Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1403

Research Article(ISSN: 2644-1403)

Peritoneal Irrigation of Fentanyl Added to LevoBupivacaine Versus Patient Controlled Intravenous Analgesia (PCIA) in Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Cancer Surgeries Volume 1 - Issue 3

Alaa Ali M Elzohry1*, Ahmed Fetouh Abdelrahman2, Ali Taha Abdel Wahab3, Wegdan A Ali3 and Mohamed Abd El moniem Bakr4

- 1South Egypt Cancer Institute, Assiut University, Egypt

- 2Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Egypt

- 3Faculty of Medicine, Minia University, Egypt

- 4Faculty of medicine, Assiut University, Egypt

Received:May 20, 2019; Published: May 24, 2019

Corresponding author:Alaa Ali M Elzohry, Department of Anesthesia, ICU and Pain Relief, South Egypt Cancer Institute, Assiut University, Arab Republic of Egypt

DOI: 10.32474/GJAPM.2019.01.000113

Abstract

Background: Major abdominal surgeries still the main line of treatment for upper abdominal malignancies and these surgeries induce severe postoperative pain with different types either somatic or visceral. If such pain not controlled, may cause various organ dysfunctions and prolong both hospital and ICU stay. So, an appropriate pain therapy to those patients with least complications must be applicated.

Objective: To compare analgesic efficacy of intraperitoneal irrigation of fentanyl added to levo-bupivacaine versus patient controlled intravenous analgesia in patients undergoing major abdominal cancer surgeries.

Methods: 120 patients (ASA II-III) of either sex were scheduled for elective upper abdominal cancer surgeries. Patients were randomly allocated into three groups (40 patients each), to receive: post-operative PCA fentanyl through IV rout (group I), intraperitoneal irrigation of Levo-bupivacaine 25% in 50 ml volume (group II), or intraperitoneal irrigation of Levo-bupivacaine 25% plus fentanyl 200 mic in 50 ml volume (group III). Postoperative pain was assessed over 48 h using Numerical rating scale (NRS). The intra and post-operative haemodynamics, sedation score and overall post-operative patient fentanyl consumption were recorded. Any concomitant events like nausea; vomiting, pruritus or respiratory complications were recorded postoperatively.

Keywords: Intraperitoneal irrigation; Major upper abdominal cancer surgeries; Postoperative pain; NRS scale; Fentanyl; Levo bupivacaine

Introduction

Surgical interventions still the main line of treatment for upper abdominal malignancies, and according to recent statics, millions of surgical interventions were performed every year. These surgeries are classified as high-risk patients [1]. Major surgeries carried out in upper abdomen -like these selected for the study- are usually associated with intense pain that, if not properly treated, may cause deep physiological and hormonal alterations in the body .Some of the main complications of untreated postoperative pain are cardiocirculatory and respiratory complications [2,3]. So effective postoperative pain control has many benefits such as; encourages early ambulation, reducing the risk of thrombosis, decreases cardiopulmonary complications and increases health-related quality of life [4]. Opioids analgesics used to be considered the gold standard analgesic for major surgery, but unfortunately, intravenous opioids administration have many side effects, as nausea and vomiting, pruritus, gastrointestinal symptoms and respiratory depression [5].

Neuro-axial blocks as (TEA) are recently used as a good postoperative analgesic strategy because it is very effective but still invasive method and relatively needs experience [6-7]. Local anesthetic (LA) drugs are well recognized and represent one of the most important classes of drug in perioperative care. Local anesthetic agents do not have the adverse effects of systemically administered opioids and act directly on the tissue to which they are applied on as peritoneal cavity [8]. PCA if used intravenously carries many advantages over conventional pain management because the therapy is individualized to the patient and patients are the best to assess their pain and they can get medication as and when required by pressing a button of PCA pump. Thus, it reduces overdose and also reduces nursing aid [9]. The aim of this study was to compare analgesic efficacy of intraperitoneal irrigation of fentanyl added to levo-bupivacaine with patient controlled intravenous analgesia in patients undergoing major abdominal cancer surgeries.

Patients and Methods

This study was designed as a prospective randomized clinical trial after approval of local ethics committee of the South Egypt Cancer Institute, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt. One hundred twenty patients (ASA II-III) were scheduled for elective major abdominal cancer surgery from June 2018 till March 2018 and after written informed consent from every patient. Exclusion criteria were as following: allergy to local anesthetic solutions or opioids and patient whose ability to use PCA pump or who cannot be taught how to evaluate their own pain intensity. One day before surgery, preoperative data were collected as; demographic data, medical history, physical examination and routine laboratory investigations. The night before surgery, all patients were taught how to evaluate their own pain intensity using the Numerical rating Scale (NRS), scored from 0-10 (where 0= no pain and 10=worst pain imaginable).and how to use the PCA device (Abbott Pain Management Provider. S. No: 96450292. Abbott Laboratory, North Chicago. IL: 60064, USA)®. All patients were randomly assigned into three groups (40 patients each) by using opaque sealed envelopes containing computer generated randomization schedule, the opaque sealed envelopes are sequentially numbered that were open before application of anesthetic plan. Patients of all groups were premedicated with intravenous midazolam 0.05mg/ kg and ranitidine 50mg. After shifting the patient to the induction room, ECG, pulse oximeter, non-invasive blood pressure monitors were attached. Peripheral venous line and subclavian vein catheter were established, and an infusion of lactated ringers’ solution was started.

a) Group I (No=40): Surgery was performed under standard general anesthesia with intra-operative analgesia by continuous intravenous fentanyl infusion.

b) Group II (No=40): Surgery was performed under standard general anesthesia with intraoperative irrigation of Levo-bupivacaine 25% in 50ml volume just before peritoneal closure after good surgical heamostasis.

c) Group III (No=40): Surgery was performed under standard general anesthesia and additionally intraperitoneal irrigation of Levo-bupivacaine 25% plus fentanyl 200mic in 50ml volume just before peritoneal closure after good surgical heamostasis. All patients received intra operative ketorolac 30mg, Paracetamol 1gm and, fentanyl was given for rescue analgesia which was adjusted as following; 1mic / kg. The analgesic regimen was adjusted to achieve a stable MAP and HR within 10% of baseline.

Standard General Anesthesia

After pre-oxygenation for 3 minutes, intravenous anesthesia (propofol 1.5mg/kg) induced with fentanyl 1-2μg/kg administered over min. Tracheal intubation was performed after adequate neuromuscular blockade with cisatracurium 0.5mg/kg. Anesthesia was maintained by sevoflurane 1-1.5 MAC, cisatracurium 0.03mg/ kg given when indicated. Patients were mechanically ventilated to maintain ETCO2 between 35-40mmHg. The inspired oxygen fraction (FIO2) was 0.5 using oxygen-and-air mixtures. At the end of surgery neuromuscular block was antagonized in all patients with neostigmine 0.05mg/kg and atropine 0.02mg/kg and trachea was extubated in the operating room. Tracheal extubation will be performed when patients meet the following criteria: hemodynamic stability, adequate muscle strength, full consciousness, and adequate ventilation breathing rate: 10 to 30 breaths/min, PaO2 / IFO2 ≥80/0.4, PaCO2 , 30 to 45mmHg). Intra operative data such as HR, MAP, and operative duration were recorded for analysis. At the end of surgery, abdominal drains were closed by clamp for 30 minutes in groups II and III.

Post-operative, all patients were admitted for 48 hours to surgical ICU to received post-operative ketorolac 30mg/12 hours, Paracetamol 1gm/8 hours and, fentanyl was given for rescue analgesia via PCA which was adjusted as following; 20 mic with lockout interval of 15 min with no background infusion. The analgesic regimen was adjusted to achieve a NRS scores less than 3. The following were recorded

a) HR, MAP and were recorded everyone hour in ICU.

b) NRS- every 4 hours for 2 days-for pain measurement. And total fentanyl consumption was calculated.

c) Sedation was assessed one day postoperatively by 5 points Sedation score (at the same time intervals of NRS) as follows 0 = aware - 1 = drowsy - 2 = asleep/easily respond to verbal command - 3 = asleep/difficulty responding to verbal command -4 = asleep/no respond to verbal command.

d) Any concomitant events like nausea; vomiting, pruritus or respiratory depression (decrease oxygen saturation ≥90%) were recorded postoperatively

Statistical Analysis

The required sample size was calculated using Epi Info software version 7 (CDC, 2012)®. Using post hoc power analysis with accuracy mode calculations with NRS as the primary objective and therefore, it was estimated that minimum sample size of 39 patients in each study group would a chive a power of 80% to detect an effect size of 0.8 in the outcome measures of interest, assuming a type I error of 0.05. All analyses were performed with the SPSS 21.0® software. Categorical variables were described by number and percent (N, %), where continuous variables described by mean and standard deviation (Mean, SD). And Mann–Whitney test were used to compare between two groups while Chi square test was used for qualitative data. Where compare between continuous variables by t-test. P was considered significant if 60.05 at confidence interval 95%.

Results

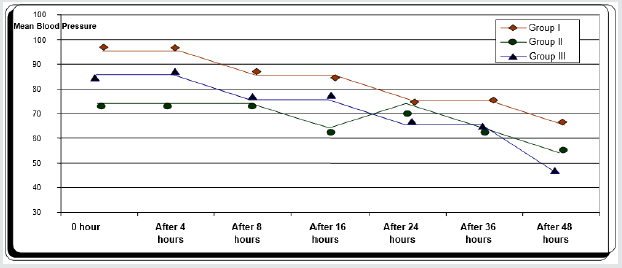

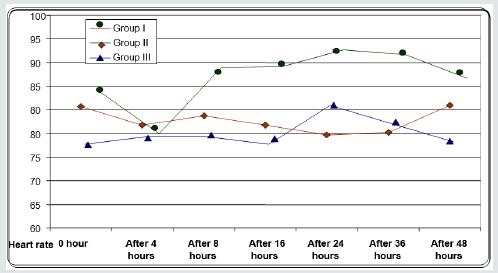

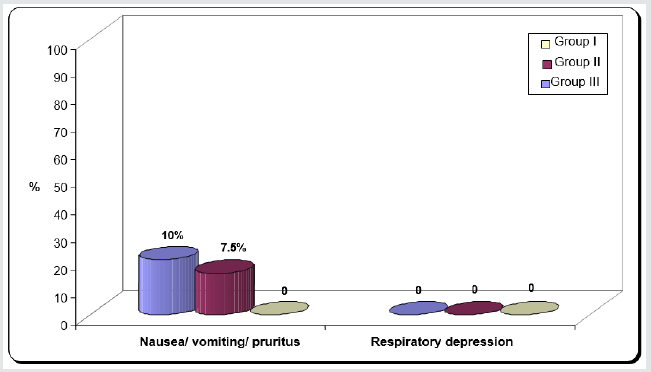

Regarding demographic data there was no between all three groups (Table 1-3). There was a significant decrease in pain sensation in all groups during first day postoperative in group II and much more in group III (P. value 0.000*) (Table 4) and postoperative analgesic consumption much more decreased in group III in comparison to other groups (P. value 0.000*) (Table 5). Patient haemodynamics either intra or post-operative were significantly optimized in groups II-III Tables 2 & 3) (Figure 1 & 2) (P. value 0.002*). As regard side effects (Figure 3) sedation scale, patients of the I group were significantly more sedated than other two groups at immediate postoperative only (Table 6) (P. value 0.0.001*).

ASA: American society of anesthesiologists

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and Number, percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups no significance regarding patient’s characteristics.

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups no significance regarding MAP.

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

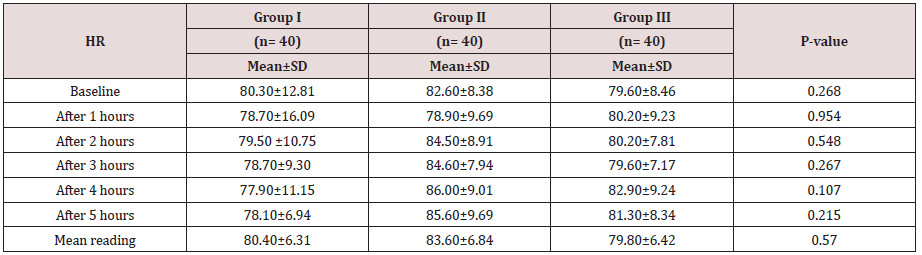

Between three groups no significance regarding MAP.

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

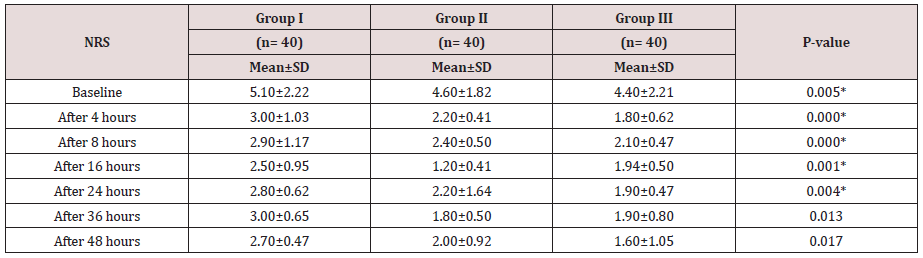

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups there was significant difference regarding VAS scores being decreased in group II- and much more decreased in group III in comparison to group I (P value 0.000*).

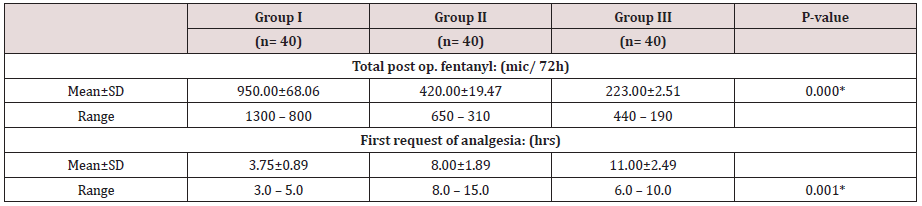

Data expressed as (Mean ± SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups there was significant difference regarding post-operative morphine consumption decreased in group II- and much more decreased in group III in comparison to group I (P value 0.000*)

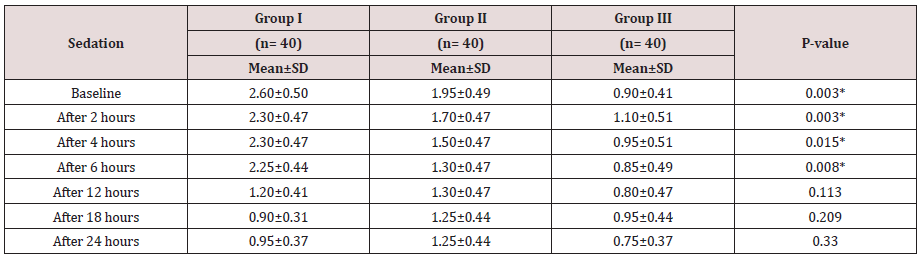

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups there was significant difference regarding sedation scores that increased in group I in comparison to other two groups. (P value 0.000*)

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups there was significant difference regarding post-operative MAP being decreased in early post-operative period in group II and III (P value 0.002*).

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups there was significant difference regarding post operative HR being decreased in early post-operative period in group II and III (P value 0.001*).

Data expressed as (Mean±SD) and number / percentage (%).

P. value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Between three groups there was significant difference regarding side effects that noticed in group III mainly. (P value 0.005*).

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial, we compared intraperitoneal irrigation of local anesthetic agent levo-bupivacaine group (II) and with opioid agent fentanyl (III) versus IV PCA to reduce pain after major abdominal cancer surgeries. The results were decreased postoperative pain scores in all groups but more in group III and this reflected on decrease opioids consumption post operatively. A lot of authors find that postoperative pain is inadequately treated in approximately one half of all surgical procedures [9]. And all clinical trials confirm that a high-quality postoperative pain management improves recovery and also reduces the risk of postoperative acute adverse effects such as pulmonary dysfunction and chronic adverse effect as (delayed recovery, hospital discharge and chronic pain) [10]. Therefore, a multimodal approach, using local anesthetics with other drugs as opioids may help to improving the quality of analgesia, recovery and reduce opioid dose requirement and side effects [11]. A lot of previous clinical trial studied intraperitoneal LA as a methods of analgesic administration to control pain following different abdominal surgeries, for example Choi et al. [12] who concluded in their meta-analysis that intraperitoneal LA in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) exhibited beneficial effects on post-operative abdominal, visceral, and shoulder pain in a resting state. Also, intraperitoneal LA has previously been shown to be of benefit in patients undergoing open hysterectomy [13], laparoscopic gynecological procedures [14], and laparoscopic cholecystectomy [15]. Also, Bucciero et al. [16] who found that intraperitoneal Ropivacaine was associated with reduced shoulder pain and unassisted walking after LC. Incisional component of pain in abdominal surgeries is the predominant component [17]. A LA used at this site effectively relieves pain [18]. Currently, there is no clear-cut consensus as to what the best mode of its use is. However, our usage of levo-bupivacaine in peritoneal irrigation yielded excellent results in terms of significantly reduced pain and requirement of post-operative analgesics in all groups [19]. We chose levo-bupivacaine in our study because of its better pharmacokinetic and less toxic profiles especially cardiac toxicity [20,21]. However, few clinical trials have compared between LAs in terms of their practical potency as Papagiannopoulou et al. [22] who compared the analgesic efficacy of ropivacaine and levo-bupivacaine, and concluded that local tissue infiltration with levobupivacaine was more effective than ropivacaine in reducing the post-operative pain associated with abdominal surgeries. The intraperitoneal route of administration of local anesthetic (LA) is simple, does not involve additional central neuroaxial block and is suited to the practice of ambulatory anesthesia [23]. We can explain the analgesic effects of intraperitoneal Las; LAs block visceral afferent signaling, and potentially modify visceral nociception by blocking sodium channels [24]. Ahn et al. [25] who reported that, use of intraperitoneal LA i.e., at the time induction of anesthesia was better than its use at the end of procedure. As regard Postoperative nausea, vomiting and respiratory depression, were comparable in all groups but sedation in patients of the group III were significantly more sedated than other two groups at immediate postoperative time but no significant differences between both groups after that. The total dose of post-operative fentanyl was significantly lower in group III in comparison to other two groups.

We can get benefits from application of opioids with LAs to have synergism in efficacy because opioids can inhibit pain transmission from afferent nerves to the central nervous system through interaction with pre- and postsynaptic opioid receptors in the peripheral nerves [26]. Confirming our point of view regarding concept of synergism, a study of patients undergoing thoracic surgery, despite the infusion of bupivacaine alone via a thoracic epidural, 30%of patient’s required opioid supplementation for inadequate analgesia and 80% had significant hypotension [27]. PCA in this study was used intravenously with the following advantages over conventional pain management are that the therapy is individualized to the patient. Patients are the best to assess their pain and they can get medication as and when required by pressing a button of PCA pump. Thus, it reduces overdose and reduces nursing aid [28]. At the end of the 24h postoperatively there was no significant difference in NRS between all groups. Side effects like delayed respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting were caused by the presence of drug either in systemic circulation [29]. Comparing between opioids that was added either morphine or fentanyl, our choice was fentanyl, and this is based on the higher lipophilicity of fentanyl that makes it shorter duration of action, lower incidence of side effects, and reduced risk of respiratory depression [30].

Conclusion

This study concluded that intraperitoneal irrigation of Levobupivacaine in patients undergoing major abdominal cancer surgeries was safe and effective in pain relief and adding fentanyl in a dose of 200 mic increased the analgesic efficacy with comparable side effects when compared to IV PCA. We can consider intraperitoneal irrigation is a safe, easy and effective method for control of pain following major abdominal cancer surgeries when TEA or PCA is not applicable.

References

- Imani F (2011) Postoperative pain management Anesth Pain 1(1): 6-7

- (2012) Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 116: 248-273.

- Pogatzki Zahn E, Chandrasena C, Schug SA (2014) Nonopioid analgesics for postoperative pain management Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 27: 513- 519.

- Arbabi S, Shirmohammadi M, Ebrahim Soltani A, Ziaeefard M, Faiz SH, et al. (2013) The effect of caudal anesthesia with bupivacaine and its mixture with midazolam or ketamine on postoperative pain control in children. Anesthesiology and Pain Journal 3: 155-161.

- Cassuto J, Sinclair R, Bonderovic M (2006) Anti-inflammatory properties of local anesthetic and their present and potential clinical implications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 50: 256-282.

- Craft Jennifer (2010) Patient controlled analgesia: Is it worth the painful prescribing process? Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 23(4): 434-438.

- Kang JG, Kim MH, Kim EH, Lee SH (2012) Intra operative intravenous lidocaine reduces hospital length of stay following open gastrectomy for stomach cancer in men. J Clin Anest 24: 465-470.

- Wewers ME, Lowe NK (1990) A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Research in Nursing and Health13: 227-236.

- Marks JL, Ata B, Tulandi T (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetics for reduction of pain after gynecologic laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 19: 545-553.

- McDermott AM, Chang KH, Mieske K et al. (2015) Aerosolized intraperitoneal local anesthetic for laparoscopic surgery: a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Surg 39: 1681-1689.

- Gupta M, Naithani U, Singariya G, Gupta S (2016) Comparison of 0.25% ropivacaine for intraperitoneal instillation v/s rectus sheath block for postoperative pain relief following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study. J Clin Diagn Res 10: Uc10-U15.

- Choi GJ, Kang H, Baek CW, Jung YH, Kim DR (2015) Effect of intraperitoneal local anesthetic on pain characteristics after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Gastroenterol 21(47): 13386-13395.

- Chakravarty N, Singhai S, Shidhaye RV (2014) Evaluation of intraperitoneal bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a prospective randomized trial Anaesth Pain Intensive Care 18: 361-366.

- Cassuto J, Sinclair R, Bonderovic M (2006) Anti-inflammatory properties of local anesthetic and their present and potential clinical implications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 50: 256-282.

- Ingelmo PM, Bucciero M, Somaini M (2013) Intraperitoneal nebulization of ropivacaine for pain control after laparoscopic choelcystectomy: a doublé-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial Br J Anaesthesia 110: 800-806.

- Bucciero M, Ingelmo PM, Fumagalli R, Noll E, Garbagnati A (2011) Intraperitoneal ropivacaine nebulization for pain management after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparison with intraperitoneal instillation. Anesth Analg 113: 1266-1271.

- Khan MR, Raza R, Zafar SN, Shamim F, Raza SA, Pal KM, et al. (2012) Intraperitoneal lignocaine (lidocaine) versus bupivacaine after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Surgical Research 178: 662-669.

- Collins GG, Gadzinski JA, Fitzgeral GD (2015) Surgical pain control with ropivacaine by atomized delivery (spray): a randomized controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.

- Duchene DA, Anderson K, Cadeddu JA (2007) Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. In: Bishoff JT, Kavoussi LR (Eds.), Atlas of Laparoscopic Urologic Surgery. Saunders, Philadelphia, USA, p.70.

- Savaris RF, Chicar LL, Cristovam RS, Moraes GS, Miguel OA (2010) Does bupivacaine in laparoscopic ports reduce postsurgery pain in tubal ligation by electrocoagulation? A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 81: 542-546.

- Honca M, Kose EA, Bulus H, Horasanli E (2014) The postoperative analgesic efficacy of intraperitoneal bupivacaine compared with levobupivacaine in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Chir Belg 114: 174-178.

- Pappas Gogos G, Tsimogiannis KE, Zikos N (2008) Preincisional and intraperitoneal ropivacaine plus normal saline infusion for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic choelcystectomy: a randomized, doubleblind controlled trial. Surg Endosc 22: 2036- 2045.

- Roberts KJ, Gilmour J, Pande R, Nightingale P, Tan LC, et al. (2011) Efficacy of intraperitoneal local anaesthetic techniques during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 25: 3698-3705.

- Kahokehr A (2013) Intraperitoneal local anesthetic for postoperative pain. Saudi J Anaesth 7: 5.

- Yeh CN, Tsai CY, Cheng CT, Wang SY, Liu YY, et al. (2014) Pain relief from combined wound and intraperitoneal local anesthesia for patients who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMC Surg 14: 28.

- Conacher ID, Paes ML, Jacobson L, Phillips PD, Heaviside DW (1983) Epidural analgesia following thoracic surgery. A review of two years’ experience Anesthesia 38: 546-551.

- Ng A, Smith G (2002) Intraperitoneal administration of analgesia: is this practice of any utility? Br J Anaesth 89: 535-537.

- Williamson KM, Cotton BR, Smith G (1997) Intraperitoneal lignocaine for pain relief after total abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Anaesth 78: 675- 757.

- Teng YH, Hu JS, Tsai SK, Liew C, Lui PW (2004) Efficacy and adverse effects of patient-controlled epidural or intravenous analgesia after major surgery. Chang Gung Med J 27: 877-86.

- Bouman EA, Theunissen M, Bons SA, van Mook WN, Gramke HF, et al. (2013) Reduced incidence of chronic postsurgical pain after epidural analgesia for abdominal surgery. Pain Practice.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...