Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1403

Research Article(ISSN: 2644-1403)

Evaluation of Intraperitoneal and Port Site Administration of Bupivacaine for Postoperative Analgesia Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy : A Randomized Controlled Study. Volume 1 - Issue 5

Shilpashri A M1*, Rashmi C2 and Priya R3

- 1Professsor, Department of Anesthesiology, JJM Medical College, Davangere, India

- 2Senior Resident, Department of Anesthesiology, Navodaya Medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Raichur, India

- 3Junior Resident, Department of Anesthesiology, JJM Medical College, Davangere, India

Received: July 07, 2019; Published: July 12, 2019

Corresponding author: Shilpashri AM, Department of Anesthesiology, JJM Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka, India

DOI: 10.32474/GJAPM.2019.01.000124

Abstract

Background: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the procedure of choice for gall bladder removal. Post-operative pain management involves the use of opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], paracetamol and local anesthetics. Opioids may delay recovery and discharge from the hospital. NSAIDS cause gastric irritation in addition to impairing platelet and renal function. Instilling local anesthetic intra-peritoneally and through port sites is a non- invasive method to provide excellent analgesia in the immediate postoperative period. Bupivacaine is a long acting local anesthetic devoid of any serious side effects when given as local infiltration. Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of bupivacaine in reducing postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy when given intra-peritoneally and through port site infiltration. Materials and methods: 100 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy were divided into 2 equal groups. In Group B 50 patients received 20ml of 0.25% bupivacaine given intraperitoneally and another 10ml of same for port site infiltration. In Group A 50 patients received 0.9% Normal saline 20ml and 10ml respectively at the same sites. Postoperative pain need for rescue analgesics, vital parameters and adverse effects were monitored in the post- operative period. Results: Both the study groups were similar in terms of age structure and majority were female gender. Postoperative pain was significantly reduced in the bupivacaine group. Most of patients who received normal saline needed rescue analgesia immediately in the postoperative period compared to very few patients in group B. There were statistically significant changes in the postoperative vital signs in both the study groups. Conclusion: Intraperitoneal and periportal infiltration of 0.25% bupivacaine is a simple, cost effective and minimally invasive method that provides early analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy with no adverse effects and may become routine practice reducing the analgesic consumption in the immediate postoperative period.

Keywords: Ropivacaine; Bupivacaine; Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Intraperitoneal

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has displayed advantages over open surgery including lower morbidity and mortality, smaller incisions, reduced length of hospital stay faster recovery and earlier return to normal activities and work [1-3]. Technical advantages in the field of laparoscopic surgery such as the miniaturization of instruments, the use of gasless laparoscopy, and the use of more efficient lighting techniques, help to reduce surgical trauma and discomfort and thereby widen the scope of laparoscopy [4]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is commonly done to remove diseased gall bladder [5]. However, pain is not completely abolished after laparoscopy. Patients frequently describe sub-diaphragmatic and shoulder tip pain in addition to the discomfort of port site incisions [6-7]. Intraperitoneal insufflation of gas like carbon dioxide stretches the abdominal tissues, causes traumatic vessel tear, nerve traction and release of inflammatory mediators causing perioperative pain. Pain may be visceral or somatic, upper abdominal, lower abdominal or in shoulders as well [8-9]. Immediately after surgery, the intensity of pain is more in the first 24 hours and then decreases gradually [10]. Occurrence of pain could be due to multiple factors such as prolonged surgery, degree of invasiveness of the procedure, surgeon’s expertise, the amount of intraoperative bleeding, the size of the trocars, suction used to remove any blood and insufflated gas at the end of surgery [11-12]. Postoperative analgesia involves the use of opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol and local anesthetics. However, opioids delayed the recovery and discharge from hospital [13]. NSAIDs also have their disadvantages such as gastric irritation in addition to impairing platelet and renal function [14]. Local anesthetics are devoid of such adverse effects.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of bupivacaine in reducing postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy when given intra-peritoneally and through port site infiltration.

Materials and Methods

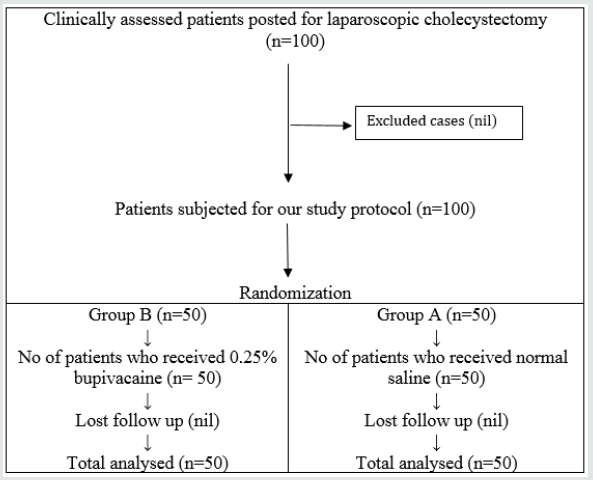

This clinical study included hundred adult patients of ASA physical status I & II in the age group of 20 to 70 years, either male or female, posted for Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Bapuji hospital attached to JJM Medical College, Davangere. After obtaining ethical committee approval from the institute and written informed consent from the patient, a placebo-controlled study was carried out on the patients. The patients were divided into two groups of fifty each. Group B patients received 20ml of 0.25% bupivacaine given intraperitoneally and another 10ml of same for port site infiltration. Group A patients received 0.9% Normal saline 20ml and 10ml respectively at the same sites. Clinically assessed patients posted for laparoscopic cholecystectomy [n=100] Patients subjected for our study protocol [n=100] (Figures 1-4).

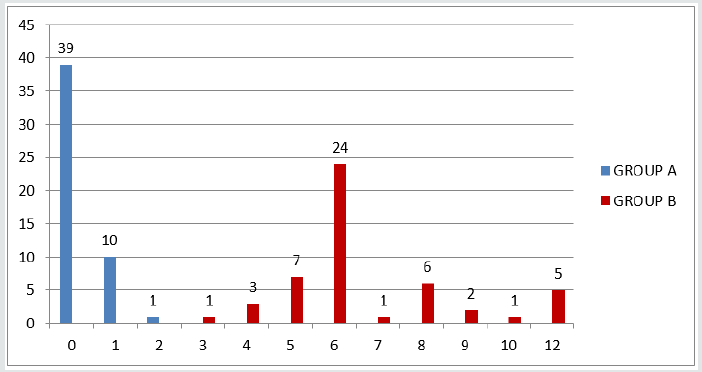

Figure 3: Bar Chart representing the distribution of subjects based on the time at which they received first rescue analgesic across the two treatment groups.

Inclusion criteria

a) Patients of age between 20-70 years.

b) Gender: both male and female.

c) Patients who fits into American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status criteria 1 and 2 scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

d) Patients who are willing and able to give informed written consent.

e) Concomitant medications: The patient can take relevant medication for concomitant diseases like diabetes, hypertension etc.

Exclusion criteria

a. Patient refusal.

b. Patients who do not understand the visual analogue score.

c. Patients who are allergic to bupivacaine. A thorough history, general physical and systemic examination, and airway assessment were done. Routine laboratory investigations like complete blood picture, renal function tests, bleeding and clotting time, HIV, HBs Ag status, ECG were done.

Technique

The patients were introduced to the visual analogue scale on the day previous to the surgery and a detailed explanation of the same was given. Patient was shifted to OT and intravenous access was secured. ECG, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximeter monitors were attached, and baseline parameters were recorded. Patient was premedicated with glycopyrrolate 0.02mg/ kg, midazolam 0.03mg/kg and pentazocine 0.5mg/kg prior to surgery. Patient was induced with propofol 2mg/kg, relaxed with a short acting muscle relaxant such as succinyl choline 2mg/kg, intubated and anesthesia was maintained oxygen and nitrous oxide, inhalational agent and vecuronium bromide 0.05mg/kg in both the groups. Intra operatively heart rate, BP, end tidal CO2 and oxygen saturation were monitored. After completion of surgery, the local anesthetic solution was sprayed over the gall bladder bed, the right sub diaphragmatic space and the under surface of the diaphragm. Port sites were also infiltrated. Group B patients received 20ml of 0.25% bupivacaine intraperitoneally and another 10ml of same for port site infiltration. Group A patients received 0.9% Normal saline 20ml and 10ml respectively at the same sites. Patients were reversed using neostigmine 0.05mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.02mg/kg at the end of surgery and extubated. In the postoperative room using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), pain was assessed at 0, 30 minutes, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours. Injection. diclofenac aqueous 75mg intravenous infusion in 100ml normal saline was given to all patients on demand. The total injection. diclofenac aqueous 75mg consumption in 24 hours were noted. The episodes of nausea, vomiting and the need of any rescue analgesics for pain if any were noted. The vital parameters were also assessed at the above times. All the collected data were evaluated, compared and analysed using SPSS software version 16. Numerical variables were entered as mean ±standard deviation (SD). Student ‘t’ test was applied for two-group comparison and paired ‘t’ test for intragroup comparison of hemodynamic variables. For categorical variables, ratios, proportions and percentages were used and compared with Fischer’s exact test. The p value of <0.05 was taken as statistically significant difference between the two groups.

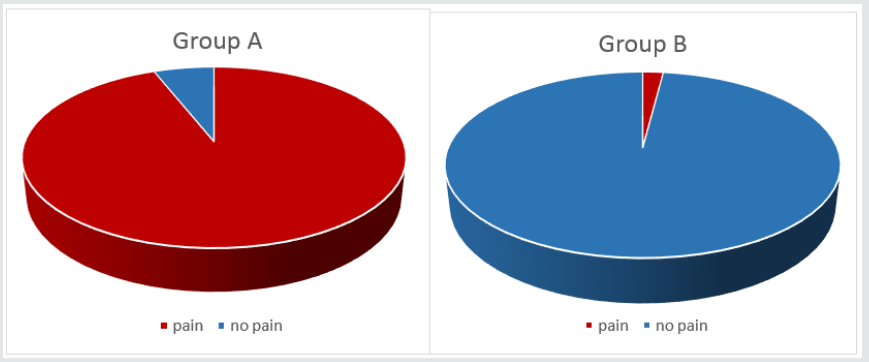

In both the study groups, we included 50 patients, majority of whom were of female gender, 31 in bupivacaine group and 28 in normal saline group. This could be due to the fact that the disease is more prevalent in females when compared to males. The significant changes were noted in the heart rate of patients in both the study groups after 30min, 1 hour,2 hours, 4 hours, 8hours and 12 hours, across the study period of 24 hours. Both the study groups were comparable in terms of mean systolic blood pressure changes. The statistically significant changes were noted after 30 mins, 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, 8 hours and 12 hours, 24 hours in the study groups. The statistically significant changes in diastolic BP were noted after 8-12 and 24 hours in the study groups. Changes in SP02 in any of the study groups across the time period were negligible. Group B’s mean VAS score was less than that of group A and was statistically significant at any given point of time in the study groups. The occurrence of post op nausea and vomiting in both the study groups were ascertained but was not statistically significant. Seven cases in group A and four cases in group B had post-operative nausea and vomiting. All the cases were assessed for the time at which first rescue analgesics were given. In group A, maximum number of patients received rescue analgesics in first two hours itself whereas in group B, rescue analgesics were needed at fourth to sixth hour. This explains that, intraperitoneal and peri portal administration of 0.25% of Bupivacaine will last for four to six hours. And group B received less number of rescue analgesics as compared to group A and it was statistically significant with p value < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study we evaluated the effectiveness of intra peritoneal instillation of 0.25% bupivacaine for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The pain after laparoscopic surgery is variable in duration, intensity and character. Tendency and preference of patients for laparoscopic surgery is more due to cosmetic scars, less hospital stay and less pain. But there is less importance in recognition and management of pain. The results of this study showed that intraperitoneal infiltration of 0.25% bupivacaine along with infiltration of port sites, decreased the pain in first 24 hours and there was less analgesic consumption as well.

In our study, majority were female gender, 31 in bupivacaine group and 28 in normal saline group. This indicates that the disease is more prevalent in females when compared to males. The mean VAS score in group B was less when compared to group A and was statistically significant at any given point of time. Neerja Bhardwaj et al [15] have studied intraperitoneal bupivacaine instillation for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and concluded that good pain relief was present on using bupivacaine. Sami Hasson et al [16] have studied postoperative pain reduction with bupivacaine instillation after laparoscopic cholecystectomy on 80 patients using 40ml of 0.125% bupivacaine diluted in 60ml of 0.9% isotonic saline and concluded the same. Similarly, Tsimoyiannis EC et al. [17] in their study found that postoperative pain was significantly reduced in the bupivacaine group. Narchi et al. [18] showed that intraperitoneal instillation of 100 mg of bupivacaine was a safe technique with zero toxicity and good pain relief in initial few hours. Pasqualucci A et al. [19] used 0.5% bupivacaine and noted the decrease in pain was due to a complete block of afferents. Chandigarh et al [20] noted that patient was pain free up to 2 hours post-surgery with the intraperitoneal administration of 0.25% bupivacaine. Alam MS et al. [21] showed that intraperitoneal and port site infiltration of bupivacaine is simple, inexpensive and effective technique to minimize early postoperative pain and can be practiced for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chun-Nan Yeh et al concluded a similar finding in their study that combined wound and intraperitoneal local anesthetic infiltration significantly decreased immediate postoperative pain [22].

Most of group A patients and a very few patients in group B required rescue analgesics after surgery. Majority of group B patients started receiving rescue analgesia at 6th hour of postoperative period. In a similar study, Neerja Bhardwaj et al. [15] observed that the total number of patients requiring rescue analgesic was higher in group 1(normal saline) than group 2[0.5% bupivacaine], which was statistically significant. Tata. VS Ramprasad [23] studied the total analgesic consumption in 12 hours after intra peritoneal and port sites administration of bupivacaine following laparoscopic cholecystectomy and concluded that local anesthetic administration is an effective component of multimodal analgesia for reducing postoperative pain and opioid requirement after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Only one case reported shoulder tip pain in group B. Forty-seven patients had shoulder tip pain in group A which was statistically significant in the present study. Studies by Narcho et al. [18] showed a significant decrease in shoulder pain after intraperitoneal bupivacaine. The vital parameters namely the mean heart rate, mean systolic blood pressures, mean diastolic blood pressure in both groups were calculated for the entire study period across all time points. There were statistically significant changes in the postoperative heart rate and blood pressures, in both the study groups after 30min, 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, 8 hours and 12 hours, across the study period of 24 hours.

Conclusion

Intraperitoneal instillation and peri portal infiltration of 0.25% bupivacaine after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is effective for postoperative pain relief in the initial hours with less consumption of rescue analgesics. The method is easy, simple, cost effective and minimally invasive with no adverse effects.

References

- Baxter JN, O Dower PJ (1995) Pathophysiology of laparoscopy. Br J Surg 82: 1-2.

- Berggren U, Gordh T, Haglund U (1994) Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: hospitalization, sick leave, analgesia and trauma responses. Br J Surg 81: 1362-1365.

- Bessel JR, Baxter P, Riddel P A (1996) randomized controlled trail of laparoscopic extraperitoneal hernia repair as a day surgical procedure. Surg Endos 10(5): 495-500.

- Collins LM, Vaghadia H (2001) Anesthesia for laparoscopy with emphasis on outpatient laparoscopy. Anesthesiology clinics of north America 19(1): 43-55.

- Sulekha (2013) The effect of intraperitoneal bupivacaine for postoperative pain management in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy-A prospective double-blinded randomized control study. International organization of scientific research Journal of dental and medical sciences (IOSR-JDMS) 4(5): 64-69.

- Murrat Sarac A, Baykan N (1996) The effect and timing of local anaesthesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Lap Endos 6(5): 362- 366.

- Korell M, Schmaus F (1996) Pain intensity following laparoscopy. Surg Lapar Endos 6(5): 375-379.

- Deepali Valecha, Gaurav Acharya and Kk Arora (2016) Intraperitonial bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy a comparative study. European journal of pharmaceutical and medical research (ejpmr) 3(5): 362-365.

- Maharjan SK, Shrestha S (2009) Intraperitoneal and periportal injection of bupivacaine for pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Kathmandu University Medical Journal (25): 50-53.

- Ayaz Gul, Imtiaz Khan, Ahmad Faraz, Irum Sabir Ali (2014) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: The effect of intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine on the mean post-operative pain scores, Professional Med J 21(4): 593- 600.

- Joris J, Thiry E, Paris P, Weerts J, Lamy M (1995) Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: characteristics and effects of intraperitoneal bupivacaine. Anesth Analg 81(2): 379-384.

- Hernandez Palazon J, Tortosa JA, Nuno de la Rosa V, Gimenez-Viudes J, Ramirez G et.al. (2003) Intraperitoneal application of bupivacaine plus morphine for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol 20: 891-896.

- Mraovic B, Jurisis T, Kogler-Majeric V, Sustic A (1997) Intraperitoneal bupivacaine for analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 41(2): 193-196.

- Ng A, G Smith (2002) Intraperitoneal administration of analgesia: is this practice of any utility? British journal of anesthesia 89(4): 535-537.

- Neerja Bhardwaj, Vikas Sharma, Pramila Chari (2002) Intraperitoneal bupivacaine instillation for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Anaesth 46(1): 49-52.

- Sami Hasson, Firas AL Chalabi (2013) postoperative pain reduction with bupivacaine instillation after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The Iraqi postgraduate medical journal 12(2): 186-191.

- Tsimoyiannis EC, Glantzounis G, Lekkas ET, Siakas P, Jabarin M, et.al. (1998) normal saline and bupivacaine infusion for reduction of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 8(6): 416-420.

- Narchi P, Benhamou D, Fernandez H (1991) Intraperitoneal local anaesthetic for shoulder pain after day case laparoscopy. Lancet 338: 1569-1570.

- Pasqualucci A, de Angelis V, Contardo R, Colo F, Terrosu G, Donini A et al. (1996) Preemtive analgesia: intraperitoneal local anesthetic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. Anesthesiology 85: 11-20.

- Chundigar T, Hedges AR (1993) Intraperitoneal bupivacaine for effective pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 75(6): 437-439.

- Alam MS, Hoque HW, Saifullah M, Ali MO (2009) Port site and intraperitoneal infiltration of local anesthetics in reduction of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medicine today 22(1): 24-28.

- Chun Nan Yeh, Chun Yi Tsai, Chi Tung Cheng, Shang Yu Wang, et al. (2014) Pain relief from combined wound and intraperitoneal local anesthesia for patients who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMC Surgery 14: 28.

- Tata. VS Ramprasad (2015) Efficacy of intra peritoneal and port sites administration of bupivacaine on postoperative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy – a randomized clinical trial. Indian journal of medical research and pharmaceutical sciences 2(3): 28-31.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...