Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1217

Research ArticleOpen Access

A Pilot Study into the Effectiveness of an Internet and Video Consultation Multidisciplinary Programme for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Fibromyalgia Volume 4 - Issue 3

Natasha Watkinson1 and Miranda D Harris1,2*

1The School of Allied Health and Community, University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, United Kingdom

2Nutritional Therapy, The School of Allied Health and Community, University of Worcester, United Kingdom

Received: March 11, 2022 Published: August 03, 2022

*Corresponding author: Miranda Harris, Senior Lecturer, Nutritional Therapy, The School of Allied Health and Community, University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, WR2 6AJ, United Kingdom.

DOI: 10.32474/OAJCAM.2023.04.000179

Abstract

Introduction: There are currently no disease modifying treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) or fibromyalgia, and multidisciplinary therapy (MDT) is of interest. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a three-month Internet MDT in the patients’ homes on dietary and lifestyle behaviors, disease impact and symptoms.

Methods: This was a pilot study conducted between November 2020 and March 2021, and 26 participants were recruited via advertising on UK social media. 18 participants completed the study in non-individualized Internet programme (N=12) and individualized Internet programme and video consultation (N = 6) intervention groups. The Internet programme included modules on nutrition, endocrinology, mental health, lifestyle, relationships and exercise and the individualized group received video consultations with Nutritional Therapists or Peer Counsellors in addition. Outcome measures included the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR), Hospital Anxiety and Depression – Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A), the short Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and a lifestyle questionnaire.

Results: After three months there were statistically significant improvements in dietary quality (p-value <0.0005), FIQR (p-value <0.014), symptom subscale (p-value < 0.006) and HADS-A (p-value < 0.041). The individualized group saw greater improvements in dietary quality (p-value > 0.04) and HADS-A (p value> 0.01) than the non-individualized group.

Conclusions: This pilot study shows improvements in dietary quality, disease impact, symptoms and anxiety in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia might be found through an Internet based MDT; however possible bias exists and randomized controlled trials with a larger sample are required.

Keywords: Chronic fatigue syndrome; Fibromyalgia; Multidisciplinary; Online Intervention; nutrition; effectiveness

AbbreviationsCBT:Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; CERP: The Chrysalis Effect Recovery Programme; CFS/ME: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis; FIQR: Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FODMAP: Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols; FFQ: Food Frequency Questionnaire; HADS-A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression – Anxiety Subscale; HPA: Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal; IBS: Irritable bowel Syndrome; MCID: Minimum Clinically Important Difference; MDT: Multidisciplinary Therapy

Research Article

Background

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (CFS/ ME) and fibromyalgia are chronic conditions predominantly affecting women, with no medically explained aetiology. They share many of the same symptoms (Abbi and Natelson, [1]) including chronic fatigue and pain, sleep disturbances and cognitive issues (Jones et al. [2]; Castro-Marrero, Sáez-Francàs, et al. [3]). There is a high degree of comorbidity, as cohort studies have estimated between 41-57% of CFS/ME patients also have fibromyalgia (Dansie et al. [4]; Castro-Marrero, Faro, et al. [5]), whilst 75% of fibromyalgia patients also reported fatigue (Collin et al. [6]). In addition anxiety and depression are found in 57% of CFS/ME patients (Dansie et al. [4]) and 30-60% of fibromyalgia patients (Schmidt-Wilcke and Clauw, [7]), and mental health problems may exacerbate symptoms, though the cause-and-effect relationship was not understood (Lempp et al. [8]).

CFS/ME is not diagnosed until alternative diagnosis have been excluded (NICE, [9]), whilst fibromyalgia is diagnosed by selfreporting symptoms (Jones et al. [2]), thus the UK prevalence of CFS/ME (0.2-0.4%) (NICE, [9]; Collin et al. [6]) is thought to be around ten times lower than the prevalence of fibromyalgia (5.4%) (Jones et al. [2]). It is argued by Avellaneda-Fernández et al. [10] that some CFS/ME patients were diagnosed with fibromyalgia because fatigue was not the main symptom, and a possible single syndrome hypothesis suggested these conditions share similar pathophysiology (Abbi and Natelson [1]).

Pathophysiology

There are several hypotheses about the aetiology of CFS/ ME including depression (Clements et al. [11]), viral infection (Puri [12]) and mitochondrial dysfunction (Myhill, Booth and McLaren-Howard, [13]); similarly fibromyalgia may be triggered by psychological stress and viral infections (Schmidt-Wilcke and Clauw, [7]). A large body of evidence highlights disruptions in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and neuroendocrinological pathways as a possible pathogenic mechanism in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia (Avellaneda-Fernández et al. [10]; Becker and Schweinhardt, [14]; Glassford [15]). Several disorders in the production of the glucocorticoid hormones serotonin and dopamine were identified in CFS/ME (Avellaneda-Fernández et al. [10], Glassford [15]) and evidence has been found for reduced levels of serotonin, dopamine and noradrenalin in patients with fibromyalgia (Light et al. [58]), along with increases in opioids, glutamate and substance P (Russell et al. [17]). It was hypothesized neurotransmitter dysfunctions contributed to central sensitization of the nervous system (Avellaneda Fernández et al. [6], Gur and Oktayoglu, [18]) and the development of symptoms (Becker and Schweinhardt, [14]), though more research in this area is needed.

Dietary behaviors

There is an increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia (Campagnolo et al. [19]; Rita-Silva et al. [20]) and patients commonly reported food intolerances and used eliminations diets (Trabal et al. [21]; Slim, Calandre and Rico- Villademoros, [22]; Campagnolo et al. [19]). Goedendorp et al. [23] found that most CFS/ME patients had an unhealthy diet with low intake of fruit, vegetables and fibre, and high intake of saturated fat, though some healthy adjustments were made as alcohol intake was low in CFS/ME (Woolley, Allen and Wessely, [24]) and fibromyalgia patients (Ruiz-Cabello et al. [25]). It is therefore plausible that healthy dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet could counter some of these nutritional, deficiencies and underlying imbalances such as inflammation and oxidative stress, and improve symptoms (Brown [26]).

Multi-disciplinary therapy

There are no disease modifying treatments for CFS/ME (NICE, [9]) or fibromyalgia (Tzellos et al. [27]), so medications focus on managing symptoms using anti-depressants, analgesics and sedatives (NHS, [28], 2019a), therefore, non-pharmacological treatments such as nutrition are of interest. As these diseases exhibit many physical and psychological symptoms, it is unlikely that nutrition will work in isolation and multidisciplinary therapy (MDT) has been developed. Meta-analysis has shown MDT was effective in improving pain, function, fatigue and depressed mood in fibromyalgia patients and The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) in Germany recommended MDT consisting of patient education, patient-centred communication, aerobic exercise, CBT and a vegetarian diet (Häuser, Thieme and Turk, [29]). The American Pain Society (APS) also recommended combining two or more non-pharmacologic therapies including patient education, CBT, aerobic exercise and acupuncture, though they did not recommend nutrition due to a lack of sufficient research (American Pain Society, [30]). More evidence was required regarding the benefits of MDT in CFS/ME as conflicting results were found by two RCTs. Taylor [31], demonstrated a significant effect on disease impact and quality of life in the intervention group, when compared with delayed programme controls. By contrast, Pinxsterhuis et al. [32] found no significant differences in functioning and symptoms between the intervention group and usual care. A brief literature review of the components of MDT for CFS and fibromyalgia follows.

Nutrition

There was weak evidence that nutritional interventions improved symptoms of fibromyalgia. Systematic reviews showed low Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols (FODMAP), hypocaloric, vegan and vegetarian diets significantly improved pain, fatigue, physical functioning, sleep, mental health and quality of life in fibromyalgia patients (Rossi [33]; Rita-Silva [20]; Lowry [34]; Pagliai [35]). Though many of the RCTs in these reviews were small, of poor statistical quality and did not assess pre- and post-dietary intake of participants, which made it difficult to draw strong conclusions. Several studies have found anti-inflammatory diets improved fatigue, pain, anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia (Ruiz-Cabello [25]; Correa-Rodríguez et al. [36]; Köroğlu and Adigüzel, [37]; Tomaino et al. [38]. Mengshoel et al. [39] was also able to show that dietary changes in fibromyalgia patients were associated with reductions in pain intensity, however the authors were over-ambitious in their claims as this was a pilot study with no control. A systematic review found indicative evidence that an anti-inflammatory diet improved fatigue in CFS/ME patients (Haß, Herpich and Norman, [40]) and further research was required to validate these findings.

Exercise

Numerous studies have found exercise was an effective treatment for fibromyalgia (Häuser et al. [41]; Bidonde et al. [42]; Sosa-Reina et al. [43]), and aerobic exercise was recommended in American and German fibromyalgia guidelines (Häuser, Thieme and Turk, [29]). Two studies found MDT led to a significant increase in exercise (Anderson and Winkler, [44]) and fitness (Bailey et al. [45], and Lemstra and Olszynski, [46] demonstrated exercise adherence in an MDT was associated with improvements in pain in fibromyalgia. Post-exertional fatigue was a common symptom of CFS/ME, therefore exercise was not typically recommended for these patients (Sandler, Lloyd and Barry, [47]; NICE, [48]) as it was possible that physical stress exacerbated underlying inflammatory and oxidative pathopsychological anomalies (Maes and Twisk, [32]. The varying response to exercise between fibromyalgia and CFS/ ME patients demonstrates the requirement to personalise the MDT to the needs of the individual.

Relaxation and Stress Management

Relaxation and stress management interventions teach relaxation using techniques such as mindfulness and guided imagery. Systematic reviews by Lauche et al. [49], Haugmark et al. [50] and Lakhan and Schofield, [51] found that mindfulness had a small, short-term effect on pain, fatigue, anxiety, quality of life and daily functioning in fibromyalgia. Meeus et al. [52] found moderate evidence that guided imagery reduces pain in CFS/ ME and fibromyalgia patients. In addition, Poole and Siegel, [53] found strong evidence relaxation techniques improved pain, daily functioning and pain in fibromyalgia, however this review should be assessed with caution due to heterogeneity of the reviewed studies. Further research is needed to assess whether adherence to relaxation techniques can improve long term outcomes for fibromyalgia and CFS patients.

Psychological interventions

There was strong evidence from meta-analysis that CBT was effective in reducing symptoms and disability of fibromyalgia (Bernardy et al. [54]), and American and German treatment guidelines recommended CBT for fibromyalgia (Häuser, Thieme and Turk, [29]). There was moderate evidence that CBT was moderately effective in improving symptoms of CFS/ME (Malouff et al. [55]; Castell, Kazantzis and Moss-Morris, [56]), however CBT maybe more effective in CFS/ME patients who are also suffering from anxiety or depression (Castell, Kazantzis and Moss-Morris, [56]).

There was conflicting evidence whether peer counselling was effective at reducing disease impact in CFS/ME. Taylor [31] showed an eleven-month MDT, including peer counselling was effective at improving quality of life in CFS/ME. This differs from the findings presented by Pinxsterhuis et al. [32] who evaluated a sixteen-week programme that included peer counselling and found no significant differences in functioning and symptoms between the intervention group and usual care in CFS/ME. There are still many unanswered questions about the efficacy of peer counselling in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia demonstrating a gap on research.

Internet based interventions

There was significant interest in Internet based interventions as they could be an inexpensive alternative to face-to-face treatment for chronic disease (Young et al. [57]). Johnston, Staines and Marshall-Gradisnik, [58] found that a significant proportion of CFS/ME and fibromyalgia patients were housebound and such interventions may overcome accessibility barriers (Castro- Marrero, Faro, et al. [5]). Arroll et al. [59] found weak evidence that an online MDT was effective at improving fatigue and sleep difficulties in CFS/ME, though these findings should be interpreted cautiously as group allocation was not randomised and there were differences between the groups at baseline. Browne et al. [60] found that face to face counsellor sessions and Internet programs could both be effective in changing dietary behaviour in adults with chronic disease, however a systematic review found that practitioner support made the Internet interventions more effective (Hou, Charlery and Roberson [61]). This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of MDT with an Internet programme and individualized Internet and video consultations on changing dietary and lifestyle behaviors and improving symptoms and disease impact in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia patients. This study critically evaluated any associations between dietary and lifestyle changes and symptom improvements.

Methodology

Intervention

The MDT was developed by a UK private company “The Chrysalis Effect” and is an Internet based biopsychosocial programme with modules on nutrition, endocrinology, mental health, lifestyle, relationships, and exercise. New content was emailed every fortnight to participants and in the intervening weeks a touch-based video summarized what was taught. There was also a library of webinars, meditations, and wellbeing exercises. The Internet programme was provided to participants free of charge and participants had the additional option of seeing a Nutritional Therapist or Peer Counsellor via video consultation, at their own expense.

The nutritional recommendations were:

a) Eat more fresh fruit and vegetables, ideally 50% of the plate.

b) Eat more wholegrains

c) Eat more lean meat, fish and seafood.

d) Eat more beans and pulses.

e) Cut out processed foods.

f) Cut out sugar and refined carbohydrates.

g) Reduce caffeine intake.

h) Reduce alcohol intake.

i) Avoid foods of intolerance e.g. gluten and dairy.

The lifestyle recommendations were:

a. Walking and meditative movement

b. Spend less time watching television and on smartphones and tablets

c. Wellness exercises

d. Mindful meditation

e. Relaxing hobbies e.g. chess, fishing, reading, craft or art

Procedure

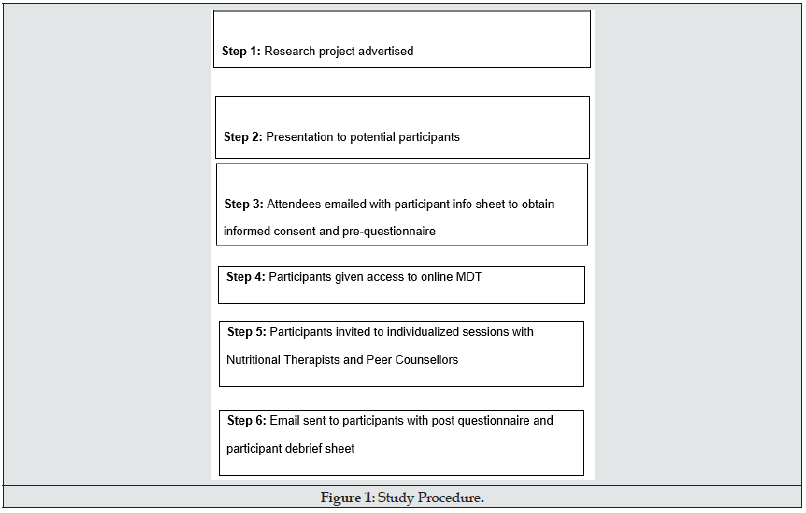

A before and after study was chosen to measure dietary and lifestyle behaviors, symptoms and disease impact at baseline and three months. Approval was granted by the University of Worcester Ethics Committee (University of Worcester, [62]) before participant recruitment and data collection commenced. Referrers between September and October 2020 were invited to a presentation about the MDT and the research programme (Figure 1). The participant information sheet was then emailed to attendees with a link to give informed consent and the questionnaire. Participants were given free access to the MDT and no financial incentives were offered. Participants could withdraw from the study at any time until the post-questionnaire was completed. Compliance with General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 was ensured.

Participants

Participants were following an Internet based MDT “The Chrysalis Effect Recovery Programme” in their homes in the UK. Data was collected at the beginning and on completion of the threemonth programme, at the time that participants were involved in the programme between November 2020 to March 2021. All participants were private referrers to the Chrysalis Effect, and to be eligible for this study they had to have a medical diagnosis of CFS/ME or fibromyalgia and be 18 or over. Participants were in two groups, based on personal preference:

1. Non Individualized Internet programme

2. Individualized Internet programme plus video consultations with a Nutritional Therapist or Peer Counsellor

There was no control group, and several confounders were not controlled for including severe mental health disorders (Hamnes et al. [63]), learning disabilities (Bailey et al. [45]), ability to participate in the programme consistently (Bailey et al. [45]; Anderson and Winkler, [44]) or other treatments (Lacour et al. [64]), which may limit the applicability of the results (Denscombe, [65]). Participants should be representative of the CFS/ME and fibromyalgia population, however as self-referrers there may be some sampling and nonresponse bias, which may limit generalisation. A recruitment target of 25 was set and 26 participants were recruited, however only 18 completed both questionnaires, which may limit the statistical significance of the results.

Measures

All study participants were sent a demographic questionnaire and a questionnaire to measure dietary and lifestyle behaviors, disease impact, symptoms and anxiety at the start and end of their involvement in the three-month programme. The description of the measures is as follows:

Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR)

Patients with CFS/ME and fibromyalgia have many symptoms (Spaeth, [66]; Hunter, Paxman, and James, [67]), so whilst CFS/ ME is characterised by fatigue and fibromyalgia by pain these two outcomes were insufficient to measure disease impact (Hickie et al. [68]). The FIQR was developed for fibromyalgia and reports against all the common symptoms of CFS/ME; musculoskeletal pain/ fatigue, neurocognitive difficulties, sleep and mood disturbance (Hickie et al. [68]) and so is relevant for both conditions. It is a 21-item questionnaire which assesses patients’ functional ability, symptoms, and overall impact of the disease on their daily lives. The first nine questions measure functional ability to perform daily tasks on a Likert scale. The next two items relate to the overall impact on the subject’s daily life. The last ten items evaluate symptoms such as pain, energy and stiffness and are measured by a Likert scale. The three sub-sections of function, overall impact and symptoms are added together to give sub-domain scores and then a simple scoring algorithm is applied to produce a total FIQR score. A higher score on the FIQR indicates a greater impact of disease and a lower score demonstrates reduced disease impact. The FIQR was an updated version of the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ) with a simpler scoring algorithm (Bennett et al. [69]) and shows good concurrent validity with the FIQ (r = 0.88, P < 0.001) (Bennett et al. [69]). The FIQR may be completed in less than two minutes (Physiopedia [70]), is frequently used to measure outcomes in RCTs and can detect change (Williams and Arnold, [71]).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression – Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A)

Anxiety is often co-morbid with CFS/ME and fibromyalgia (Schmidt-Wilcke and Clauw, [7]; Dansie et al. [4], and dietary and lifestyle changes may bring improvements (NHS, [72]). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression – Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A) subscale is widely used to measure anxiety in community settings, takes less than five minutes to complete, provides sensitivities and specificities at ~80% and 90% for detecting anxiety disorders, has high construct validity and can detect changes over time (Julian, [73]; Smarr and Keefer, [74]; Pallant, [75]).

Short Food Frequency Questionnaire

A short Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) may be used to measured adherence to the dietary recommendations (Ocké, [76]; Cleghorn et al. [77]; Medical Research Council, [78]) and has good internal consistency and retest reliability (Béliard et al. [79]; Khalesi et al. [80]). The European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC) 130 item FFQ was adapted to create a bespoke short FFQ as it was one of the largest epidemiological studies of nutrition in UK adults (Bingham et al. [81]) and there was a strong correlation between nutrients assessed from the FFQ and weighed records (Bingham et al. [82]). Twenty-two food and drink items recommended by the CERP were selected from the EPIC FFQ and content validity was ensured via input from the primary gatekeeper and expert panel. The short FFQ asked participants to select how many servings of these foods they had eaten over the last week, on an eight-point scale ranging from ‘never’ or ‘less than once per week’ to ‘6+ portions per day’. Dietary quality indexes such as the Healthy Eating Index may be used to measure adherence to dietary recommendations (Kant [83]), so a bespoke dietary quality score was created. A score of 1-8 was allocated to the frequency scale and each food item was allocated to two categories, ‘recommendation to increase intake’ and ‘recommendation to decrease intake’. If the MDT recommended that participants decrease food intake, the score for that item was reversed and then each item was totalled to give a dietary quality score.

Lifestyle Activities

To simplify the questionnaire and reduce respondent burden (Bowling, [84]), a similar bespoke instrument was used to measure lifestyle activities. A list of the activities recommended in the MDT was created and content validity was ensured via input from the primary gatekeeper and expert panel. A total lifestyle activity score was calculated, considering which activities the MDT recommended to increase or decrease.

Data analysis

Data was collected between October 2020 and March 2021 using JISC Online Surveys, extracted into Excel and data from the pre- and post-questionnaires was matched using the unique reference ID. Negatively worded items in the HADSA scale were reversed (Julian, [73]) and a total anxiety score was calculated. FIQR domain scores were calculated for symptoms, overall impact, and function, and the total FIQR score was calculated (Bennett et al. [85]). Where the MDT recommended a decrease in food and drink items or lifestyle activities, the scores were reversed and then scores were calculated for food, drink, and lifestyle quality. A total dietary quality score was calculated from adding the food and drink quality scores. The change between pre and post testing was calculated for each score.

The data was then transferred to the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS v27) software to be coded, checked for errors and the ‘excluded cases pairwise’ option selected for missing data (Pallant, [75]). Participants who did not complete the posttest questionnaire were removed, as analysis presented in the results chapter indicated there were no significant differences between responders and non-responders (Pallant, [75]). Internal consistency of all composite scales was calculated using Cronbach’s Alpha (Béliard et al. [79]; Khalesi et al. [50]) and these findings are also reported in the chapter. Descriptive statistics provided summaries of the participants characteristics and determined whether findings could be generalized to CFS/ME and fibromyalgia patients (Riffenburgh, [86). “Frequencies” summarized the categorical data and “Descriptive” was used to calculate the mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis of the continuous variables (Pallant, [75]; Field, [87]). “Explore” was used to assess normality by producing Histograms, normal probability plots and boxplots to detect outliers and determine whether the data was skewed and informed the choice of tests (Pallant, [75]). This statistical analysis is presented in the results chapter, however non-parametric tests were selected as not all continuous data was normally distributed (Field, [87]).

The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was selected to explore the differences between pre-test and post-test data for the disease impact, anxiety, dietary quality, and lifestyle activity scales. Mann Whitney U was then used to examine the differences in scores for categorical variables including mode of delivery and type of diet (Pallant, [75]) and effect sizes were calculated (Field, [87]). Scatterplots were created to examine if there was a relationship between health outcomes and dietary and lifestyle quality scores (Field, [87]). The Spearman Rank Order Correlation was then calculated to examine the strength of any relationships (Pallant, [75]).

Results

Participant Characteristics

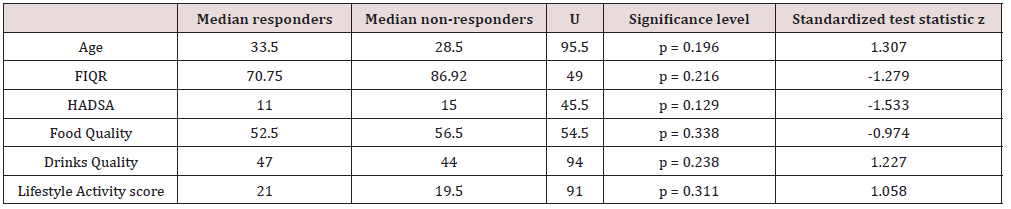

Twenty-six participants completed the pre-questionnaire and 18 the post-questionnaire (7 non-responders and 1 dropped out due to hospitalization), giving a drop-out rate 31%. Pre-test scores were examined using Mann Whitney U and there were no statistically significant differences at baseline between responders and non-responders (Table 1), so non-responders were removed.

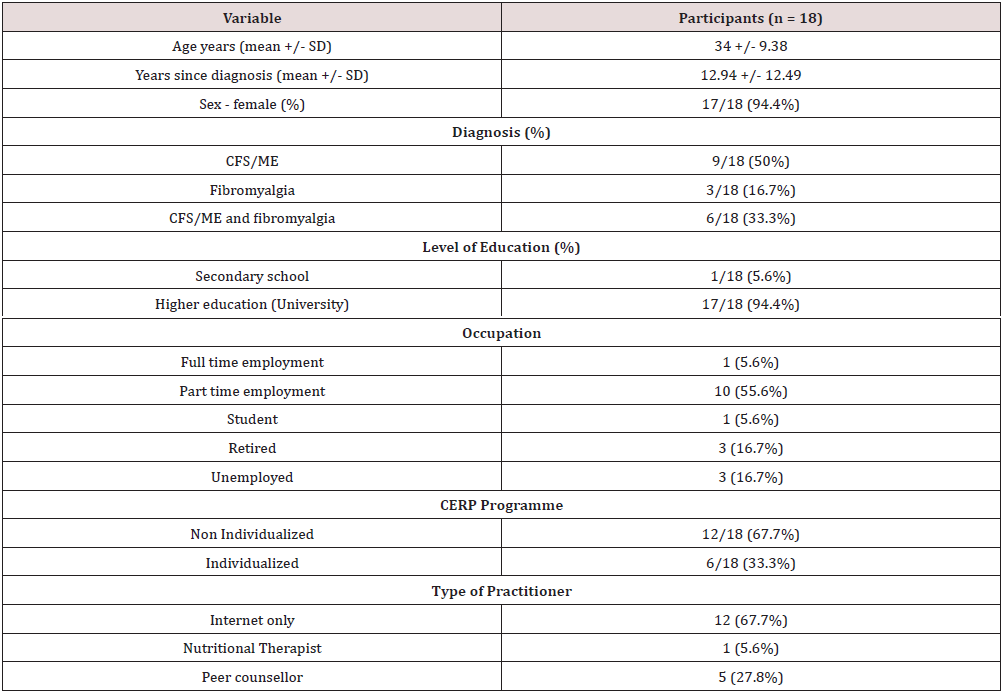

Age ranged from 18 to 53, with a mean of 34 years and the mean length of time since diagnosis was 13 years. There were nine participants with a diagnosis of CFS/ME, three with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia and six with a diagnosis of both CFS/ME and fibromyalgia (Table 2). Most subjects were University educated (94.4%) and worked part time (55.6%). There were 12 participants in the non-individualized Internet group and six participants in the individualized group, where one participant worked with a Nutritional Therapist and five participants worked with Peer Counsellors.

Reliability of Scales

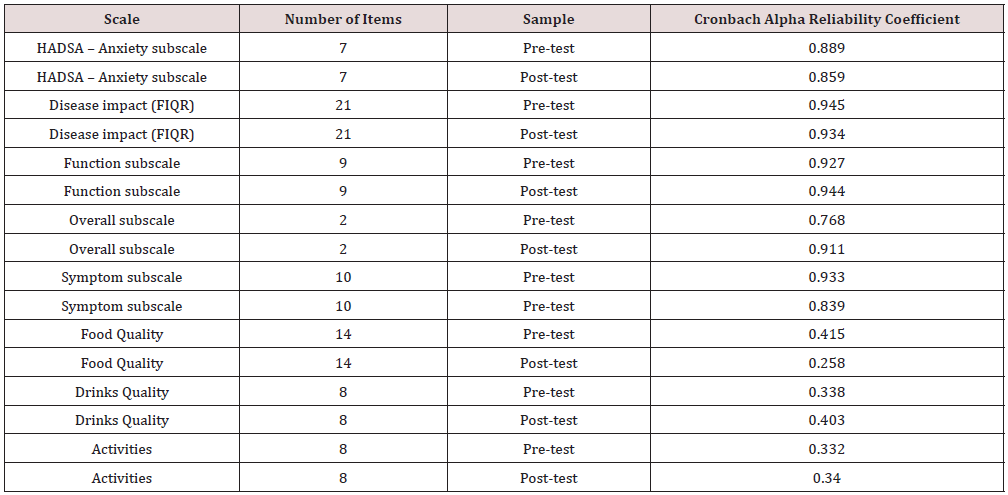

Internal consistency of all composite scales was calculated using Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient (Table 3) and for disease impact (FIQR) and anxiety (HADSA) the coefficients were above 0.8 which was a good level (Field, [87]). The coefficients for the Food Quality, Drinks Quality and Lifestyle Activities scales were below 0.7 which was too low to be acceptable (Pallant, [75]), so this data will be interpreted with caution.

Changes in Symptoms, Function and Disease Impact

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in disease impact (FIQR) at three months follow up, z = 2.461, p < 0.014, with a moderate effect size (r = .41) (Cohen, [88]). The median score for disease impact decreased from pre-test (Md = 70.50) to post-test (Md = 53.83) (Table 4). There was a statistically significant improvement in the symptoms sub-scale at three months follow up, z = 2.745, p < 0.006, with a moderate effect size (r = .45). The median score for symptoms decreased from pre-test (Md = 73.50) to post-test (Md = 56.50). There were no significant differences in the function and overall impact subscales at pre-test and post-test.

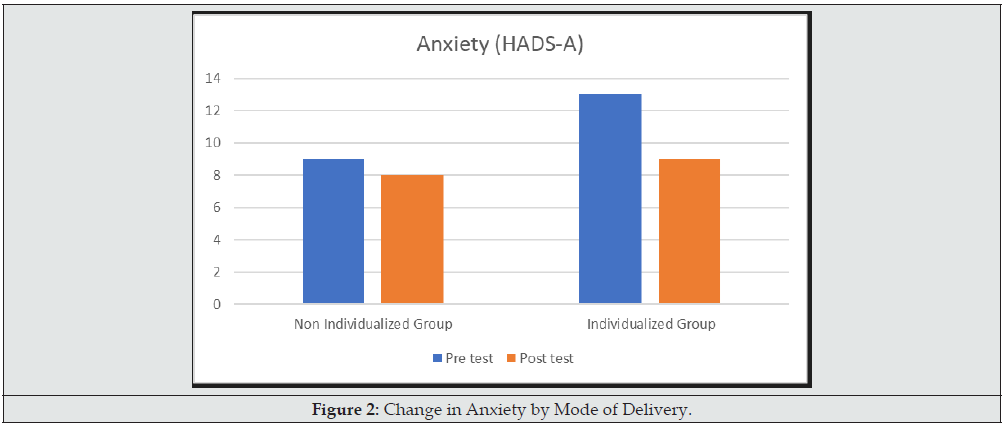

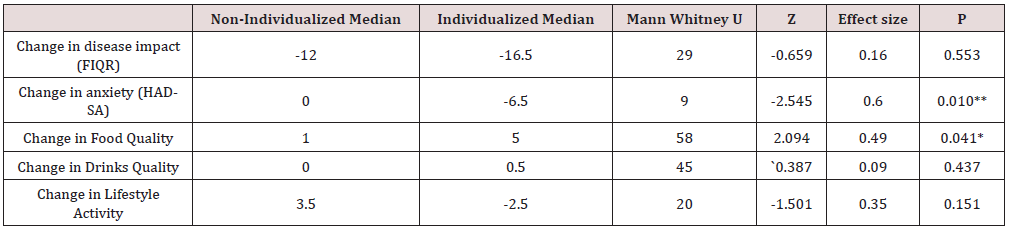

Changes in Anxiety

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in anxiety (HADS-A) at three months follow up, z = 2.048, p < 0.041, with a moderate effect size (r = .34) (Cohen, [88]). The median score for anxiety decreased from pre-test (Md = 11.00) to post-test (Md = 8.00) (Table 4). A Mann Whitney U Test revealed that subjects in the Individualized group had statistically significantly reductions in Anxiety (Md -6.5, n = 6), whilst those in the Non-Individualized group did not change (Md = 0, n = 12) , U = 9.0, z = -2.545, p > 0.01, r = .60 (Figure 2) (Cohen, [88]).

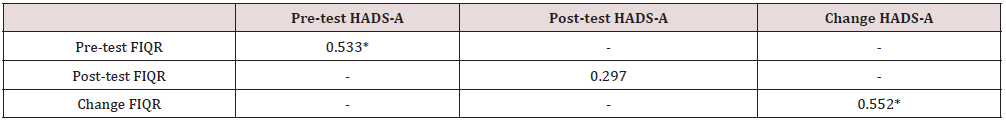

The relationship between disease impact (as measured by FIQR) and anxiety (as measured by HADS-A) was investigated using scatterplots and the non-parametric Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficient. At pre-test there was a strong positive correlation between the two variables rho = 0.533, n = 18, p < 0.023, with higher levels of disease impact associated with higher levels of anxiety (Table 5). There was a strong positive correlation between the change in disease impact (as measured by change in FIQR) and change in anxiety (as measured by change in HADS-A), rho = 0.552, n = 18, p < 0.018, with a decrease in disease impact associated with a decrease in anxiety (Table 5).

Changes in Dietary Behaviors

At baseline more than two thirds of participants (72%) were following a special diet including gluten free (39%), diary free (33%) and high protein (17%). After three months, there was an increase in those on a special diet (79%), with gluten free unchanged (39%) and increases in diary free (39%) and high protein (22%).

The proportion of participants consuming fruit (pre-test 56%, post-test 67%) and vegetables (pre-test 67%, post-test 89%) at least once per day increased at three months. In addition, the proportion of subjects eating pulses at least once per week increased (pre-test 39%, post-test 50%). There were no changes in the proportion of participants eating wholegrain bread/pasta/rice at least once per day (pre-test 22%, post-test 22%). In addition, there were no changes in the number of subjects consuming alcohol once a week or less (pre-test 100%, post-test 100%). At three months the proportion of subjects consuming chocolate and sweets (pre-test 33%, post-test 11%) and tea/coffee with caffeine (pre-test 44%, post-test 27%) at least once per day had decreased. Also, the proportion of participants eating ready meals/takeaways once a week or less decreased (pre-test 100%, post-test 89%). In addition, the proportion of participants eating fish (pre-test 61%, post-test 55%) and lean meat (pre-test 72%, post-test 33%) at least twice per week decreased.

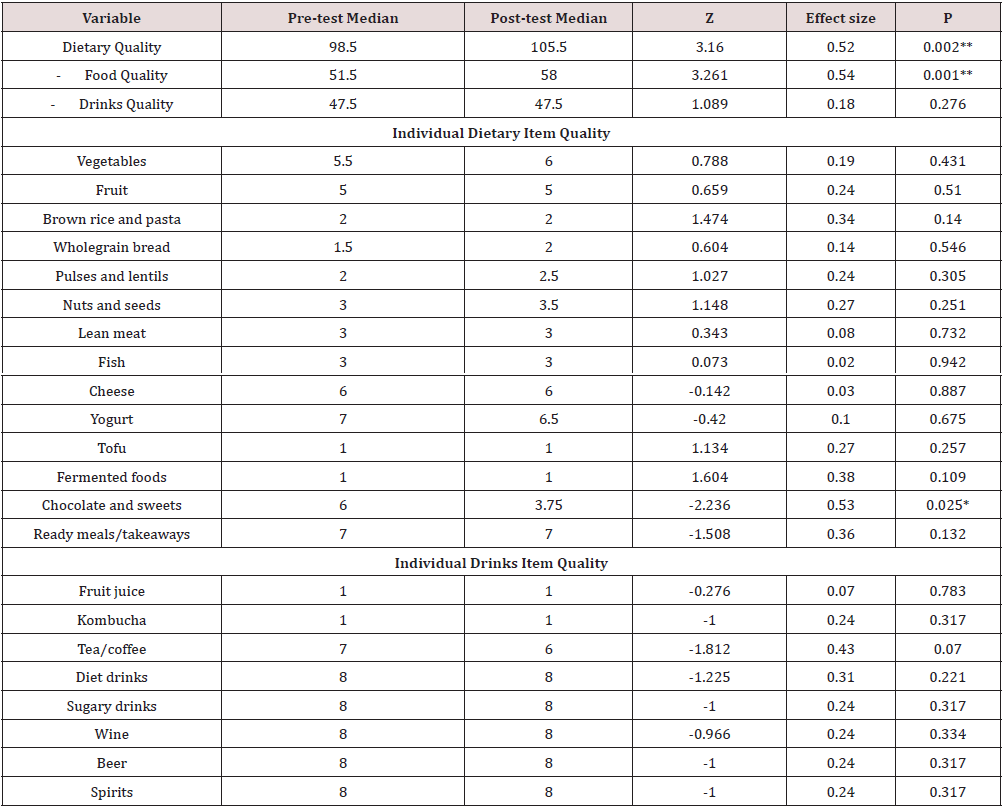

Changes in Dietary Quality Scores

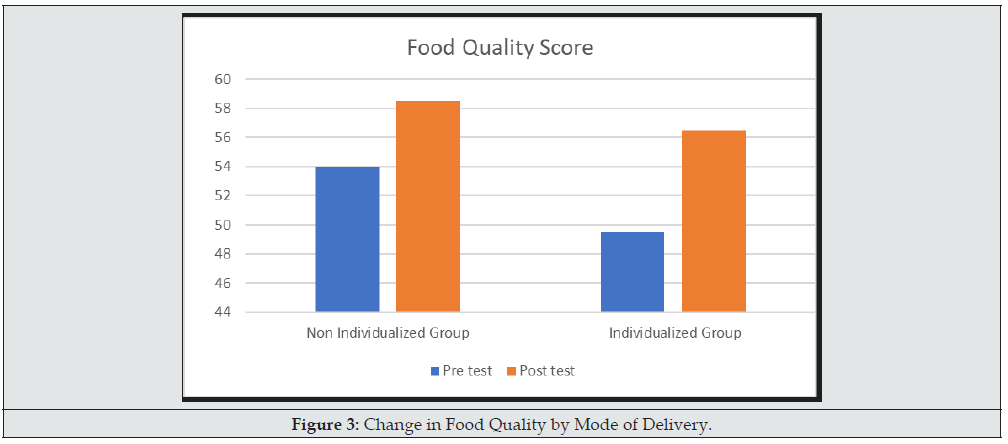

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in total dietary quality at three months follow up, z = 3.16, p < 0.002, with a large effect size (r = .52). The median score of the dietary quality index increased from pre-test (Md = 98.5) to post-test (Md = 105.5) (Table 6). In addition, there was a statistically significant improvement in food quality at three months follow up, z = 3.261, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (r = .54). The median score on the food quality index increased from pretest (Md = 51.5) to post-test (Md = 58.0). There were statistically significant reductions in intake of chocolate and sweets, z = -2.236, p < 0.025, with a large effect size (r = .53). The median score for the intake of chocolate and sweets decreased from pre-test (Md = 6.0) to post-test (Md = 3.75). There were no significant changes in drinks quality.

A Mann Whitney U Test revealed subjects in the Individualized group had statistically significantly more improvements in Food Quality (Md 5, n = 6) than those in the Non-Individualized group (Md = 1, n = 12) , U = 58.0, z = 2.094, p > 0.04, r = .49 (Table 7) (Figure3) (Cohen, [88]).

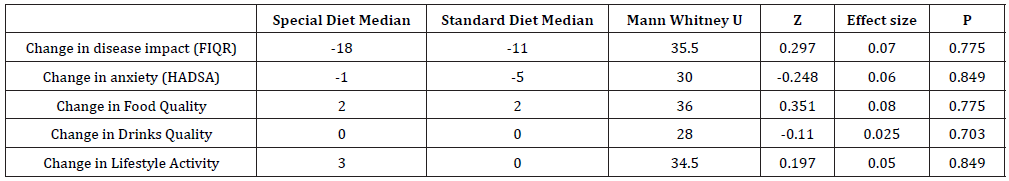

There were no significant differences in food or drinks quality between those who followed a special diet and those on a standard diet (Table 8).

Changes in Lifestyle Activities

The most common weekly activity was mindful meditations (pre-test 72%, post-test 83%). There were increases in the number of participants doing weekly wellness exercises (pre-test 39%, post-test 72%), gentle exercise (pre-test 61%, post-test 78%) and relaxing hobbies (pre-test 72%, post-test 78%). There was no change in the proportion of subjects doing meditative movement weekly. The proportion of subjects watching television everyday deceased (pre-test 94%, post-test 67%), as did those using their mobile phone daily (pre-test 100%, post-test 95%). There was no change in the proportion of subjects using their computer or tablet.

Changes in Lifestyle Quality Scores

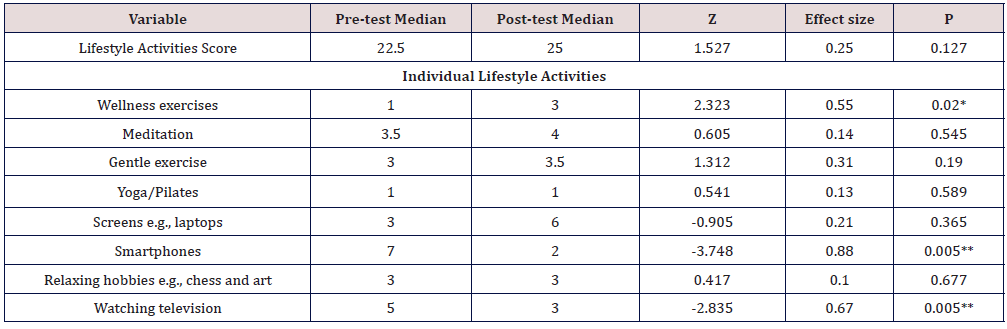

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test demonstrated significant increases in wellbeing exercises at three months follow up, z = 2.323, p < 0.02, with a large effect size (r = .55). The median score for wellness exercises increased from pre-test (Md = 1.0) to post-test (Md = 3.0) (Table 9). It revealed a significant decrease in smartphone usage, z = -3.748, p < 0.005, with a large effect size (r = .88). The median score decreased from pre-test (Md = 7.0) to post-test (Md = 2.0). In addition, the score for watching television decreased significantly, z = -2.835, p < 0.005, with a large effect size (r = .67). The median score decreased from pre-test (Md = 5.0) to post-test (Md = 3.0), however the total lifestyle activity quality score did not increase significantly.

Associations between Dietary Changes and Health Outcomes

The relationship between changes in dietary quality and individual dietary items (as measured by short FFQ) and disease impact (as measured by FIQR) and anxiety (as measured by HADS-A) were investigated using scatterplots and the non-parametric Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficient. There was a strong negative correlation between the change in fruit intake and change in anxiety, rho = 0.610, n = 18, p < 0.007, with an increase in fruit intake associated with a decrease in anxiety (Table 10). There was a strong negative correlation between change in fruit juice intake and FIQR, rho = - 0.499, p < 0.035, with increasing fruit juice intake associated with a decrease in disease impact. There were no significant correlations between changes in overall dietary, food, or drinks quality with health outcomes.

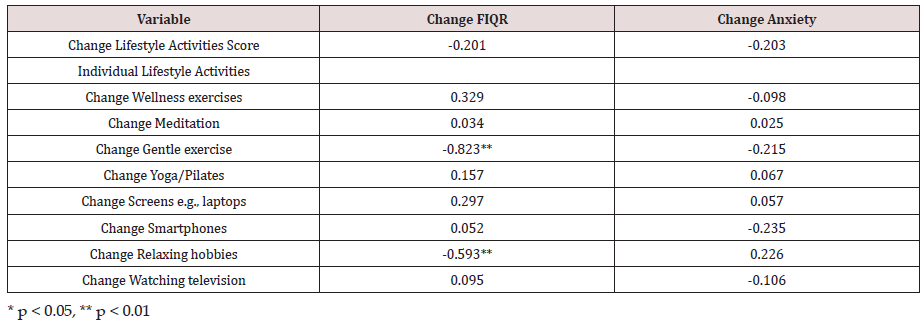

Associations between Lifestyle Changes and Health Outcomes

The relationship between changes in lifestyle activities score and individual lifestyle activities and disease impact (as measured by FIQR) and anxiety (as measured by HADS-A) were investigated using scatterplots and the non-parametric Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficient. This revealed a strong negative correlation between change in gentle exercise and disease impact rho = -0.823, n = 18, p > 0.0005 (Table 11). An increase in gentle exercise was associated with a decrease in disease impact. Spearman’s rank order correlation also demonstrated a strong negative correlation between change in hobbies and disease impact rho = -0.593, n = 18, p > 0.01. An increase in relaxing hobbies was associated with a decrease in disease impact. There were no significant correlations between the change in total lifestyle activity score and health outcomes.

Discussion

Disease impact

This study found that there was a significant improvement in FIQR after three months, indicating a reduction in disease impact, which is consistent with MDT studies by Anderson and Winkler, [44], Bailey et al. [45] and Lacour [64] in fibromyalgia and Arroll and Howard [89], in CFS/ME. Though a note of caution is due here since this was a pilot study and there was no control group. The average reduction in mean FIQR was 17%, which was below the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of 45.5% or 27 points (Surendran and Mithun,[90]. Only two participants reported changes of more than 45.5%, therefore despite producing significant improvements the MDT did not achieve a MCID at three months. Lacour et al. [64] found that MDT took eight months to significantly improve FIQR therefore longer intervention and follow up is needed.

Symptoms

There was a significant improvement in the FIQR symptom subdomain at three months and this result corroborates the findings of much of the previous work on MDT in fibromyalgia where subjects saw improvements in pain (Mengshoel et al. [39]; Bailey et al. [45; Lemstra and Olszynski, [46]; Anderson and Winkler [3], and reduced their medication (Lemstra and Olszynski, [46]). The APS and AWMF recommend MDT as a primary treatment (Häuser, Thieme and Turk [29]), however meta-analysis has shown improvements in pain were not necessarily sustained in the long term (Häuser et al. [91]), so longer follow up is required. This study supports evidence from previous pilot studies (Gibson and Gibson, [92]; Arroll and Howard, [13]; Arroll et al. [59]) and one RCT (Taylor, [31]) that MDT improves symptoms in CFS/ME patients. This outcome was contrary to Pinxsterhuis et al. [32] who found MDT did not have an effect on symptoms when compared with standard care. As the research to date has mainly been pilot studies, well controlled RCTs are needed to validate the findings of this study in CFS/ME patients.

Anxiety

At baseline the median HADS-A score was 11 and 67.7% of participants scored ≥9, indicating most subjects probably had a moderate anxiety disorder (Julian, [73]; Smarr and Keefer, [74]). After three months there was a significant improvement in HADS-A and 38.9% of participants scored ≥9, suggesting anxiety had reduced considerably to a normal to mild level. This finding broadly supports the work of other studies in this area, which have shown MDT may significantly improve anxiety in CFS/ME (Gibson and Gibson, [92]; Lacour et al. [64] and fibromyalgia (Anderson and Winkler, [44]). Subjects in the individualized group showed significantly more improvements in anxiety than those in the non-individualized Internet group and this supports the findings of Taylor, [31] that Peer Counsellors were effective at improving symptoms of CFS/ME. A possible explanation for this maybe that the practitioners were specially trained to support patients with CFS/ME and fibromyalgia (The Chrysalis Effect, [93]) and the practitioners have suffered from these conditions.

Dietary behaviors

One unique aspect of this study was to examine the dietary and lifestyle behaviours of participants and ascertain whether they made changes, as adherence to dietary recommendations was not commonly measured in MDT studies (Pagliai et al. [35]). This study confirms the findings of Trabal et al. [21] that a high proportion of CFS/ME and fibromyalgia patients were following gluten free (pre-test and post-test 39%) or dairy free (pre-test 33%, post-test 39%) diets. This study supports evidence from previous observations (Goedendorp et al. [23]; Ruiz-Cabello et al. [25]) that CFS/ME and fibromyalgia patients consume low levels of fruit, vegetables and fibre, with few participants consuming five portions of fruit and vegetables per day (pre-test 22%, post-test 28%), and intake of wholegrains was low. In addition, this research corroborates the findings of a great deal of previous work (Woolley, Allen and Wessely, [24]; Goedendorp et al. [23]; Ruiz-Cabello et al. [25]) which demonstrates alcohol intake was low in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia, with all subjects drinking alcohol once a week or less. One unanticipated finding was that participants consumed few ready meals/takeaways, as it was hypothesized intake would be higher due to levels of fatigue and disability. Similarly, most participants had a low intake of sugary carbonated drinks, and one possible explanation may be subjects wanted to avoid unhealthy and ultra-processed foods.

Changes in Dietary Quality

This study found the MDT significantly improved total dietary quality and food quality, and this was important as few previous studies have measured dietary intake and established whether subjects made dietary changes. This was consistent with Mengshoel et al. [39] who found that 44% of participants improved their diet, though the authors did not detail the dietary changes. This study supports evidence from Hou, Charlery and Roberson [61] that combining Internet programmes with practitioner support was more effective than Internet only interventions at changing dietary behaviour and a possible explanation may be that the practitioner provided enhanced patient education, feedback, and monitoring. In addition, low engagement and retention were well known problems with Internet based interventions (Young et al. [94] and the additional input from a practitioner may have increased attention, comprehension, and motivation.

Lifestyle Activities

Three different lifestyle measures showed improvements after three months, with significant increases in wellbeing exercises and significant decreases in smartphone usage and watching television. These results were in agreement with those obtained by Mengshoel et al. [39] who found that 50% of subjects were doing relaxation exercises at ten weeks.

Associations between dietary and lifestyle changes and health outcomes

This study did not find any significant correlations between changes in overall dietary quality and any health outcomes. One possible explanation could be the nutritional recommendations were not the most effective to improve symptoms of CFS/ME or fibromyalgia. There is weak evidence alternative diets such as vegan/vegetarian, hypo-calorific diets, anti-inflammatory and low FODMAP may reduce symptoms such as pain, fatigue and anxiety in fibromyalgia (Rossi et al. [33]; Rita-Silva et al.[20]; Pagliai et al. [35]). A second possible explanation is the dietary intervention required a longer duration, as previous research has found following a hypo-calorific or vegetarian diet for between five to seven months resulted in symptom improvements (Rita-Silva et al. [95]). A third possible explanation could be the nutritional intervention required higher intensity, as there was only one module in the thirteen-week programme dedicated to nutrition and previous studies have shown repeated contact increases effectiveness of dietary interventions (Greaves et al. [96]). Finally, the reliability of the dietary quality scale was low, so caution should be taken when interpreting these associations There was a strong negative association between increasing fruit intake and decreasing anxiety and increasing fruit juice intake and decreasing disease impact. This was consistent with findings from Ruiz-Cabello et al. [25] that daily consumption of fruit was associated with significant improvements in depression in fibromyalgia. These relationships may partly be explained by nutrients in fresh fruit such as anti-oxidative vitamins, which may mitigate the pro-inflammatory state of these patients and provide symptom relief in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia (Sanada et al. [97]; Haß, Herpich and Norman, [40]), though more research on the benefit of fruit and anti-inflammatory diets in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia is needed.

This study found a strong correlation between an increase in gentle exercise such as walking and a decrease in disease impact. A strong association between exercise and symptom improvements was found by Lemstra and Olszynski [40], who showed patients with fibromyalgia who exercised had larger improvements in disease impact and depression and used less medication than those who did not exercise.

These findings were corroborated by meta-analysis, which found moderate evidence that exercise leads to clinically significant improvements in quality of life, pain, and function in fibromyalgia (Häuser et al. [41]; Bidonde et al. [70]; Sosa-Reina et al. [43]). What was unexpected was gentle exercise had a significant association with health outcomes in both fibromyalgia and CFS/ME patients as exercise was not recommended in CFS/ME (NICE, [98]). Participants in this study saw modest increases in gentle exercise from on average 2-4 times per week at baseline, to 5-6 times per week at three months. One possible explanation for the positive association between gentle exercise and symptom improvements maybe the participants were able to pace themselves as the exercise was not too rigorous.

One unique finding of this study was an increase in hobbies such as chess, art and crafts were strongly associated with improvements in disease impact. One possible explanation for these findings was these hobbies contribute to relaxation and stress management (Riley, Corkhill and Morris, [78]). No previous studies have found any correlations between those taking up these hobbies and improvements in health outcomes in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia. One RCT by Baptista et al. [99] found an art therapy programme showed significant improvements in functioning, symptoms, and emotional wellbeing, but as this involved attending group sessions with an art therapist it was not a strong comparison. Further research into the benefit of these hobbies in CFS/ME and fibromyalgia is needed.

Limitations

There were several limitations, foremost being the small sample, which may lead to selection bias as participants may not be representative of the population (Edwards, [30]). There was no control group, group allocation was not randomized and possible confounders such as co-morbidities were not controlled for (Kumar, [52]), which may make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions (Denscombe, [65]). In addition, a short FFQ and dietary and lifestyle quality scores were created. Best practice would be to validate these instruments against a food diary before commencing research (Béliard et al. [79]; Khalesi et al. [80]) but there was insufficient time.

Recommendations for Nutritional Therapy practitioners

Nutritional Therapists are recommended to assess the diet of patients with CFS/ME or fibromyalgia as whilst they made some healthy choices such as reducing intake of alcohol and some ultraprocessed foods, their dietary intake of fresh fruit, vegetables, fibre and fish was low. Patients could benefit from personal dietary advice to reduce disease impact and symptoms, and focus should be given to increase fruit and vegetable intake and decrease intake of sweets and chocolate. In light of this study, and findings by Pagliai et al. [35] and Tomaino et al. [38], consideration should be given to educating clients about the benefits of anti-inflammatory diets such as the Mediterranean Diet.

This study has demonstrated the benefit of the biopsychosocial model, which emphasizes a holistic approach so Nutritional Therapists should assess the clients’ lifestyle and if appropriate encourage them to take up gentle exercise and manage stress through relaxing hobbies. This research demonstrates both Internet programmes and video consultations may be beneficial, so Nutritional Therapists could consider developing Internet services as these may be cost-effective and accessible for home bound clients.

Recommendations for further research

Questions remain about the effectiveness of this Internet based MDT and a well-controlled RCT with a larger sample, longer duration and follow up is needed. Further work is also required to establish the cost effectiveness of the MDT including whether it reduces the cost of medical care and improves work status. New content was released fortnight and to understand which modules are having the most impact studies are needed that measure engagement and attrition. Qualitative studies could also explore the experiences of participants.

Conclusion

This study found early evidence that improvements in disease impact, symptoms and anxiety may be achieved in these mostly unresponsive chronic conditions through a low-cost, Internet based multidisciplinary intervention. It also found that whilst many CFS/ME and fibromyalgia patients consumed low levels of vegetables, fruit, fibre, and fish, they had some aspects of a healthy diet as they consume low levels of alcohol, ready meals, takeaways and sugary drinks. In addition, this study found indicative evidence that eating more fruit, taking up a relaxing hobby and doing more gentle exercise reduced the impact of these diseases and improved anxiety.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those who took part in this study, Professor Derek Peters at the University of Worcester and Elaine Wilkins and Kelly Barnes at the Chrysalis Effect Recovery Programme.

References

- Abbi and Natelson (2013) Is chronic fatigue syndrome the same illness as fibromyalgia: Evaluating the “single syndrome” hypothesis. QJ Med Oxford Academic pp. 3-9.

- Jones (2015) The Prevalence of Fibromyalgia in the General Population: A Comparison of the American College of Rheumatology 1990, 2010, and Modified 2010 Classification Criteria, Arthritis & Rheumatology 67(2): 568-575.

- Castro-Marrero, Sáez Francàs (2017) Treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis, all roads lead to Rome. British Journal of Pharmacology 174(5): 345-369.

- Dansie (2012) Conditions Comorbid with Chronic Fatigue in a Population Based Sample, Psychosomatics 53(1): 44-50.

- Castro Marrero, Faro (2017) Original Research Report Comorbidity in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study, Psychosomatic Medicine 58(5): 533-543.

- Collin (2017) Trends in the incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in the UK, 2001-2013: a Clinical Practice Research Datalink study, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 110(6): 231-244.

- Schmidt Wilcke, Clauw (2011) Fibromyalgia: from pathophysiology to therapy, Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 7(9): 518-527.

- Lempp (2009) Patients experiences of living with and receiving treatment for fibromyalgia syndrome: A qualitative study, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 10(1): 124.

- NICE (2007) Chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management diagnosis and management Clinical guideline.

- Avellaneda-Fernández (2009) chronic fatigue syndrome: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. BMC psychiatry 9(Suppl 1): 1.

- Clements (1997) Chronic fatigue syndrome: a qualitative investigation of patients beliefs about the illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 42(6): 615-624.

- Puri (2007) Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and the pathophysiology of myalgic encephalomyelitis chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Pathol 60(2): 122-124.

- Myhill, Booth, McLaren Howard (2009) Chronic fatigue syndrome and mitochondrial dysfunction, International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 2(1): 1-16.

- Becker, Schweinhardt (2012) Dysfunctional Neurotransmitter Systems in Fibromyalgia, Their Role in Central Stress Circuitry and Pharmacological Actions on These Systems, Pain Research and Treatment: pp. 741746.

- Glassford (2017) The Neuroinflammatory Etiopathology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Frontiers in physiology 17(8): 88.

- Light (2009) Adrenergic Dysregulation and Pain with and Without Acute Beta-Blockade in Women With Fibromyalgia and Temporomandibular Disorder. Journal of Pain 10(5): 542-552.

- Russell (1994) Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance p in patients with the fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis & Rheumatism 37(11): 1593-1601.

- Gur and Oktayoglu (2008) Central Nervous System Abnormalities in Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: New Concepts in Treatment. Current Pharmaceutical Design 14(13): 1274-1294.

- Campagnolo (2017) Dietary and nutrition interventions for the therapeutic treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 30(3): 247-259.

- Rita Silva (2019) Dietary interventions in fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Annals of Medicine ISSN 51(S1): S2-S14.

- Trabal J (2012) Patterns of food avoidance in chronic fatigue syndrome; is there a case for dietary recommendations. Nutricion Hospitalaria 27(2): 659-662.

- Slim, Calandre, Rico Villademoros (2015) An insight into the gastrointestinal component of fibromyalgia: clinical manifestations and potential underlying mechanisms. Rheumatology international 35(3): 433-444.

- Goedendorp MM (2009) The lifestyle of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and the effect on fatigue and functional impairments. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 22(3): 226-231.

- Woolley J, Allen R, Wessely S (2004) Alcohol use in chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 56(2): 203-206.

- Ruiz Cabello (2017) Association of Dietary Habits with Psychosocial Outcomes in Women with Fibromyalgia: The al Ándalus Project. J Acad Nutr Diet 117(3): 422-432.

- Brown (2014) Chronic fatigue syndrome: A personalized integrative medicine approach. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 20(1): 29-40.

- Brown (2014) Chronic fatigue syndrome: A personalized integrative medicine approach. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 20(1): 29-40.

- NHS (2019a) Fibromyalgia.

- Häuser W, Thieme K, Turk DC (2010) Guidelines on the management of fibromyalgia syndrome - A systematic review. European Journal of Pain 14(1): 5-10.

- American Pain Society (2005) Guideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome pain in adults and children.

- Taylor (2004) Quality of life and symptom severity for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: Findings from a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 58(1): 35-43.

- Taylor (2004) Quality of life and symptom severity for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: Findings from a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 58(1): 35-43.

- (2015) Fibromyalgia and nutrition: what news?. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 33(1 Suppl 88): S117-S125.

- Lowry (2020) Dietary Interventions in the Management of Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Best-Evidence Synthesis. Nutrients 12(9): 2664-2823.

- Ocké (2013) Evaluation of methodologies for assessing the overall diet: dietary quality scores and dietary pattern analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 72(2): 191-199.

- Ocké (2013) Evaluation of methodologies for assessing the overall diet: dietary quality scores and dietary pattern analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 72(2): 191-199.

- Köroğlu, Adigüzel (2020) The role of nutrition in patients with fibromyalgia: Is there an impact on disease parameters?. Gulhane Medical Journal 62(3): 186-192.

- Tomaino (2020) Fibromyalgia and Nutrition: An Updated Review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 40(7): 665-678.

- Mengshoel (1995) Multidisciplinary approach to fibromyalgia A pilot study. Clinical Rheumatology 14(2): 165-170.

- Haß, Herpich, Norman (2019) Anti Inflammatory Diets and Fatigue. Nutrients 11(10): 2315.

- Häuser (2010) Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Research and Therapy 12(3): R79.

- Bidonde J Soo Y Kim, Suelen M Góes, Catherine Boden, Heather Ja Foulds, et al. (2017) Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

- Sosa-Reina (2017) Effectiveness of Therapeutic Exercise in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials p. 14.

- Anderson, Winkler (2006) Benefits of long-term fibromyalgia syndrome treatment with a multidisciplinary program. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 14(4): 11-25.

- Bailey, Leslie Starr, Monica Alderson, Julie Moreland (1999) A comparative evaluation of a fibromyalgia rehabilitation program. Arthritis Care and Research 12(5): 336-340.

- Lemstra, Olszynski (2005) The Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Clinical Journal of Pain 21(2): 166-174.

- Sandler, Lloyd, Barry (2016) Fatigue Exacerbation by Interval or Continuous Exercise in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 48(10): 1875-1885.

- NICE (2020) Guideline Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management. Draft for consultation, November 2020.

- Lauche (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction for the fibromyalgia syndrome, Journal of Psychosomatic Research. Elsevier Inc 75(6): 500-510.

- Haugmark (2019) Mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions for patients with fibromyalgia A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLOS ONE GL Santana (Eds.), 14(9): e0221897.

- Lakhan, Schofield (2013) Mindfulness Based Therapies in the Treatment of Somatization Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis, PLoS ONE. Edited by M. Sampson. 8(8): e71834.

- Meeus (2015) The effect of relaxation therapy on autonomic functioning, symptoms and daily functioning, in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation 29(3): 221-233.

- Poole, Siegel (2017) Effectiveness of Occupational Therapy Interventions for Adults with Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review. The American journal of occupational therapy 71(1): 7101180040p1-7101180040p10.

- Bernardy, P Klose, P Welsch, W Häuser (2018) Efficacy, acceptability, and safety of cognitive behavioral therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Pain 22(2): 242-260.

- Malouff (2008) Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: A meta-analysis, Clinical Psychology Review 28(5): 736-745.

- Castell, Kazantzis, Moss Morris (2011) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Graded Exercise for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome A Meta Analysis, Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 18(4): 311-324.

- Young C (2019) Supporting Engagement, Adherence, and Behavior Change in Online Dietary Interventions, Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 51(6): 719-739.

- Johnston, Staines, Marshall Gradisnik (2016) Epidemiological characteristics of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in Australian patients, Clinical Epidemiology 8: 97-107.

- Arroll, Elizabeth A Attree 1, Clare L Marshall 1, Christine P Dancey (2014) Pilot study investigating the utility of a specialized online symptom management program for individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome as compared to an online meditation program. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 7: 213-221.

- Browne S (2019) Effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving dietary behaviors among people at higher risk of or with chronic non-communicable diseases: an overview of systematic reviews. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 73(1): 9-23.

- Hou SI, Charlery, SAR, Roberson K (2014) Systematic literature review of Internet interventions across health behaviors. Health Psychology & Behavioural Medicine p. 2.

- University of Worcester (2018) Research Ethics Policy.

- Hamnes (2012) Effects of a one-week multidisciplinary inpatient self-management programme for patients with fibromyalgia: A randomised controlled trial, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders pp. 13-189.

- Lacour (2002) An interdisciplinary therapeutic approach for dealing with patients attributing chronic fatigue and functional memory disorders to environmental poisoning -- a pilot study 204(5-6): 339-346.

- Denscombe (2017) The Good Research Guide; For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. 6th edn, Open University Press, London, UK.

- Spaeth (2009) Epidemiology, costs, and the economic burden of fibromyalgia, Arthritis Research and Therapy. Bio Med Central 11(3): 117.

- Hunter, Paxman, James (2017) Counting the Cost Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. London, UK.

- Hickie (2009) Are chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome valid clinical entities across countries and healthcare settings, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 43(1): 25-35.

- Bennett, Ronald Friend, Kim D Jones, Rachel Ward, Bobby K Han, Rebecca L Ross, et al. (2009) The revised fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQR): Validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Research and Therapy 11(4): 120.

- Physiopedia (2020) Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR).

- Williams DA, Arnold, LM (2011) Measures of fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale, and Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire (MASQ), Arthritis Care and Research 63(Suppl 11): 86-97.

- NHS (2019b) Get help with anxiety. fear or panic.

- Julian (2011) Measures of anxiety: State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care and Research 63(Suppl 11): S467-S472.

- Smarr KL, Keefer AL (2011) Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care and Research 63(Suppl 11): S454-S466.

- Pallant (2016) SPSS Survival Guide. 6th McGraw Hill Education, London, UK.

- Ocké (2013) Evaluation of methodologies for assessing the overall diet: dietary quality scores and dietary pattern analysis, Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 72(2): 191-199.

- Cleghorn (2016) Can a dietary quality score derived from a short-form FFQ assess dietary quality in UK adult population surveys?, Public Health Nutrition 19(16): 2915-2923.

- Medical Research Council (2020) Diet Checklists. DAPA Measurement Toolkit.

- Béliard S, Mathieu Coudert, René Valéro d, Laurie Charbonnier a, Emilie Duchêne, et al. (2012) Validation of a short food frequency questionnaire to evaluate nutritional lifestyles in hypercholesterolemic patients. Annales d Endocrinologie 73(6): pp. 523-529.

- Khalesi S (2017) Validation of a short food frequency questionnaire in Australian adults. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 68(3): 349-357.

- Bingham SA, C Gill, A Welch, A Cassidy, S A Runswick, et al. (1997) Validation of Dietary Assessment Methods in the UK Arm of EPIC Using Weighed Records, and 24-hour Urinary Nitrogen and Potassium and Serum Vitamin C and Carotenoids as Biomarkers. International Journal of Epidemiology © International Epidemiological Association pp. S137-151.

- Bingham SA, AA Welch, A McTaggart, AA Mulligan, SA Runswick, et al. (2021) Nutritional methods in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer in Norfolk. Public Health Nutrition 4(3): 847-858.

- Kant (2004) Dietary patterns and health outcomes, Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 104(4): 615-635.

- Bowling (2009) Questionnaires, in Press, OU. Ed. Research Methods in Health, investigating health and health services. 3rd Edn, Maidenhead.

- Bennett, Ronald Friend, Kim D Jones, Rachel Ward, Bobby K Han R, et al. (2009) The revised fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQR): Validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Research and Therapy 11(4): 120.

- Riffenburgh (2006) Summary Statistics, in Statistics in Medicine. 2nd Elsevier Inc, Burlington, USA.

- Field (2018) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 5th Los Angeles: SAGE PublicationsSage CA, Los Angeles, USA.

- Cohen, J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2nd Hillsdale, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, NJ, USA.

- Arroll, Howard (2012) A preliminary prospective study of nutritional, psychological and combined therapies for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in a private care setting. BMJ Open 2(6).

- Surendran S, Mithun CB (2018) FRI0647 Estimation of minimum clinically important difference in fibromyalgia for fiqr using bpi as the anchor measure, in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. BMJ 77(suppl 2): 1-845.

- Häuser (2009) Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arthritis Care and Research 61(2): 216-224.

- Gibson and Gibson (1999) A multidimensional treatment plan for chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Nutritional & Environmental Medicine 9(1): 47-54.

- The Chrysalis Effect (2018) About Us.

- Young C (2019) Supporting Engagement, Adherence, and Behavior Change in Online Dietary Interventions. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 51(6): 719-739.

- Rita Silva (2019) Dietary interventions in fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Annals of Medicine ISSN 51(S1): S2-S14.

- Greaves CJ (2011) Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 11(119): 1471-2458.

- Sanada (2015) Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarker expression in patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Arthritis Research & Therapy 17: 272-288.

- NICE (2020) Guideline Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management. Draft for consultation, November 2020.

- Baptista (2013) Assessment of art therapy program for women with fibromyalgia: Randomized, controlled, blinded study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 71(supp 3): 271.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...