Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Research ArticleOpen Access

Calligraphic Handwriting (CCH) Effects on Moods and Anxiety of Type II Diabetes Patients Volume 3 - Issue 2

Henry S.R. Kao1*, C.H. Goan1 Xintian Li2, Jinghan Wei2, Nianfeng Guo2, Jiatang Zhang2

1Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

Received:June 19, 2021 Published: July 01, 2021

*Corresponding author: Henry S.R. Kao, Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2021.03.000157

Abstract

Background

Chinese Calligraphic Handwriting (CCH), a WHO (2019) recognized effective treatment, enhances our cognitive abilities, relaxed bodily conditions and stabilized emotions. It has successfully treated the emotion-related anxieties and the moods that are associated with several diseases and disorders. The present study tested this intervention on Diabetes patients.

Method

16 type II diabetes patients and 16 healthy subjects participated. Each group performed both the CCH tasks of brush handwriting of Chinese characters and the brush drawing of geometric patterns. The Chinese versions of STAI and POMS measured the effects of brush writing and brush drawing tasks. on the participants. Both scales were administered to all participants before and after a 40-minute training session.

Findings

The patients group significantly improved on Pre-Post measures of the STAI in both the brush writing (F= 11.97; p=0.004) and brush drawing (F=14.08, p=0.002) tasks. However, the healthy subjects group also showed similarly a pre-post significant effects on the STAI scores from the brush writing (F = 32.02; p = 0.000) and the drawing tasks (F= 14.05, p=0.002).

Moreover, both groups showed a significant reduction in the postforms states of Tension-Anxiety, Depressed-Dejection and Confusion-Bewilderment in the brush writing task (P<0.001), but only Tension-Anxiety and Depressed-Dejection in the brush drawing tasks (P<0,001), The reduction in each case from the patient groups is greater than that from the healthy subject’s group (0.001).

Interpretation

The Brush Writing and Brush Drawing as treatments have shown significant improvements in STAI and some POMS states of the practicing Type II diabetes patients.

Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese handwriting, especially with a brush, can be conceptualized as an act involving the whole body of the writer in which cognitive planning, organizing, and processing of visualspatial patterns of the character take place. Motor control and maneuvering of the brush following the character configurations involve the whole body projected relative to the geometry of each character. The activity of brush writing is essentially an external projection and execution of the writer’s internal cognitive images of the character. There is therefore an integration of mind, body, and character interwoven in the dynamic calligraphic process. The heritage of Chinese calligraphy is traditionally used to enhance an individual’s self-reflection and cultivation.

Our research in the past 30 years has identified five dimensions of beneficial behavior arising from the practice of Chinese calligraphy handwriting (CCH). These are visual attention, cognitive activation, physiological slowdown, emotional relaxation and behavioral change and development Kao [1]. These findings have contributed significantly to the improvement of the practitioner’s psychological health and wellbeing.

Chinese characters have different visual geometric properties. Some characters are extremely detailed and require several strokes (Fly, dragon) while some other characters are symmetrical (South, grass) some are parallel (Wang, book. Of course, there are also characters that are neither asymmetrical nor parallel (Heart, Yao).

Directional characters possess character forms of shapes that orient upwards, downwards, to the right or to the left (Mountain, dry). Some characters have strokes that are closely linked together as a unit (Foot, Shen); characters without such features are nonconnected characters (Small, swimming). Closed characters have enclosed or holes in the construction (Crystal, vessel) and the nonclosed characters do not have these features (Than, coincidence). We have found that these visual-spatial variations of the characters have a powerful impact on the practitioner’s writer’s bodily and psycho-emotional states during dynamic calligraphic execution.

Effects of Calligraphy Training

Cognitive Effects

The practice of Chinese calligraphic training has been confirmed to facilitate and increase some cognitive changes. Cognitive changes associated with CCH practice include such intellectual abilities as Spatial Ability, Abstract Reasoning, Short-term Memory, Picture Memory, and cognitive Reaction Time Kao [2] as well as cognitive and perceptual tasks such as visual and auditory attention, concentration, and spatial reasoning Kao [3].

Physiological and Cognitive Neural Effects

Some of the psychological effects studied over the years have included reduced heart rate, blood pressure, skin conductance, raised skin temperature, slower respiration, and relaxed muscular tension. This calligraphic impact has also been confirmed for attention and emotional stability and mental relaxation Kao et.al. [4]. In addition, recent brain-imaging studies have further confirmed the CCH training and practice effects on shaping the structure and functions of the brain Xu et.al. [5]; Chen et al. [6] and better executive functions and stronger resting-state functional connectivity in related brain regions Chen et al. [7]. These findings provide powerful confirmation of CCH’s impact on the brain’s cognitive neural dimensions of the practicing calligraphers.

Bio-emotional Effects

The direct outcome of such changes as well as the overall physical quiescence evokes sensory feedback: states of emotional relaxation, calmness, tranquility, and peace of the mind, which offers a psychological incentive for further motor control and execution of the brushing acts. In other words, the reason for continuing is due to the physiological slowdown as well as the soothing and relaxing states of emotions Kao, 2006; Kao [8]; (Kao, Zhu, Chao, Chen, Lie & Zhang, 2014). Our recent study on CCH training effects on HRV coherence increase is another evidence of its effectiveness Lam et.al. [9].

Foundations of CCH Treatment on Emotional States of Diabetes

We know that diabetes can cause a wide array of complications, which would exert great influence on diabetic patients’ emotions and increased stress. Anxiety and depression are common occurrences among these patients and often debilitate them Karlsen et.al.[10] It is found that in a meta-analysis that the prevalence of depression among people with diabetes was about twice as high as that among those without diabetes Anderson et.al.[11] Therefore, in the treatment of diabetes, it is not enough to consider physical factors alone. Healthy nutrition and regular exercise are important, but we must also pay attention to the emotional factors that are closely related to the quality of life of diabetic patients. Evidencebased behavioral interventions are pressing and needed.

Researchers have advocated over the years a behavioural approach, which involves biofeedback and relaxation training in the treatment of diabetes Fiero et.al. [12]; Mcginnis et.al. [13]. In addition, they have also found the CCH practice can relax the emotions and mood states of schizophrenic patients Fan et.al. [14] and the autistic children Kao et.al. [15]. In recent years, our CCH interventions have further been applied to treat patients with emotion-related diseases, conditions, or disorders. These have included patients with anxiety disorders (Dong, e; al, 1996); Chinese Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma patients experiencing mood state disturbances (Yang, Li, Hong & Kao, 2009), childhood survivors of the 2008 Sichuan-China earthquake with moods disturbance and distress symptoms -- helping reduce PTSD symptoms, cortisol levels and stress, (Zhu, Wang, Kao, Zong, et., al. 2014) as well as breast cancer patients with anxiety and comorbid depression Liu et.al. [16]; Wagner [17].

On the strength of the foregoing clinical studies, the present investigation aimed to test and demonstrate the effectiveness of the CCH training in helping patients with Type II diabetes to reduce their stress, anxiety and mood states.

Method

Measures

Sixteen participants diagnosed with type II diabetes and sixteen healthy control subjects received the CCH treatment, the brush writing of Chinese characters or drawing treatment, which involved drawing of geometric figures with a brush. The Chinese version (STAI; Form Y-1, translated by Ye, 1988) of the State and Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI) Form Y-2, STAI: Speilberger et.al. [18] was employed to measure the anxiety level of the participants. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) Lorr et.al. [19,20] was adopted to evaluate subjective emotional experiences of the normal subjects as well as the clinical patients in six mood states: Depression- Dejection (D), Tension-Anxiety (T), Anger-Hostility (A), Vigour (F), and Confusion-Bewilderment (C).

Design

The 16 normal adults and 16 diabetic patients were randomly assigned to either the CCH practice group or the figure-drawing group with 16 participants in each group. They each performed the respective brush task, writing or drawing, for 45 minutes. The instruments used included a brush made of lamb hair and the rice paper. The writing materials were Chinese characters in a style containing mainly linear strokes and topological properties, while that for drawing consisted of meaningless geometric patterns. The STAI and the POMS were administered to all participants before and after the brush task for the patients as well as the healthy controls.

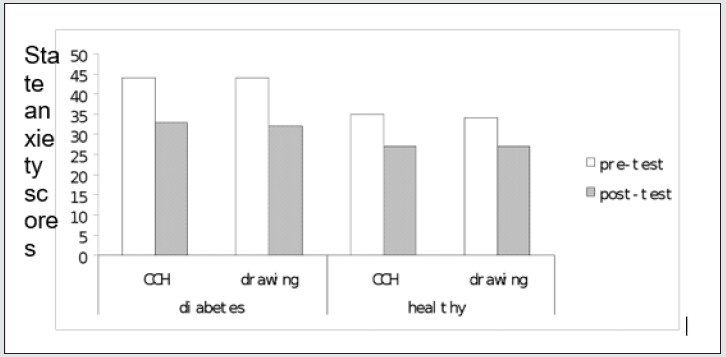

Results

Based on the State-Anxiety Inventory (S-AI), patients significantly improved on measures of state anxiety (SA) in both the brush writing task (F= 11.97; p=0.004) and the brush drawing task (F=14.08, p=0.002) treatment conditions. In addition, the healthy controls also showed an improved positive effect on SA in both the brush writing (F = 32.02 (p = 0.000) and the brush drawing tasks (F= 14.05, p=0.002). Overall, the patient group’s SAI magnitude reduction is shown greater than that of the healthy controls when the brush writing and the brush drawing tasks are pooled together. (F=5.84, p<0.05?). In addition, The SAI magnitude reduction from the drawing tasks is found to be greater than that of the brush writing task is interesting (F = 5.33; p <0.05?). (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mean changes in state anxiety scores in practising calligraphy or drawing for diabetes and healthy subjects.

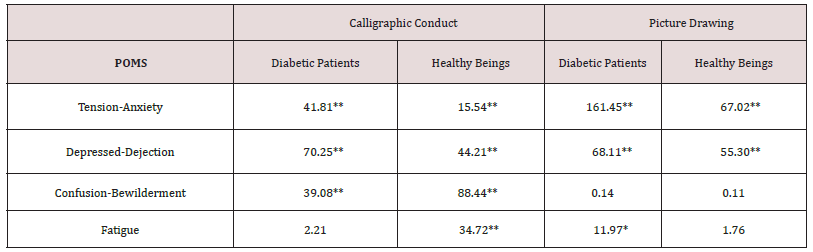

On the other hand, using the POMS, all participants, including both the patients and the healthy adults, showed a significant reduction in the mood states of tension-anxiety, depresseddejection and confusion-bewilderment after the CCH practice, while a reliable decrease in the states of tension-anxiety, depresseddejection was observed after drawing in both groups. Furthermore, healthy adults, but not the patients, improved in fatigue after the CCH practice, while the patients, but not the healthy adults, improved in fatigue after the brush drawing session (Table 1).

Note * P<0.05 **P<0.001

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate the effects of the calligraphy handwriting and drawing on emotional modulation of patients with Type II diabetes and the normal adults. Results have firstly confirmed the stabilizing functions of both tasks, resulting in a relaxation of anxiety. Secondly, improvement in several states of the moods has been found to relate to both types of brushing tasks: Tension-Anxiety, Depression-Dejection, and Confusion- Bewilderment after the CCH practice and Tension-Anxiety and Depression-Dejection after the drawing practice. The contribution of brush writing and brush drawing to the emotional regulation of the diabetes Type II patients is supported in this study. Finally, the findings help to validate the viability of both the calligraphy practice and brush drawing as a new technique as well as an alternative model of behavioural treatment, with special reference to the intervention of emotional and psychosomatic symptoms of diabetes.

These preliminary results are overwhelming and are in line with those similar findings obtained in our other clinical studies on the CCH effects on the moods, anxiety, symptom distress and other emotions that are previously reported.

We have established that Chinese brush handwriting has measurable behavioral, psychological, and emotional effects. We also know that CCH practitioners have enhanced brain functioning, improved cognitive abilities and intellectual skills, and better emotional states. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized and endorsed our earlier clinical investigations as having contributed to a major body of theory, knowledge, and a system of treatment Fancourt et.al. [21]. CCH is an effective method for health and therapeutic interventions on cognitive activation, affective-emotion-related anxieties, moods, and distress and as a tool that contributes to the practitioner’s wellbeing and general health. We are pleased that the present research on Type II diabetes has added clinical validation of the CCH intervention for the benefit of human health, wellbeing, and disease treatment.

Funding

Not applicable

References

- Kao HSR (2010) Calligraphy therapy: A complementary approach to psychotherapy, Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 1(1): 55-66.

- Xu M, Kao HS, Zhang M, Lam SP, Wang W et.al. (2013) Cognitive-Neural Effects of Brush Writing of Chinese Characters: Cortical Excitation of Theta Rhythm. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013(3): 975190-975190.

- Kao HSR (1992a) A review of research on Chinese brush Calligraphy writing. International Journal of Psychology, 27 (3, 4): pp. 137.

- Kao HSR (1992b) Effect of calligraphy writing on cognitive processing. International Journal of Psychology, 27 (3,4): pp. 138.

- Mcginnis RA, Mcgrady A, Cox SA, Grower-dowling KA (2005) Biofeedback-Assisted Relaxation in Type 2 Diabetes, Diabetes Care, 28(9): 2145-2149.

- Lorr M, McNair DM (1982) Profile of Mood States, Bi-Polar Form. California: Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

- Karlsen B, Bru E, Hanestad BR (2002) Self-reported psychological wellbeing and disease-related strains among adults with diabetes, Psychology and Health 17(4): 459-473.

- Dong XP, Jia Ji Ming, Wang Jun, Cuei ZL, Zhang RX et.al. (2006) A control study of calligraphy training plus Venlafaxine in the treatment of anxiety disorder. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science, 15(5): 445-446.

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) The prevalence of comborbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis, Diabetes Care 24(6): 1069-1078.

- Yang XL, Li HH, Hong HH, Kao HSR (2010) The effects of Chinese calligraphy handwriting and relaxation training in Chinese Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma patients. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 47 (5): 550-559.

- Kao HSR, Lam PW, Robinson L, Yen NS (1989) Psychophysiological Changes Associated with Chinese Calligraphy. In P Plamondon, CU Suen, ML Simner (Eds.), Computer recognition and human production of handwriting. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. 349-381.

- Chen W, Chen C, Yang P, Bi S, Liu J et.al (2019). Long- term Chinese calligraphic handwriting reshapes the posterior cingulate cortex: A VBM study. PLOS ONE, 14(4): e0214917.

- Speilberger CD (1983) Manual for the State- Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.

- Chen W, He Y, Gao Y, Zhang C, Chen C et.al (2017) Long-Term Experience of Chinese Calligraphic Handwriting Is Associated with Better Executive Functions and Stronger Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Related Brain Regions. PLOS ONE, 12(1): e0170660.

- Kao HSR (2007) Chinese calligraphic handwriting (CCH): a science for health and behavioral therapy. International Journal of Psychology, 41(4): 282-286.

- Liu, Anna, (2017) "The Effects of Chinese Calligraphy on Reducing Anxiety and Comorbid Depression Levels Among Breast Cancer Patients in Hong Kong". Dissertations, 1636.

- Kao HSR, Lai MF Fok, WY Gao, DG Math (2000) Effects of calligraphic treatment of negative behaviours of autistic children in the school and at home. Paper for the Autism-Europe Congress, May 19-21: 2000, Glasgow.

- Wagner S (2018) Calligraphy Therapy Interventions for Managing Depression in Cancer Patients: A Scoping Study. Altern Integra Med 7: 260.

- Fan ZS, Kao HSR, Wang YL, Guo NF (1999) Calligraphic Treatment of Schizophrenic Patients. In G. Leedham, M Leung, V Sagar, X-H Xiao. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 9th Biennial Conference of the International Graphonomics Society. June 28-30. Nanyang Technological University. pp.125-131.

- Lam SP W, Kao HSR, Kao X, Fung MMY, Kao TT et.al. (2019). HRV regulation by calligraphic finger writing and Guqin music: A pilot case study. NeuroRegulation, 6(1): 42-51.

- Fancourt D, Finn S (2019) What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Health Evidence Network synthesis report 67. WHO-Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...