice

guidelines for health professionals for the use of such therapy, it

is essential to examine the potential benefits of FB. Evidence of

the effects of FB regarding the management of hypertension can

be strengthened if a comparison can be made with DDBE. The

DDBE approach has established beneficial effects on reducing BP

and stress levels in adults [42,43,44]. DDBE is recommended and

adopted as stress management for these patients in Hong Kong

[52]. Some outpatient clinics offer DDBE sessions for such patients

who suffered from mood disturbance [53].

Based on the protocol adopted in previous studies, this study

measured and compared the psychological and physiological

benefits of FB and DDBE over a period of four weeks and examined

the sustained effect of both interventions for eight weeks after the

intervention [31,36,42,45,50]. The findings of this study provided

preliminary evidence that FB is more effective than DDBE in

lowering SBP and anxiety levels in the study population. This study

aimed to (1) examine the effects of a four-week FB intervention (2)

examine the effects of a four-week DDBE intervention; (3) compare

the differences of effects between FB and DDBE; and (4) compare

the sustained effect of FB and DDBE, on SBP, DBP, PR, state and trait

anxiety level, and mood status of participants.

Materials and Method

Study design

This was a quasi-experimental feasibility study. Eligible participants underwent either FB or DDBE intervention after matching the baseline characteristics of the participants. Considering the preference and feasibility of actual participation in the program, eligible participants could choose to join either the FB or DDBE group.

Participants and selection criteria

Participants were community-dwelling adults with prehypertension or hypertension. They were recruited from Shinrin- Yoku Hong Kong, an association that offers unique guided forest therapy to community dwellers, and from the Federation of Alumni Associations of a large local university. An invitation poster was displayed on the Facebook page of Shinrin-Yoku Hong Kong and on the network of the alumni associations in April and May 2020 to recruit potential participants who showed interest in the program. Potential participants were screened for BP and their health history was assessed by completing an online demographic questionnaire to determine eligibility. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) men or women aged between 45 and 64 years; (2) living in Hong Kong and able to read Chinese and understand Cantonese (the dialect used in Hong Kong), (3) SBP consistently ranging from 120 to 159 mmHg and/or DBP ranging from 80 to 100 mmHg, (4) not taking any antihypertensive medication, and (5) did not receive relaxation therapies for the past two months, including forest therapy. The participants with extremely high SBP above 159 mmHg were considered inappropriate to be included in the intervention and were advised to seek medical care. Those who were pregnant or experienced chronic pain and muscle weakness, were unable to walk independently, were diagnosed with coronary heart disease, stroke, carcinoma, or known mental disorders such as delusions and depression; and undergoing psychotherapy were excluded.

Sampling and sample size estimation

Based on the result of a RCT study [36], participants who received FB had reduction in SBP (n=56; -12+/-9.2) in compared to participants who received DDBE (n=56; -3.5+/-9.2). The sample size was calculated based on F test using G*Power 3.1.9.4 statistical software [54]. This provided a 5% level of significance (twotailed test) of the effects among two interventions on the primary outcome of participants (i.e., reduction on SBP), with a power of 80%, approximately 10% of attrition, 1:1 ratio of intervention and control group, the estimated sample size would be 22 participants per arm with a total of 44 participants would be required [55].

Intervention and control

Participants in both intervention and control groups were asked to perform normal life activities on the days before participating in the interventions. They were instructed not to take alcoholic and caffeine drinking, smoking and not to do strenuous physical activity 30 minutes before and during the intervention sessions.

Forest bathing intervention

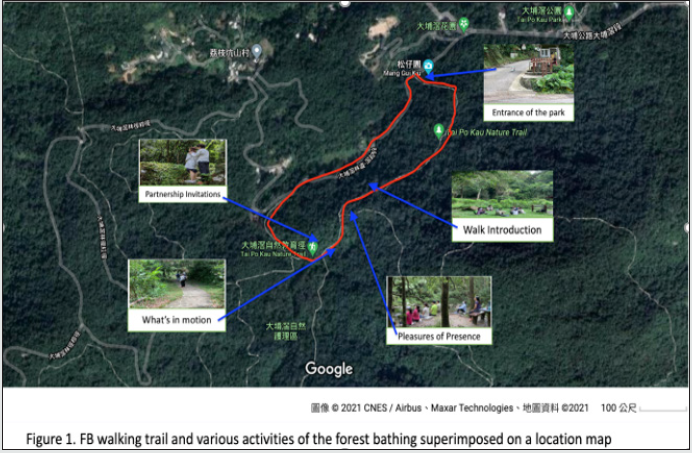

FB was used as the study intervention procedure. Participants

received four 2-hour forest therapy sessions for four consecutive

weekends in a country park in Tai Po Kau Nature Reserve. Tai Po

Kau Nature Reserve, a secondary forest, was located on the Tai

Po area of the New Territories in northern Hong Kong. It was reestablished

by Hong Kong government since 1946. The area covered

440 hectares of long-established forestry plantations with more

than 100 different species of trees canopy reaching heights of 18-

22m, including Camphor Tre, China Fir, Taiwan Acacia and Paperbark

Tree and the dominant tree was Chinese Red Pin [56,57]. The

altitude of the forest area is 300m with plantations extended from

the eastern slopes of grassy Hill down to Tai Po Road, the mean

annual temperature and relative humidity of the nature reserve is

22.9 °C and 78.7%, respectively, wet seasons were marked between

March and October [57]. On all days that FB interventions occurred,

the weather included sunny, cloudy, or drizzling conditions with

average air temperatures ranging from 24.5°C to 32.5°C and relative

humidity ranging from 64% to 94%.

Four consecutive forest therapy sessions were conducted in the

daytime on Saturdays between May and July 2020. Participants were

divided into four groups (A–D), and each group had five to seven

participants. Participants in group A received four consecutive

sessions of therapy at 10:00 on May 9, 16, and 23 and at 14:00 on

June 14, 2020. Participants in group B received four consecutive

forest therapy sessions at 14:00 on May 9, 16, and 23 and at 14:00 on

June 14, 2020. The fourth session of forest therapy for groups A and

B, which was originally scheduled on May 30, 2020, was postponed

to June 14, 2020, due to thunder and heavy rainstorm warning

signals that were raised on May 30, 2020, and June 6, 2020. A third

local storm warning signal was also raised at 12:00 pm on June

13, 2020. Participants in groups C and D received four consecutive

sessions of therapy at 10:00 and 14:00, respectively, on June 20 and

27 and on July 4 and 11, 2020. The total distance we covered for

each visit was less than 2 km with altitude of 100-200m; the average

walking speed was around 1km/h and the slope of walking is less

than 5%. On the day of the intervention, participants gathered at

the entrance of the country park. They received a 5-minute briefing

regarding the intervention. A researcher, who is a qualified nurse,

was responsible for data collection before the briefing, providing

briefing, and maintaining the consistency of the interventions at all

sessions. The qualified forest therapy guide from the Association

of Nature & Forest Therapy, with wilderness first aid certificate,

was responsible for facilitating safe and gentle walks and providing

instructions for sensory activities along the way in all the sessions.

After the briefing, the participants first took a 15-minute walk to

an area where there was a nearby stream. FB guide then began the

FB intervention by a set of experiential thresholds, called Standard

Sequence [58]. Drew on the theoretical framework of liminality, this

sequence includes four invitations to facilitate participants’ deeper

connection to the nature [59]. First, participants were invited to

slow down and remain in the sitting or standing position. They were

encouraged to share previous experiences with the forest for 20

minutes (1st invitation: walk introduction). They were then invited

to close their eyes and awaken their sense of listening, to breathe

in, and to sample the air and open their eyes to see the natural

environment for another 20 minutes (2nd invitation: Pleasure of

Presence). Participants then wandered to the designed forest path for another 20 minutes to slow down both physically and mentally

(3rd invitation: What’s in motion). Finally, they were invited to

spend 20 more minutes strolling around the designed path, and

they were encouraged to look for or touch the surrounding natural

materials to build a deep connection with nature (4th invitation:

Partnership invitation). Participants were given approximately 20

minutes of rest and sharing time between each activity change. The

Tea Ceremony, as second threshold, was incorporated at the end

of the intervention to allow the participants to appreciate what

the forest was offering in that moment. They were then allowed to

leave the country park individually (Figure 1).

Diaphragmatic deep breathing exercise intervention as control

DDBE was adopted as the control intervention. Participants were divided into two groups, with six to seven participants in each group. Four sessions of DDBE were conducted on four consecutive weekends from June 14 to July 5, 2020, to compare its therapeutic effect with FB. Each session lasted for 1 hour and was conducted during the morning (10am-11am) on weekends. In the first session, participants performed guided deep breathing in a quiet room at the College where the first researcher work at room temperature ranging from 25°C to 28°C. During the 1-hour DDBE intervention, participants were invited to first rest for 20 minutes to adapt to the environment. A qualified counselor demonstrated the DDBE technique for 10 minutes. Participants were then required to return the demonstration under the qualified counselor’s monitoring until they reported having good control of the breathing rate using the technique. Participants were asked to sit comfortably with closed eyes, and they were guided to breathe deeply through the nose at a rate of six breaths/minute for 15 minutes followed by 5 minutes of normal breathing under the direction and supervision of the qualified counselor. They were instructed to place one hand below their rib cage and to inhale as deeply as they could while their stomach moved out against their hand. They were taught to inhale through both their nostrils slowly up to their maximum for four seconds and to exhale slowly through the mouth up to their maximum for approximately 6 seconds. Subsequently, they were taught to exhale as slowly, as they could by tightening their stomach muscles; however, the upper chest was to remain as still as possible. Participants were provided with written instructions to practice 10 minutes of DDBE every morning and evening at home in a quiet room for four weeks after the first DDBE session. In each session, they were asked whether they practiced DDBE in a timely manner and were encouraged to share their difficulties with the practice of DDBE. They were required to document the starting and ending time of each breathing practice session on a practice log sheet and return the completed practice log sheet to the researcher after completing the intervention.

Methods of assessment

The primary outcome measures of this study were blood pressure (i.e., SBP, DBP). The secondary outcomes were PR, mood state and anxiety level. BP and PR were measured using a validated portable digital sphygmomanometer at baseline assessment (by self-measurement at home), before and immediately after each intervention and eight weeks after intervention. Participants were instructed to sit quietly for 5 minutes before measurement to stabilize SBP, and then a standard brachial cuff was wrapped evenly and firmly around the participant’s upper forearm. SBP and DBP (mmHg) and PR (beats/minute) were obtained from two measurements in a seated position. The two measurements had an interval of at least 30 seconds, and the average value of the two readings was recorded [52]. Mood state was measured using the Chinese version of the POMS-Short Form (POMS-SF). Mood state refers to the assessment of heightened musculoskeletal tension (tension-anxiety), mood of depression followed by a sense of personal inadequacy (depression-dejection), mood of anger and antipathy to others (anger-hostility), a mood of vigorousness and high energy (vigor-activity), mood of wariness and low-energy level (fatigue-inertia), and confusion and discomfort (confusionbewilderment) [60]. Anxiety levels were measured using the Chinese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (C-STAI) questionnaire. Anxiety was defined as feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and increased BP [61].

Questionnaires and their validity and reliability

The questionnaires for this study were compiled and included the following: (1) a demographic questionnaire, (2) the C-POMS-SF questionnaire, and (3) the C-STAI questionnaire.

Demographic questionnaire

A set of questions were established to collect data on participants’ demographic characteristics and lifestyle behavior during the preliminary BP screening and health history assessment. The questionnaire consisted of ten questions. The first four questions were designed to collect data regarding demographic variables including age, sex, level of education, and body mass index. Four questions inquired about the participants’ lifestyle behavior, including the frequency of alcohol consumption and smoking history as well as the time spent on physical exercise. The last two questions were about medical history and antihypertensive medication intake. All demographic characteristics were used to determine eligibility. This demographic questionnaire was administered in both English and Chinese and reviewed by a panel of reviewers.

Chinese version of the Profile of Mood States Short Form (POMS-SF) questionnaire

POMS-SF is an established self-reporting questionnaire which consists of 30 adjectives describing feelings and moods that participants experienced during the past week [60]. It measures six dimensions of mood: tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, fatigueinertia, anger hostility, confusion-bewilderment, and vigor-activity to assess the participants’ various mood changes. The five-point Likert scale ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) for each item. The total mood disturbance score was obtained by summing the sores on five scales of tension: anxiety, depression-dejection, angerhostility, fatigue-inertia, and confusion-bewilderment (a constant of +4 is added to the total score of the confusion-bewilderment scale to eliminate the negative score) and subtracting the score of vigor-activity from the total scores. The higher the score is, the higher the level of mood disturbance [60,62]. The English version of the POMS-SF has been widely used in elderly populations and after surgery, with higher alpha coefficients ranging from 0.73 to 0.89, in the study of 102 non-disabled community elders [60,63]. The Chinese version of the POMS-SF had higher alpha coefficients ranging from 0.98 to 0.99 in the six mood states [62,64].

Chinese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (C-STAI) questionnaire

Anxiety levels were measured using the C-STAI questionnaire. STAI is an established self-evaluation questionnaire designed to assess individual state and trait anxiety. It consists of 40 items in which 20 items each measure state and trait anxiety [65]. Both state and trait subscales were assessed using a four-point Likert scale, from 1 for “not at all” to 4 for “very much so” for the trait anxiety factor, and from 1 for “almost never” to 4 for “almost always” for the state anxiety factor. The score ranged between 20 and 80. The higher the score is, the greater the anxiety level [65]. A study reported that the STAI questionnaire has good reliability and moderate validity regarding depression assessment [66]. The STAI has been used widely and extensively in research and clinical settings, with high alpha coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.95 [67]. The C-STAI possessed a high Cronbach’s alpha of validity and reliability ranging from 0.90 to 0.81 [68], and it is widely used to examine psychological stress recovery after FB, psychological distress with cancer pain, and myocardial infarction distress [31,69,70].

Method of data collection

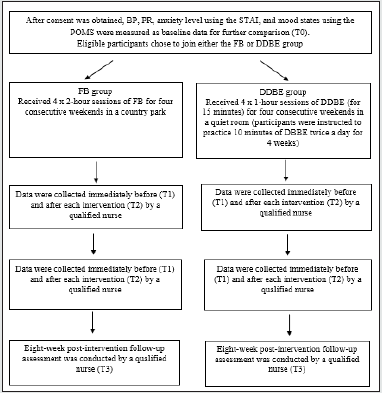

The outcomes were measured from May to July 2020 at four points during the study: baseline assessment (T0), immediately before (average of T1), and after each of FB and DDBE session (average of T2), and eight weeks after the completion of both interventions (T3). The baseline assessment was conducted to determine potential participants’ eligibility, including their BP, age, medical history, and number of prescribed antihypertensive drugs. The eligible participants were given an explanation and an information sheet regarding the study and its aim, using an online form. After obtaining consent, the participants’ BP and pulse were measured as baseline data by self-measuring at home following the steps on the information sheet for BP measurement. Participants were instructed to measure BP and pulse according to the steps on the information sheet and reported the related readings to researcher accordingly. Information on anxiety levels was collected using the STAI and mood states through the POMS-SF, presented both in English and in Chinese, respectively, using an online form as baseline data for further comparisons. Throughout the study period, all data were collected by a qualified nurse. Outcome measures including BP, PR, level of anxiety, and mood states were collected immediately before and after each session of FB and DDBE. No measure could be obtained while participants completed a four-week self-practice of DDBE at home. However, participants were contacted to measure their BP in the morning and complete the online version of the STAI and POMS-SF that was offered both in English and in Chinese on the weekend of the twelfth week for the post-eight-week intervention follow-up assessment. The timeline of the interventions and outcome measures over the 12-week study period is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the timeline of interventions and outcome measures over the 12-week study periods.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, Version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). Multiple imputation approaches were used to impute the missing values of the dataset. Data were initially analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. When the data were normally distributed, a paired t-test was used to test for significant differences of the outcomes within the two groups and unpaired t-test was used to compare the mean difference between the two groups. When data were ordinal, the Pearson chi-square test was used to compare the significant difference of outcomes between the two groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). For all comparisons, effect size was reported using Cohen’s and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-committee (HSEARS2020123006) and the Clinical Research Ethics Sub-committee of the University where the study was conducted (CRESC202002). Participants in both interventions were provided with information sheets and were fully informed about the aims and procedures of the study as well as the benefits and risks of study participation. Written consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, and they could withdraw from the study at any time without negative consequences. Data collected were anonymous and kept confidential.

Results

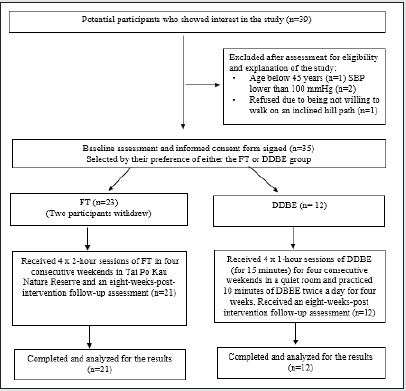

This intervention and outcome measures lasted for 12 weeks, from May 2020 to August 2020. Potential participants responded to the online demographic questionnaire for eligibility screening. A total of 23 participants participated in the FB intervention, with 11 starting in the four consecutive sessions of forest therapy in May 2020 and the other 12 starting in June 2020. Due to personal issues, two participants in the forest therapy group withdrew from the study two days before the therapy began. Additionally, 12 participants chose to join the DDBE group to receive DDBE training. Therefore, this study comprised 33 participants. Figure 3 shows the flowchart of the participant selection process in the study.

The compliance rate was good. Participants in the DDBE group completed 100% of the four consecutive sessions, with 90% practicing DDBE twice a day at home. In contrast, participants in the forest therapy group completed 87% of the four consecutive sessions. The missing values of individual participant were identified using multiple imputation approach. After five times of imputation, the missing values were replaced by random sample. No adverse events were reported by participants in either group during the intervention period.

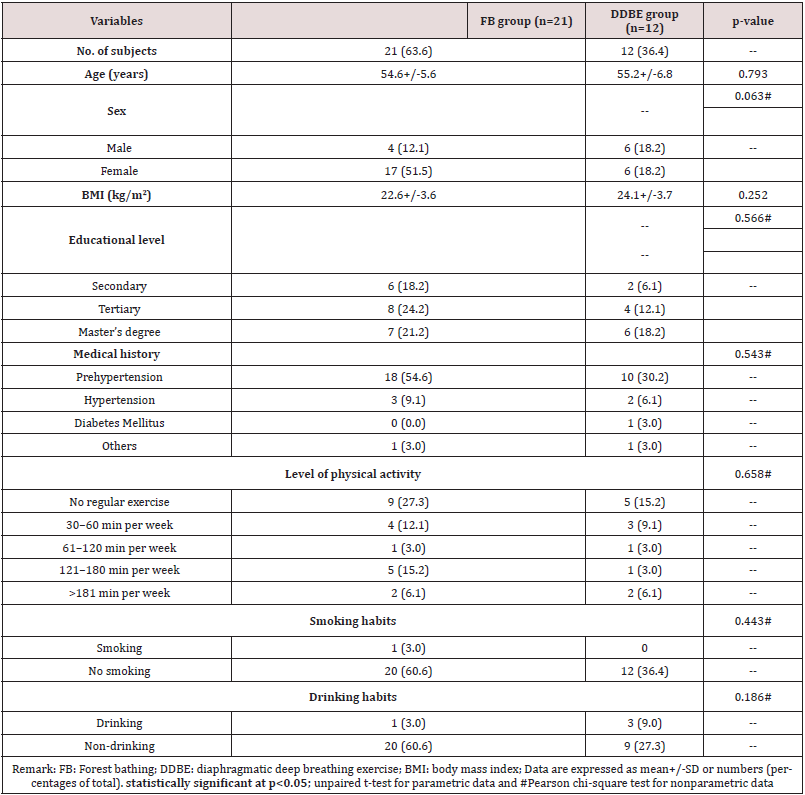

Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of participants in FB and DDBE intervention groups at baseline

Table 1 shows the demographic data of participants in each group in terms of age, sex, education, BMI, disease history and the lifestyle characteristics of participants including level of physical activity, smoking, and drinking habits. The mean ages of the FB and DDBE groups were 54.6±5.6 and 55.2±6.8 years, respectively, without significant difference between the two groups. The proportion of females was higher in the FB group, and the mean BMI of the DDBE group was 2.1 kg/m2 higher than that of the FB group. Almost half of the participants in both groups had university degrees or higher levels of education, and no significant difference in education levels was observed between the two groups. Although 54.6% and 30.2% of participants in the FB and DDBE groups, respectively, were reported to be pre-hypertensive, there was no significant mean difference. Approximately 45.5% and 27.3% of participants in the FB and DDBE groups, respectively, reported not practicing relaxation techniques for stress relief. In addition, 27.3% and 15.2% of participants in the FB and DDBE groups, respectively, reported not performing regular physical exercise, while 21.3% and 9.1%, respectively, performed physical exercise ≥150 minutes per week. Further, 60.6% of participants in both groups reported no smoking or drinking habits. No significant difference was observed in smoking and drinking habits.

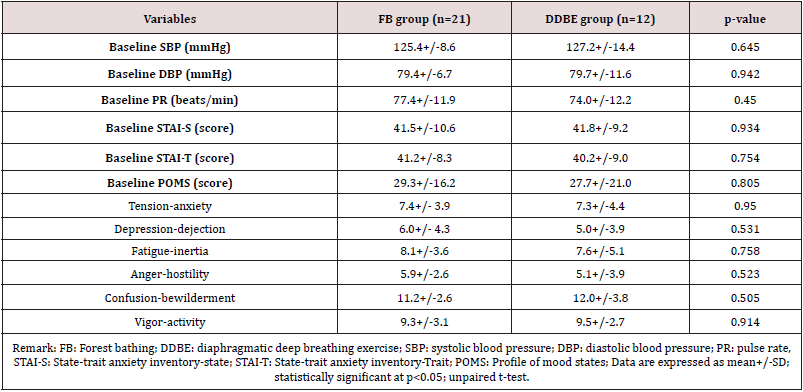

Table 2 shows a comparison of SBP, DBP, PR, anxiety level, and mood states of participants between the two groups at baseline. The comparison showed that the mean values of SBP, DBP, PR, anxiety level, and mood states of participants were similar between the groups. There were no significant differences in the physiological and psychological indicators of participants between the two groups at baseline (p>0.05).

Effects of FB and DDBE interventions and their differences

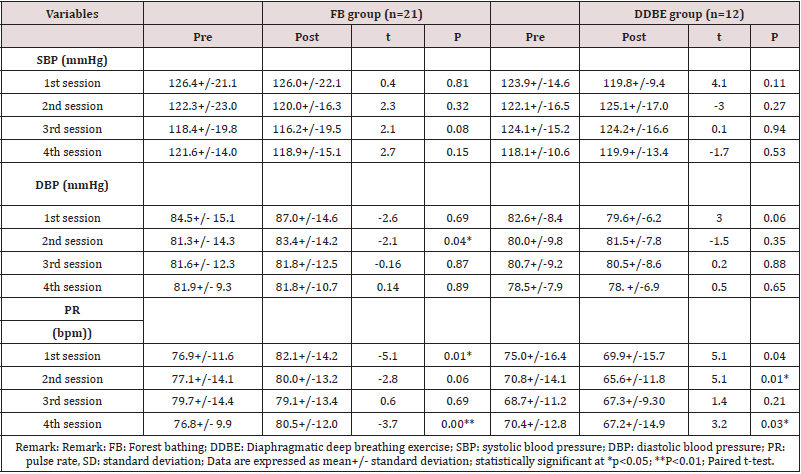

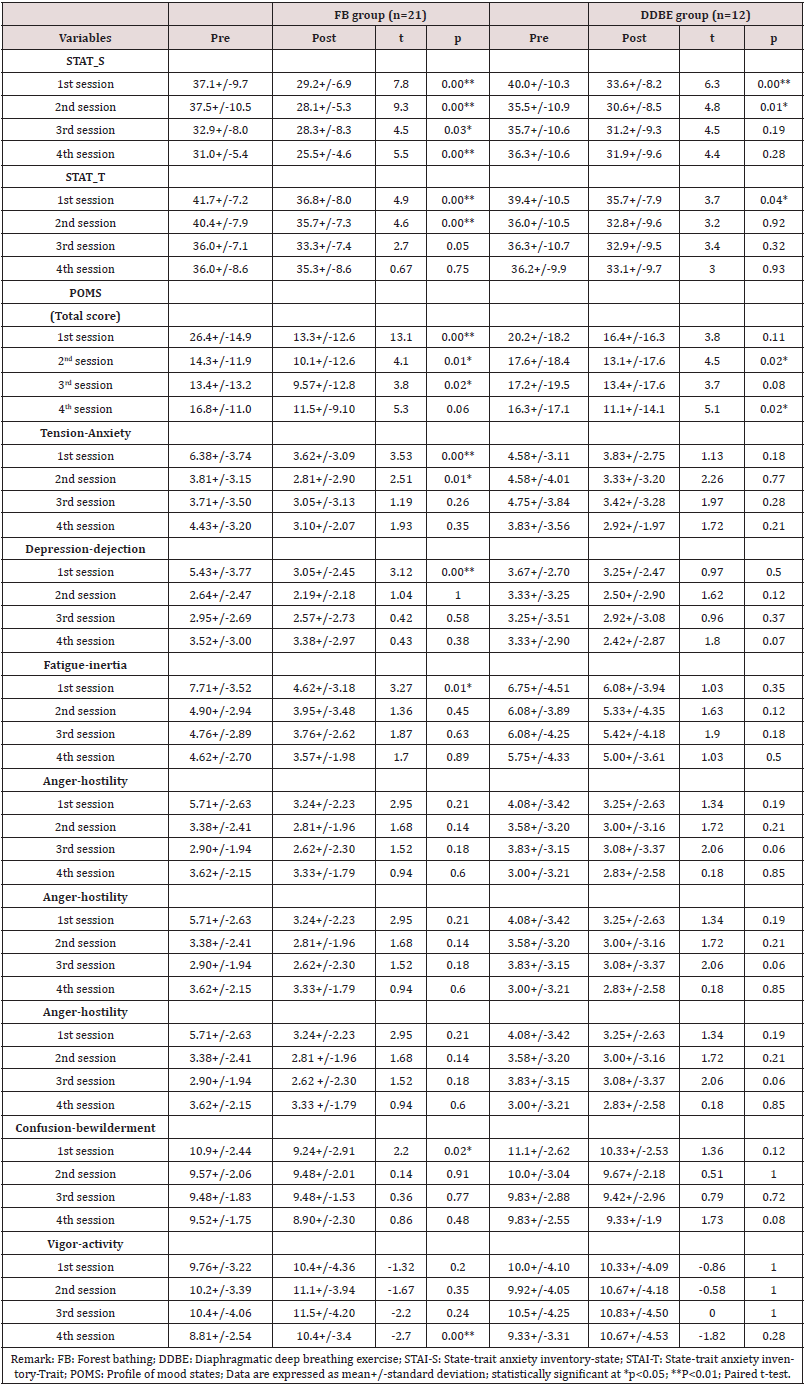

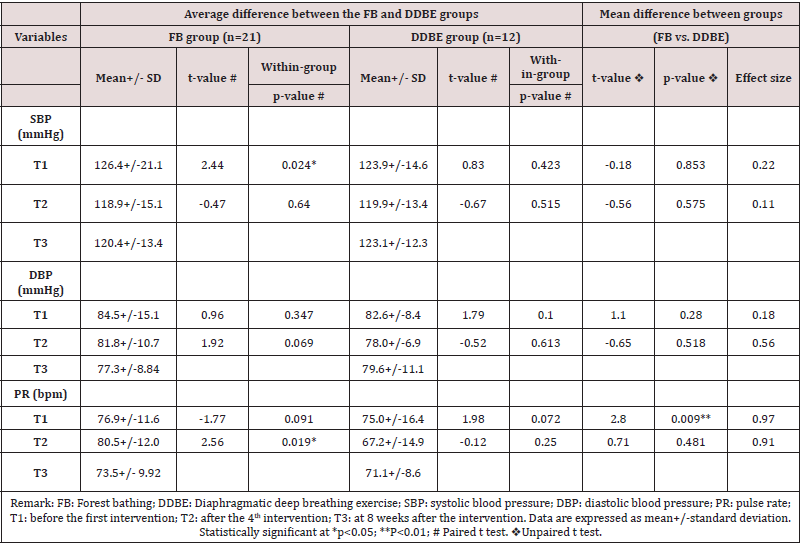

The physiological and psychological effects of FB and DDBE on participants were examined and compared after each session; the results were shown in Table 3 and 4, respectively. Data were analyzed using paired t-test and unpaired t-test.

Effects of FB and DDBE interventions on systolic and diastolic blood pressure and their differences

Table 5 showed that, after four weeks of FB intervention

(from T1 to T2), there was a decrease of 7.4 mmHg in SBP (t=

2.44; p=0.024), but no significant effect of the DDBE on SBP

(t=0.83, p=0.423). There was no significant effect of FB and

DDBE interventions on DBP (t=0.96, p=0.347 & t=1.79, p=0.100,

respectively). There is no significant difference between the effects

of FB and DDBE interventions on SBP (t=-0.18, p=0.853) and DBP (t=1.10, p=0.280). The results showed no significant effects of the

four weeks of FB on PR (t= -1.77; p=0.091). However, a comparison

of the effects between the FB and DDBE group interventions on PR

showed that there was a significant difference (t=2.80, p=0.009),

with a decreased of PR by 7.7 beats/minute (t=1.98, p=0.072) after

the DDBE intervention.

The sustained effects of FB and DDBE on BP and PR were

examined and compared between T2 and T3 using an unpaired

t-test (Table 5). The results showed that, at eight weeks after the

intervention, there were no significant sustained effects of FB and

DDBE on SBP and DBP (p>0.05). However, there was a decrease

of 6.9 beats/minute in PR at eight weeks after the FB intervention

(t=2.56; p=0.01). Contrarily, there was no significant sustained effect

of DDBE intervention on PR (t=-0.12, p=0.25). A comparison of the

sustained effects between the FB and DDBE group interventions on

SBP, DBP and PR showed no significant difference (p>0.05).

Table 5: Comparison of the physiological effects of FB and DDBE after 4 weeks of intervention (from T1 toT2) & at 8 weeks post intervention (from T2 to T3)

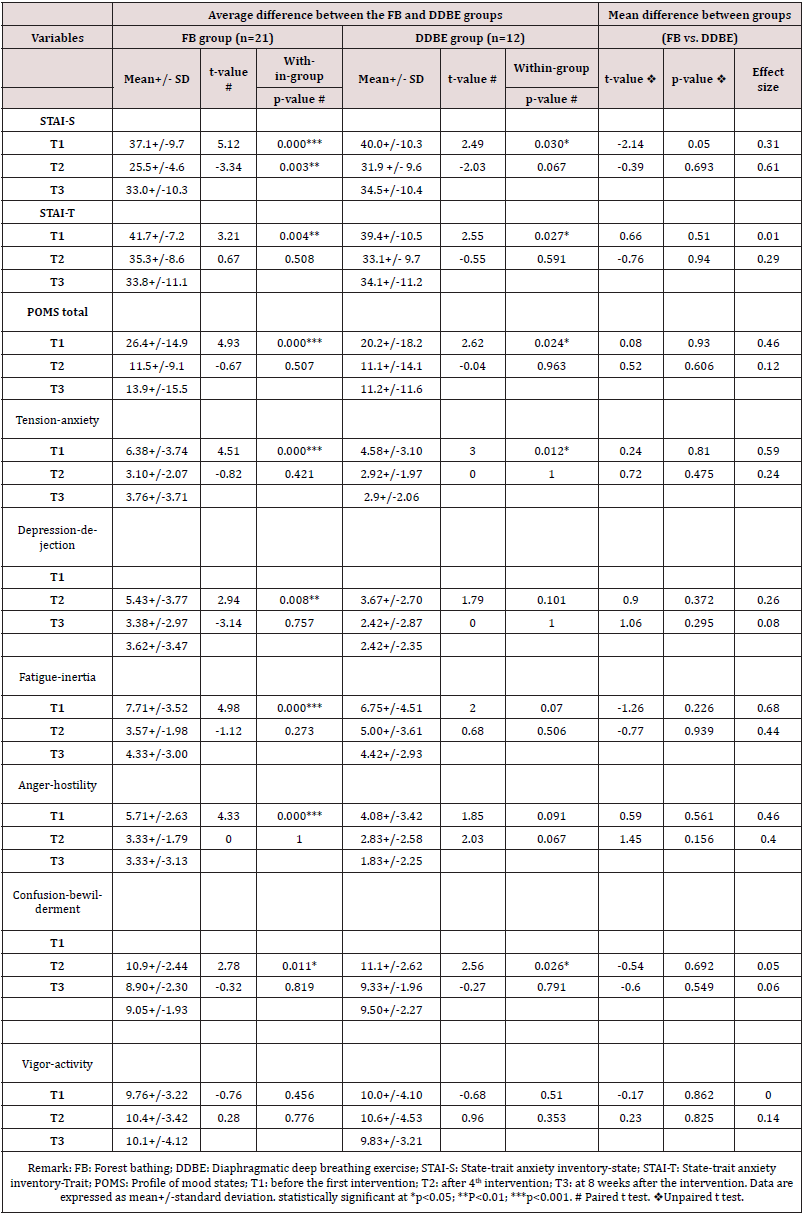

The psychological Effects of FB and DDBE interventions on the anxiety level in terms of STAI-S and STAI-T, mood states in term of POMS and their differences

Table 6 showed that, after four weeks of the FB intervention, there was a decrease of 11.5 in the STAI-S score (t=5.12; p=0.000) and 6.4 in the STAI-T score (t=3.21, p=0.004). In addition, the DDBE intervention had a significant effect on state and trait anxiety level in terms of the STAI-S and STAI-T scores, which decreased by 8.0 (t=2.49, p=0.030) and 6.2 (t=2.55, p=0.027), respectively. A comparison of the effects between the FB and DDBE group interventions on the STAI-S score almost showed a significant difference (t=-2.147, p=0.05) but the comparison showed no significant differences on the STAI-T score (t=0.66, p=0.51). The results also showed that, after four weeks of FB and DDBE interventions, there was a significant decrease in total POMS scores by 14.8 (t=4.93; p=0.000) and 9.0 (t=2.62, p=0.024), respectively. Comparison of the effects between FB and DDBE group interventions on POMS total showed no significant differences (t=- 0.089, p=0.930). Of the effects of negative moods, as the analysis showed, after four weeks of the FB intervention, tension-anxiety and confusion scores decreased by 3.28 (t=4.51; p=0.000) and 2.0 (t=2.78; p=0.011), respectively. There were also significant effects of the four weeks of DDBE intervention on the score of tensionanxiety and confusion, which decreased by 1.66 (t=3.0, p=0.012) and 1.83 (t=2.56, p=0.026) respectively.

Table 6: Comparison of the psychological effects of FB and DDBE after 4 weeks of intervention (from T1 toT2) & at 8 weeks post intervention (from T2 to T3)

The results also showed that after four weeks of the FB intervention, there was a decrease in the scores of depressions, fatigue, and anger by 2.0 (t=2.94; p=0.008), 4.1 (t=4.98; p=0.000) and 2.3 (t=4.33; p=0.000), respectively. However, there were no significant effects of four weeks of the DDBE intervention on the scores of depressions, fatigue, and anger (p>0.05). A comparison of the effects between the FB and DDBE group interventions did not show significant differences on tension anxiety, depression, fatigue, anger, and confusion (p>0.05). Of the effects of positive mood, there were no significant effects of the four-week FB and DDBE interventions on the vigor activity score (t=-0.76, p=0.456 & t=- 0.68; p=0.510, respectively). A comparison of the effects between the FB and DDBE group interventions showed no significant differences in vigor activity (t=-0.17, p=0.862). At eight weeks after FB intervention (from T2 to T3), there was a significant increase in the STAI-S score by 7.4 (t=-3.34; p=0.003). However, there was no significant effect of DDBE intervention on the STAI-S score (t=- 2.03, p=0.067). There were no significant sustained effects of FB and DDBE interventions on the STAI-T score, total POMS score, all negative and positive feelings of mood from T2 to T3 (p>0.05). A comparison of the effects between the FB and DDBE group interventions on the score of STAI-S, STAI-T, total POMS, tensionanxiety, depression, fatigue, anger, confusion, and vigor activity showed no significant difference (p>0.05).

Discussion

This study is the first to examine and compare the effectiveness of FB and DDBE in middle-aged adults with pre-hypertension and hypertension in Hong Kong. The results of this study provide preliminary evidence for an association between FB and DDBE regarding changes in BP, PR, anxiety, and mood states in prehypertensive and hypertensive middle-aged adults.

Effects of forest bathing and diaphragmatic deep breathing exercise on blood pressure

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in

SBP and DBP after a two-hour single forest walk [31] and a six-hour

single FB program [37] in middle-aged adults with pre-hypertension

and hypertension. In this study, the mean SBP significantly

decreased by 7.4 mmHg after completing four consecutive sessions

of FB in four consecutive weeks (t=2.44; p=0.024), but there was

no statistically significant decrease in DBP after the intervention.

The results of BP in this study were not consistent with those of

previous studies. Because blood pressure has a diurnal variation

rhythm, it will be higher in the morning and lower in the afternoon.

Therefore, it is desirable to compare the blood pressure at the same

time on different days.28 Considering that the BP of FB groups

were not measured at the same time on the different intervention

days, the comparison of blood pressure before and after walking

within FB groups may be affected due to diurnal variation rhythm.

The blood pressure could only be compared after four weeks of

interventions, i.e., FB versus DDBE in the morning. In the present

study, although there was a reduction in BP after completing four

consecutive FB sessions, practicing four consecutive sessions of FB

in four consecutive weeks were not found to be more effective in

lowering blood pressure than that of DDBE. It may be influenced by

diurnal variation rhythm. Besides, high salt and calorie consumed

may increase individual blood pressure [56]. We did not monitor

and compare the changes in calorie and salt intake of participants

during the intervention periods, the lowering effect of FB and DDBE

on blood pressure may be underestimated in this study. Due to

heavy rainstorm warning, the fourth session of FB was delayed by

two weeks. The SBP of these participants after the fourth session

was higher than that those after the third session. A positive

association between lowering SBP and four sessions of two-hour

FB for four consecutive weeks was observed in middle-aged prehypertensive

and hypertensive adults.

In addition, two previous studies revealed that 10-minute

voluntary DDBE at 6 breaths/minute daily or twice a day for four

weeks could reduce SBP and DBP in pre-hypertensive participants

[49,71]. The results of this study were not consistent with those of

previous similar studies on BP changes after DDBE. A significant

reduction in SBP and DBP was not observed in the DDBE group

during the intervention period. In this study, four sessions of 15

minutes of DDBE for four consecutive weeks with 10 minutes of

self-practice of DDBE twice a day for four weeks was not associated

with lowering SBP or DBP. Short-term DDBE was not found to be

effective in contributing to cardiovascular health. Compared with

DDBE, FB demonstrated a potential therapeutic effect on lowering

SBP in middle-aged pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults. This study suggests that visits to forest areas on four consecutive

weekends show more beneficial cardiovascular effects than

practicing DDBE in a quiet room.

Effects of forest bathing and diaphragmatic deep breathing exercise on pulse rate

PR was used as a physiological indicator of response to the environment. Visiting forest environments had a relaxing effect and lowered the PR by 5%–6% and contributed to the cardiovascular health of hypertensive adults [28,30]. In this study, PR in the FB group was increased without any significant difference (t=-3.57, p=0.09) after the completion of four consecutive FB sessions. It is not surprising that the PR increased immediately after the FB intervention because FB is an outdoor activity required low intensity level of physical exercise. The rising of PR of FB group may be caused by the distances of walking and hot weather. In contrast, PR in the DDBE group decreased gradually during the intervention period. DDBE significantly reduced PR by 7.7 beats/minute after the intervention periods. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that regular practice of DDBE at six breaths/ minute could reduce PR in both pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults after a four-week intervention [48,71,72]. Comparing the mean PR values between FB and DDBE, the mean value of PR in the DDBE group was progressive and significantly decreased over the four sessions. Since DDBE is an indoor intervention in which participants were not required either standing or walking, while FB is an outdoor activity required short distance of slow walking, the lowering effect of PR of FB and DDBE group might be affected due to the different physical level required between the two interventions. Nevertheless, this study suggests that DDBE has potential beneficial effects on cardiovascular health by lowering heart rate.

Effects of FB and DDBE on the anxiety level and mood states

In addition to the physiological beneficial effects, FB and DDBE were associated with beneficial psychological effects on enhancing positive mood and reducing anxiety. Visits to a forest environment have been reported to have a stress-relieving effect on pre-hypertensive and hypertensive individuals [29,31]. DDBE was also found to have a significant correlation with reduced anxiety levels after a two-week regular DDBE intervention among hypertensive adults [72]. Consistent with previous studies, the results of this study indicated that FB and DDBP could reduce state and trait anxiety levels among participants. Evidence from this study showed that FB was more effective in reducing state anxiety than DDBE. Compared with DDBE, FB had a more positive relaxing effect on decreasing anxiety levels among pre-hypertensive and hypertensive middle-aged adults. A significant reduction in state and trait anxiety levels was first observed in participants after the four-week DDBE intervention. The results provide clinical evidence to healthcare providers of the use of such a relaxation approach as part of the initial treatment of pre-hypertension and hypertension. The results of this study showed that mood states measured using the POMS subscales were significantly improved after the four-week FB intervention. Several previous field studies reported that positive moods were significantly increased, and the negative moods were significantly decreased by forest visits [27,29,31,38]. These results were not completely consistent with those of previous field studies. In this study, a significant decrease in the scores of total mood states and negative feelings, including tension-anxiety, fatigue, anger, depression, and confusion, was observed after the completion of four sessions of 2-hour FB. However, there was no significant change in positive feelings of vigor after the intervention. The results of this study also found a significant reduction in the feelings of tension-anxiety and confusion after completing the four-week DDBE intervention. The lowering effects on the negative feelings of tension-anxiety and confusion of participants were first observed after completing the four DDBE sessions. In addition, there was no significant change in the positive feelings of vigor after the four-week DDBE intervention. The possible reason for the lack of effect of FB and DDBE on the positive mood of participants may be related to the increase in the social stress of participants during the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the society [73]. In conclusion, this study found that FB and DDBE had psychological benefits for both pre-hypertensive and hypertensive middle-aged adults. As the relaxing effect of DDBE on reducing negative moods was first observed after the four-week DDBE intervention, further studies are suggested to explore more potential beneficial effects of these two relaxation approaches on mental health in Hong Kong.

Sustained effects and potential beneficial effects of FB and DDBE

FB has been reported to have potential psychological and

physiological health benefits. Only two studies have examined the

sustained effects on the physical response or on both the emotional

and physical responses to FB [36,37]. Although a previous study

did not observe a sustained effect of FB on lowering BP, there

was a reduction in the anxiety and quality of life measure at eight

weeks after a three-day forest therapy program [36]. In the present

study, the results of the sustained effect on both physiological

and psychological indicators at the eight-week follow-up was not

completely consistent with those of the previous study. The results

of this study found that the differences of SBP and DBP were not

statistically at the eight-week follow-up. There was a significant

sustained effect on lowering PR only. However, a significant

sustained reduction in the anxiety level and negative mood state of

participants in the FB group was not observed in this study. These

results were not consistent with the potential mental health benefit

of FB reported in a previous study. A previous study reported that

20-minute slow abdominal breathing could maintain a lowering

effect on BP at three months after a five-week intervention [74]. In

this study, the sustained lowering effect of DDBE was not observed

on BP and PR, and the result was not consistent with that of the

previous study.

Given that few studies investigated the sustained effect of FB,

researchers should further explore the potential sustained effect of

FB and DDBE on cardiac and mental health in future studies to set

up the most appropriate frequency and duration of FB and DDBE

interventions as clinical guidelines for healthcare professionals in

the prevention of pre-hypertension or hypertension. To explore the

potential beneficial effects of FB, a set of questions was established

to collect participants’ subjective data on practicing relaxation

techniques at eight weeks after the interventions. The results

indicated that almost all participants practiced FB after completing

the program. The reasons included feeling relaxed while connecting

to the natural environment, good-quality sleep, restoring attention

to therapy, and positive mood.

Limitations of the study

The participants of this study were recruited from the webpage of two social associations in Hong Kong. The sample population of this study was limited to the generalizability of the results to the whole population due to the possibility of underpowering the study or type I or type II errors of the study. Because of the convenience of sampling, the current study was limited to eligible members from the two social associations. They are not representative of the entire pre-hypertensive and hypertensive populations. Moreover, since researchers were not blinded to group allocation, this may have led to bias. Further studies should be conducted in a larger and representative sample, blinded to group assessment, to lower the risk of bias. Finally, with a view to combating the COVID-19 epidemic, participant recruitment was affected by the regulation of prohibition on group gatherings for outside activities. Since March 2020, due to the COVID pandemic, all social gathering activities were prohibited, particularly the indoor activities in Hong Kong. Information session could not be held for the target population. As a result, only small numbers of participants can be recruited, and the imbalanced number of participants in each group. The results may be considered to have insufficient power to extrapolate the statistical analysis results to the overall pre-hypertensive and hypertensive middle-aged population.

Summary of discussion

The major findings of this study were that FB was associated with a reduction in SBP, anxiety level, and negative mood states in the FB group after completion of four sessions of FB on four consecutive weekends. FB had no effect on lowering DBP and PR as well as increasing the positive mood of the participants. However, DDBE was associated only with a reduction in PR, anxiety level, and negative mood of tension-anxiety, fatigue, and confusion among the participants after four sessions of DDBE for four consecutive weekends with 10 minutes of self-practice of DDBE twice a day at home. At the eight-week post-intervention follow-up, the sustained effect of FB was observed on lowering PR only. Contrarily, the score of state anxiety level of the FB group was found to be increased at the follow-up assessment. There was no sustained effect of DDBE on both physiological and psychological outcomes.

Implications for practice

Prolonged stress has been reported to be positively associated

with hypertension and cardiovascular disease. In recent decades,

FB has been proposed in Japan and the US as a preventive strategy

for lowering BP and relieving stress and negative moods among

pre-hypertensive or hypertensive adults [75]. In contrast, DDBE

has been reviewed as an alternative relaxation approach to

lowering BP by the American Heart Association [76]. The shortterm

psychological beneficial effects of DDBE were observed

in pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults who were taking

antihypertensive medication [72].

FB and DDBE provide a practical option and an alternative

approach for individuals with pre-hypertension and adults with

hypertension on BP control. As FB and DDBE have been proven

to have little to no side effects, healthcare providers may promote

these approaches as part of the initial treatment for the prevention

of hypertension. The findings in this study have demonstrated that

FB and DDBE may reduce psychological stress in pre-hypertensive

and hypertensive middle-aged adults, which further alters the

BP and PR of these individuals. This study provides preliminary

evidence to establish clinical guidelines for FB and DDBE as health

promotion strategies. Healthcare professionals should consider the

practice of FB and DDBE as preventive measures to reduce stress

and lower BP in patients with pre-hypertension and hypertension.

Recommendations for future research

Considering the short-term cardiovascular health beneficial effects of FB as observed in this study, it is suggested that the researchers conduct additional clinical studies to explore the longterm health benefits of FB in pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults. FB may be compared with other relaxation approaches to provide stronger evidence of their clinical effects. The most effective duration and frequency of FB should be explored and examined in further studies to provide an appropriate protocol for health professionals to establish evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of hypertension. Measurements should be included in the post-intervention follow-up assessment to continually explore the sustained physiological and psychological effects of FB if used as a recreational activity. The beneficial effect of FB on improving social interaction and family relationships can be explored in future studies to identify these advantages. At last, the change of calories consumption, sodium intake of participants should be monitored and compared between interventions to immunize the possible covariate effects in the further studies.

Conclusions

Two hours of FB with four sessions on four consecutive

weekends has been observed to have physiological and psychological

relaxing effects on middle-aged adults with elevated BP. FB is a

simple, affordable, and enjoyable complementary intervention

to reduce anxiety, improve mood, and lower BP. This study is the

first to examine and compare the effectiveness of FB and DDBE in adults with pre-hypertension or hypertension in Hong Kong. These

results may provide indications to healthcare professionals and

populations at risk for integrating FB into the management of high

blood pressure and/or DDBE in the management of mental health.

It is also concluded that this feasibility study has confirmed the

appropriateness of the intervention plan, the acceptable process in

subject recruitment, and the efficacy of the outcome measurements,

which established the study protocol and foundation for future

randomized control trials on the topic.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the founder of Shirin Yoku Hong Kong, Ms. Amanda Yik, and her team of the Nature and Forest Therapy Guides with the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs for their advice and guidance in the forest therapy intervention. I appreciated Ms. Emma Sun, a qualified counselor, for her supervision in DDBE intervention. We express our gratitude to Ms. Erica Ching for her contribution in poster design. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Katherine Ka-Yin YAU and Alice Yuen LOKE; Data curation, Katherine Ka-Yin YAU; Investigation, Katherine Ka- Yin YAU; Methodology, Katherine Ka-Yin YAU and Alice Yuen LOKE; Project administration, Katherine Ka-Yin YAU; Supervision, Alice Yuen LOKE; Writing – original draft, Katherine Ka-Yin YAU; Writing – review & editing, Alice Yuen LOKE; Visualization: Katherine Ka- Yin YAU.

Conflicting interests

The Abstract of this title was presented in the 32nd International Nursing Research Congress by Sigma, 22-26 July 2021, Singapore. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

The Human Subjects Ethics Sub-committee (HSESC Reference Number: HSEARS2020123006) and the Clinical Research Ethics Sub-committee (CSRES reference Number: CRESC202002) of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University approved this study. All participants gave informed consent.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author biography

Author biography: Katherine KY Yau currently work as Senior Lecturer at Tung Wah College. Katherine does research in Health and Nursing science. Her research interests are in forest therapy, other complementary and alternative approaches such as deep breathing and nursing education.

References

- O'Brien E (2017) The Lancet Commission on hypertension: Addressing the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations. J Clin Hypertens 19(6):564-568.

- Li J, Zheng H, Du H, Tian X, Jiang Y, et al. (2014) The multiple lifestyle modification for patients with prehypertension and hypertension patients: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 4(8): e004920.

- Zhang W, Li N, Prevalence, (2011) risk factors, and management of prehypertension. Int J Hypertens, 2011: 605359.

- World Health Organization. Hypertension. What is hypertension. (Accessed 24 January 2020).

- Sierra C, de la Sierra A (2008) Early detection and management of the high-risk patient with elevated blood pressure. Vasc Health Risk Manag 4(2): 289-296.

- Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang Z, Chen Z, (2018) Status of Hypertension in China: Results from the China Hypertension Survey, 2012-2015. Circulation 137(22): 2344-2356.

- Zhang Y, Moran AE (2017) Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among young adults in the United States, 1999 to 2014. Hypertension 70(4): 736-742.

- Booth 3rd John N, Li J, Zhang L, Chen L, Muntner P, et al. (2017) Trends in prehypertension and hypertension risk factors in US adults: 1999–2012. Hypertension 70(2): 272-284.

- Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Gupta R, et al. (2013) Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 310(9): 959-968.

- Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, et al. (2003) Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA 289(16): 2083-2093.

- Sohl SJ, Wallston KA, Watkins K, Birdee GS (2016) Yoga for risk reduction of metabolic syndrome: patient-reported outcomes from a randomized controlled pilot study. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med 2016: 3094589.

- McDermott K, Kumar D, Goldman V, Feng H, Mehling W, et al. (2015) Training in ChiRunning to reduce blood pressure: a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med 15: 368.

- Kunikullaya KU, Goturu J, Muradi V, Hukkeri PA, Kunnavil R, et al. (2015) Music versus lifestyle on the autonomic nervous system of prehypertensives and hypertensives-a randomized control trial. Complement Ther Med 23(5): 733-740.

- Kunikullaya KU, Goturu J, Muradi V, Hukkeri PA, Kunnavil R, et al. (2016) Combination of music with lifestyle modification versus lifestyle modification alone on blood pressure reduction – A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 23: 102-109.

- Spruill TM (2010) Chronic psychosocial stress and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 12(1): 10-16.

- American Heart Association. Healthy lifestyle. Stress Management.

- Li Q, Morimoto K, Nakadai A, Inagaki H, Katsumata M, et al. (2007) Forest bathing enhances human natural killer activity and expression of anticancer proteins. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 20 (2): 3-8.

- Li Q, Kobayashi M, Kumeda S, Ochiai T, Miura T, et al. (2016) Effects of forest bathing on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters in middle-aged males. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2587381-2587387.

- Li Q, Morimoto K, Kobayashi M, Inagaki H, Katsumata M, et al. (2008) Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of anit-cancer proteins. Int J Immumopathol Pharmacol 21(1): 117-127.

- Li Q, Morimoto K, Kobayashi M, Inagaki H, Katsumata M, et al. (2008) A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins in female subjects. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 22(1): 45-55.

- Li Q (2010) Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ Health Prev Med 15: 9-17.

- Li Q, Kobayashi M, Wakayama Y, Inagaki H, Katsumata M, et al. (2009) Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 22(4): 951-9.

- Takayama N, Korpela K, Lee J, Morikawa T, Tsunetsugu Y, et al. (2014) Emotional, restorative and vitalizing effects of forest and urban environments at four sites in Japan. Int J Environ. Res Public Health 11 (7): 7207-7230.

- Stevenson MP, Schilhab T, Bentsen P (2018) Attention Restoration Theory II: a systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 21(4): 227-268.

- Yu CP, Hsieh H (2020) "Beyond Restorative Benefits: Evaluating the Effect of Forest Therapy on Creativity. Urban For Urban Green 51:126670.

- Li Q, Otsuka T, Kobayashi M, Inagaki H, Katsumata M, et al. (2011) Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. Eur J Appl physiol 111(11): 2845-2853.

- Mao GX, Cao YB, Lan XG, He ZH, Chen ZM, et al (2012) Therapeutic effect of forest bathing on human hypertension in the elderly. J Cardiol 60: 495-502.

- Lanki T, Siponen T, Ojala A, Korpela K, Pennanen A et al. (2017) Acute effects of visits to urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in women: a field experiment. Environ Res 159: 176-85.

- Song C, Ikei H, Kobayashi M, Miura T, Taue M, (2015) Effect of forest walking on autonomic nervous system activity in middle-aged hypertensive individuals: A pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12: 2687-2699.

- Song C, Ikei H, Kobayashi M, Miura T, Li Q, et al. (2017) Effects of viewing forest landscape on middle-aged hypertensive men. Urban For Urban Green 21: 247-252.

- Yu CP, Lin CM, Tsai MJ, Tsai YC, Chen CY et al. (2017) Effects of short forest bathing program on autonomic nervous system activity and mood states in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14: 897.

- Zhou Z, Dongping M, Feng L, Changyu C, Chi L et al. (2017) Influence of forest bathing on blood pressure, blood lipid and cardiac function of hypertension sufferers. Chin J Convalescent Med 26(5).

- Feng L, Zhou Z, Tingyan C (2017) Influence of forest bath on vascular function and the relevant factors in military patients with hypertension. Chin J Convalescent Med 26(4).

- Horiuchi M, Endo J, Akatsuka S, Hasegawa T, Yamamoto E, et al. (2015) An effective strategy to reduce blood pressure after forest walking in middle-aged and aged people. J Phys Ther Sci 27: 3711-3716.

- Lee JY, Lee DC (2014) Cardiac and pulmonary benefits of forest walking versus city walking in elderly women: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Eur J Integr Med 6: 5-11.

- Sung J, Woo JM, Kim W, Lim SK, Chung EJ et al. (2012) The effect of cognitive behavior therapy-based “forest therapy” program on blood pressure, salivary cortisol level, and quality of life in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens 34: 1-7.

- Song C, Ikei H, Miyazaki Y (2017) Sustained effects of a forest therapy program on the blood pressure of office workers. Urban For Urban Greening 27: 246-252.

- Ochiai H, Ikei H, Song C, Kobayashi M, Takamatsu A, et al. (2015) Physiological and psychological effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males with high-normal blood pressure. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12: 2532-2542.

- Ochiai H, Ikei H, Song C, Kobayashi M, Miura T, et al. (2015) Physiological and psychological effects of a forest therapy program on middle-aged females. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12: 15222-15232.

- Hansen M, Jones R, Tocchini K, (2017) Shinrin-Yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy: a state-of-the-art review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(8): 851.

- Yau, KK, Loke AY (2020) Effects of forest bathing on pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults: A review of the literature. Environ Health Prev Med 25: 1-17.

- Ma X, Yue Z, Gong Z, Zhang H, Duan N, et al. (2017) The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front Psychol 8: 874.

- Kow F, Adlina B, Sivasangari S, Punithavathi N, Ng K, et al. (2018) The impact of music guided deep breathing exercise on blood pressure control - A participant blinded randomised controlled study. Med J Malays 73(4): 233-238.

- Joseph CN, Porta C, Casucci G, Casiraghi N, Maffeis M, et al. (2005) Slow breathing improves arterial baroreflex sensitivity and decreases blood pressure in essential hypertension. Hypertension 46: 714-718.

- Vasuki G, Sweety LM (2017) The study of usefulness of deep breathing exercise (non-pharmacological adjunct) on blood pressure in hypertensive patients. J Dent Med Sci16: 59-62.

- Grossman E, Grossman A, Schein MH, Zimlichman R, Gavish B, et al. (2001) Breathing control lowers blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens 15: 263.

- Elliott WJ, Izzo JL, White WB, Rosing DR, Snyder CS, et al (2004) Graded blood pressure reduction in hypertensive outpatients associated with use of a device to assist with slow breathing. J Clin Hypertens 6: 553-559.

- Sundaram B, Maniyar PJ, Singh VP (2012) Slow breathing training on cardio-respiratory control and exercise capacity in persons with essential hypertension--a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther 6: 17-21.

- Vasuki G, Sweety LM (2017) The study of usefulness of deep breathing exercise on blood pressure in pre-hypertensive and hypertensive patients. Indian J Clin Anat Physiol 4: 400-403.

- Yau KKY, Loke AY (2021) Effects of diaphragmatic deep breathing exercises on prehypertensive or hypertensive adults: A literature review. Complementary therap in Clin practice 43(2021): 101315.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, et al. (2018) Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. 1979) 71(6): 1269-1324.

- Centre for Health Protection of Department of Health. The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Hypertension – the preventable and Treatable Silent Killer.

- New Life psychiatric Rehabilitation Association. Core services. Community support services.Project/services.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner AG (2007) *Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2): 175-191.

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJL Erlbaum Associates.

- The Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation department (AFCD). Country & Marine Parks. Visiting country and Marine Parks. Country Parks. Tai Po Kau Special Area, Tai Po Kau Nature Reserve.

- Kwok HK (2017) Flocking behavior of forest birds in Hong Kong, South China J For Res 28: 1097-1101.

- Association of Nature & Forest Therapy Guides & Programs. What is Forest Therapy. The Practice of forest therapy.

- Hazel A, Les R (2015) Liminality. International Encyclopedia of the social & Behavioral Sciences (Second edition) 131-137.

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman L (1992) Profile of Mood States (POMS) manual. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

- American Psychological Association. Psychology Topics-Anxiety.

- Chen KM, Snyder M, Krichbaum K (2002) Translation and equivalence: The profile of mood states Short Form in English and Chinese. Int J Nurs Stud 39: 619-624.

- Jette AM, Harris BA, Sleeper L, Lachman ME, Heislein D, et al. (1996) Home-based exercise program for nondisabled older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 44(6): 644-649.

- Chen KM (2000) The Effects of Tai Chi on the Well-being of Community-dwelling Elders in Taiwan, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (Accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jcobs GA et al. (1983) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA.

- Julian LJ (2011) Measures of anxiety: State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‐Anxiety (HADS‐A). Arthritis Care Res 63: S467-S472.

- Chua B, Mutang J, Ismail R (2018) Psychometric properties of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) among Malaysian University Students. Sustainability 10(9): 3311.

- Shek DT (1993) The Chinese version of the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory: Its relationship to different measures of psychological well‐being. J Clin Psychol 49(3): 349-358.

- Hui N (2003) An evaluation of two behavioral rehabilitation programs in improving the quality of life in myocardial infarct patients in Hong Kong. (Master’s thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University), (Accessed 24 September 2019).

- Li XM, Xiao WH, Yang P, Zhao HX (2017) Psychological distress and cancer pain: Results from a controlled cross-sectional survey in China. Sci Rep 7: 39397.

- Harneet K, Saravanan S (2014) Effect of slow breathing on blood pressure, heart rate and body weight in prehypertensive subjects of varying body mass index. Int J Sci Res 3(6): 863-867.

- D'silva F, Vinay H, Muninarayanappa NV (2014) Effectiveness of deep breathing exercise (DBE) on the heart rate variability, BP, anxiety & depression of patients with coronary artery disease. J Health Allied Sci 4(1): 035-041.

- Choi E, Pui H, Hui B, Pui H, Wan EYF, et al. (2020) Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health17(10): 3740.

- Lin G, Xiang Q, Fu X, Wang S, Wang S, et al. (2012) Heart rate variability biofeedback decreases blood pressure in prehypertensive subjects by improving autonomic function and baroreflex. J Altern Complement Med 18: 143-152.

- Yau KK, Loke AY (2020) Effects of forest bathing on pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults: A review of the literature. Environ Health Prev Med 25(1): 23.

- Mahtani KR, Nunan D, Heneghan CJ (2012) Device-guided breathing exercises in the control of human blood pressure: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 30: 852-860.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...