Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1403

Review Article(ISSN: 2644-1403)

Strategies to Deliver Urology Services in the Times of COVID-19 Pandemic Based on Current Literature Volume 3 - Issue 4

Shiv Charan Navriya1, Satish Kumar Ranjan2*, Sunil Kumar1, Ashwani Kumar Kandari1, Tushar Aditya Narain1 and Kim Jacob Mammen3

- 1Assistant professor, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

- 2Senior Resident, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

- 3Professor, Urology, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Received: July 04, 2020; Published: August 25, 2020

Corresponding author: Satish Kumar RanjanSenior Resident, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh (AIIMS), India

DOI: 10.32474/GJAPM.2020.03.000168

Abstract

COVID-19 disease was first reported in Wuhan city of China, since then this is spreading with alarming speed and had already affected more than 213 countries around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a global impact on all sectors of public health and hospital services. Naturally, urology services have been affected too with several patients, suffering from urological malignancies and renal stone disease, left to their fate. Present records hint towards this pandemic continuing at least till the end of this year and it is only prudent that we come up with strategies to re-initiate urological services in a phased and a safe manner to tackle both, the urological diseases and the COVID-19 infection. This review aims at providing recommendations for resumption of urological services in a phased manner, based on the available evidences in literature.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic; Urological services; Resumption, Strategies

Introduction

The Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by Severe

Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was

first reported in Wuhan City, Hubei Province in China on the

31st December 2019. With the concern of the alarming spread of

infection and severity of disease, World Health Organization (WHO)

declared COVID-19 as a Public Health Emergency of International

Concern (PHEIC) on 30th January and as a pandemic on 11th

March 2020 [1]. This pandemic has already affected more than

213 countries around the world, with an approximate burden of

8.40 million cases and 0.45 million deaths. The United States of

America (USA), Russia, Spain, United Kingdom (UK), Italy, France

and Germany have been the worst affected countries despite

having a world-class health care system, with the USA heading

the list with 1.5 million cases and more than 93 thousand death

[2] Although affected countries have been in a state of complete

lockdown for many weeks, no measures stopped the spread of this

virus, and transmission reached at a stage of community-level and

have resulted in havoc on healthcare system [3]. The COVID-19

pandemic has had a global impact on all sectors of public health and

hospital services. Naturally, urology services have been affected too

with several patients, suffering from urological malignancies and

renal stone disease, left to their fate. Present records hint towards

this pandemic continuing at least till the end of this year and it is

only prudent that we come up with policies to re-initiate urological

services in a phased and a safe manner to tackle both, the urological

diseases and the COVID-19 infection.

A risk-benefit assessment for each patient requiring a urological

intervention should be done during this COVID-19 pandemic based

on the nature of the disease (benign vs malignant), risk of disease

progression, impact on life if left untreated, postponed or managed

medically and the risk of viral illness and transmission. Taking clues

from the previous pandemic, COVID-19 too may continue for years, and we cannot afford to leave our patients untreated all this while.

This review aims at providing recommendations for resumption

of urological services in a phased manner, based on the available

evidences in literature.

General Measures [4]

Every patient visiting the hospital should undergo a general symptomatic screening for COVID-19, including history of travel, before referring to a specialty clinic. At this stage, health care workers must have a N95/triple layer surgical mask and must use disposable gloves for the examination of the patients considering the potential source of infection from an asymptomatic case. Hospitals can be divided into COVID and Non- COVIDs block and all patients who require admission to the hospital can be admitted in COVID block in different rooms/areas and shifted to the Non-COVID area, once COVID-19 test report comes negative. Manpower should be divided into three pools and at a time, only one team should be working keeping others in reserve to minimize exposure. Specific testing of COVID-19 by Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) should be done in all patients who are symptomatic, have a contact history, require admission in the hospital or are planned for a surgical intervention and may be done in all old age patients with multiple comorbidities, because of high mortality in this group of patients [5]. The various Royal Colleges of United Kingdom jointly issued a statement, the “Intercollegiate General Surgery Guidance on COVID-19”. Adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and N95 Mask for the surgical team is essential to protect healthcare workers and ensure an adequate workforce available to treat patients. A negative pressure room is strongly recommended for intubation/extubating with an experienced anesthesiologist to minimize exposure in a COVID-19 suspected or proven case. All standard precautions should be maintained in the operating room (OR), including minimal personnel to be present inside the OR, mandatory PPE to be worn by all, even if the patient is negative for the COVID-19 test. If possible, a dedicated OR should be available with a trained team of healthcare workers including experienced surgeons, anesthesiologists, OR technicians, nursing officers, and ground staff. A complete record of manpower used in different areas should be maintained [4].

Adaptations to dance with COVID-19 Pandemic

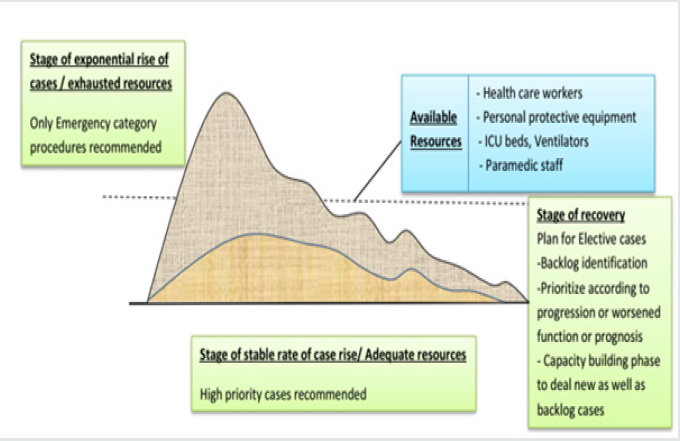

The usual urological diseases did not cease to cause morbidity and mortality while the SARS-CoV-2 virus was creating havoc worldwide. Urological malignancies and chronic kidney diseases continued to kill all this while. We need to strike a balance between providing urological services and conserving resources to face the biggest menace of all times. In order to combat increasing number of COVID-19 cases, reallocation of resources with redistribution of health care workers is the need of the hour as there will be an ever increasing demand for beds and ventilators.6 The decision to go ahead with a particular surgery should be based on meticulous risk-benefit analysis, considering the available healthcare resources and the deleterious effects of delaying a particular surgery [6] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Showing key considerations and risk-benefit analysis before starting elective surgery [8,9].

Strict adherence to COVID-19 safety guidelines, social distancing, entrance screening, waiting room policy, a visitor’s policy and separate staff to treat non-COVID19 patients are required. Considering the reported increased incidence of postoperative morbidity and mortality, it is advised to get pre-operative COVID-19 screening test in all patients and a mandate for patients with clinical symptoms or close contacts of COVID-19 patient or belonging to a hotspot area. Further decision of scheduling a case for surgery should be based on a prioritization strategy prepared for that institute. Time to time review of COVID-19 metrics and statics in local area are required frequently to reassess and reconsider a change in policy. Any plan in this crisis should be dynamic and should change as the situation unfolds [7-9].

Encouraging Telemedicine Services

Although the initial thoughts behind promoting telemedicine services were to provide health services to remote rural and sequestered areas [10], but this pandemic has unearthed the undiscovered potentials of distant telemedicine services and virtual OPDs. Telemedicine can be accessible anywhere and avoids a hospital visit, thus keeping both patient and health care providers safe. The ways of communication in telemedicine can be text message, voice calls or audio-video using social media platforms, telephonic calls or special telehealth applications [11] The discipline of urology has immense potential of using telemedicine services by providing prescription to non-operative patients, to triage a patient for hospital visit, for preoperative assessment and to follow-up in post-operative period allowing them to stay away from the hospital environment [12]

Triage and Prioritization Of Urology Services According to Slope Of Curve

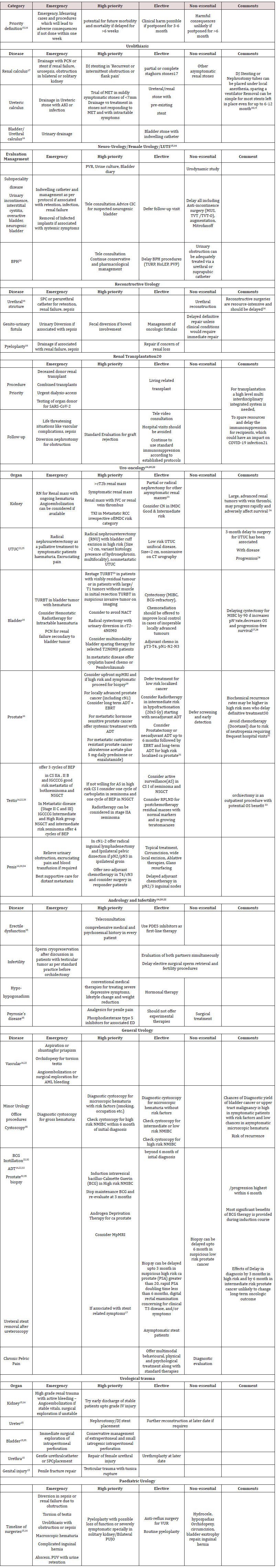

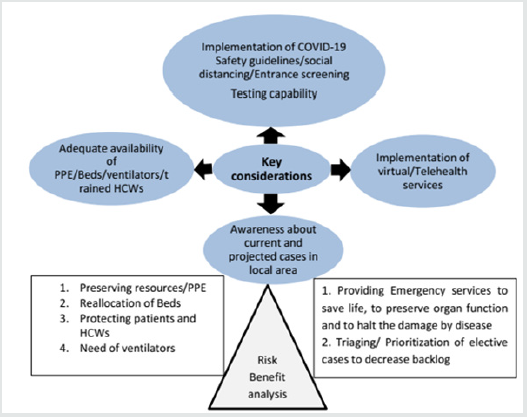

The rationale for prioritization is to provide surgical care timely to needy patient while preserving resources including PPE, beds, ventilators and sparing health care workers to provide alternate services related to COVID-19 pandemic [6] Determining which urology procedures can be safely delayed, should be based on the severity of disease, risk from delaying surgery, probable length of hospital stay, local healthcare resources and COVID-19 statics in that particular geographical region [13] Approaches to urological conditions should be tailored to individual settings, and preferably should have a shared decision making of both patient and treating urologist. Ample evidences are available in literature to guide us regarding the effects of delay of the particular procedure. Compiling these available evidences, we have tried to simplify the recommendations, pertinent to a given area with its burden of the COVID-19 disease. (Table 1) The first scenario is a state of exponential rise of COVID-19 cases and exhausted health care resources; in such a situation, only emergency lifesaving procedures should be performed. Second scenario includes availability of adequate health resources and stable rate of rise in COVID-19 cases; high priority cases can be catered to besides the emergency surgeries. Third scenario is a stage of decline of cases and re-established supply chain of resources; this is a phase of capacity building and backlog of cases should be identified and elective cases should be resumed. [14,15] (Figure 2).

Perioperative Adaptations

All the health care workers must have graded step wise training

of donning and doffing [16-18] The personal protection kit must

be government [19-34]authorized and shall be pre-available in OR

(operating rooms) [35]. Powered air purifying respirators if possible,

should be made available with PPE kits. A detailed surveillance

must be done of all the OR staff followed by a simulation course

incorporating all the precautionary steps relating to COVID-19 [37]

Staff should be divided into teams and the team members should

not come in contact with members of the other. All surgeries should

be performed by experienced surgeon with established standard

techniques. Senior surgeons above 60 years may play the role of

coordinators and make way for their younger colleagues as senior

citizens have been most susceptible for the disease [36].

OTs must be divided into COVID and non COVID OTs. All

precautions must be taken to keep COVID OT away from regular

elective OTs as far as possible. There are plenty of reports in

literature suggesting risk of infection by evaporated smoke during

surgery so attempts should be made to minimize the smoke

and aerosol generation. Electro cautery devices should be used

minimum and minimal invasive surgery with laparoscopy and

robotics should have minimum intra-abdominal pressure with

closed evacuation system for gas [37,38]. The US center for disease

control and prevention recommends a negative pressure airborne

infection isolation room for patients undergoing aerosol generating

procedures. All the OTs must remain closed for 10 minutes before

intubation and after extubating. There shall be minimum and

restricted movement from the OR. Prior to a surgery all necessary

items must be brought to OR. The main anaesthesia trolley should

remain outside the OR with minimum drugs to be prepared and

taken into OR. The drugs taken inside the OR room must be preprepared

into disposable syringes and labelled. In case of difficult

airway video-laryngoscope may be used with disposable blades

because it becomes difficult to intubate a patient with impaired

vision due to PPE/goggles [37]

Conclusion

Current statics predicts a long war with COVID-19, and it would be wise to resume routine urological services in a prioritized graded manner to avoid accumulation of large number of cases requiring intervention. Timely and appropriate urological care should be made available while at the same time, resources and manpower should be conserved so as to be in a position to fight both, the urological diseases and the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and emerge triumphant.

References

- WHO 2020 WHO Timeline- COVID-19.

- Worldometer 2020 COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.

- Government of India COVID-19 tracker.

- RCSE (2020) Intercollegiate General Surgery guidance on COVID -19 Update.

- Gupta N, Agrawal H (2020) COVID 19 and laparoscopic surgeons, the Indian scenario -Perspective. International Journal of Surgery 79: 165-167.

- Lodha R, Kabra SK (2020) COVID-19: How to Prepare for the Pandemic? Indian J Pediatr 87(6): 405-408.

- https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/437469/TG2 CreatingSurgeAcuteICUcapacity-eng.pdf.

- https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/resuming-elective-surgery.

- https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/roadmap-elective-surgery.

- Ellimoottil C, Skolarus T, Gettman M, Richard B, Alexander K, et al. (2016) Telemedicine in urology: state of the art. Urology 94: 10-16.

- Boehm K, Ziewers S, Brandt MP, Peter Sparwasser, Maximilian Haac, et al. (2020) Telemedicine Online Visits in Urology During the COVID-19 Pandemic-Potential, Risk Factors, and Patients' Perspective. Eur Urol S0302-2838(20): 30323-30327.

- Gadzinski AJ, Ellimoottil C (2020) Telehealth in urology after the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Urol : 1-2.

- https://www.facs.org/about-acs/covid-19/information-for-surgeons.

- Soreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, Schnitzbauer AA, Line PD, et al. (2020) Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg.

- Ribal MJ, Cornford P, Briganti A, Knoll T, Gravas S, et al. (2020) European Association of Urology Guidelines Office Rapid Reaction Group: An Organization-Wide Collaborative Effort to Adapt the European Association of Urology Guidelines Recommendations to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Era. Eur Urol.

- Heldwein FL, Loeb S, Wroclawski ML (2020) A systematic review on guidelines and recommendations for urology standard of care during COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol Focus.

- Metzler IS, Sorensen MD, Sweet RM, Harper JD (2020) Stone care triage during COVID-19 at the University of Washington. J Endourol 34: 539-540.

- Nourparvar P, Leung A, Shrewsberry AB (2016) Safety and efficacy of ureteral stent placement at the bedside using local anesthesia. J Urol 195: 1886-1890.

- Polat H, Yücel MÖ, Utangaç MM (2017) Management of forgotten ureteral stents: relationship between indwelling time and required treatment approaches. Balkan Med J 34: 301-307.

- Stensland KD, Morgan TM, Moinzadeh A (2020) Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol.

- https://tts.org/23-tid/tid-news/657-tid-update-and-guidance-on-2019-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-for-transplant-id-clinicians.

- Desouky E (2020) Urology in the Era of COVID-19: Mass Casualty Triage. Urol Pract.

- Mano R, Vertosick EA, Hakimi AA, Sternberg IA, Sjoberg DD, et al. (2016) The effect of delaying nephrectomy on oncologic outcomes in patients with renal tumors greater than 4 cm. Urol Oncol 34: 239.e1-8.

- Froehner M, Heberling U, Zastrow S, Toma M, Wirth MP (2016) Growth of a level III vena cava tumor thrombus within 1 month. Urology 90: e1-2.

- Bourgade V, Drouin SJ, Yates DR (2014) Impact of the length of time between diagnosis and surgical removal of urologic neoplasms on survival. World J Urol 32: 475-479.

- Zehnder P, Thalmann GN (2013) Timing and outcomes for radical cystectomy in no muscle invasive bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol 23: 423-428.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, et al. (2020) Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 21: 335-337.

- Fahmy NM, Mahmud S, Aprikian AG (2006) Delay in the surgical treatment of bladder cancer and survival: Systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol 50: 1176-1182.

- Ahmed HU, Bosaily AE, Brown LC, Gabe R, Kaplan R, et al. (2017) Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): A paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet 389: 815-822.

- Fossati N, Rossi MS, Cucchiara V, Gandaglia G, Dell’Oglio P, et al. (2017) Evaluating the effect of time from prostate cancer diagnosis to radical prostatectomy on cancer control: Can surgery be postponed safely? Urol Oncol 35: 150(e9-e15).

- Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Robinson D (2016) Immediate versus delayed prostatectomy: Nationwide population-based study. Scand J Urol 50: 246-254.

- Huyghe E, Muller A, Mieusset R (2007) Impact of diagnostic delay in testis cancer: results of a large population-based study. Eur Urol 52: 1710-1716.

- Gao W, Song LB, Yang J, Song NH, Wu XF, et al. (2016) Risk factors and negative consequences of patient’s delay for penile carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 14: 124.

- Howard B, Goldman George PH (2020) Recommendations for Tiered Stratification of Urological Surgery Urgency in the COVID-19 Era. J Urol 204: 11-13.

- Vijayakumar V (2020) Personal Protection Prior to Preoperative Assessment-Little more an anaesthesiologist can do to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission and COVID-19 infection. Ain- shams journal of anaesthesiology 12(1): 13-15.

- Coccolini F, Perrone G, Chiarugi M (2020) Surgery in COVID-19 patients: operational directives. World J Emerg Surg 15(1): 25.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, Song KJ (2016) Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med 73: 857-863.

- Li CI, Pai JY, Chen CH (2020) Characterization of smoke generated during the use of surgical knife in laparotomy surgeries. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 70: 324-332.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...