Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4579

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4579)

Behavioral Health Providers and Effectiveness of Electronic Health Record Volume 2 - Issue 2

Idette Harrison1, Sajeesh Kumar2*

- 1MHIIM, Research Scholar, Department of Health Informatics & Information Management, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, USA

- 2PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Health Informatics & Information Management, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, USA

Received: April 04,2018; Published: April 12,2018

Corresponding author: Sajeesh Kumar PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Health Informatics & Information Management, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, 920 Madison Avenue Suite 518, Memphis, Tennessee, USA, Email: skumarl0@uthsc.edu

DOI: 10.32474/OAJBEB.2018.02.000133

Abstract

Research explores how not including or having available patient information from behavioral health providers in electronic health records can reduce the effectiveness or quality of patient care. Individuals with behavioral health issues frequently have additional disorders that can occur and require increased utilization of health services. Other factors such as substance abuse problems, medication noncompliance, and low insight into behavioural health disorders by acute health care providers can create increased violence risk in that community. The violent crime rates of three Tennessee cities (USA) were also examined to determine correlation between behavioral health diagnoses and violent crimes. EHR adoption rates and patient outcomes were also reviewed to determine if better care could occur if behavioral health information about the patient was available in the electronic health record.

Abbreviations: HER: Electronic Health Record; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NSDUH: National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Introduction

In the world of health information technology, there is a focused concern on how to improve patient care and outcomes. One tool established to help achieve this is the federal mandate and implementation of an electronic health record (EHR) for every patient. The federal government issued EHR rules and standards and began incentive payments to acute care healthcare providers in 2011 in order to increase adoption of EHR in healthcare. However, one sector of the health care provider was left out: behavioral health providers. Behavioral health providers are clinical psychologists, clinical social workers, psychiatric hospitals, mental health treatment facilities, and substance abuse treatment facilities. None of these aforementioned categories are eligible to receive incentive payments from the federal government to establish meaningful use of EHRs. Right now, behavioral health providers are classified as either post-acute or long-term care facilities and neither of these provider types are eligible for any incentive payments [1] Only psychiatrists and nurse practitioners who provide mental health and addiction services at community behavioral health organizations are eligible to receive health IT incentive payments. Some behavioral health providers are advocating for the expansion of EHR incentives to behavioral health providers. Many providers believe that mental illness and substance abuse require acute care and heavily affect overall health status. According to Linda Rosenberg, president and CEO of the National Council for Community Behavioral Health Care:

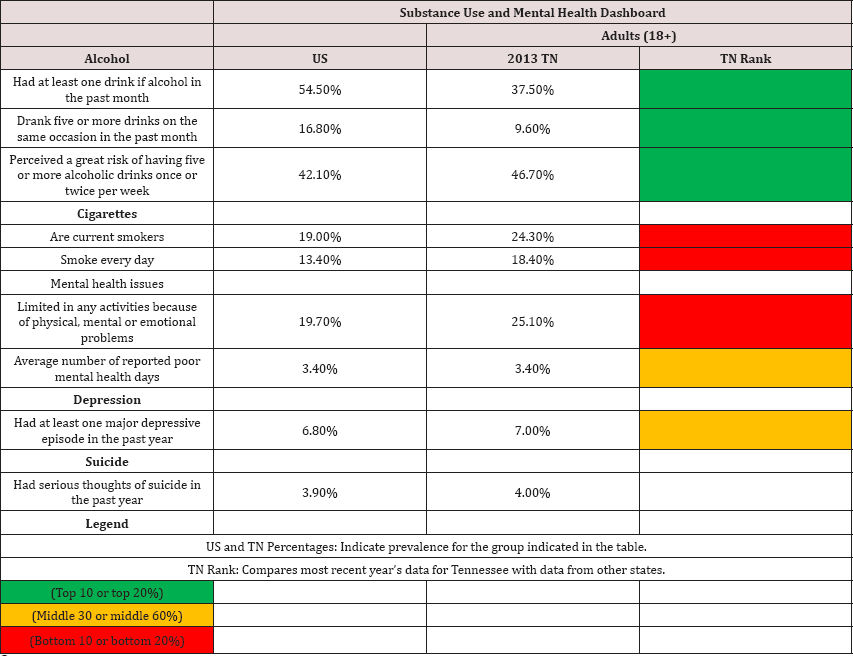

People with mental and substance abuse conditions are in desperate need for more coordinated, integrated health care. Having an interoperable system of electronic health information is critical to achieving greater coordination among addiction, mental health and other health care providers and to helping consumers manage their own health care [2]. In April 2010, state representatives Patrick Kennedy (D-RI) and Tim Murphy (R-PA) introduced the Health Information Technology Extension for Behavioral Health Services Act (HR 5040) to extend incentive payments included in the HITECH Act to mental and behavioral health providers. In March 2011, it was renamed the Behavioral Health Information Technology Act of 2011 (S 539), and sponsored by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI). Sadly both measures failed to pass the House of Representatives Vote and died in Congress after being referred to the Subcommittee on Health. Nationally, mental health and substance abuse disorders are on the rise. Below is a comparison from the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services at how Tennessee ranks against the rest of the 49 states Tennessee [3] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sources:

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data.

2. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) 2012-2013, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey data.

4. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey data.

5. Health Indicators Warehouse. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey data.

Method

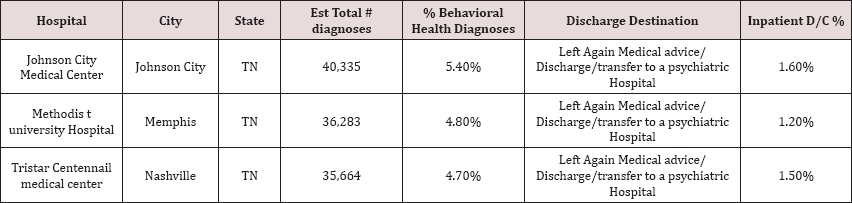

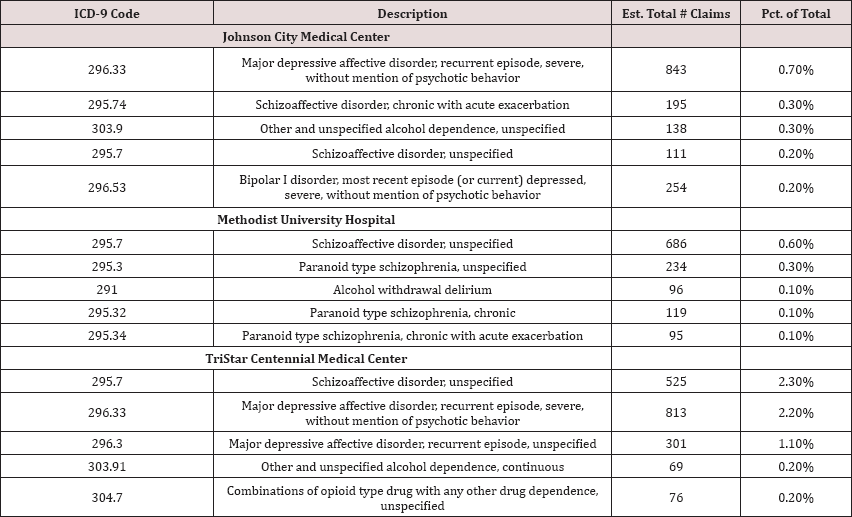

A sample of ICD-9 codes were taken from the top three hospitals in Tennessee, USA that have the highest amount of mental and behavioral health ICD-9 codes on claims submitted to Medicare over a 1-year period in 2013. All data is from adults 18 years or older. In Tennessee, three facilities were found to have the highest number of mental and substance abuse diagnoses (Table 2): It is apparent although the percentage of behavioral health diagnoses is a fraction of each facilities total insurance claim, that even a smaller percentage is referred for further psychiatric evaluation. Perhaps if these patients behavioral health information was available, a higher percentage could have been evaluated differently. There is additional data that shows the most common types of behavioral health diagnosis codes at each of the three facilities (Table 3).Individuals with behavioral health problems frequently have additional disorders that run concurrently. The most common co-occurring conditions are substance abuse disorders, mental retardation, and physical disabilities such as traumatic brain injury. Because these behavioral problems are compounded and complicated by these other conditions, people with co-occurring disorders have:

Table 2.

Source: Definitive Healthcare data

Table 3.

Sourcel: Definitive Healthcare data.

i. More frequent contact with the criminal justice system

ii. More behavior problems when incarcerated

iii. More difficulty connecting to effective services in the community upon release

iv. Are more likely to be re-arrested [4].

Results

Examining the data from the 3 TN facilities in Table 3 show an array of mental health and substance abuse diagnosis codes. Many times, mental illness and substance abuse often go together. Studies have shown that 7 to 10 million Americans have at least one mental disorder and at least one substance-related disorder in any given year. Abuse of one or more substances occurs in:

a) 56% of individuals with bipolar disorder

b) 47% of individuals with a psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder)

c) 32% of individuals with depression; and

d) 27% of individuals with anxiety disorder [5].

The data in Table 3 also shows that a common diagnosis between the three facilities is the population of patients who have a schizophrenic diagnosis code of 295.70. It is also the leading diagnosis code for both Methodist University Hospital in Memphis, TN (Shelby County), and TriStar Centennial Medical Center in Nashville, TN (Davidson County). Studies have shown that individuals who are diagnosed with schizophrenia are at an increased risk of violence. In fact, evidence from an Australia study suggests that offenders with schizophrenia have two times more convictions over their lifetime than offenders without schizophrenia when matched for age and neighborhood [6]. A review of 22 studies published between 1990 and 2004 "concluded that major mental disorders, per se, especially schizophrenia, even without alcohol or drug abuse, are indeed associated with higher risks for interpersonal violence." Major mental disorders were said to account for between 5 and 15 percent of community violence[7] . Data on mental disorders and violence was also collected on 34,653 individuals as part of the.com National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. According to one analysis [8] "the incidence of violence was higher for people with severe mental illness, but only significantly so for those with co-occurring substance abuse and/or dependence." A study of 331 individuals with severe mental illness in the United States reported that 17.8 percent "had engaged in serious violent acts that involved weapons or caused injury." It also found that "substance abuse problems, medication noncompliance, and low insight into illness operate together to increase violence risk [9].

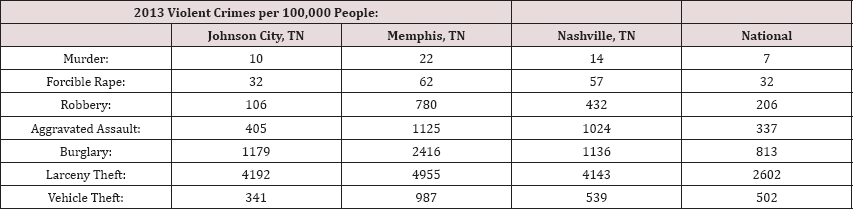

It is imperative that those patients who come into acute care hospital and facility settings with behavioral health diagnoses get additional information from local behavioral health communities to ensure the best care for the patient. Sometimes, seriously ill patients are discharged from hospitals over the objections of psychiatrists who warn that someone may die as a result [10]. For example, in the three cities in TN where there were a large number of behavioral health diagnoses, there were also high rates of violent crimes in those communities that year (Table 4). All three cities have violent crimes higher than the national average, with theft or burglary making up the majority of the crimes. Research has estimated that the risk of an individual with psychosis committing a violent offense compared with a general population group of a similar age is between two and six times for men and two and eight times for women [11].

Table 4.

Sourcel: Retrieved from http://recordspedia.com/TN.

Table 5.

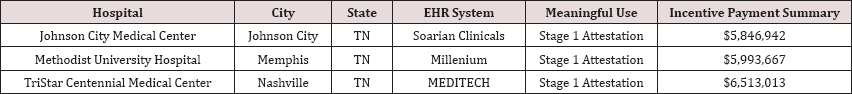

Source1: Definitive Healthcare data.

Discussion

This study has a number of limitations. First, patients were defined by their behavioral health status derived from ICD-9 diagnosis codes from inpatient claim forms. Studying inpatients only, however, gives the advantage of specificity and allows for estimation of the potential impact of any interventions. Second, violent crimes were defined by Tennessee conviction data. Also, the method of population-attributable risk assumes causality. However, the relationship between behavioral health issues and violent crime is more complex, and other risk factors, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, previous criminal convictions, substance abuse, and medication compliance are factors.While there has been significant data presented that detail Tennessee facilities that have high amounts of mental diagnoses claims in their communities and the violent crime statistics in those communities, one must also state the possibility that there may be little or no correlation between the two data sets, but this paper attempts to illustrate that the need for more continuity of care between acute care providers and behavioral care providers is desperately needed. It is public knowledge that all three facilities also have electronic health record systems (EHR) as shown below (Table 5).

Therefore these hospitals have received meaningful use incentive payments to invest into their own EHR systems and infrastructure, however since behavioral health providers are excluded from receiving such payments, these facilities are limited in the information they have on hand in the EHR while treating patients with behavioral health diagnoses. While behavioral health providers are in serious need of EHR adoption (same as the acute care providers), the specific issues that could arise during implementation are different because the acute care community operates in a different manner than behavioral health providers. How one documents a patient interaction into an EHR would be different in a behavioral health setting. For example, many notes are taken regarding patients reactions, comments and conduct during a visit, while the traditional EHR model is focused primarily on documenting physical health status. Another key difference between acute care and behavioral health involves confidentiality laws, which have the potential to be a major barrier to getting behavioral health providers reclassified as acute care providers, thus making them eligible for incentive payments. Without meaningful use payment incentives available to behavioral health providers, there are too many economic barriers for most practices to begin the process of converting to EHR systems. The financing of establishing EHR systems without broader resources available is a major challenge and is slowing the adoption of EHRs among behavioral health providers [1].

Conclusion

To achieve the goals sought after by the EHR incentive Programs of efficiency, coordination and improved quality of care for patients, behavioral health providers, along with the providers of substance abuse, mental health and behavioral health treatment and services, need to be folded into the EHR development and implementation process. There must be increased continuity of care between the behavioral health provider, primary care provider, and other medical specialists in order to improve patient outcomes and potentially help reduce violent crimes in our communities. Perhaps providing better services to people with behavioral health diagnoses in an inpatient setting can reduce incidences of violence.

References

- Getz L (2013) EHRs in behavioral health-a digital future? Social Work Today 13(3): 24.

- Ackerman K (2010) Mental health providers excluded from health IT incentives. In Health beat, California Healthcare Foundation.

- Tennessee (2015) Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. Behavioral Health Indicators for Tennessee and the United States, Data Book, USA, p. 14-36.

- Billings E (2015) Behavioral health acutely needs EHRs. Healthcare IT News.

- Regier D, Farmer M, Rea D, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, et al. (1990) Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the epidemiological catchment area study. Journal of the American Medical Association 264(1): 2511-2518.

- Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P (2004) Criminal offending in schizophrenia over a 25-year period marked by deinstitutionalization and increasing prevalence of comorbid substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(4): 716-727.

- Joyal CC, Dubreucq JL, Gendron C, Frederic Millaud (2007) Major mental disorders and violence: a critical update. Current Psychiatry Reviews 3(1): 33-50.

- Elbogen EB, Johnson SC (2009) The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psych 66(2): 152161.

- Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, Borum R, Wagner HR, et al. (1998) Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and non adherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 155(2): 226-231.

- Zill de Granados O, Rey M (2014) Denied. CBS, United States.

- Fazel S (2006) The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. The American Journal of Psychiatry 163(8): 1397-1403.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

biomedicalengineering@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...