Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1381

Research Article(ISSN: 2644-1381)

Ninety-Five British Gulf War Health Professionals’ Met and Unmet Expectations of Re-Entry to Civilian Life Following Military Deployment Volume 1 - Issue 5

Deidre Wild*

- Senior Research Fellow (Hon), Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, Coventry, England

Received: September 25, 2019; Published: October 02, 2019

*Corresponding author: Deidre Wild, Senior Research Fellow (Hon), Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, Coventry, England

DOI: 10.32474/CTBB.2018.01.000122

Abstract

Ninety-five British ex-Army Reserve and Voluntary Services (predominantly Territorial Army) health professional veterans (HPVs) of the 1991 Gulf War (GW) gave their reactions towards notice of embarkation for the return home and thence to the subsequent events of demobilization, reunion, and their return to civilian work. Collectively these events mark the transition from the role of soldier back to that of civilian. Postal survey data were collected six months after participants had returned home from the Gulf. The findings show that although the war was short and with few Coalition casualties, a sizeable number of the HPVs were dissatisfied with their embarkation,demobilisation and homecoming as reality did not meet their pre-event expectations. The findings are discussed in relation to the related knowledgebase from other wars preceding and succeeding the GW.

Keywords: Gulf War; Non-regular services health professionals; Homecoming; Met and unmet expectations

Introduction

Several studies of newly demobilized veterans following

participation in warfare have described homecoming and

adjustment to normal life as running contrary to their anticipatory

expectations [1-3]. Based upon a major study of World War 11

personnel, family stability was disrupted following the return home,

as relationships were re-established [4,5] but unlike separation,

the early event of reunion was marked positively by the elation

and joy of both spouses [4]. However, a study contemporary with

the GW found that the very act of trying to achieve normal living

was seen to be a stressor for the veteran and it was suggested that

family members could be prone to secondary stress [6]. In a sample

of 64 US Vietnam veterans [3], early post war family friction was

observed from a mismatch between the veteran’s own fantasy of

reunion and the reality of re-entry into a family that had learned

to cope with life in his or her absence. Powerful emotional conflict

between family members arose as they learned to re-include the

veteran, who could have changed physically or emotionally as a

result of participation in warfare [3].

The above pre-GW wars had deployment separations that were

considerably longer than that of the GW and the return home was

often staged due to the distance involved between the war zone and

home. In doing so, this permitted time for adjustment. In contrast,

due to direct air transportation to the UK, GW veterans had little

time between leaving the Gulf and returning to civilian life. Even

when available, there was little uptake of military-sponsored

advisory programmes designed to help veterans unwind and

offload (debrief) [7]. Yet, having this time is regarded as particularly

important to veterans as they prepare mentally to leave a war-zone

behind them and focus upon reintegration back into their civilian

world [8,9].

Although attention is drawn to the paucity of research

concerning reunion and reintegration, what has been recognised

is that homecoming rituals are important markers of adaptive

change from being in wartime military service to the resumption

of normal civilian or peace-time military life [10]. Rituals might

include family or work celebrations. These can facilitate closure

for war-time experiences and by heightening emotions, enable

the expression of feelings. The authors suggest that veterans can

become isolated if their pre-event fantasy of homecoming falls

short in its reality, or if they fail to recognize that within the family, changes have taken place during their absence. Furthermore, they

recommend that research concerned with reunion should include:

a matching of the expectation of homecoming with the reality; the

subsequent interactions of family members with the veteran, and

an identification of how change has taken place from before to

after the war [9]. Most of these suggestions were anticipated for

inclusion in the present study’s inquiry.

Methodology

Design

A longitudinal mixed method design was employed using postal questionnaires to collect data over three time points, each six months apart. This article focusses upon data from the first collection commenced 6 months after the end of the GW (September 1991). This recorded qualitative and quantitative data concerning pre-deployment, deployment and reunion and re-entry. Longitudinal data comparing and examining change over the total study from six months before the war to 18 months post war will be presented in a future article.

Materials

A draft pool of dichotomous and scale items was generated and the content and format of the survey’s first questionnaire were suggested and amended with input from 7 HPVs, who in addition to participating as a part of the study’s sample, also acted as participants in the scoping Pilot study. The final questionnaire included both open and closed questions to allow for explanation and elaboration that could further the exploratory and descriptive approach. In this way, the mixed method adopted, produced both quantitative and qualitative data which enhanced understanding more so than using one or other of these on its own [11].

Participants and Recruitment Procedure

The recruitment strategy is given in Figure 1. As shown, the first of three stages of the recruitment of the study’s participants was opportunistic. One HPV Reservist nurse (a work colleague known to the author) held a personal address list of 74HPVs (including herself) who had returned together by air to the UK in March 1991 following the end of the GW. As it was considered to be unethical for the author to have direct access to the veterans’ addresses without their permission, the colleague agreed to act as an intermediary by forwarding a letter from the author with: details of the study to each potential participant; a pre-paid postal return form for their contact details, and a consent form for completion. In the event, 57 (47 ex regular Reservists and 10 Territorial Army personnel) of the 74 HPVs gave their agreement to participate in the study, providing a return rate of 77%.

In the second recruitment stage, a purposive increase of the TA

group was sought to match that of the Stage 1 recruited Reservists

and in similar health professional roles. This was achieved by

asking the 10 consenting VS TA participants from Stage 1, to act as

‘intermediaries’ in making a ‘snowball’ access to similar (in military

group and role) others within their own or other TA units. To

facilitate this, each of them was supplied with 5 introductory letters

(n=50) with pre-paid return contact slips with direct return to the

authors. In this way a further 33 TA HPVs agreed to participate in

the study raising the total for the TA to 43. Although there was no

way of knowing if all of the 50 letters provided had been issued, the

percentage estimate for those giving consent (post receipt of study

information and return of consent forms) was at a satisfactory level

(66%).

Finally, in a third recruitment stage, a GW veteran Welfare

Officer in the Order of St John of Jerusalem, who having heard of the

study, made direct contact with the author to seek inclusion for the

10 Welfare Officers who had been volunteers in the GW. Following

the issue of 10 introductory letters with return, contact and consent slips to the organisation’s initial contact for distribution, 5 (50%) of

these veterans agreed to become participants.

The total of 134 contact letters issued across the three recruitment stages resulted in 95 consenting HPVs. An estimated minimum overall response rate of 71% was obtained from the three stages of recruitment. At the time of recruitment to the study, the numbers of TA and Reserve personnel deployed to the GW had not been reported in the public domain. However, figures given some years after the GW suggest that the 95 HPVs in the participant sample represents some 9% of the total population of British Reserve and TA (or other voluntary military organization) deployed personnel [12].

Nature of the Present Inquiry

This article explores:

• The HPVs’ perceptions of embarkation and the identification of those most likely to be negative.

• The HPVs’ perceptions of demobilisation.

• The HPVs’ met and unmet expectations of homecoming and who was the most likely to have experienced the latter.

The questionnaire’s variables of interest

The following three variables in the first questionnaire provided the data for this article:

• Open question: What were your reactions to embarkation? The analysis of its qualitative responses formed a new variable with the values of: 1. Positive reactions; 2. Mixed reactions; 3. Negative reactions.

• Open question: What were your expectations for your homecoming?

• Closed question: Did the event of your homecoming meet with your expectations?

1. Yes completely; 2. Some disappointment; 3. Very disappointed; 4. Unsure

Please justify your response below.

• Personal, professional and military characteristics (Table 1) plus age and length of time in the Gulf (and in the military) were coded as the independent variables for the logistic regression model used for questions 1 and 3.

Ethical considerations

Although the study’s ethical considerations preceded the requirements of the formal ethical system that accompanies the conduct of today’s research, the general principles of the researcher doing no harm; securing informed consent; accepting the participant’s autonomy over compliance, and respecting the participant’s rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality have been upheld to date [13]. Authoritative military and academic advice was taken throughout the study to avoid potentially sensitive issues. All information forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data were held securely and in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in 1998.

Analysis

Quantitative dichotomous data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22. Logistic regression with a forward stepwise Wald was employed to test the significance of the ‘odds’ of the dependent variable’s value of interest in relation to those of the HPVs’ personal, professional and/or military characteristics acting as independent variables. Qualitative data in the form of the HPVs’ comments were subjected to thematic content analysis and were examined first by two researchers working independently to identify key words or phrases. These were then categorised as labels to capture as closely as possible the meaning of the HPVs’ original words or phrases [14]. Themes and sub-themes were identified [15]. The two researchers then made cross comparisons to reach consensus. In some instances, the qualitative data were transformed into new variables that permitted the use of descriptive statistics.

Results

Characteristics of the Participant Sample

Personal, professional and military characteristics are given

in Table 1. The HPVs’ ages ranged from 23 to 53 years (mean=37;

SD=8.59; median=35). When the figures for the civilian occupations

of the 95 HPVs were cross tabulated with their qualifications, 67

of the 68 held nursing qualifications (1 missing) and of these, 49

(73%) worked as Registered General Nurses; 4 (6%) as Registered

Mental Nurses, and the remaining 14 (21%) were State Enrolled

Nurses.

All of the health professionals (nurses, doctors, physiotherapists,

etc.) worked in the same professions in the GW as in their pre-war

civilian work but in the war zone, nurses were often assigned to

different and unfamiliar roles. Only combat medical technicians

(akin to civilian ambulance paramedics) worked in non-health

civilian roles prior to the GW. Of the 95 HPVs, 27 (28%) had

previous warfare experience and of these, 17 (18%) were ex

Regular Reservists and 10 (10%) were in the TA. The remaining 68

(72%) had no experience of warfare.

The time spent in the Gulf (in weeks) for most HPVs was

between 8 and 12 weeks. When the HPVs’ length of time in the Gulf

was compared with their deployment military categories using a

Mann-Whitney U test, Reservists were found to have spent less time in deployment (mean rank=37.16) than those in the TA (mean

rank = 58.61), a significant difference (U=618.500, Z= -2.414,

p<0.01). Eighty-four HPVs recorded their length of military service

in a range of 1-36 years (mean=9.02, SD=7.52) with a median of

6 years. Of the 11 who failed to respond to this question, 6 were

VS TA volunteers who could have regarded the question as seeking

sensitive information and the remaining 5 were civilian Welfare

Officers, who may have considered the wording of this question as

being specific only to those in the military.

Length of Time to Embarkation

Of the 95 HPVs, 12 (13%) had less than one day’s notice of embarkation by air to the UK, 62 (65%) HPVs had 2-7 days, and the remaining 21 (22%) had more than 7 days but none stayed in the Gulf more than 2 weeks post notification.

Content Analysis for the HPVs’ Reactions to Embarkation

Ninety-four HPVs provided written comments and from these their positive (n=48:50%), mixed (n=27:28%) and negative reactions to embarkation (n=20:21%) were identified. The dominant theme within the positive reactions was one of extreme happiness, usually expressed in single words such as ‘elated’, or as a profound sense of relief at leaving an unreal world behind and getting back to the reality of home:

Thank Christ I’m going home, back to the real world and real people.’ (Male Reservist called up, nurse other rank)

A few felt pride in what they had achieved:

Elated - Pride in having done my best and having passed on my skills to others.’ (Male TA volunteer, nurse officer)

mixed comments, the overall impression was one of uncertainty about the timing of their departure from the Gulf. For some Reservists there was the expectation that as latecomers to deployment in the Gulf, they would be the last to leave and this was kept at the fore of their minds, perhaps to minimise disappointment:

Didn’t really believe we would be going as quickly being

Reservists. We thought last in we would be last out. Always doubt in

mind though that it could be cancelled. Didn’t really celebrate until

on the plane.’(Male Reservist called up, CMT other rank)

‘I can only describe them [feelings] as controlled excitement,

because we had been told so many times that we would be leaving

soon, that I wasn’t prepared to believe it until I was on the plane and

airborne.’ (Female Reservist called up, nurse other rank)

For others there was happiness coupled with disappointment at the War ending without the achievement of their perceived goal, i.e. the destruction of the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq:

Happy, but sorry it was a job left undone.’ (Male Reservist volunteer, nurse officer)

Other HPVs could not give a reason for their mixed feelings but simply sensed they were just not ready to go home:

‘Happy but it was too soon. I just didn’t feel ready to go home’ Male TA volunteer, CMT other rank)

Of the 20 (21%) negative comments, some reflected the HPVs’ dread of resuming their home life, and also the sense of loss at the prospect of separation from the colleagues with whom they had lived and shared their war-time experiences:

‘I wasn’t looking forward to coming home as I’d made lots of new friends who I knew I would miss. I was apprehensive about how I would cope living on my own again having lived as one of 800 personnel for 3 months.’ (Female TA volunteer, nurse officer)

Thoughts of the return home were compounded by the prospect of a return to problematic relationships at home and in a few cases this was complicated by the romantic liaisons formed during deployment.

‘Depressed. I felt I had still a valuable job to do - casualties were still coming through the hospital. I didn’t believe the cease-fire would hold and that the War was over. Additionally, I was enjoying myself there, despite the conditions. (Male, other rank Reservist who had formed an extra-marital relationship and had a difficult relationship with his spouse at home, to whom he did not want to return.)

For some Reservists the prospect of embarkation reopened resentments arising from their widely-held belief during deployment of being marginalised in favour of Regulars and as in the following comment, also by some in the TA:

‘Strange really - a bit let down - I was annoyed at being treated again as just a Reservist. I wanted to come home as a part of the unit (22 Field Hospital) because I had worked as hard as any of them [TA] and felt part of them - not just a Reservist who was no longer needed.’ (Female Reservist called up, nurse officer)

Quantitative Analysis for Reactions to Embarkation

To facilitate logistic regression, the above qualitative data from

the 94 HPVs were transformed into a new variable titled ‘reactions

to embarkation’ with the values of ‘negative reactions’ = 1 (provided

by 20:21% of HPVs) and ‘positive and mixed reactions combined’ =

0 (provided by 74:79% of HPVs).

When this variable was entered as a Dependent Variable (DV)

with the other sample characteristics as Independent Variables (see

Table 1 for values) using logistic regression, the interaction term

‘age/sex’ was found to be significant (B=0.053, r=0.213, Exp [b]=1.

054, Sig. p<0.01). In this, older females had a significantly greater

likelihood of having negative reactions towards embarkation after

the war’s end than younger females or males of any age.

Content Analysis for Pre-Embarkation Expectations of Homecoming

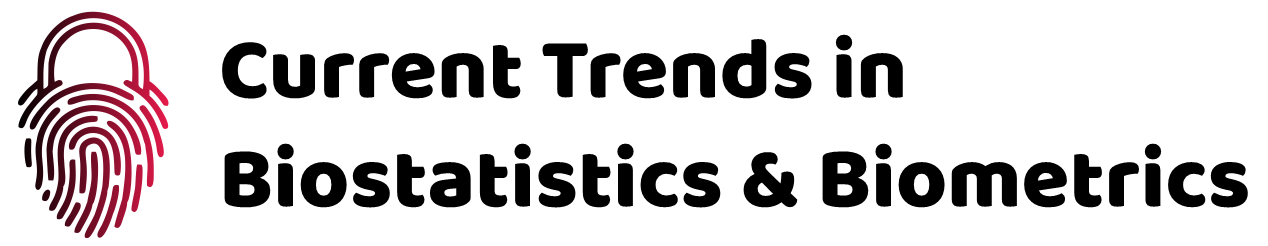

The 95 HPVs were asked to comment if they had expectations of homecoming prior to embarkation to the UK, and 78 (82%) HPVs said they had expectations, 10 (11%) had no expectations, and 7 (7%) were unsure. When asked to describe their expectations, 73 (94%) of the 78 HPVs with expectations complied and content analysis of their comments produced 117word labels. As shown in Table 2, when the word labels were further analysed, they formed two themes:

In the event, a higher percentage of the HPVs had expectations of others (63%) rather than of themselves (37%). The most frequently expressed sub-theme ‘to get back to a normal life’ was described by (26%) of the HPVs mainly in terms of their resumption of the activities and freedoms of normal life at home that had been curtailed by deployment:

Good food, drink, bath, sex, normality!’ (Male TA volunteer, other rank, nurse)

There also was recognition that there was a need for time to adjust to the transition from soldier to civilian in post war life. In some comments, adjustment was anticipated as a solitary process that could have excluded those in their close social network and become a source of disharmony:

‘To be left alone to come to terms with my own feeling/emotions.’ (Male Reservist volunteer, other rank, nurse)

Of the expectations of others, informally organized celebratory reunions by family and friends were more frequently raised than formal celebrations organized by government or the military. Nevertheless, symbolic public and military recognition as experienced in the troops’ homecoming from the Falkland War in 1982 was high in the minds of some HPVs:

‘A Falklands type of hype.’ (Male Reservist called-up, other rank,

CMT)

‘The usual military razzmatazz when troops return home from

conflict and the usual welcome home from the British public.’ (Female

TA volunteer, officer, nurse)

Only 10% of the HPVs held the expectation of a quiet familyonly type of reunion.

Content Analysis of the HPVs’ Experience of Demobilisation

For some HPVs, the reality of the process of demobilisation caused a sense of disappointment and anti-climax even before their arrival at their UK homes. The absence of close family to welcome the HPVs back on arrival in the UK was raised, and often this was blamed upon military organisational deficits:

‘My TA unit did not offer to bring my wife to greet me. My C.O. did not arrive to greet us, nor did he provide transport home. This was done by a fellow officer out of his own pocket.’ (Male TA volunteer, junior officer nurse)

The HPVs who held expectations of being recognised by society at large for their participation in the war at the point of their return were also due to be disappointed:

‘It would have been nice to have had some recognition by the

Government and Press on arrival.’ (Male Reservist called up, other

rank nurse)

The people that came home first had big celebrations but when

we got back there was no-one there to greet us except for our C.O.

There was no thanks for volunteering and no time to say goodbye to

friends made.’ (Female TA volunteer, senior officer nurse)

The lack of transportation to home was a major unanticipated problem that arose once the demobilisation process had been rushed through:

‘Very rapid demobilisation. Felt MOD wanted us away as soon as possible. Cold and formal process. All were tired as we had waited several days to board an aircraft and had been cancelled and changed 3-4 times. No transport home and no time to absorb details.’ (Female TA volunteer, nurse officer)

Following the demobilisation process, although some HPVs had their expectations met in terms of a happy reunion with families at demobilisation sites, for others, unanticipated family tensions quickly surfaced:

‘My husband yelled at the kids and me the minute I got off the plane. My teenage daughter was surly (not her usual disposition) and my little boy just sat and cried.’ (Female Reservist volunteer, senior officer nurse).

HPVs’ Met and Unmet Expectations of Reunion

The few HPVs who held low key expectations of reunion with family, largely had these met in reality:

‘A welcome home. The hero-type of reception was not expected nor given. I expected a quiet family welcome and that is what I got.’ (Male TA volunteer, officer, nurse)

In contrast, content analysis created 79 word labels in 4

thematic groups of unmet expectations. These groups and their

frequencies are given below as bullet points in Table 3, where they

are contrasted with the fantasy of the HPVs’ earlier expectations

of homecoming (Table 2). As can be seen, the three sub-groups of

HPVs who held expectations of others perceived these as not being

met in the reality of homecoming.

Within a short time of returning home, disappointment

and anti-climax was experienced due to the unexpected lack of

recognition and interest of others in their war service.

‘I thought a lot more people would want to know what happened

- not true. (Male TA volunteer, other rank CMT)

‘I was home. Apart from family and close friends being glad, no

one was interested. It was a big anti-climax.’ (Female Reservist, junior

officer nurse)

The reality of homecoming for many HPVs was that the media had quickly ceased to regard the GW as news once hostilities were over. Thus, by the time of their return the public had lost interest in the GW and its participants.

The War had ended a few weeks beforehand and interest amongst my friends had already waned. Life was back to normal by the time we got home.’ (Male Reservist called up, senior officer doctor)

Reservists who held post–war expectations of public recognition perceived further marginalization (in addition to the delay at embarkation) with their exclusion from the formal National celebration of the war’s end held in London some months after the return home:

‘Army haven’t spoken to me since I landed. No invite to any Gulf Parade to watch or join in. (Male Reservist volunteer, other rank, medical laboratory technician)

A few HPVs raised the issue of post war adjustment to the change that they perceived they or others had undergone following the war’s end. However, very few HPVs articulated how they had changed or what adjustment problems they were having and only a small number of HPVs raised the stress undergone by those in their close family due to the deployment separation. The following comments express the confusion felt by some HPVs in knowing that they were experiencing change but not with understanding as to what the change was:

‘I felt I was to fit into the life I had left behind with no choice,

even though I felt different.’ (Female Reservist called up, junior officer

nurse)

‘People were funny. I thought they had changed not me, i.e. they

were moody. I don’t know, it is hard to explain.’(Female Reservist

volunteer, senior other rank nurse

‘Apprehensive re: meeting family. Thought they would understand

that one needed time to readjust.’ (Female TA volunteer, junior officer

nurse)

‘I expected domestic/personal relationships to be strained (like

this before the war). I was unsure of my future - whether I wanted the business I had set up and also whether I wanted to remain

married.’(Male Reservist [Other characteristics removed to protect

identity])

Of work relationships, negative comments were related to both managers and work colleagues and reflect a lack of tolerance and understanding from some of them towards the HPVs. Managers seemed to hold an expectation that the HPVs were likely to be a source of instability in the workforce if called up or expected to volunteer ahead:

‘I feel that my manager was very intolerant of me when I came

back and this attitude has stuck. Think he thought I’d go off again’

(Female TA volunteer, senior officer nurse)

‘Work colleagues were unable to understand that this was

what I trained for in the TA. They found it hard to accept that I was

going when I didn’t have to. I was made to feel I was leaving them

in the lurch by their having to take over my job.’ (Female TA officer,

volunteer nurse)

Some work-colleagues tended to exhibit ill placed humour, possibly masking jealousy:

‘Great tan - nice holiday?’ (Female Reservist officer, nurse)

Quantitative Analysis: Opinion of Homecoming

The qualitative data from the 91 HPVs giving their opinion of homecoming (four missing) facilitated the creation of a new dependent variable: ‘opinion of homecoming’ with the logistic regression values of: ‘Satisfied with the event’ (45:47%) = 0. and ‘Part/ wholly disappointed’ (46:53%) = 1. Using the sample characteristics as the IVs, the outcome of this analysis demonstrates that ‘length of military service’ was the best predictor of the HPVs’ opinion of homecoming with those with ‘a shorter length of military service’ having a significantly increased likelihood of having an opinion of homecoming that was ‘part or wholly one of disappointment’ (B= -0.116, R=0.154, Exp(β=0891, p<0.01).

Discussion

The length of time between notification for embarkation in the Gulf and transportation back to the UK was most commonly less than a week and reflects other authors’ accounts describe as a period of heightened anticipatory and conflicting emotions [16,17] as the veterans focused upon how they would be received at home by family, work colleagues, friends, the military establishment and society in general. Within this time, similar to US non Regular troops [7], some HPVs reported their uncertainty as: not knowing precisely when embarkation would take place; the lack of time for debrief with others who had shared the experience, and the speed of an impersonal discharge following arrival back in the UK. Reservists, in particular commented that they had expected to be marginalized with regard to an early return with preference being given to those in the TA. Although not confined exclusively to the population of Reservists, these expectations became reality with several delays and re-schedules before finally leaving the Gulf. Some Reservists who worked in a TA general hospital felt angry that they were excluded from the media call held exclusively for TA personnel on arrival in the UK.

In general, the HPVs’ speedy, chaotic and impersonal military

demobilization process undermined their earlier sense of joy at

the prospect of homecoming and allowed no time for adjustment

from being a soldier to becoming a civilian. As such, this scenario

runs contrary to several authors’ research-based recommendations

to minimize the potential for delayed or chronic mental health

problems that have arisen from wars before [18-21] and after the

GW [22-25].

Being an older female was identified as the best predictor of

negative reactions towards embarkation following the War’s end

but justification for this was not transparent from the related

qualitative data. Thus, a two-fold tentative explanation can be

offered. First, older females could have been less enthusiastic

than younger females and males of any age in contemplating a

homecoming which may well have required the resumption of

tying responsibilities such as the care of aged parents. Similarly,

as reported by nurses returning from Vietnam [19,20], the

anticipation of a return to their civilian nursing roles could have

been perceived as being less stimulating than their war-time roles

with its advanced clinical decision-making. Although some caution

is recommended in ascribing particular behaviour to numeric age

[26], other authors suggest a tendency towards increased prosocial

behaviour as life gains in mid-life [27] and older females may

have felt that they were still needed to care for refugees and clean

up the environment in Saudi Arabia.

The GW had the popular support of US and UK societies [28]

but contrary to wars such as Vietnam [29], the memorable public

‘welcome home’ given to the Falklands War’s returning troops

[30] unrealistically fueled the expectations of many returning

HPVs. Several explanations can be postulated for this particular

lack of reality and disappointment. Initially, the GW was regarded

as unique in its high-profile media coverage in the run-up to and

during the war [28], holding centre-stage due to the public’s belief

in its potential for mass casualties from a biochemical warfare

scenario. However, in reality, he short offensive campaign with low

casualties resulted in the media’s and public’s interest in the war

quickly waning.

HPVs with a shorter military service were more disappointed

with the homecoming event than those with a longer military

service. This most likely arose because those with less military

experience could have held more naïve expectations of celebrating

‘the heroic warrior’s return’ [31] but once home, they found that

society’s interest had moved on to new matters. Unlike those in the

TA with their military part-time units, for Reservists, the military

friends made under the testing circumstances of modern warfare

were scattered often without time to say goodbye. A further source

of distress for some HPVs was their arrival back in the UK with no

organised plan or financial assistance to get them home.

It has been suggested that in reality, the family reunion

event is doomed to fail, no less because it does not take into

account the changes in the family that has learned to cope with

separation [3]. This proved to be the case for many of the HPVs

who expressed disappointment and anti-climax with homecoming

having misjudged or overlooked their significant others’ war related experiences arising from separation. For some HPVs the

return home resurrected unresolved problems arising during predeployment

and left unaddressed by the time of departure to the

Gulf [17].

The return to civilian work offered little relief or support. In

the UK, many NHS general hospitals were placed on standby for

GW casualties [32] and often their staff were the HPVs’ pre-war

civilian work colleagues. These staff could have had their own

sense of post-war anti-climax from the almost total lack of use

of the extensively prepared for facilities for GW casualties. The

message perceived by HPVs from them was that the GW with its low

casualties was not a ‘real’ war but an extended holiday in the sun

whilst they (NHS staff) had to undertake the additional workload

that the HPVs’ absence had created. Such attitudes were neither

expected nor anticipated by the HPVs, particularly as in other parts

of this study, employers and work colleagues before departure

were described as being the most supportive relationships in their

social networks. Furthermore, misguidedly some NHS staff’s postwar

attitudes were that giving time and support for the HPVs’ postwar

adjustment was not necessary. Some authors suggest that warrelated

problems that cannot be readily seen could be perceived

as unlikely to be real. Several authors report that this was the

Government’s belief too at that time [33,34].

Recently, published research from the present study shows

that military advice, provided at the time of embarkation and

designed to alert the HPVs to the potential for post-war adjustment

problems, was poorly disseminated and subject to ridicule by

some troops [35]. This is not surprising, as its timing (upon

embarkation) coincided with the HPVs’ elation at the prospect of

going home. Moving forwards in time, in 2011, a large comparative

study was published [25] comprising British Reservists (TA and

ex Regular Reservists) with Regulars from the war in Afghanistan

(2001-2011). In this, Reservists in particular did not seem to have

benefitted from the experiences of GW veterans some 20 years

earlier in terms of preparation for re-entry into civilian life. For,

they were reported as being more likely to feel unsupported by the

military, to report mental illness symptoms more frequently, and

to find the transition from soldier to civilian more difficult than

Regulars following their return home [25]. Finally, in present times,

two studies both concur that post deployment re-entry to civilian

life requires veterans to recognise that they have problems and to

actively initiate the seeking of help [36,37].

Limitations

The participants were neither a representative sample nor was it possible to match HPVs with controls or find a comparative group, thus generalization is not intended. It is possible that the small sample numbers in some categories may have reduced the efficacy of the use of logistic regression. Nevertheless, it is believed that the richness of the combined findings from the qualitative and quantitative evidence has enabled a reliable picture of the experiences of this group of HPVs and the initial re-integration problems that they faced.

Conclusion

The findings support the premise that despite the GW being a short war with few casualties, similar to earlier wars with longer deployments and with numerous casualties, the experience of embarkation, demobilization and reintegration at home and work resulted in many negative outcomes. In the main, these were sometimes neither clearly articulated by veterans nor understood by those close to them. Veterans tended to see fault more so in others than in themselves when reality was the opposite of anticipatory expectations. Now some 28 years since the GW, ongoing research shows that despite civilian health and welfare services having a better understanding of the veteran’s struggle to disentangle reality from fantasy in a war’s aftermath, more still needs to be undertaken. A starting point for recovery could lie in supporting veterans to first understand their own reactions before those of others to the experiences that have led to their perceptions of changes in newly resumed civilian lives. The evidence also suggests that the military should take better care of its troops in facilitating a more positive climate for their exit from deployment service to civilian veteran status.

References

- Blount BW, Curry A, Lubin G I (1992) Family separations. Military Medicine 157(2): 76-80.

- Hobfoll SE, Spielberger C, Breznitz S, Figley C, Folkman S, et al. (1991) War-related stress: Addressing the stress of war and other traumatic events. American Psychologist 46(8): 848-855.

- Borus FB (1973) Re-entry: Adjustment issues facing the Vietnam returnee. Archives of General Psychiatry 28(4): 501-506.

- Hill R (1949) Families under stress: Adjustment to the crises of war separation and reunion. New York: Harper and Bros pp. 443.

- Hill R (1958) Generic Features of Families under stress. Social Case Work 49(2): 139-150.

- Figley CR (1993) Coping with the stressors on the home front. (Psychological research on the Persian Gulf War). Journal of Social Issues49(4): 51-57.

- Deahl MP, Gillham AB, Thomas J, Searle MM, Scrinivasan M (1994) Psychological sequelae following the Gulf War. Factors associated with subsequent morbidity and the effectiveness of psychological debriefing. British Journal of Psychiatry165(1): 60-65.

- Dunning CM (1996) From citizen to soldier: Mobilization of Reservists. In: Ursano RJ, Norwood AE (eds.) Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War. Veterans, families, communities and nations. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc pp. 197-226.

- Yerkes SA, Holloway HC (1996) War and homecomings: the stressors of war and of returning from war. In: Ursano RJ, Norwood AE (eds) Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War. Veterans, families, communities and nations. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc pp. 25-42.

- Mateczun JM, Holmes E (1996) Return, readjustment and reintegration: The three R’s of family reunion. In: Ursano RJ, Norwood AE (eds) Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War. Veterans, families, communities and nations. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc pp. 369-392.

- Creswell W (2003) 2nd (edn). Research design: Qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Cummins, R (1989) Locus of control and social support Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Lee HA, Gabriel R, Bolton PJ, Bale AJ, Jackson M (2002) Health status and clinical diagnoses of 3000 UK Gulf War veterans. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 95(10): 491-497.

- Merrell J, Williams A (1995) Benefice, respect for autonomy and justice: Principles in practice. Nurse Researcher 3(1): 24-32.

- Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury Park and London. Sage pp. 272-273.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101.

- Pincus SH, House R, Christensen J, Adler LE (200I) The emotional cycle of deployment: A military family perspective. Journal of the Army Medical Department 4: 615-623.

- PeeblesKleiger MJ, Kleiger JH (1994) Re-integration stress for Desert Storm families: Wartime deployments and family trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 7(2): 173-194.

- Raphael B. (1986) When Disaster Strikes. A Handbook for Caring Professions. London: Hutchinson pp. 219.

- Paul EA, ONeill JL (1986) American nurses in Vietnam: stressors and aftermaths. American Journal of Nursing 86(5): 526.

- Spoonster Schwartz L (1987) Women and the Vietnam experience. Journal of Nursing Scholarship19(4): 168-173.

- O’Brien LS, Hughes SJ (1991) Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in Falklands veterans five year after the conflict. British Journal of Psychiatry 159: 135-141.

- Haas KL (2003) Stress and mental health support to Australian Defence Health Service personnel on deployment: A pilot study. Australian Defence Force Health Journal 4: 19-22.

- Brereton P, Orme G, Kehoe EJ (2013) The Reintegration of Deployed Reservists: An Australian perspective. Australian Defence Force Journal 1911: 786-797.

- MacManus D, Wesseley S (2013) Veteran’s mental health services in the UK: Are we heading in the right direction. Journal of Mental Health 22(4): 301-305.

- Harvey SB, Hatch SL, Jones M, Hull L, Jones N, et al. (2011) Coming Home: Social Functioning and the Mental Health of UK Reservists on Return from Deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Annals of Epidemiology 21:666-672.

- StuartHamilton I (2000) The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction. London: Jessica Kingsleyp.20-30.

- Timmer E, Bode C, DirrmanKohli F (2003) Expectations of losses and gains in the second half of life. Ageing and Society 23 (1): 3-24.

- Kellner D (1992) The Persian Gulf TV War. Oxford: Westview Press p. 4-7.

- Fleming RH (1985) Post Vietnam syndrome: Neurosis or sociosis? Psychiatry48(2): 122-139.

- Hastings M, Jenkins S (1983) The battle for the Falklands. Book Club Associates, London.

- Mead M (1940) Warfare is only an invention - Not a biological necessity. In: Bramson L, Goethals GW eds. (1968) War. Studies from Psychology, Sociology and Anthropology. 4th (edn.) London and New York: Basic Books Incorporated pp.269-274.

- Yates DW (1991) The NHS prepares for war. Letter. British Medical Journal 302(6769): 130.

- Shephard B (2002) A War of Nerves. Soldiers and Psychiatrists 1914-1994. London: Pimlico pp. 382.

- McManners H (1993) The Scars of War. London: Harper Collins Publishers pp. 398.

- Wild D, Fulton E (2019) British Non-Regular Services Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of Pre-Deployment Military Advice for The Gulf War. Res & Rev Health Care Open Access Journal 3(2):241-249.

- MacManus D, Wesseley S (2013) Veteran’s mental health services in the UK: Are we heading in the right direction. Journal of Mental Health 22(4):301-305.

- Fulton E, Wild D, Hancock J, Fernandez E, Linnane J (2018) Transition from service to civvy street: The needs of armed forces veterans and their families in the UK. Perspectives in Public Health139(1): 49-59.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...