Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Mini Review(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Wellbeing Among Seniors in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of the Literature Volume 5 - Issue 1

Pauline Mulunda Phiri1, Kwadwo Adusei Asante*1 and Eyal Gringart1

- 1School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia

Received:July 28, 2021 Published: August 13, 2021

Corresponding author:Kwadwo Adusei Asante, School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2021.05.000201

Abstract

Factors contributing to the wellbeing of seniors have been the focus of research in recent years. However, literature shows that not many studies have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and this is what motivated the current study. Globally, people are living longer and by the year 2050, it is expected that the population over 60 years will rise to 2 billion, from 900 million in 2015. Considering this, most governments are looking for ways of supporting senior citizens, to help them live in a dignified manner in their retirement years. This is a challenge for most developing countries. While income is important, it is not the only measure of the wellbeing of individuals. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has produced a framework for assessing wellbeing, based on three pillars via which wellbeing can be understood and measured: material living conditions, quality of life and sustainability. A search for studies using keywords that included retirement and wellbeing factors was performed using four databases. Thereafter, articles were selected for full-text analysis. Reference lists of the selected studies were also checked for relevant studies. These studies were then rated for quality based on inclusion criteria. Data were analysed both qualitatively and quantitively to address the research questions. This study is intended to identify gaps in research on wellbeing of seniors on the African continent, which will guide a future doctoral study.

Introduction

This systematic review has been conducted to provide an understanding of how post-retirement wellbeing has been studied previously in sub-Saharan Africa. The current review draws on secondary data to investigate the issue of post-retirement and seeks to answer the following questions:

a) How has retirement in sub-Saharan Africa previously studied?

b) How does retirement affect the wellbeing of senior citizens in sub-Saharan Africa?

From the literature reviewed, the wellbeing of retired individuals in sub-Saharan Africa, like other developing countries, does not appear to have been covered as thoroughly that developed countries [1]. The problem of population ageing is not limited to countries in the West; it also affects nations in sub-Saharan Africa [2,3,], for example, argued that the demographic transition in African countries is being affected by ageing as the continent is seeing a rapid increase of the elderly population [4]. The review of relevant literature starts by analysing the meaning of retirement, senior citizens and wellbeing to provide context to the discussion. The research method is then discussed, to provide insights into how the literature used in the review was selected. The review then examines the literature on wellbeing of retirees using the framework for measuring wellbeing established by the [5]. The review concludes with a data synthesis and discussion of the findings from the systematic literature review, followed by identification of the research limitations as well as implications for future research.

Background

There has been an increase in the life expectancy of elderly people worldwide. In 2015, there were 900 million people aged 60 and above, and this number is expected to rise to 2 billion by 2050 [6]. As a result, studies of retirement are becoming more relevant [7]. In sub-Saharan Africa, the population of older people has doubled since 1990 and is expected to triple between 2015 and 2050 [2]; there were 46 million people aged 60 and above in 2015 and this figure is expected to rise to 157 million by 2050 [8,9]. At age 60, women have a life expectancy of a further 16 years and men have a further 14 years [8,9]. These figures suggest that the wellbeing of senior citizens in developing countries is a matter of growing concern [10]. With the proportion of older people increasing globally, ageing is becoming an important issue for policy makers [9]. Consequently, the wellbeing of seniors has been a focus of research in recent years. This change in demographics is also important for policy makers and researchers in understanding how individuals are preparing for the increase in life expectancy [11]. Various academic fields have conducted studies relating to the increased longevity among seniors. For example, [12] examined how older Ghanaians living in Ghana and Australia interpret active ageing [13]. discussed the public health challenges presented by population ageing.

Defining retirement

Retirement is defined as ‘withdrawal from the work-force altogether or the end of a person’s active working life’ [14]. It can also be considered an event that signals the beginning of a new stage in life [15]. Yet research shows that many retired people reverse their decision at a later stage and return to work [16- 18]. The reasons for such return are varied, including financial need and boredom [18]. While most developed countries such as Australia do not have a mandatory retirement age for the majority of jobs [19], the eligibility age for government benefits is used as the official retirement age [16]. Although the choice of timing of retirement is determined by individuals, it is likely to be influenced by factors such as financial situation, health status, employment opportunities and partner co-ordination [18]. For some people, exiting the workforce occurs when they reach the pension age of 65.5 in Australia (rising to 67 in July 2023); for others, it occurs when they can access their superannuation [20]. Almost all sub- Saharan African countries have a mandatory retirement age, though this varies from country to country [21,22]. For example, in Zambia, early retirement occurs at age 55 while normal retirement occurs at age 60 and late retirement occurs at age 65 [23]. In some cases, individuals choose to transition into retirement by moving from full-time to part-time roles [15]; this phase can be referred to as semi-retirement [15] or partial retirement [17]. There are various reasons why individuals may choose these options. Some opt to reduce their work hours so they can remain in the workforce as a way of keeping the mind active [24]. For the current systematic review, retirement refers to those who have left the workforce permanently. Those that choose to return to work, for whatever reason, are considered semi-retired if working part-time and not retired if working in full-time positions.

Defining Senior Citizens

The term ‘senior citizens’ is used to refer to members of the community who are elderly or of old age [25]. Literature suggests that there is no clear definition of ‘elderly’ or ‘old’ [10]; however, most references to old age by the United Nations and the WHO refer to elderly or old age as those aged 60 years and above [26,9].

Defining wellbeing

There is no universal definition of wellbeing, and some researchers suggest that the concept remains uncertain [27]. This is affirmed by [28], who further stated that it may not be possible to reach a consensus on what the concept of wellbeing means. The challenge in defining wellbeing can be attributed to the different ways in which people understand this concept, which also depends on the context [29]. Despite this, wellbeing is considered an ideal that almost everyone recognises and wishes to attain in their lives [28]. Researchers relate wellbeing to happiness, quality of life or life satisfaction [30]. [29] also relates wellbeing to personal success or happiness, and further states that sometimes wellbeing is equated with life satisfaction, at the expense of other important sides of wellbeing. The OECD has provided a framework for measuring wellbeing [5]. For the OECD, though wellbeing may not have a single definition, there is a consensus among most experts and members of the public that it involves meeting various human needs. Human needs, such as being in good health, are considered essential as they make it possible for an individual to perform other tasks that improve wellbeing, including, but not limited to, being able to work.

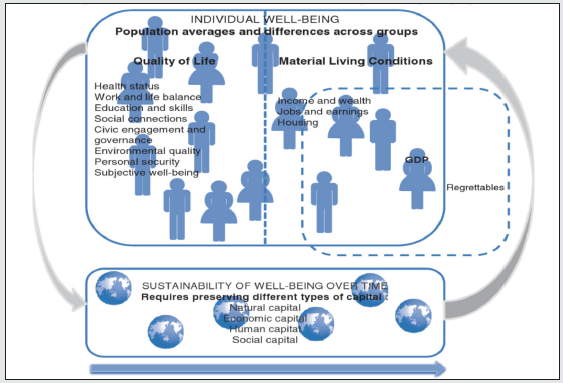

This framework has established three pillars via which wellbeing can be understood and measured: living conditions, quality of life and sustainability. Material living conditions include income and wealth, job and earnings, and housing. These elements are necessary for material wellbeing because they provide individuals with self-fulfillment as well as self-esteem. Quality of life relates to health status, work and life balance, education and skills, civic engagement and governance, social connections, environmental quality, personal security, and subjective wellbeing. Being healthy is important in itself and enables individuals to perform activities that are relevant to wellbeing such as work. Subjective wellbeing includes happiness, life satisfaction and personal affect [31]. [32] confirms that quality of life experiences is associated with feelings of happiness and life satisfaction. The OECD framework includes the ability to sustain wellbeing over time as the third pillar. This relates to how decisions taken today affect the different stocks of capital (i.e. economic, environmental, human, and social) over a period. Although wellbeing may not be easy to define, it is an achievable state [29]. When it comes to retirement, financial satisfaction is not the only measure of wellbeing; reasons for retirement as well as health of the retired individual also have an effect on wellbeing [33]. Thus, the framework provided by the OECD provides important guidelines on what is considered in measures of wellbeing.

Method

Literature Search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across four databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Psychinfo and Proquest. The search was guided by the OECD’s Quality of Life and Material Living Conditions dimensions of measuring wellbeing. Separate searches were carried out using each of the dimensions plus the word retirement. The searches under each dimension were done on Africa first and, if no data were available, the search was opened up to other regions.

Article selection–Inclusion criteria

Articles included were those that were published in English, those that were published in peer-reviewed journals and those based on studies that used each of the 11 dimensions of the OECD framework in the context of retirement. There was no restriction on research design; both qualitative and quantitative studies as well as mixed methods were included. There was no restriction based on gender of participants.

Article selection-Exclusion criteria

Articles that did not include a study or those where studies did not relate to senior citizens were excluded.

Data Extraction

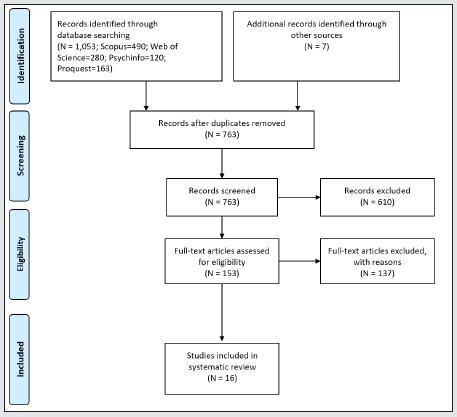

A total of 1,053 articles were obtained from Scopus, Psychinfo, Web of Science and Proquest. After screening for abstracts, duplicated articles and articles that did not meet pre-established criteria were removed. Articles were then selected for full-text analysis. Reference lists of the selected articles were also checked for relevant studies. The studies were then rated for quality based on inclusion criteria. Thereafter, data were analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively to address the research questions.

Measures of Wellbeing in Relation to Post-Retirement Living

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2011)

This review investigates wellbeing in post-retirement, using the 2011 OECD framework. The OECD report does not elaborate on the third dimension-sustainability of wellbeing over time-due to non-availability of data and other logistical issues. As a result, the third dimension is not included in the systematic review.

Quality of life

Quality of life has been established as one of the three pillars of wellbeing [5] and has been examined in relation to post-retirement living. Quality of life is defined by the [34] as:

a) individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationship to salient features of their environment (Figure 1). Used in the American vocabulary at the end of the Second World War, it referred to material goods such as cars, houses and appliances as well as having sufficient resources to live on post-retirement (Alexander & Willems, 1981 as cited in Farquhar, 1995). As noted above, attributes of quality of life include health status, work and life balance, education and skills, social connections, civic engagement and governance, environmental quality, personal security and life satisfaction [35]. These are discussed in turn below (Figure 2).

Health status

Health is an important aspect of life as it enables people to function and contribute to society [5]. Health is vital for the wellbeing of individuals and also enables them to carry out a number of activities that further enhance their wellbeing [35]. For Durand (2015), health status relates to both physical and mental health. Physical health is an important factor in wellbeing postretirement, as confirmed by [36], who assert that good health is one of the factors that contribute to satisfaction in retirement. Further, poor health in older people can be delayed by engaging in physical activities and striving for good nutrition as a way of preventing chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure [9]. Various studies have discussed health status as an attribute of quality-of-life post-retirement. The qualitative and quantitative articles analysed below investigate the importance attached to both physical and mental health.

Qualitative studies

In a qualitative study, [37] examines ‘the beliefs, perceptions and attitudes of two groups of aged males in a semi-urban area of South Africa’ (p. 81). The study has two objectives:

a) to focus on self-perceptions and attitudes of aged males towards themselves, significant others and the process of ageing, and

b) to determine the culturally diverse perceptions and attitudes of aged males towards ageing and concomitant factors.

Two focus groups were formed-one comprising Black African men and the other White men. The participants were aged between 59 and 84 years and each group consisted of 12 men. The use of the qualitative approach allowed the author to gain an understanding of the meanings behind the experiences of the participants [38].

[37] finds that both groups acknowledged that good health, nutrition and exercise were important, and that health played a role in good self-image. The research participants acknowledged that although growing old was a good thing, without health and sufficient financial resources, life would be meaningless. In this regard, research participants who accessed the free services offered by the government found these satisfactory despite the long queues and hours of waiting; while participants who utilised private medical services did not endure long queues, the cost of the services had an effect on their income. The participants had access to health facilities and the choice of using government or private services, which was determined by income availability.

Quantitative study

The effects of retirement on health were the basis for a study conducted in Norway that examined health changes in relation to work exit [39]. It was expected that retirement would have a positive impact on health behaviours and thereby improve health status. The research by [39] compared changes in health of individuals who were still in employment and those who had retired. The researchers purposefully chose participants who were in good health at the time of the study and used data from the Norwegian Study on Life Course, Ageing and Generation. The sample consisted of people aged 40–79 years. Two time periods were used, with T1 occurring in 2002 and T2 in 2007. [39] found that four out of 10 among those who were still in employment and those who had retired reported no change in health status over the period of the study. Most of those who were retired reported that their health improved over the period compared with those who were still working. Retirees also reported an improvement in mental health compared with the employed participants. However, the difference in physical health was statistically insignificant. In considering the findings, the authors also noted the relationship between age and health and that health status is likely to decrease with age. Mental health in retirement years is equally as important as physical health. Chen et al. (2018) examined the relationship between ‘anxiety and depression, the perceived adequacy of retirement savings and self-assessed longevity in China’ [40]. [40] used data from a 2015 survey, carried out in China for individuals 40 years and above, to assess the association between mental health and how financially prepared the participants felt about themselves. The findings from the study showed that, on average, all participants were in good health, but about half felt that they did not have enough retirement savings. The majority nominated their children as their source of support if they needed financial assistance during their retirement years. Apart from assistance from their children, a few expected to receive support from their local government. The results indicated that there was a relationship between mental health and sufficient retirement savings. In this study, [40] found that while financial planning is an important aspect in preparation for retirement, health planning should also be incorporated as part of the process and argued that health promotion strategies should take a longterm perspective similar to the manner in which financial planning is conducted.

Commentary

Although ageing may lead to susceptibility to health disorders, it is possible for senior citizens to continue to experience satisfactory levels of wellbeing even while living with one or more diseases [9]. Nevertheless, access to good medical facilities becomes of primary importance in retirement years. Participants in the South African study by [37] acknowledged this fact and indicated that they had access to the health facilities in their community. The Black African participants in this study utilised the free medical services offered by the government, which they considered satisfactory, while the White participants preferred to use private medical services, which came at a cost. It can also be noted from the Norwegian study by [39] that retirement provides additional leisure time, which, if not used carefully, might lead to activities that damage the health. These could be in the form of inactivity, over-eating, or consuming alcohol. Proper health care is important and the extra time out of the workforce could be used to ensure that this is achieved. From the studies above, it can be noted that good physical health in retirement is just as important as good mental health. The findings by [40] showed that preparing financially for retirement can help to improve mental health, as a lack of financial preparedness could lead to psychological stress. The above discussion corroborates the OECD’s categorization of health as a measure of wellbeing in postretirement. Good health enhances wellbeing and enables people to enjoy a more active post-retirement life.

Work and life balance

Balancing the need to earn sufficient income and the ill effects of too much work is an important issue in modern life [5]. One of the ways in which work, and life balance relates to people in post-retirement or on the cusp of retirement is access to flexible work opportunities. For example, one report has shown that the ‘standard lock-step retirement’ has become less prevalent, resulting in delayed retirement or people taking a flexible approach to retirement [24]. Thus, leaving the workforce is not limited to a set date, enabling individuals to choose when they leave employment and whether they leave on a gradual basis or at once. Although living longer is generally considered a positive, it has the potential to affect public finances. [41] indicate that one way in which this challenge can be managed is by extending working lives. Further, this report states that people in most countries will be expected to work until the relevant pension age or even beyond. The report notes that most countries have increased the state pension eligibility age and, in most cases, aligned these for men and women. While extending working lives is important, the OECD further highlights the need to have employers who are willing to employ older workers. As much as older workers may wish to remain in the workforce, some may face the challenge of age discrimination. [41] acknowledged that, though age discrimination is banned from a legal point of view, its presence is still felt. They further stated that employers show reluctance in hiring older workers as they worry about their productivity. This was confirmed by [42], whose study found that employers were reluctant to hire older workers. The work and life balance dimension of the wellbeing framework has been analysed further in the two qualitative studies below. These studies examined the role played by flexible working arrangements in the choices made by those in post-retirement or those thinking of leaving the workforce on retirement.

Qualitative studies

A Canadian study examined how baby boomers-those born between 1946 and 1965-transitioned to retirement [43]. This qualitative study used online blogging followed by focus groups. Online blogging was used as an interactive method, whereby participants were able to create new online posts as well as respond to posts by other participants. The 25 participants were baby boomers who had recently retired or planned to retire within 5 years of the study.

The findings showed that participants left the workforce through a transition from a full-time position to casual or part-time, ceasing work completely or moving into a different role altogether. Those who chose to retire completely felt that they had worked for long enough and wanted to enjoy their retirement years. Those who opted to move into part-time or casual work wanted to use this option as a way to adjust to retirement. For some, the decision to work part-time or on a casual basis arose because of financial concerns, while for others, it was an opportunity to ease into retirement gradually rather than at once.

In an earlier qualitative study conducted in the United Kingdom, [44] sought to examine the determinants of labour market activity among 60–64 year olds. The study had 96 participants across three contrasting locations and focused on individuals with low– medium incomes, chosen because those with higher incomes would have accumulated good pensions, enabling them to choose when to retire. Flexible work arrangements were regarded as an incentive to encourage retirement-age individuals to keep working. Though the study found that not many participants were interested in working beyond retirement age, for those who were working after retirement or planning to keep working after retirement age, flexible work was their preference. This option was especially attractive to those who had health conditions or were caring for family members.

Commentary

As can be seen from the two qualitative studies above, many retirement-age workers would like to remain in the labour force beyond retirement date. While they may not wish to keep working on a full-time basis, having flexible working arrangements would enable them to transition to retirement on a gradual basis. These individuals seek to work enough to provide them with their required income but at the same time retain sufficient leisure time for their own personal activities. The two qualitative studies were the only ones identified that met the inclusion criteria of this systematic review.

Education and skills

Education and skills have a positive effect on wellbeing in retirement [5]. Among other things, education improves employability. For older workers nearing retirement or those who have retired, education and skills benefit their continuation in the workforce or re-entry for those who have retired. For example, [45] contend that older adults with lower levels of education will face challenges in the future as they will be met with competition from younger employees who are better educated. However, this review did not identify any studies on the ‘education and skills’ dimension in relation to retirement.

Social connections

Social connections are important for wellbeing because humans are social beings for whom personal relationships matter [5]. This dimension of wellbeing is relevant for those in retirement as well as those of working age; as indicated by the OECD report, those over the age of 65 are more at risk of social isolation. Social interaction was identified as a determinant of wellbeing in a study that compared Ghanaians living in Australia and in Ghana [12]. The study participants in Ghana cherished the connections they enjoyed with family and friends while the Ghanaian participants based in Australia wished for those kinds of relationships. [32] also identified social contacts as essential to older people’s social wellbeing. The studies below examined the role of social connections in post-retirement individuals in relation to wellbeing.

Quantitative studies

[46] examined the relationship between retirement and social connectedness, arguing that there is scant research relating to social connectedness towards the end of a career compared with the early stages. For their study, social connectedness was defined broadly as ‘participation in social life’ (p. 482). Their study drew on data from the German Socio-economic Panel Study (GSOEP) and sought to analyse the connection between when exit from the workforce occurs and how socially connected a person is the study’s sample was limited to workers aged 50 and above (capped at 80) as a way of separating retirement from other types of labour withdrawal. Every second year, the primary study included a question on how free time was spent by the participants. The researchers used this information to measure formal participation in social activities such as volunteering in clubs or political organizations. The information was also used to measure informal participation in activities such as social gatherings with relatives, friends, or neighbours. However, [46] admitted that it was not possible to separate work friends from non-work friends.

The results from [46] study showed that there was a relationship between social connectedness and exit from the workforce. However, these effects were dependent on age, and that those older than 60 had a higher propensity to leave the workforce if they had social connections with friends and relatives, which was not observed in people under age 60. The results highlighted the connection between older workers leaving the workforce early to take up leisure time. The authors, however, felt that they could not attribute early exit from the workforce to social connections, arguing instead that there was a possibility that people started taking part in informal social activities in anticipation of retirement. Therefore, they believed that it was possible that early retirement did not occur because of social connection, but rather, that people become more intentional in their social life because retirement was near.

Qualitative study

This qualitative study carried out by Russell (2004) explored elderly men caregivers and their need for social networks. Although mainly discussing caregivers, this study is relevant to this systematic review as it highlighted the necessity of social connection in the elderly. This study had 30 male participants aged 68–90 years and used open-ended interviews. The participants were primary caregivers to their spouses, who had dementia, and were drawn from diverse geographic backgrounds and environments. Two of the participants were still working part-time while 23 were retired. Eight of the 23 had retired early to take on caring responsibilities. [47] found that, of the 30 participants, most identified with feelings of social isolation and loneliness. The role the participants had taken on as caregivers was challenging, both physically and emotionally. Some had continued their social connections with former workmates, while for others, caregiving responsibilities made it difficult to maintain any social networks. For those who did not maintain or establish social connections, their role as caregiver was described as stressful and burdensome. Strydom’s (2005) study in South Africa referred to ‘under health statuses and family relationships. The Black African participants lived in a close-knit family set up with strong family ties and embraced their role as grandparents. In contrast, although the White participants valued their family relationships, they did not have strong family ties; they preferred to ‘stay out of the way’ of their children, and some rarely saw their grandchildren. The White participants belonged to a luncheon club where they met with other senior citizens on a regular basis. Both groups of participants indicated that the concept of engaging in volunteer activities as a form of creating social connections did not appeal to them.

Commentary

The studies above affirmed the OECD’s dimension of social connection and its importance for retirement-age people. Most retired people find volunteering a means of improving social connections. Literature has shown that volunteering has benefits for volunteers and also provides benefits to society [47]. However, in [37] study, the participants indicated that they did not take part in voluntary work as they did not see the need for it. Some indicated that they had worked hard all their lives and just wanted to rest. Others felt that they had their own struggles to deal with and did not see the need to take part in anything that did not provide an advantage to them. Research participants in [37] study did not identify social isolation as an issue. This could be attributed to the Black African participants maintaining social connections through their strong family relationships, while the White participants met with other aged people on a regular basis at the luncheon club they belonged to. The importance of strong family ties for the Black African participants, in comparison to the White participants, may be attributed to cross-cultural differences. People of African origin are said to be of a collectivistic culture, while those from Western cultures are said to be individualistic [48,49]. Collectivistic culture relates to a system that places others as a part of the individual; for example, working together towards a common goal. In contrast, individualistic culture relates to a set of thoughts and feelings that emphasise the importance of the individual (Markus & Kitayama, 1991 as cited in Constantine et al., 2003).

Civic engagement and governance

Civic engagement is important for wellbeing as it gives citizens a political voice, allowing them to contribute to decisions concerning the functioning of society. Likewise, good governance ensures that such voices are translated into laws and statues that enhance quality of life [5]. This dimension of the OECD framework is relevant for both retired citizens as well as younger people. However, for this systematic review, there were no studies found that related to this dimension in relation to retirement.

Environmental quality

Environmental quality is important for wellbeing because it affects people’s health [5]. This is supported by [50], who states that a clean environment is important to health and enhances satisfaction with outdoor leisure. For [51], ‘environmental quality is an important determinant of individuals’ well-being’ (p. 14206). This dimension of the OECD framework is relevant to both retirement-age individuals as well as the younger generation. For this systematic review, there was only one quantitative study that met the inclusion criteria, and this is analysed below.

Quantitative study

In their study conducted in Europe, [51]investigated the effects of air pollution on the health status of senior citizens. [51] used sulphur dioxide and ground-level ozone as the air pollutants. The researchers sought to answer the question ‘How do individuals value the effects on the environment?’ (p. 14206). Instead of being asked about the value they placed on environmental conditions, the participants were asked about the status of their health. Econometric analysis was used to assess how the answers regarding health status shifted because of environmental conditions. Rather than using only one wave of data, the study used panel data to investigate the extent to which air pollution affected health over time. The study used information from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) database, which consists of data on more than 85,000 people aged 50 or over from 19 European countries. The study confirmed findings from previous research that air pollution has an effect on the health status of individuals in a direct and considerable way. The results also showed that people living in urban areas reported low health status levels, which could be attributed to high pollution levels in urban areas because of pollutants such as high population and traffic. The findings of [51] confirmed similar findings in an earlier study; [52] found a relationship between traffic-related air pollution and death from cardiovascular illness. It was also noted that low levels of health status were more likely among older people because of age-related health factors [51].

Commentary

This study confirmed that environmental quality is necessary for physical health. However, it is important to note that while air pollution influences physical health of the elderly, age can also be a factor in their low health status levels.

Personal security

This is a primary element of the wellbeing of individuals [5] and is another important dimension of the OECD framework. Further, Durand (2015) stated that living in surroundings where the likelihood of being robbed is low is important to the wellbeing of citizens. Personal security is relevant for both retired citizens and younger people. However, for this systematic review, there were no studies found that related to this dimension in relation to retirement.

Subjective wellbeing

Subjective wellbeing relates to how the circumstances that people go through are as important as how they experience those circumstances and the view that individuals are the ones who can judge how well their lives are going [5]. Subjective wellbeing incorporates three main components: life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect. Leaving the workforce may have a positive effect on wellbeing as it reduces stress and increases leisure time. However, it may also lead to reduced wellbeing as workers lose social contacts and their sense of identity [53]. Various studies have discussed subjective wellbeing as a quality-of-life attribute in relation to post-retirement individuals; these are analysed below.

Quantitative studies

[54] used a sample of 10,275 Germans obtained from the GSOEP to examine the effect of unemployment on life satisfaction. The participants included men and women between the ages of 50 and 70 years. The study included individuals who were either retired or unemployed. The results from the study showed that those participants who retired voluntarily were better prepared for this phase and therefore had no overall drop in life satisfaction. Although these individuals would have experienced a drop in income after leaving work, they were compensated for this loss by gains in other aspects such as leisure time. In another study conducted in Australia, [55] concluded that most individuals did not know what their needs would be in retirement and therefore failed to make adequate provisions for that phase of their lives. The study examined how retirement altered the welfare of retired Australians using three different measures: standard of living, financial security and overall happiness. The study used data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey and concentrated on participant responses relating to the 2007 special retirement module. They drew on a sample of 1,344 individual retirees aged 45 years and above. The information obtained was complemented by information from previous waves of the HILDA survey. Those individuals who responded to the retirement module had been retired for an average of 7.4 years. Reasons for retirement varied and included health challenges, work stress, job loss, desire for more leisure time and enjoying a good financial position.

The results from this study showed that most of the respondents felt that their wellbeing in retirement remained the same or improved compared with their pre-retirement period. The majority confirmed an improvement or no change in relation to their standard of living, with only a few reporting a decline. In relation to financial security, more than half the respondents reported no change or an improvement. Regarding overall happiness, more than half reported an improvement while one-third reported no change and only a small number reported a decline. This was attributed to the appreciation of other aspects of retirement such as more leisure time, which was spent with family and other social connections. The reason for retirement had an effect on how people felt about their wellbeing in retirement. For those who retired due to health reasons or job loss and ended up with a lower income in retirement than previously, retirement affected their wellbeing, though not in a significant way. [56] examined the connection between retirement and subjective wellbeing, focusing on individuals who were close to retirement and those who had retired. The study used data from the US and 15 countries in Western Europe. The data used for the study were drawn from the 2006 SHARE for 14 European Union countries, the 2006 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) for the UK and the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS) for the US. They used a quasi-experimental design to investigate the relationship between subjective wellbeing and quality of life in an international context. The participants were aged between 50–70 years old and were all men, as women in this cohort were believed to have ‘a weaker relationship with the labour market’ (p. 129).

The subjective wellbeing measures used in the study were life satisfaction and the CASP scale – Control, Autonomy, Selfrealisation, and Pleasure. These components are defined as follows: ‘Control is freedom from constraints imposed by family or lack of money; autonomy can be defined as self-sufficiency; self-realization is focused on enthusiasm about the future; and pleasure refers to finding life enjoyable and fulfilling’ [56]. Three main findings emerged from this study. The first was a significant improvement in subjective wellbeing in the period surrounding retirement. The second revealed a sharp decline in subjective wellbeing a few years after retirement. The third was a neutral position in subjective wellbeing in those situations where incentives were provided to workers who chose to stay in employment instead of taking early retirement. The rapid decline in subjective wellbeing in the years post-retirement suggests that, at the time of retirement, people go through a honeymoon stage, which is followed by a sharp decline before stability is regained [57].

Commentary

The above studies indicate that the reason for leaving the workforce influences subjective wellbeing. Those who left work for reasons other than reaching retirement age or by their own choice found that retirement reduced their wellbeing. It can also be seen that having additional leisure time often compensated for the loss in income that came with retirement. While results from quantitative studies can be generalised across the study population, a qualitative study to understand the meanings that people place on subjective wellbeing in relation to retirement is needed [38].

Material living conditions

Material living conditions is the second pillar of the wellbeing framework; it encompasses income and wealth, job and earnings as well as housing [5]. These dimensions are analysed in detail below.

Income and wealth

Individual wellbeing is reliant on income and wealth generated by the household as this leads to the ability to meet basic financial needs [5]. Income also leads to greater availability of options regarding lifestyle choices. Although income is not the only determinant of wellbeing, it is important for meeting daily lifestyle expenditure needs such as food and housing [58]. Household wealth, comprised of personal savings as well as inheritances, is also important for wellbeing [5]. The OECD further contend that wealth is necessary for ensuring that individuals can sustain their material living standards for a long period. Income and wealth are necessary in retirement, as they are during working lives; though retirees no longer have the capacity to earn an income through employment, their living expenses still need to be met. The literature shows that in high-income countries such as the US, subject to eligibility, one of the main sources of income post-retirement is social security benefits through the government [59]. This income is in addition to pensions through employment schemes and income from personal savings or assets. For sub-Saharan Africa, income sources mainly include ‘employment-related, universal and meanstested systems’ [60]. Employment-related systems are retirement benefits provided through the employer, universal systems are government benefits provided without taking into account the person’s income, employment or means, and means-tested systems take into consideration the person’s or family’s financial resources. The limitation of both universal and means-tested government payments is that they lack adequate coverage [3]. For example, of the 50 countries covered in the report, only 11 provide either a means-tested or universal benefit program or both [60]. No studies fitting the inclusion criteria of this review pertaining to Africa or any of the developed countries were found in the database search. The only available article was the qualitative study discussed below, which was based on a study conducted in Mexico.

Quantitative study

The objective of [1] was ‘to provide a detailed quantitative description of their [Mexican’s aged 50 and over] economic security’ (p. 60). The study used data from the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS), which was aimed at individuals aged 50 and above. The study covered the period 2001–2012, longitudinally following the participants aged 50 and older in 2001 and comparing the follow-up data in 2012 to examine the differences in their economic situation. During the period of the study, the Mexican government introduced a non-means-tested pension program that benefited those who were aged 70 and older; this was thereafter extended to those aged 65 and above. At the time of the findings (2012), the minimum age of the participants was 61 years, with an average of 71.3 years. As the respondents moved through the cycle, the composition of their income source changed from job earnings to pension income and family assistance. Income from investments was low, indicating that the value of the financial assets held by the respondents was minimal. The study found that the most vulnerable were women, rural residents and those who were deemed the oldest; this was because these groups had lower income levels and value of assets. The study also found that as this group of people grew older, they became more reliant on financial assistance from family members.

Commentary

Income and wealth as a dimension of wellbeing is relevant post-retirement as it is how retired individuals support themselves during their retirement years. In a developing country such as Mexico, there is much dependence on family assistance for income. This is different from developed countries, where some can draw on government benefits, employment-related benefits and income from investments.

Job and earnings

The OECD framework identified that having a job and the accompanying income were vital to individual wellbeing [5]. For this systematic review, however, there were no studies found that related to this dimension in relation to retirement. This could be attributed to the fact that jobs and earnings may be considered irrelevant post-retirement. Yet, in countries where there is no mandatory retirement age, individuals have the option to keep working until they feel that they are ready to exit the workforce. For as long as these people continue to work, they will have the ability to continue earning an income.

Housing

Housing provides shelter, a place to sleep and a sense of security; it is considered a basic necessity [5]. This dimension of the OECD framework also identifies the importance of good housing quality as this has an effect on both physical and mental health status. This is also alluded to by [61], who stated that housing is humanity’s basic need in addition to food provision. [61] further states that housing is an indicator of standard of living and of an individual’s status in society. In addition, the OECD report indicates that housing costs can be high, potentially affecting the material wellbeing of the household [5]. Housing is a necessity for individuals at different stages of their lives. According to United Nations data, a large number of older persons in developing countries live with their adult children, with only about 10% living alone [26]. In the South African study by [37], housing was one of the areas included in the research; this is discussed below.

Qualitative study

[37] study investigated the ‘beliefs, perceptions and attitudes of two groups of aged males in a semi-urban area of South Africa’ (p. 82). This study consisted of two focus groups – one with 12 male participants from the White community and other with 12 participants from the Black African community. The White participants all lived in their own home, either alone or with their spouse. On the other hand, the Black African participants had mixed living arrangements. Of the 12 men, four shared their own home with their spouse, children and grandchildren, two lived with their children in their home, and four lived on their own. Both groups of participants felt that having their own place to live made them feel in control. While the White participants were opened to living in aged care homes, the Black African participants were against the idea. Even when their home was not big, some of the Black African participants shared it with other family members. In contrast, the White participants lived in much bigger homes, either on their own or with their spouse only. This was mainly attributed to the differences in how the two groups viewed family. While both groups valued family relationships, the Black African participants held family in more esteem; to the extent that sharing their home was part of that family connection. For the White participants, sharing their home with other family members was not something that they cherished; they valued their independence more.

Commentary

In this study, which compared White and Black African participants living in the same country, housing was indeed a basic need. While both groups preferred having their own place to live as a way of being in control, the Black African participants did not mind sharing their home with other members of the family. This could also be the reason why Black African participants were not open to the idea of aged care accommodation as they probably believed they would be looked after by family members if required.

Discussion

Implications for future research

This systematic review forms the foundation of a doctoral study of seniors in sub-Saharan Africa. As indicated in this review, the issue of population ageing is a global phenomenon; however, there appears to be insufficient research on this topic in relation to developing countries [1], including nations in the sub-Saharan region. Population ageing is likely to have implications for the wellbeing of senior citizens in the various sub-Saharan African nations. There are also potential policy challenges for governments that will need to be addressed to improve the wellbeing of senior citizens. The future PhD research will seek to contribute to social policy discussions on how sub-Saharan Africans living in Western Australia are preparing for retirement.

Research Limitations

The main limitation of this review is that most literature used was drawn from studies conducted in regions other than sub- Saharan Africa. As indicated by [62], because of the significant differences between the two, many concepts of the Western world cannot be adapted to the African situation. For example, the South African study by [37] highlighted cross-cultural differences between Black African participants and White participants. [1] also noted that it was doubtful whether findings from research done in industrialised countries could translate to developing nations. Therefore, findings from the Western context may not necessarily translate to sub-Saharan African countries.

Data synthesis

The systematic review methodology was used to investigate how retirement in sub-Saharan Africa has previously studied. It also examined how retirement affects the wellbeing of senior citizens in sub-Saharan African countries. The wellbeing of senior citizens in retirement was analysed using the [5] framework for measuring wellbeing. Of the 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review, only one directly related to sub-Saharan Africa; the other studies were mainly conducted in developed countries. This does not mean that there has not been any research done regarding retirement in sub-Saharan Africa; however, it may imply that this is an under-researched area, on which more study is required. It could also be related to limitation of the studies identified because of the keywords that were used in the database search. The study that related to sub-Saharan Africa was conducted in South Africa by Strydom (2005) and used the three dimensions of the OECD framework for measuring wellbeing (health status, social connections, and housing). The findings from this study corroborated the OECD’s categorization; with social connections and housing, however, there were cross-cultural differences that were noted between the Black African and White participants. With regard to social connections, the Black African participants had strong ties to family, in contrast to the White participants. Relative to housing, the majority of the Black African participants shared their home with their children and grandchildren while the White participants lived on their own or with their spouse.

Although the OECD’s framework for measuring wellbeing was not specific to senior citizens, the dimensions under the two pillars of quality of life and material living conditions are relevant to retired people. The findings in this review confirmed that income is not the only measure of wellbeing in post-retirement living and that other elements are important too [30]. Good physical and mental health were identified as vital for wellbeing as these enabled senior citizens to do more in their retirement years than if they suffered poor health. Work and life balance was also identified as important for wellbeing as it provided a way for senior citizens to remain in the labour force beyond retirement date. Work and life balance makes it possible for senior citizens to have flexible working arrangements, enabling them to transition to retirement on a gradual basis. Social connections are necessary for wellbeing; the studies found that most people in developed nations opted for volunteering as a way of improving their social connections. However, this was not the case for the participants in the South African study by [37]. The South African participants did not see the need for volunteering, possibly because the Black African participants had strong family ties while the White participants belonged to a luncheon club, which served as their point of social contact. Environmental quality was identified as necessary for physical health, although it was noted that though air pollution has an effect on the physical health of the elderly, age could also be a factor affecting their low health status. Another important aspect for wellbeing among senior citizens in postretirement was subjective wellbeing. The studies found that the reason for leaving work had an effect on the subjective wellbeing of individuals-those who were forced to leave or left for reasons other than reaching retirement age were found to have reduced wellbeing post-retirement. Income and wealth as a dimension of wellbeing was found to be relevant post-retirement as it provided the means for senior citizens to support themselves during their retirement years. In developed countries, retired individuals were able to draw on government benefits and income from investments as financial support. In contrast, for developing countries, there was much greater dependence on family assistance for income.

Housing is a basic need and essential for the wellbeing of senior citizens. The South African study by [37] found that both the Black African and White participants preferred a place of their own as it gave them control. However, the Black African participants did not have a problem sharing their home with other family members; in contrast, the White participants were not open to this option. All the White participants in the study lived on their own or with their spouse. There were no studies related to retirement for four of the 11 dimensions of the OECD wellbeing measures: education and skills, civic engagement and governance, personal security, and job and earnings. This could be attributed to limitations arising from the keyword database search; alternatively, it could be that, for these aspects of wellbeing, no research has been conducted related to senior citizens or retirement living.

Conclusion

The objective of this systematic review was to understand how post-retirement wellbeing has previously been studied in sub- Saharan Africa. The review was conducted using secondary data from studies conducted based on retirement and the wellbeing dimensions included in the OECD framework. Findings from the studies have been outlined in the discussion section above. This topic will be explored further in future research, to be conducted as part of the main PhD study. Ageing is becoming a vital issue for policy makers, resulting in wellbeing of senior citizens becoming a major focus of research. From the findings of this review, there does not appear to have been much research carried out relating to wellbeing of senior citizens in sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, research on the wellbeing of senior citizens in that part of the world will aim to fill the gap.

References

- DeGraff D S, Wong R, Orozco Rocha K (2018) Dynamics of Economic Security Among the Aging in Mexico: 2001–2012. Population research and policy review 37(1): 59-90.

- United Nations Dept of Economic and Social Affairs (2016) Population Facts No. 2016/1 - Sub-Saharan Africa’s growing population of older persons.

- Darkwa K, Mazibuko F N (2002) Population aging and its impact on elderly welfare in Africa. International journal of aging & human development 54(2): 107-123.

- Pillay N K, Maharaj P (2013) Population ageing in Africa. Aging and health in Africa p. 11-51.

- (2011) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. How's life? Measuring Well-Being. Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development, Paris.

- (2018) World Health Organisation [WHO] Ageing and Health Fact sheet.

- Amorim S M, de Freitas Pinho França L H (2020) Health, financial and social resources as mediators to the relationship between planning and satisfaction in retirement. Current Psychology.

- Aboderin I A G, Beard J R (2015) Older people's health in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 385(9968): e9-e11.

- (2015) World Health Organisation [WHO] World report on ageing and health (9241565047).

- Mugomeri E, Chatanga P, Khetheng T E, Dhemba J (2017) Quality of Life of the Elderly Receiving Old Age Pension in Lesotho. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 29(4): 371-393.

- Pothisiri W, Quashie N T (2018) Preparations for Old Age and Well-Being in Later Life in Thailand: Gender Matters? Journal of Applied Gerontology 37(6): 783-810.

- Doh D (2017) Towards active ageing: A comparative study of experiences of older Ghanaians in Australia and Ghana.

- Suzman R, Beard J R, Boerma T, Chatterji S (2015) Health in an ageing world--what do we know ?. The Lancet 385(9967): 484-486.

- Feldman D C (1994) The decision to retire early: a review and conceptualization. Academy of Management Review 19(2): 285-311.

- Bowlby G (2007) Defining retirement. Perspectives on Labour and Income 8(2): 15-19.

- Davis K (2013) The Age of Retirement (AIST-ACFS Research Project, Issue.

- Maestas N (2010) Back to Work: Expectations and Realizations of Work after Retirement. The Journal of Human Resources 45(3): 718-748.

- Wilkins R (2017) The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: selected findings from Waves 1 to 15: the 12th annual statistical report of the HILDA Survey. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

- Atalay K, Barrett G F (2015) The Impact of Age Pension Eligibility Age on Retirement and Program Dependence: Evidence from an Australian Experiment. Review of Economics and Statistics 97(1): 71-78.

- MLC Super (2020) What is the retirement age in Australia?

- Ngadaya E, Kitua A, Castelnuovo B, Mmbaga B T, Mboera L, et al (2019) PO 8573 Research, mentorship and sustainable development: is retirement age a hurdle to research sustainability in africa? BMJ Specialist Journals.

- (2019) Social Security Administration, Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Africa 2019 SSA Publication No. 13-118903). S. S. Administration.

- (2021) National Pension Scheme Authority [NAPSA]. Revision of Retirement Age. National Pension Scheme Authority.

- Kojola E, Moen P (2016) No more lock-step retirement: Boomers' shifting meanings of work and retirement. Journal of Aging Studies 36: 59-70.

- Collins English Dictionary (2014) Dictionary. com.

- Ban K (2007) World economic and social survey 2007: Development in an aging world. DESA, New York, USA.

- Dodge R, Daly A P, Huyton J, Sanders L D (2012) The challenge of defining wellbeing. International journal of wellbeing 2(3).

- Helne T, Hirvilammi T (2015) Wellbeing and sustainability: A relational approach. Sustainable Development 23(3): 167-175.

- White S C (2010) Analysing wellbeing: a framework for development practice. Development in practice 20(2): 158-172.

- Forgeard M J, Jayawickreme E, Kern M L, Seligman M E (2011) Doing the right thing: Measuring wellbeing for public policy 1(1): 79-106.

- Diener E (2009) Subjective well-being. In The science of well-being, Springer p. 11-58.

- Georgiou J (2009) Quality of Life - Mind or Matter? An Australian Case Study into the Current and Future Needs of Older People. Lambert Academic Publishing AG & Co KG, USA.

- Bender K A (2012) An analysis of well-being in retirement: The role of pensions, health, and 'voluntariness' of retirement. Journal of Socio - Economics 41(4): 424-429.

- (1997) World Health Organisation [WHO] Measuring Quality of Life: The World Health Organization quality of life instruments (the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOQOL-BREF). WHOQOL - Measuring Quality of Life.

- Durand M (2015) The OECD better life initiative: How's life? And the measurement of well-being. Review of Income and Wealth 61(1): 4-17.

- Quick H E, Moen P (1998) Gender, employment, and retirement quality: a life course approach to the differential experiences of men and women. Journal of occupational health psychology 3(1): 44-64.

- Strydom H (2005) Perceptions and attitudes towards aging in two culturally diverse groups of aged males: A South African experience. Aging Male 8(2): 81-89.

- Walter M (2010) Social research methods (2nd ed. ed.) Oxford University Press.

- Syse A, Veenstra M, Furunes T, Mykletun R J, Solem P E (2017) Changes in Health and Health Behavior Associated With Retirement. Journal of Aging and Health 29(1): 99-127.

- Chen D, Petrie D, Tang K, Wu D (2018) Retirement saving and mental health in China. Health Promotion International 33(5): 801-811.

- (2019) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Working Better with Age, Ageing and Employment Policies. OECD Publishing.

- Gringart E, Helmes E, Speelman C P (2005) Exploring Attitudes Toward Older Workers Among Australian Employers. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 17(3): 85-103.

- Genoe M R, Liechty T, Marston H R (2018) Retirement Transitions among Baby Boomers: Findings from an Online Qualitative Study. Can J Aging 37(4): 450-463.

- Vickerstaff S, Loretto W, Billings J, Brown P, Mitton L, et al (2008) Encouraging labour market activity among 60-64 year olds. Department for Work and Pensions, Norwich pp. 531.

- Anderson K A, Richardson V E, Fields N L, Harootyan R A (2013) Inclusion or Exclusion? Exploring Barriers to Employment for Low-Income Older Adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 56(4): 318-334.

- Lancee B, Radl J (2012) Social Connectedness and the Transition From Work to Retirement. The Journals of Gerontology 67(4): 481-490.

- Russell A R, Nyame Mensah A, De Wit A, Handy F (2019) Volunteering and Wellbeing Among Ageing Adults: A Longitudinal Analysis. Voluntas 30(1): 115-128.

- Carson L R (2009) “I am because we are:” collectivism as a foundational characteristic of African American college student identity and academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education 12(3): 327-344.

- Constantine M G, Gainor K A, Ahluwalia M K, Berkel L A (2003) Independent and interdependent self-construals, individualism, collectivism, and harmony control in African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology 29(1): 87-101.

- Kahn M E (2002) Demographic change and the demand for environmental regulation. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21(1): 45-62.

- Giovanis E, Ozdamar O (2018) Health status, mental health and air quality: evidence from pensioners in Europe. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25(14): 14206-14225.

- Raaschou Nielsen O, Andersen Z J, Jensen S S, Ketzel M, Sørensen M, et al (2012) Traffic air pollution and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all causes: a Danish cohort study. Environmental Health 11(1): 60-68.

- Kim J E, Moen P (2002) Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: a life-course, ecological model. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 57(3): 212-222.

- Abolhassani M, Alessie R (2013) Subjective Well-Being Around Retirement. Economist-Netherlands 161(3): 349-366.

- Barrett G F, Kecmanovic M (2013) Changes in subjective well-being with retirement: assessing savings adequacy. Applied Economics 45(35): 4883-4893.

- Horner E M (2014) Subjective Well-Being and Retirement: Analysis and Policy Recommendations. Journal of Happiness Studies 15(1): 125-144.

- Atchley R C (1976) The sociology of retirement. Schenkman Pub Co, Distributed by Halsted Press, USA.

- (2015) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. How’s Life? 2015: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing Paris.

- Dushi I, Iams H M, Trenkamp B (2017) The Importance of Social Security Benefits to the Income of the Aged Population. Social Security Bulletin 77(2): 1-12.

- (2019) Social Security Administration, Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Africa 2019 SSA Publication No. 13-118903). S. S. Administration.

- Adegunleye J A (1987) The supply of housing: A bid for urban planning and development in Africa. Habitat International 11(2): 105-111.

- Kowal P, Dowd J E (2001) Definition of an older person. Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. World Health Organization, Geneva.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...