Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Review ArticleOpen Access

Living in the Anthropocene Volume 1 - Issue 2

Jesse Negro*

- Department of Anthropology, Macquarie University, Australia

Received: November 23, 2019 Published: December 04, 2019

Corresponding author: Jesse Negro, Department of Anthropology, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Introduction

The Anthropocene is the proposed geological epoch where humans have changed some of Earth’s systems. There are many debates surrounding the Anthropocene from if it is a new geological epoch, if it is a new epoch when did it begin and the distinction between nature and human made [1]. Cities have had a major environmental impact across the world, shaping the physical geological environment and could be considered monuments of the Anthropocene. During the Anthropocene, humans have shifted from nomadic and rural lifestyles towards hunting in the big city. Rapidly increasing city populations has placed further pressure on the environment and according to Davis [2], the urban population at the time of his work was 3.2 billion. Davis [2], predicts that cities will account for all future world population growth, which is expected to peak at 10 billion people in 2050. As this growth continues, we will see the rise of megacities (population of 8 million) and hyperscities (population of 20 million). Shanghai’s population could rise to as many as 27 million people and Davis [2] begins question whether such large populations are biologically or ecologically sustainable. Across the world we are beginning to see a green architecture movement aiming to lessen the impact cities are having on the environment. Green architecture is an example of cultural niche construction in modern urban environments. Laland and O’Brien [3] argue that human niche construction through modifying the environment there is the creation of artefacts and ecologically inherited resources that not only place pressure on gene selection but also facilitate learning and mediate cultural traditions. In demonstrating this argument Laland and O’Brien [3] use the example of the construction of urban spaces such as villages and towns, which present new health hazards such as the spread of epidemics. Humans can respond to these selective pressures through cultural evolution constructing hospitals and developing medications. Each city presents its own set of challenges when considering green architecture, which include ecological, economic and cultural challenges. The aim here is to investigate the relationship between human and non-human in green urban environments. Macquarie University in Sydney makes a good field for this project as there are numerous examples of green spaces such as the library that have used green architecture, a variety of themed gardens, manmade water features and large quantities of plant life amongst a range of buildings located in the hub of Macquarie Park.

The Field

Figure 1: Map of Sydney showcasing Macquarie University’s location. (Source: google images. Image by GEMOC Macquarie University).

The sound of raging cars pierces through the thick smog of the formally crisp morning air. There is seemingly no hiding from the noises, the smells or the sights of the city. Whether we live in a studio apartment with a pocket-sized window or a top floor penthouse with more bedrooms than people we all face the same concerns in an urban environment. As the day progresses, we navigate the city using various modes of transport, a variety of steel boxes powered by burning fossils and electric currents try to mask us from these toxic interactions, but these come with their own set of issues. We follow paths that have been carved through the surface of the Earth and held into place with concrete; they feel cold and are so dark they appear endless. Delays are inevitable whether it’s bumper to bumper on congested roads or shoulder to shoulder on a stressed public transport system. Finally, an automated computer system tells that we have reached our destination and for some this simply means they will spend the next portion of their day in steel and concrete monuments with the next thing to look forward too is the same arduous commute home. However, for others when they exit their modes of transport suddenly there is space, the air is fresher and the sights more scenic. The emergence of green architecture in urban environments has many benefits, which students at Macquarie University get to experience every day on campus. Macquarie University is located 40 minutes North of the Sydney city central business district (Figure 1).

The University attracts students from Sydney’s West, North, East and South as well as International students from all corners of the Earth. The University is surrounded by concrete monuments in every direction from the growing Ryde and Hornsby business and residential districts. The University Library is a premium example of green urban space as it utilizes a range of sustainable elements such as construction, water recycling, power conservation, innovative technology and green spaces predominantly the green roof. Sustainability was a key aspect of the library’s construction with 80% construction waste being recycled [4]. The production of both concrete and steel consumes a lot of energy and produces high carbon emissions. The University combated this concern by using recycled materials to save on the production of new materials for the library. Meticulous planning was not only put into the construction of the library but also the design of the library. The library was designed with a glass facade to allow in maximum levels of light to save on energy used to produce artificial light [4]. To allow natural light through the entire building two wells are located in the middle of the library that makes use of large windows spreading light through the building. The final element of the library’s design covered here is the roof, it is unlike many other examples of green architecture that line their roofs with black solar panels. The library features a green roof, which makes use of native plants providing an irrigation system for the 300 000-liter water tank that sits beneath the library [4] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Part of Macquarie University’s green roof. (Source: Macquarie University. Image by Macquarie University.).

The water tank reduces the amount of water the University takes from Sydney’s water supply by using the water for university toilets and watering the University’s other green spaces such as the gardens and grass. While environmental, economic and social benefits are important aspects of green architecture in the Anthropocene, the element that is most often missing is the way humans utilize and connect with spaces [5].

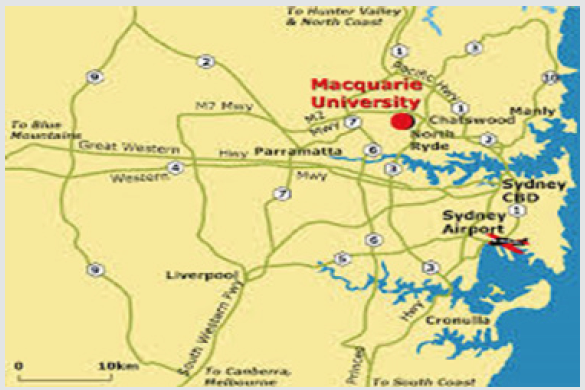

Across the first semester of 2016 at Macquarie University I used three different locations across the campus for participant observation sites; the library green roof, Macquarie University’s lake and Wally’s walk which intersects with three of the university’s native gardens. I visited each site twice for an hour in the two weeks that followed the mid-semester break. Despite the university website suggesting that green roof had also been designed for informal study, social gatherings and university club and group meetings there was little to be seen in my observations in week 7 and week 8. I observed the site between 12:30 and 1:30 pm when the University is usually at its busiest, both days the sun shone brightly, and the temperature sat comfortably at 23 and 26 degrees Celsius respectively highlighting no obvious reasoning for the lack of engagement with the green roof. I visited my second site on the same days between 11:15 and 12:15 pm, the lake is located adjacent to the food court and central hub. During these periods of observation, I began to notice several behavior patterns; across both observations 122 people sat on the grass between the lake and the central hub mostly to eat their lunch. However, as more people gathered it became evident that people did not want to sit next to the lake, there was an approximately 15-meter gap between the lake and the closest group of people. There were several individuals who were able to break this invisible barrier if only for a few seconds to take their phone out and take a picture before retreating to their group. The final site I observed was Wally’s walk between 2:30 and 3:30 pm and on both occasions a university group was served chai tea on the grass. The remainder of the grass was covered in a thick undisturbed blanket of leaves that had fallen from the surrounding trees. This space has four benches and tables that have been used to promote multifaceted use such as eating, studying and recreational activities. Wally’s walk appeared to be a high traffic area for the university with streams of students walking between the surrounding buildings and stopping at the coffee cart next to student connect. As I continued to observe I noticed that people were stopping for more than just coffee, in the middle of the walkway people would stop with their friends pointing towards the garden with many even pulling out their phones to take pictures before continuing without engaging further with the space. Participant observation studies have many advantages and disadvantages which I encountered during my visits to the field. Observation is unobtrusive meaning there is little to no manipulation of the participants and there is no rigorous ethics approval required. Critiques of observational approaches have been that they are unfalsifiable, generating debate over key findings and analysis of behaviors [6]. Understanding the relationship between humans and green built environments requires more than observational behavioral analysis. Critical discourse analysis stems from theory of language that views the use of language as a social practice [7]. Through analyzing language used to discuss green urban environments at Macquarie University I was able to uncover new insights into the way humans use green urban spaces. Table 1 below demonstrates a sample of the different ways people think about, discuss and use green spaces at Macquarie University.

Participant observation and discourse analysis revealed that people who visit Macquarie University do engage with many of the green spaces that are available. However, the engagement with the spaces tends to be superficial with spaces being used for photo opportunities instead of their primary social function. There are numerous barriers that cause a superficial engagement which include lack of facilities on the green roof such as chairs, benches or shade deterring people from using the roof as a studying or social space. Secondly many of the green spaces such as native gardens and the green roof are well hidden meaning that many people who come to Macquarie University regularly may not know that they exist. Thirdly some forms of wildlife particularly birds encourage people to look for other spaces as they associated with many common fears such as being swooped or having food stolen. Finally, some social media commentary identified litter as a deterrent from using green spaces on campus. The commentary specifically mentions smoking and cigarettes as a key issue as both an aesthetical and health concern. Does this mean spaces were designed with the wrong functions in mind? Are the spaces not promoted correctly? How much do our relationships with green urban spaces matter if they are providing environmental benefits? In addressing these questions, we will begin to broaden its field to analyses if there are similar concerns with green urban spaces around the world.

Broadening the Field

Cities around the world are beginning to turn to green architecture to function in what would be considered a good Anthropocene. Living in a good Anthropocene is more than reducing carbon footprints through recycling energy and sustainable construction. The second part of a good Anthropocene is humans being able to positively interact with green urban spaces generating social benefits. Humans interact with the built environment in many different ways; typically, this will involve changes in designs or construction to solve problems that are plaguing the community. Illness and Health are two key factors that have been behind changes to urban environments. An early example of this type of change is in 19th century London where an outbreak of cholera which people believed these foul smells or miasmas, prompting improvement of infrastructure such as waste disposal essentially shaping what we view as the modern city [8]. Modern cities are becoming plagued with different kinds of illnesses specific to urban environments that impact on humans’ mental health and lack of physical activity. According to the World Health Organization, physical inactivity is a major public health risk. In Australia half of the population does not reach the 30 minute daily physical activity recommendations. A study found that people who use green urban spaces are three times more likely to achieve recommended levels of physical activity than those who do not use the spaces [9]. Urban environments have high incidences of schizophrenia with most suffers having a negative prognosis. Research in Brazil has demonstrated that many cases of mental illness can be linked to social environment factors such as living and work place settings, although other environmental factors like heavy metal poisoning cannot be ruled out as a key contributor [10]. This type of concern in urban environments demonstrates the need for green spaces to both improve the environment as well as provide a social space that can provide stress and anxiety relief to construct a healthy urban community. The Khoo Teck Puat Hospital [11] is an example of the fusion between greenery and the built environment having positive environmental effects and also beneficial to patient recovery (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Khoo Teck Puat Hospital showcasing a hospital in a garden and a garden inside a hospital. (Source: Khoo Teck Puat Hospital. Image by Alexandria Health).

Conclusion

Human relationships with green urban environments are incredibly complex, while many examples of green architecture create biodiversity, save electricity and water there is little research on how the spaces are used. Gil Penalosa who is an advocate for more active cities and director of Canadian organization 8-80 Cities says: “Successful public places around the world are successful not just because of the design but also because of the management. That’s not just cutting the grass and picking up the garbage. The bigger part of management is how to involve the community in the parks. We need to think of parks more as outdoor community centres where we need to invest in uses and activities so they can fulfil their potential. When we improve parks, we’re really improving quality of life” [14]. Studying Macquarie University through observation and discourse analysis as well as examples of green architecture across the world has demonstrated the positive environmental impacts but there are barriers to humans fully engaging with green spaces. Some of these issues may stem from the purpose of each example of green architecture and future studies would benefit from investigating a wider range of urban green spaces to gather a larger data pool. However, the lack of engagement with green spaces at Macquarie University could be countered through the University promoting the spaces by holding discussions or activities such as meditation or yoga in these spaces. Despite the many benefits that come with living in an urban environment such as internet, electricity and employment opportunities there are many physical and mental concerns that come from living in urban spaces. Fully utilizing green spaces is one way that humans can overcome the negative aspects of urban living [15]. Overcoming these concerns will be even more important in the future as urban populations continue to expand.

References

- Lovbrand E, Beck S, Chilvers J, Forsyth T, Hedren J, et al. (2014) Who speaks for the future of Earth? How critical social science can extend the conversation on the Anthropocene. Global Environmental Change 32: 211-218.

- Davis M (2004) Planet of Slums. Verso, London.

- Laland K, O’Brien M (2011) Cultural Niche Construction: An Introduction. Springer 6(3): 191-202.

- Macquarie University (2015) Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

- Zhoa D, He J, Johnson C, Mou B (2015) Social problems of green buildings: From the humanistic needs to social acceptance. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 51: 1594-1609.

- May T (1997) Participant Observation: Perspectives and Practice. In Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process, 2nd Buckingham, Philadelphia, pp.132-155.

- Fairclough N (1995) Critical Discourse Analysis. London, Longman.

- The Guardian (2014) The Guardian, Australia.

- Bond S (2011) Barriers and drivers to green buildings in Australia and New Zealan. Journal of Property Investment and Finance 29(4): 494-509.

- Mariana R, Andrea F Mello, Victor Fossaluza, Luciana P Nobrega, et al. (2012) Children working on the streets in Brazil: Predictors of mental health problems. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 22(3): 165-175.

- Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (2016) Alexandra Health, Singapore.

- Plumwood V (2009) Nature in the Active Voice. Australian Humanities Review 46: 113-129.

- Lang N (2013) Cultural and Social Elements in the Development of Green Architecture in Vietnam. Social and Behavioural Sciences 85: 16-26.

- Healthy Parks Healthy People Central (2016) HPHP Central, Victoria, Australia.

- Chauhan A, Johnson S (2003) Air pollution and infection in respiratory illness. Oxford Journals 68(1): 95-112.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...