Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Mini Review(ISSN: 2690-5752)

The Relevance of Durand’s Anthropological Framework of Imaginary in the Understanding of the Paradoxical Dimensions of Frontiers and Boundaries Volume 2 - Issue 3

Christian R Bellehumeur*

- Saint-Paul University, Ontario, Canada

Received: May 26, 2020 Published: June 11, 2020

Corresponding author: Christian R Bellehumeur, PhD, Saint-Paul University, Ontario, Canada

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2020.02.000136

Mini Review

The accelerated proliferation of works on the topics of

frontiers, borders, and boundaries, in geography, political science,

sociology, anthropology and even literary studies, is considerable

[1-5]. In that sense, the challenges and issues related to frontiers

and boundaries are not new: many researchers have addressed this

problem in anthropology [6,7] as well as in archeology [8-10].

These notions of frontiers and boundaries are important for

various reasons such as for the understanding of geographical space

and evolution, any culture of origin and history, for the affirmation

of a nation’s identity, or in the context of cultural exchanges and

social interactions (e.g. immigration, business trades, to name a

few). Indeed, frontiers have many functions or roles depending on

contexts, circumstances, and even people. As Anderson and O’Dowd

[11] have pointed out:

[Borders] are at once gateways and barriers to the “outside

world”, protective and imprisoning, areas of opportunity and/or

insecurity, zones of contact and/or conflict, of co-operation and/or

competition, of ambivalent identities and/or aggressive assertion

of difference. The apparent dichotomies may alternate with time

and place, but, more interestingly ̶ they can co-exist simultaneously

in the same people, some of whom have to regularly deal not with

one state but two.

This short article aims to highlight the relevance of Gilbert

Durand’s [12] anthropological framework of imaginary for

understanding the paradoxical dimensions of frontiers and

boundaries. In order to do so, the complexity and paradoxical

nature of frontiers and boundaries will be presented. Following

that, Durand’s theory on the anthropological structures of the

imaginary will be briefly introduced. Lastly, we will conclude with

an application of Durand’s framework to the notion of frontiers.

The Complexity and Paradoxical Nature of Frontiers and Boundaries

Frontiers and boundaries are not only dynamic over time, they remain fundamentally paradoxical [12] and complex as they can be real or imaginary [13]. In that context, one needs to recognize the importance of imagination (and imaginary)1 to make sense of this complexity [14]. For instance, in times of natural disasters (such as forest fires, earthquakes, and so forth) or even wars, a country opening its frontiers in favor of welcoming strangers-coming from other countries and perceived as victims–would be most likely viewed as altruistic and responsible towards these people. In other circumstances, such as the current worldwide (COVID-19) pandemic, the opposite behavior is expected all over the world. In such cases, countries that maintain firm and clear boundaries, closely monitoring their frontiers, would be considered as acting responsibly, while still being altruistic and respectful of others2

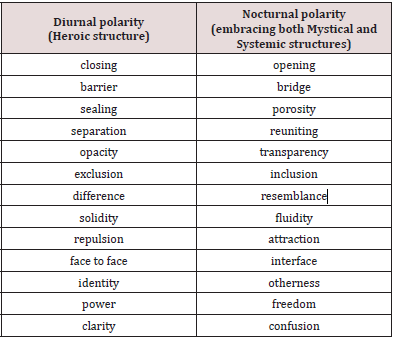

There exist plenty of concepts relevant to the notion of frontiers which refer to a constant dialectical tension; these concepts are expressed by a plurality of polarized coupled terms such as: linezone; closing-opening; barrier-bridge, sealing-porosity; opacitytransparence, separation-reuniting; repulsion-attraction; exclusion-inclusion, face to face-interface [13]. These paradoxical tensions are also seen at the strategic level (e.g. constraints-opportunities; break-leverage); at the identity level (e.g. difference-resemblance; polarization-hybridity; solidity-fluidity; identity-otherness); at the territorial level (e.g. fixity-mobility; power-freedom; institutionssubjects; map-narratives; real-imaginary), as well as at the scalar level (e.g. clarity-confusion; unity-plurality; stability-oscillation) [13].

Despite the fact that all these coupled terms (mentioned above) shed some light on the complexity of the paradoxical aspect of boundaries; they do not provide a heuristic way of making sense of them. In order to provide a more coherent way to deepen our understanding of the paradoxical dimension of frontiers and boundaries, Bellehumeur and Chambers [14] have proposed, in the context of interpersonal and professional boundaries, a transdisciplinary framework, Gilbert Durand’s anthropological structures of imaginary, as a heuristic model that make sense of the various: “functions and meanings of the border [which] have always been inherently ambiguous and contradictory” [11]. We argue that this anthropological framework is also relevant to the notions of boundaries and frontiers at a more macro level (e.g. for ethnographic, historical and sociopolitical research).

A brief overview of the The Anthropological Structures of the Imaginary (ASI)

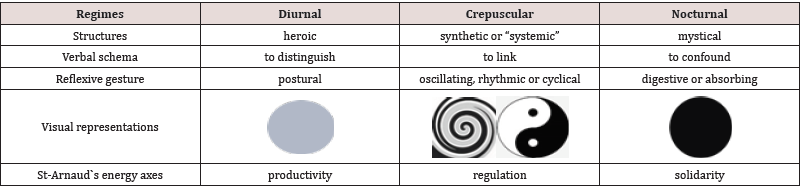

According to Gilbert Durand [12,15] there are, at the origin of human cultures, reservoirs of images and symbols which continue to shape our ways of thinking, living and dreaming. In his seminal work The Anthropological Structures of the Imaginary (ASI), Gilbert Durand [12,15] considers the human being as a homo symbolicus, and demonstrates that there are two great polarities creating mental, visual, and narrative images, which are the diurnal and nocturnal regimes. These polarities are based on opposing worldviews or structures of the imaginary: (a) arising from the diurnal polarity, the Heroic Imaginary Structure of the human imaginary-characterized by the verbs ‘to distinguish’, ‘to separate’, ‘to ascend’, and ‘to purify’-emphasizes actualizing an outcome, striving, initiative and action, separating good and evil, and conquering one’s obstacles. It refers to an energy of “productivity” related to identity [16]; (b) arising from the nocturnal polarity, the Mystical (‘intimist’) Imaginary Structure-characterized by the verbs ‘to confound’, ‘to descend’, ‘to possess’, and ‘to penetrate’- emphasizes intimacy, passivity, refuge as a fortress, peaceful rest, and relaxation [15]. This mystical structure tends to merge things together; it refers to an energy found in “solidarity” [16]. Linking the two polarities, Durand [12,15] also identified a third structure called “synthetic” (later renamed “systemic”) occurring between the nocturnal and diurnal polarities. This requires the co-existence of both heroic and mystical structures, which is best represented by the energy of regulation [16] encountered in the systemic imaginary structure. In this imaginary structure, there is a harmonious coexistence of both imaginary systems without mutual exclusion [12]. This refers to the notion of or dialectics3 [17]or symbols such as the Ying and Yang, or the expression “coincidential oppositorum” (coincidence of opposite elements)-also used by authors like Eliade and Jung-in order to describe the essence of the systemic category. This structure is well described by the verbs ‘to return’, ‘to grow’, ‘to progress’ or processes such as historicity, maturity, via the verbal schema ‘to link’ [12,15]. The visual representations in Table 1 demonstrate the main differences between the three structures.

A light grey color circle is used to represent the heroic structure, as it echoes the diurnal polarity, the verbal schema “to distinguish,” and also resonates with St-Arnaud’s concept of energy of productivity and constant tension of living, as mentioned below. A darker (black) circle is used to represent the mystical structure, as it echoes the nocturnal polarity, the verbal schema “to confound” and at the same time resonates with St-Arnaud’s energy of solidarity, harmony and peaceful living. Finally, in the middle, a swirling circle with both the light and the dark colors is used to represent the systemic structure as it echoes the verbal schema “to link,” and also resonates with St-Arnaud’s energy of regulation. Note that in the systemic structure, there is no “blending” of the two polarities (which would best be represented by a darker tone of grey circle, blending light grey and black); instead, the swirl illustrates the harmonious co-existence of opposites.

An application of Durand’s Framework on the Notion of Frontiers

To illustrate our view and to apply it to the notions of frontiers, one can see in table II how Durand’s theory provides a useful framework to account for many (yet not all) of the polarized terms expressing many features relevant to boundaries. Looking at this table, one can appreciate how the full spectrum of these various features of boundaries require the coexistence of both heroic and mystical structures, which is best represented by the energy of regulation [16] encountered in the systemic imaginary structure (Table 2).

Conclusion

In this short article, we sought to demonstrate the relevance of Durand’s anthropological structures of the imaginary framework as a useful model for making sense of the complexities related to the paradoxical dimensions of frontiers and boundaries. Given the fact that the notions of frontiers and boundaries have recently become more relevant and crucial with regards to maintaining people’s needs for security (mostly for public health reasons), on top of their needs related to belonging and identity [18], the heuristic potential of Durand’s framework appears to be a remarkable conceptual resource to explore within that context.

References

- Kolossov V (2005) Theorizing borders. Border studies: Changing perspectives and theoretical approaches. Geopolitics 10: 606-632.

- Newman D (2006) The lines that continue to separate us: Borders in our "borderless" world. Progress in Human Geography 30 (2): 143-161.

- Rumford C (2006) Theorizing borders. European Journal of Social Theory 9 (2): 155-169.

- O’Dowd L (2012) Contested states, frontiers, and cities. In TM Wilson and H Donnan (Eds.), A Companion to Border Studies. Blackwell, London pp. 158-176.

- Wilson TM, H Donnan (Eds.) (2012) A Companion to Border Studies. Blackwell, London.

- Watson G (1984) The Social Construction of Boundaries between Social and Cultural Anthropology in Britain and North America. Journal of Anthropological Research 40 (3): 351-366.

- Martin D (1990) Anthropology on the Boundary and the Boundary in Anthropology. Human Studies 13 (2): 119-145.

- Green SW, SM Perlman (1985) The Archaeology of Frontiers and Boundaries. Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Lightfoot K, A Martinez (1995) Frontiers and Boundaries in Archaeological Perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1): 471-492.

- Vis BN (2018) "Understanding by the Lines We Map: Material Boundaries and the Social Interpretation of Archaeological Built Space". In Siart C, Forbriger M, Bubenzer O. (eds) Digital Geoarchaeology. Natural Science in Archaeology, Springer, Germany pp. 81-105.

- Anderson J, L O’Dowd (1999) Borders, border regions and territoriality: Contradictory meanings, changing significance. Religious Studies 33 (7): 593-604.

- Durand G (1999) The anthropological structures of the imaginary. (translated by M Sankey & J Hatten from the 1992 French version). Boombana Publications, Brisbane, Australia.

- Brosseau M (2014) Le Paradoxe de la frontiè In A Gilbert, et al. (Eds.). La frontière au quotidien. Expériences des minorités à Ottawa-Gatineau. Les Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, Canada.

- Bellehumeur CR, J Chambers (2017) "Contributions of sensory anthropology and Durand’s anthropology to the symbolic study of touch and the understanding of professional boundaries in psychotherapy." In M Rovers, et al. (Eds). Touch in the Helping Professions. Research, Practice and Ethics, University of Ottawa Press, Canada p. 51-68.

- Durand G (2016) Les Structures anthropologiques de l’imaginaire: Introduction à l’archétypologie générale. Dunod, Paris, France.

- St-Arnaud Y (1989) Les petits groupes. Participation et communication. Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal et Les Éditions du CIM.

- Lomas T, Ivtzan I (2016) Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive-negative dialectics of wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 1753-1768.

- Meier A, M Boivin (2011) Counselling and Therapy Techniques. Theory and Practice. Thousands Oak, Sage Publications Inc, USA.

- Durand G (1979) Figures mythiques et visages de l’œuvre: De la mythocritique à la mythanalyse, « L’île verte », Berg international, Paris, France.

- Durand G (1992) Les Structures anthropologiques de l’imaginaire: Introduction à l’archétypologie géné Dunod, Paris, France.

- Durand Y (2005) Une technique d’étude de l’imaginaire: L’AT.9, Harmattan, Paris, France.

- Hall ET (1966) The Hidden Dimension. Doubleday, Garden City, New York, USA.

- Merriam-Webster dictionary.

Footnotes

1As opposed to one individual’s particular imagination, the term imaginary (from the French noun imaginaire”, and not its adjective equivalent), refers to the general and collective human ability to imagine which Durand (1979) calls “the whole human universe” (p. 23); it is a dynamic force that creates images and symbols and is represented by particular verbs and actions.

2The practice of “social distancing” renews the importance of the works of the famous American anthropologist and cross-cultural researcher, E. Hall, on proxemics and how people have to behave and react in different types of culturally defined personal space (Hall, 1966).

3Dialectics in the Merriam Webster Dictionary (2020) refers to the “dialectical tensions or opposition between two interacting forces or elements.” For instance, positive and negative emotions are opposites, but they are also intimately connected. Their relationship is not static but continues to evolve through the interplay of the two polarities (Lomas & Ivtzan, 2016).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...