Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Waste Management Behavior in Ala Ajagbusi, Nigeria and the Elinor Ostrom Common Pool Resource Volume 4 - Issue 2

Saheed Adebayo Abdulwakeel* and Orjan Bartholdson

- Department of Urban and Rural Development, Div. of rural Development, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Sweden

Received:May 06, 2021; Published: May 18, 2021

Corresponding author: Saheed Adebayo Abdulwakeel, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Urban and Rural Development, Div. of rural development. Postal address: P.O. Box 7012, 750 07 Uppsala, Sweden

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2021.04.000182

Abstract

Choosing waste dumping sites indiscriminately is a common practice in the global south rural areas. What is little know in the literatures is how this dumping sites are being managed by those who trash it. This paper explores villagers’ collective management of dumping sites in Ala Ajagbusi. The field survey themes were connected to Elinor Ostrom collective management of the common to understand the waste management behavior of the villagers. The qualitative approach to research was adopted in a phenomenological context, this informed the data collection methods and the interview questions. The field survey shows the villagers collectively burn and liberate waste under power line, dumping sites and inside drainage. The villagers regard the waste in the public spaces as public goods which should be managed by the local government. Their actions are informed by their hazardous awareness of waste.

Keywords:Commons; Household; Villagers; Waste; Ala Ajagbusi

Introduction

Choosing waste dumpsites indiscriminately has been increasingly becoming a common practice over space and over time in Africa [1-6]. This is not only peculiar to rural areas, but a common phenomenon in urban settlements [7,8]. Most urban cities in developing world use open dumping as their major waste disposal method [9]. Mangizvo opined that local governments believe waste disposal method such as open dumping remains best possible practicable in Africa owing to financial constraint, poor political will and faced with growing population. Hence, it is very difficult to have a sustainable engineered landfill. Similarly, the high level of open waste dump has been attributed to rapid rate of uncontrolled and unplanned urbanization in the developing nations of Africa. Gabi and Okojie linked this to excessive population, poor domestic waste management, increasing production of waste materials and amongst other. He submitted that poverty and, lack of technology and efficient management of waste informed African countries of adoption of cheap waste management disposal such as open dumping and open burning with little or no concern to social, economic and environmental impacts. What is little know in the literatures is how those dumpsites are being managed by those who trash it especially where government effort towards dumpsites management is literally zero [10].

Burning of waste in dumping sites is a common phenomenon not only in Africa, but a regular practice in other regions of the world and [11] estimated the total percentage of total waste burned openly alone to be 41% which is about 970 million tons of waste per year. This is significant, it poses threat to human health and environment. It requires serious regulation. In Thailand for instance, not less than 3.43Mt of household waste was burned in open areas in a year. This account for 53.7% of uncollected household waste [12]. Essentially, the burning of waste is not only in dumpsites, but also in roadsides, open spaces and inside water channel [13-15]. In USA open waste burning is also known but, in a different scenario and endemic to rural residents. It is rare to see the kind of Africa open waste burning in USA, the common one is open backyard barrel burning, although illegal. It is cheap, convenient and it is a traditional method of waste disposal [16]. In Latvia, the waste collection is about 60%, this suggests that certain percentage will find its way in dumpsites that might ended being burned in order to reduce the waste in landfill [16]. In rural Romania a significant backyard burning is a common practice among rural households especially where waste collection service is partially covered [17]. Generally, the USA, Canada and Scandinavian countries have almost 100% waste collection rate and incineration is the most popular way of disposing waste in those countries [16]. Open dumping and open burning seem to be cheap and affordable waste management, in reality, they are unsustainable in the context of environment impact and human health, and they are alien to sustainable waste management chain. The practices of waste dumping and burning are considered as waste mismanagement [18]. The practice of open dumping devoid of sustainable waste management chains such as collection, sorting (for possible reuse, recovery, reduce, and recycling), dumping either in an engineered landfill or in an incinerator and either bury or burn.

It is essential to state that the practice of waste open dumping and burning has been linked to several human health problems and environmental degradations. Mihai et al; 2019 submitted that about 14 pollutants are being exposed unto the atmosphere which in turn increasing the public health threats and environmental damage risk at the local scale. Regarding open dumping, the main environmental impacts are air contamination, odors and greenhouse gasses (GHG) emission, vectors of diseases, surface water and groundwater pollution [18]. On a global scale, about 1.4 trillion kg of carbon dioxide (C02) is emitted every year through open burning which is a risk factor for cardiorespiratory failure and climate change associated risks [16]. In addition, 3.6 billion kg of methane is emitted unto the space through open burning per year which is a risk factor also for public health and environmental imbalance [16]. Sanneh et al, 2011 submitted that in Gambia the smoke from waste burning covers parts of residential areas and affecting people’s health. The populace is affected by the smoke from waste burning and the smell of decomposing waste. Run off from the dump site with contaminants dissolved into both underground and surface water bodies, while the leachate contaminates the soil and groundwater and [19] enumerated possible diseases and infections that could be contracted owing to poor waste management and disposal. These include diarrhea, typhoid, cholera, Lassa fever plague, leptospirosis, malaria, yellow fever, and dengue hemorrhagic fever Significantly, many members of society who indulge in open dumping and open burning are aware of hazardous effect of both practices on human health and environment. However, their actions are in contrary to their awareness [20]. Abdulwakeel and Bartholdson identified the need for healthy living as one of the drivers of waste management behavior among householders. Importantly, in the study, the waste is being removed from households for healthy living but dumped in open spaces (a bit far away from the living spaces), and burned in open spaces which is harmful to both human and environment. It can be said that the members of the households are incapacitated about what method of waste disposal suite for human health to choose. This paper attempts to explore individual and collective management of dumpsites by members of households and civil society organization in Ala Ajagbusi Village, Nigeria. It further probe into how these dumpsites and waste burning activities are being framed and perceived. The results are being theorize through the lens of theoretical concept of Elinor ostrom’s common pool resource.

Study site

Ala Ajagbusi is a disputed rural village located in between Idanre local government and Akure North local government; both local governments are units of Ondo State and Ondo state is one of the federating units of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The village is located 30 km southeast of Akure, the capital city of Ondo state. The village receives rainfall all year round, with an average maximum of 258 mm in the month of September and a minimum of 8 mm in the month of January. The average temperatures of the village vary during the year by 3.9o Celsius [21]. The village has more than 500 households with over 6000 inhabitants. A majority of the inhabitants are peasant cash crop farmers who mainly cultivate cocoa and palm trees but have a few fields cultivated for food crop production. Apart from farming, people engage in non-farm economic activities such as telecom accessories trading, mercantile, craftsmanship, and vocational jobs such as automobile repair, barbering, tailoring, hairdressing, welding, etc.

In addition, villagers engage in agricultural processing activities. The village has a periodic market that is held every five days and brings together several smaller villages. In addition, many educational, poultry, and fisheries businesses have emerged within the last two decades. Ala Ajagbusi is a strategic community for Akure indigenes (people who are known for cocoa cultivation in southwestern Nigeria; culturally, they are connected to the River Ala) because of its vast arable land. Migrants, who are mainly from nearby states, are predominantly found in the nonfarm and off-farm rural economic sectors because of Ala Ajagbusi’s well-entrenched inheritance land tenure system. See Figure 1a for the location of Ala Ajagbusi village [22-24].

Theoretical Framework

Elinor Ostrom`s common pool resources; governing the common, the evolution of the institutions for collective actions. Ostrom`s theoretical analysis [25] and he was a response to the work of Hardin 1968, “the tragedy of the common” – degradation of the environment to be expected whenever many individuals use a scarce resource in common. Hardin uses the illustration of the herders, when herders deploy their individually rational strategies introducing more and more cattle in a grazing land, this lead to overgrazing – collectively irrational outcome. All herders suffer delay cost from deterioration. Hardin advocated that the “common” should either be privatized or managed by the state in order to liberate the tendency to free ride and selfish use. In contrary, Ostrom posited that individual efforts to collectively manage the common through a robust institutional arrangement could mitigate what Hardin called the “tragedy of the common”. The common are resources used by several individuals such as ocean resources, river, lakes, forest, land resources, grazing land and a host of others. In addition, Ostrom opines that such are commons because it is difficult to exclude individual from use and the benefit consumed by individual reduces the benefit to others (Figure 1b).

Ostrom presents various assumptions in organizing and governing of the common pool resources collectively by individuals. The assumptions are linked to situations of the appropriators, providers, and producers and the attribute of the resources. An appropriator is the person or group of person who withdraws resource units from the resource system. The resource system is the whole stock of the resources while flow is the withdrew resource unit(s) by individual or group of individuals in the resource system e.g. spaces filled in the parking garage. Providers are those who provide the common pool resources, while the producers are those who ensure sustainability of the resource system. The background information that informed the management of common pool resource assumptions are; the quantity of the resource, the number of appropriators, and the transaction cost of collective behavior, the individual benefits of collective behavior, the attribute of the resource e.g. subtractable or non-subtractable, renewable or nonrenewable, replenishment or non-replenishment, the average rate of withdraw and the average rate of replenishment (Figure 2a). In addition, Ostrom emphasized the importance of internal variables (individual decision) to the outcome of governing the common pool resources. The individual`s expected benefits, expected cost, internal norms (fulfilling the promise, trust, and devoid of opportunistic behavior), and discount rate will affect individual`s choice of strategies. Ostrom opines that when the transaction costs of collective behavior of individual are relatively low, when the benefits are limited to a small number of appropriators, when resource is substantial scarce (Figure 2b), when a reasonable level of trust is guaranteed, when resources are not substantially destroyed, and when there is significant discount rate; the individual will devise institutional arrangement and collectively manage the common pool resources.

Nevertheless, the concept of Common pool resources might not be explicitly fit to understand the objectives of this article, but arguably the central notion of this concept is the possibilities of institutional arrangement to manage the spaces that the villager’s trash with waste such as waterway, under the power line, inside drainage and a host of others, in order to escape the tragedy of those spaces. The first author considers those spaces (land) as commons because they remain resources to the villagers, resources in the sense that these are the spaces where they empty their waste sack and the benefit to one villager reduces the benefit to others as posited by Ostrom with the example of parking garage.

Method

The qualitative research approach was used within a phenomenological context aiming understanding of people’s experience and memories [11]. The analyses on how individuals and other stakeholders manage dumping sites was done through the theory of Elinor Ostrom’s common pool resources with the objective of tighten some of the empirical evidence with the common pool concept scientifically. The data collection was done in phenomenological research design context.

Participants

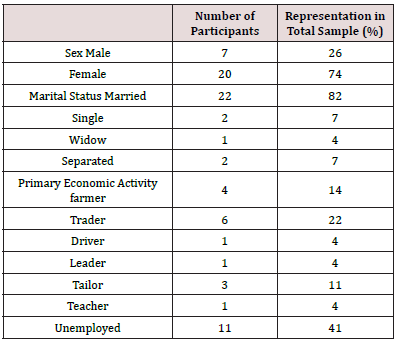

The research informants were selected randomly. The number of women that participated in the research interview and focus group was more than number of men. This is because women are at the center of household waste management processes in Africa [4,6,18]. The first author speaks the language of the villagers and this was a great tool to approach the informants. Informants were informed about the objectives of the research and their consents were sought before the start of each interview and focus group discussion (Figures 3a & 3b). The first author did not use gatekeeper because of the fact the first author speaks the local language [20]. In the interviews and focus group discussions 27 informants were engaged, this represents 0.45% of total population of the village that is put to nearly 6,000. This is similar to a research conducted. The informants were drawn from the three sectors of rural economy: on farm, non-farm, and farm sector. The informant age bracket is between 20 and 65 years of age. See Table 1 below for socioeconomic information of the informants.

Interview

The in-depth interview and focus group discussion were used [16]. The interview questions were not structured, but openended and framed around the objective of the research; exploring villagers’ waste dumping site management and the theoretical concept; Elinor Ostrom’s common pool resource. The field study was done in March and April 2017. During the interview and the focus group discussion informants were allowed to express themselves and gave account of their experiences as it occurred to them. Sometimes, first author would break in when necessary, to further ask question in line with what informant was discussing in order to have a clear picture of informants’ narrative. Questions such as “who chose those dumping sites?”, “who is responsible to liberate waste in public spaces?”, “How do you describe yourself in the village in term of waste management?”, “why some of you trash under power line?” and many amongst others were asked. During the interview there was room for joke and fun without compromising the objective of the interview.

Observation

The first author observed the villages waste management experiences and how the entire village is composed. On many instances, interview outcomes led to visitation of many dumping sites. The entire structure of the village was observed. There were a few instances where informants were interviewed during the observational walk.

Data Analysis

Inductive data analysis was applied to the empirical findings, it simply refers to a process of interpreting data’s meaning with the aim of generating theory from particular to general [16]. The empirical findings were described, reported, analysed and interpreted following the Silverman 2015 suggestion: inductively generating theory from data. The data analysis was done manually rather than with any qualitative data analysis software [17]. The manual data analysis method used in this research is in line with the “three steps” analysis model for data interpretation, as suggested and we structured the materials, connected to themes, and devised categories in relation to the theoretical or conceptual framework.

Findings

Understanding waste

The conscious understanding of waste by the villagers is well related to cleanliness in order not to contract diseases. Villagers are of the opinion that waste should be kept away from the dwellings because non-discarded waste attracts houseflies which could be a vector for certain diseases. Informant W9 stated that ‘we are more than one family living under a single roof; each family is responsible for cleaning the surroundings for one week until the responsibility passes around, and each family is responsible for cleaning their own room every morning’. Informant W1 stated that ‘We cannot keep our waste within the house because of the fear of diseases, but outside the house is good in order to keep diseases away to some extent’. Informant W3 stated that ‘We do keep the waste outside before open dumping in order to avoid diseases. Informant W8 stated that ‘We do clean up our houses for fear contracting diseases’. Informant W9 stated that ‘Dirt can cause diseases via houseflies and harmful insects. The first author observed that there are small open spaces at the back of some houses where the members of the households place their waste unpacked. The first author was told that the waste was left there to dry and it would be burnt later, therefore, it would be safe and not attract houseflies. The understanding of waste as a host for houseflies is not limited to when the waste is placed near a house, but also to when it is burnt, and when it is emptied in an open space far away from house. Whereas in the first author observation, the villagers are more conscious of hazardous effect of waste near the house and when not burn than the burnt waste and waste dumped far away from houses. The informants see waste as a problem especially in relation to diseases. For them when waste is emptied in a dumping site or burnt, they are relieved because they get rid of the waste from the households, but they also know that the waste in the dumping site is a problem, especially in relation to diseases and flooding. Informant W4 stated that ‘waste is commonly emptied into drainage during the rainy season and burnt during the dry season. Yes! this is a problem to human health and environment’.

In addition, many informants said that waste could be recovered or reuse or serve as energy resource. This greatly depends on the type and nature of potentially reused or recovered waste. In most cases, agricultural waste has a greater potential of being recovered or reused or used as cooking energy. ‘Any time we buy something packaged in a plastic container, we reuse it to bottle our palm oil, kerosene, and water until we conclude that it is no longer useful. We don’t discard chaffs from palm kernel and maize because we use it as cooking energy’ (Focus group discussion). In this regard, there two narratives according to the informants concerning harmful awareness of waste. On one hand waste within residence either in waste bowls or on the floor or burnt is more harmful. On the other hand, waste dumped and burnt outside residence is less harmful. Meanwhile, both are harmful. Despite the fact that the informants are aware of harmful of waste, they still indulge in an unstainable method of waste management. The reasons for this might be many, but the obvious one is zero participation of local authority in waste management in the village.

Peoples’ experience

The villagers also recall some horrible experiences. The villagers on the one hand attempt to get rid of the waste and on the other hand escaping the tragedy of others’ poor waste management practices. As stated before empty waste into a drainage is a common practice in the village. When one empties her trash sack into a drainage, somehow she is relieved because she gets rid of the waste, but the waste becomes problem for those living down the street. It is in the sense that many encountered horrible experiences while trying to escape the tragedy of poor waste management practices of others. The common practices here in Ala Ajagbusi is that people often empty their households waste into the drainage in front of their houses during the rainy season and this often causes blockage of the drainage. Thus, it leads to flash flooding having my shops full of water damaging the stocks. In order to avoid this, I have always been in the rain whenever it is rainy to divert the waste being emptied into the drainage. I remember a day when I was diverting the waste I dug my hand into human feces, I hated myself and I was not happy. I had to wash my hand thoroughly with a very strong detergent (Informant W2). Informant W2 wanted to avoid her stocks being damaged by the flood, so she deployed what she knew was best, but she became angry with herself being forced to dig her hand into human feces. In addition, on monthly basis people gather themselves by delegation to collectively burn waste in spaces villagers regarded as public spaces. Informant W4 stated that “The state government sanitation law compels everyone to stay at home between 7:00 AM and 10:00 AM every last Saturday of the month. During this period each household cleans their surroundings, empties the drainage and jointly burns the waste under the power line”.

In addition, one of the disputed traditionally leaders told his experiences with the marketers in the village. He said when it became obvious that the marketers were not heeding to his advice of taking care of generated waste immediately after the marketing session, he singlehandedly organized some youths with the responsibility to ensure cleaning of the stalls by marketers immediately after the marketing session. The youths involved were attacked fiercely by Juju15, and several of them suffered severe injuries. As a leader of this community, we encourage them to clean their surroundings and imbibe the culture of cleanliness. We can only encourage them; we have no power to enforce any penalty. Previously we organized a group of youths to move around the market and some households. The group used to ensure that the market women clean their stalls and households’ members clean their surroundings, but the group withdrew as a result of Juju (Informant M4).

Waste as public goods

Waste has been understood in a different dimension. Waste in the household is seen as household goods and should be managed by the members of the household. In other hand, waste dump at the road side, at the dumping site or in a public space is seen as public goods that should be taken care of by the public authority. One of the informants said that the waste in public spaces i.e. along high way, water way etc. should be reduced or liberated by the local authority. The informant never seen waste reduction in those places as their responsibility. However, their waste reduction actions are informed by the hazardous awareness of waste. This place [pointing to a hill of waste in the wide waterway] is the responsibility of the local authority to manage, but we don’t see the local authority officers and this is where we stay, this is our carpark (NURTW Car Park).

We are clearing the waste in order to escape the possibilities of contracting diseases. This is very close to the union office; we eat and we have our meetings here. Therefore, we have to do that for fear of diseases (Informant M5).

It should be noted that many public entities such as educational space, especially the abandoned section of the only public educational institution in the village is being trashed by students and non-students in the village. It is observed that open defecation is a common practice within this abandoned and dilapidated facility. None of the members of the village including workers of the public school is ready to reduce waste in the facility, they considered renovation of the public school and waste reduction in the facility as local authority responsibility. Sometimes, students are called upon by teachers to burn waste in the facility. It is also said that these students are discouraged sometimes because of too many of human feces in the facility. The zero collection of waste in the village by the local authority suggests serious health and environmental problem.

Discussion/Analysis

Managing the Common

As posited by Elinor Östrom, “commons” are resources that everyone can lay claim to, or resource that its ownership could not be claimed by individuals or groups of individuals. In Ala Ajagbusi, with respect to waste management, “commons” to households are the corridors and the surroundings. On the other hand, “commons” to the entire village are the streets, the waterway and the space under the power line (dumping site). All spaces identified as “commons” are being trashed indiscriminately due the local authority’s lack of waste management arrangement. The members of the households freely trash the “commons” during the day and get it swept before dawn every day in an informal institutional arrangement. The members of the households are synonymous to appropriators while the resource system is similar to the corridor, the surroundings and the disposal sites (land resource) which are “commons”. In the context of waste dumping, the flow of the resource system is when an appropriator withdrawn a unit of resources by dumping waste on a land resource. The space available for other appropriator to dump their waste is considered as resource stock. This is different from another study applying Elinor Ostrom common pool resources on waste management in his research, considered waste as resource (resource for waste pickers who pick valuables from the waste for livelihood), but not pure resources nor mere garbage while this study consider the dumping sites as resources. Supporting argument, it is essential to note that in the Ala Ajagbusi village many agricultural waste is recovered as energy resources for cooking and some plastic materials are reused as liquid containers. Elinor Östrom opines that individuals will devise institutional arrangement and collectively manage the common pool resources when the transaction costs of collective behavior of individual are relatively low, when benefits are limited to a small number of appropriators and amongst other. Importantly, sweeping of the households and burning of waste under power line are waste management behaviors that are relatively low in terms of transaction cost and the benefit is limited to small group of people. In the village only those whose households are very closed to the dumping sites engage themselves collectively to burn waste in those dumpsites. Their actions are informed by the fear of contracting diseases. Further, housewives who are responsible for sweeping households see this as their responsibility with no cost. Also, able men who burn waste see time often spent and cost of Premium Motor Spirit (PMS), which is often use to burn waste, as something affordable.

These two behavior are likened to the institutional arrangement as posited by Elinor Ostrom among the villagers in order to manage the “commons”. Applying Elinor Ostrom’s notion of collective management of “commons”, the first author argues that the villagers are able to devise the collective institution arrangement because of the low transaction cost of sweeping “commons” and the limited benefits to small number of people. In addition, there is reasonable level of trust among the members of households and the resource are not substantially destroyed as posited by Elinor Ostrom. Regarding the low transaction cost, managing the commons in the context of Ala Ajagbusi requires low cost. This is because the cost of materials such as brooms, waste sacks, and plastic parkers are cheap. The smaller size of the family in a household makes collective managements of the “commons” effective as posited by Elinor Ostrom. In what appear contrast, but further buttress Elinor Ostrom argument; when resource is substantially destroyed collectively managing the “common” remain impossible. There are few abandoned dumping sites appear like a dung hill in the village. Managing this land resource, as in to get rid of its waste, remain impossible. This is because the lands have been substantially trashed. When asked about whose responsibility to manage such lands, villagers responded that only government could afford the cost of managing the lands. Which means that the transaction costs for doing this based on local organizing are too high.

Collective waste management

Starting from the notions of cleanliness and dirt, villagers engage themselves collectively to manage waste in a household and by extension collectively manage waste under power line, inside the drainage, and the waste on unpaved road. The collective waste management is often done on the last Saturday of every month to get rid of the waste in the public spaces as stipulated by the sanitation law. In spite of the fact that there are no sanitation officers to enforce the law, members of the households are encouraged by leaders in the village to collectively manage the waste and clean their environment for their own good. Households that are very close to under power line take this responsibility at heart than those living far away from the dumping site. Monthly, households come together by delegating two to three members usually men that collectively manage the waste under power line by burning, burning is the only option available for the villagers. They collectively liberate drainage for free passage of water.

Applying Ostrom notion of the commons, under power line and inside paved roads’ drainage are synonymous to “commons”. In one hand, those spaces are “commons” because no individual could lay claim to its ownership, in other hand, those spaces are resource because of its usefulness for waste dumping. The villagers perceive waste in these commons as public goods that should be managed by local authority. It becomes imperative for villagers to collectively manage the “commons” in the absence of the local authority. The waste as public goods notion of the villagers is similar to the position of Cointreaus-Lev S, the author grouped street sweeping and public area cleaning as public goods in a chat of public versus private in solid waste management. As posited by Elinor Ostrom that when the benefits are limited to a small number of appropriators the collective management of the common would be effective. The first author relies on this notion to argue that the collective efforts are effective because benefits of liberating the drainage is limited to those living in the street and the benefits of burning the waste under the power line is limited to those who are living very close to the dump site. The members of the households living close to the power line see the waste as a threat to their health, this is similar to the research outcome [12]. In this sense, they are much more concerned than those living far away from the power line. It is for this reason that the households’ members engage themselves to burn the waste under the power line monthly. The burning of the waste under the power line and emptying into the drainage are done on monthly basis within three hours. This indicate that participation in the exercise by the members of the households is relatively not difficult. The first author argue that each delegate of the households is able to participate in the collective efforts of burning the waste under power line because of the low transaction cost of collective behavior to all delegates. Despite the fact that they are aware of hazardous effect of waste, they always burn waste. This could mean that they see burning of waste as important than leaving waste in the dump site which could bring unpleasant odour. Although, they are aware of hazardous effect of waste burning, but still go ahead to burn waste. In this context, we argue that the villager’s action is contrary to their awareness [10].

Escaping the tragedy of the commons

Hardin 1968, as described by Ostrom, argues that the tragedy of the commons is inevitable when users of the commons behave opportunistically. He uses herders in a grazing meadow to illustrate his argument. He opines that when herders introduce more herds into the meadow with the objective to free ride, the tragedy of the commons is inescapable. In this sense, Ostrom argues that when appropriators (users of the resource) devise collective management of the commons, the tragedy of the commons could be escaped. This notion can be applied to the collective waste management of the villagers in Ala Ajagbusi. Informants said that poor hygiene is well related to the outbreak of diseases which is synonymous to tragedy of the commons. Informants’ perceptions on the need to get rid of the waste is parallel to the notion of the cleanliness in order not to contract diseases [14-17]. The members of the households sweep their houses and keep waste outside before being emptied into open space for fear of contracting diseases. They say waste can cause diseases via houseflies and harmful insects. Members of the households handle waste in this way in order to escape the possibilities of contracting diseases. On the side of the NURTW, the union handle waste in the waterway for fear of contracting diseases. This is because members eat and attend meeting in the union office which close to the waterway. Applying the concept of the “commons” if the common areas in a household or in a public space are trashed with waste without collective efforts from the members of the households to get rid of the waste. The members of the households or public are vulnerable to tragedy of the commons.

In the context of Ala Ajagbusi, we argue that the informal social arrangement to manage the commons by the members of the households and members of NURTW is synonymous to collective efforts as posited by Ostrom. The objective is nothing but to escape the “tragedy of the commons”. Furthermore, the Market Women Association collectively hire Fulani in the village to liberate drainage in the market, which is trashed by marketers, in order to reduce flooding. In this sense, the effort of Market Woman Association is similar to collective management of the “commons” and the objective of reducing flood is synonymous to “escaping the tragedy of the common” as posited by Ostrom. In the case of households, the objective is not realistic due to poor waste disposal practices, such as burning and dumping, in a space a few meters away from home, and lack of toilet in most houses.

Although, the villagers get rid of the waste in their personal space and household public spaces, but to take it further become problematic. This waste situation is adduced to the absence of state waste management structure. In the case of the village, the market women association and the NURTW, the waste situation is same. This is because the waste situation of individual households is a function of the village level waste situation. Despite the efforts of the trade unions the waste situation remains problematic and very difficult to escape the tragedy of the common.

Conclusion

The research focuses on the waste disposal system in the village in relation to individuals and collective behaviors. It is important to note that waste dumping and burning are common methods of waste disposal in the village, although both are not sustainable methods of waste disposal. All informants are aware of harmful effect of their waste disposal behaviors, but they are more concerned of immediate impact than the future effect, and by the way, they are being constrained with options available to them. It suffices to state that villagers’ actions contradict their awareness, and also state that they are ready to improve upon their waste disposal method if such options are available. They are sufficient with getting the waste out of their households and burning of the waste which considerably reduced waste in dumpsites. As regard the burning, they are aware of its harmful impact, but they need to continue burning because there is zero effort from the local authority concerning waste collection and other waste management chains. Waste management is one of the statutory responsibilities of local authorities in Nigeria. The local authority in question might not have political will to shoulder waste management responsibility in the village. The lack of political will from the local authority might be as a result of poor statutory budgetary allocation, corruption, poor organization management, political rift and amongst others.

Essentially, the framing of the waste in public spaces as public goods by the villagers informed the collective actions of the villagers and civil society organization towards waste reductions in dumpsites. Importantly, the collective waste disposal is possible because of low transaction cost and limited number of beneficiary. This is being demonstrated by the individual villagers living closer to the under-power line, the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW) and the Market Woman Association (MWA).

Acknowledgment

The first author thanks the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) management for the scholarship to pursue a Master by research in Rural Development. First author thanks Fayiq Alghamdi for his materials support.

Author Contributions

The research article was adapted from the master’s thesis submitted by S.A.A. to the Department of Urban and Rural Development, SLU, Sweden. The conceptualization, data collection and writing processes were carried out by S.A.A. O.B. guided and supervised the whole processes of the master thesis.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abdulwakeel SA, Bartholdson O (2018) The Governmentality of Rural Household Waste Management Practices in Ala Ajagbusi, Nigeria. Social Science 7: 90-95.

- Adogu, Prosper Obunikem Uchechukwu, Kenechi Anderson Uwakwe, Nonye Bibiana Egenti AP Okwuoh, Ihuoma B, et al. (2015) Assessment ofWaste Management Practices among Residents of Owerri Municipal Imo State Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Protection 6: 446-456.

- Ala Ajagbusi Climate Data (2017).

- Cave J (2017) Managing urban Waste as Common pool resources. Note from WIEGO 20th Anniversary Research Conference, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America.

- Christine Wiedinmyer (2014) “Global Emissions of Trace Gases, Particulate Matter, and Hazardous Air Pollutants from Open Burning of Domestic Waste”. Environ Sci Technol 48(16): 9520-9525.

- Cogut A (2016) Open Burning of Waste: A Global Health Disaster. R20 Region of Climate.

- Cointreaus Levine S (1994) Private Sector Participation in Municipal Solid Waste Services in Developing Countries.

- Creswell John W (2009) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, (3rd), London: SAGE Publications, Inc, UK.

- Creswell John W (2014) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, California.

- Ferronato N Torretta V (2019) Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues. Int J Environ Res.Public Health 16(6): 1000-1060.

- Forbid GT, Ghogomu, JN, Busch, G. et al. (2011) Open waste burning in Cameroonian Cities: an environmental impact analysis. Environmentalist 31: 254-262.

- Gani OI and Okojie OH (2013) Environmental audit of a refuse dump site in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology 5(2): 59-65.

- Ifegbesan Ayodeji Peter (2010) Solid Waste Management Practices in Two Southwest State, Nigeria: Household Perspective.

- Inglis, David, and Christopher Thorpe (2012) An Invitation to Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity, England.

- Kadfak, Alin (2011) An Analysis of the Social Relations in Waste Management: Two Case Studies on Somanya and Agormanya in Ghana. Master’s thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Manga VE, Forton OT, Mofor LA, Woodard R (2011) Health care waste management in Cameroon: A case study from the Southwestern Region. Resources Conservation Recycling 57: 108-116.

- Mangizvo V. Remigios (2010) An overview of the Management Practices at Solid Waste Disposal Sites in African Cities and Towns. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 12(7): 1520-5509.

- Mansur Aminu (2015) An Analysis of Solid Waste Generation and Disposal in Dutse Sahelian Zone of Jigawa State, Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Crop Sciences 8: 81.

- Mihai FC, Banica A, Grozavu A (2019) Backyard burning of household waste in rural areas. Environmental impact with focus on air pollution. 19th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geo Conference on Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation SGEM 2019 (5.1): 55-62.

- Obionu CN (2007) Primary Health Care for Developing Countries. (2nd), Publishers Institute for Development Studies, University of Nigerian Enugu Campus, Enugu pp: 183-284.

- Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, England.

- Pansuk J, Junpen A, and Garivait S (2018) Assessment of Air Pollution from Household Solid Waste Open Burning in Thailand. Sustainability 10: 2550-2553.

- Sanneh ES, Hu AH, Chang YM, Sanyang E (2011) Introduction of a recycling system for sustainable municipal solid waste management: A case study on the greater Banjul area of the Gambia. Environment Development Sustainability 13: 1065-1080.

- Silverman, David (2015) Interpreting Qualitative Data. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, California.

- Solomon Aisa Oberlin (2011) The Role of Households in Solid Waste Management in East Africa Capital Cities. Ph.D. thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, UK.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...