Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1403

Case Report(ISSN: 2644-1403)

Cervical Blood Patch: A Case Report Of An Unusual Technique For An Unusual Diagnosis Volume 4 - Issue 1

José Francisco Cravo1*, Ionut Tabolcea1 and Turgay Tuna1

- 1Anesthesiology-Reanimation Department, Hôpital Erasme, Brussels, Belgium

Received:February 25, 2021; Published: March 05, 2021

Corresponding author: José Francisco Cravo MD, Anesthesiology-Reanimation Department, Route de Lennik 808, Hospital Erasme, 1070 Brussels, Belgium

DOI: 10.32474/GJAPM.2021.04.000181

Abstract

Cervical epidural blood patches (CEBP) remain an unfamiliar domain for most anesthesiologist as they fear the possible neurological complications related with the procedure. The injection of autologous blood as close as possible to the dural leakage site has shown to be the most effective approach for symptom resolution in case of spontaneous cervical dural tears. This case report describes in detail a feasible and effective technique to perform an epidural blood patch at the cervical level.

Introduction

Intracranial hypotension headache is almost always related to a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage due to a dural tear, which can have an iatrogenic, traumatic, or spontaneous etiology. The incidence of spontaneous dural tears is around 5 in 100.000 individuals per year [1] and it is more common in women (2:1 ratio). Its etiology and pathophysiology are unknown, and it remains a diagnosis of exclusion, when there is no previous history of trauma, spinal surgery, lumbar puncture nor an epidural neuroaxial procedure. Patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension typically present with postural headache, increasing in intensity in a sitting or upright position and achieving a significant headache relieve by laying down in a horizontal position, explained by the effect of gravity in the amount of CSF surrounding the brain. In some cases, other neurological symptoms can be present, such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, blurred vision, diplopia, tinnitus, dysgeusia, among others. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and symptoms, and confirmed by brain and spine MRI where indirect findings of a dural leak can be seen, such as the curtain sign, when an extradural fluid collection separates the dura from the bony spinal canal [2], but also the enhancement of pachymeninges, pituitary hyperemia, engorgement of venous structures and/or sagging of the brain.

Myelography can be helpful in identifying the precise site of CSF leakage. Initial management includes conservative measures based on oral analgesics and fluid hydration. In refractory patients, an invasive treatment technique may be required, known as ‘Blood patch’, characterized by the injection of autologous blood in the epidural space. In this patient’s case, we report a feasible and effective cervical blood patch technique, based on the utilization of an epidural catheter introduced at a lower cervical level, to reach a cervical CSF leakage at a higher cervical level, where the risk of complications of a cervical epidural blood patch (CEBP) would be higher. This case report was approved by the local Ethics Committee with the reference code P2020/644, patient’s written informed consent was obtained and signed, and EQUATOR’s guidelines were followed in its elaboration.

Case Description

A 35-year-old female patient presents to a Pain Management Clinic consultation on a secondary center, referred to by her General Practitioner, with a proposal of bilateral infiltration of the greater and lesser occipital nerves in relation with 4 weeks lasting bilateral headache. The patient describes her pain as an intense tight band around the head, affecting her cervical and occipital regions as well. The pain appeared at the first rise in the morning and significantly decreased in supine position. The palpation of the occipital and cervical region did not alter the pain’s character nor intensity. The patient had no relevant past medical history nor history of recent trauma. This clinical description led the attending physician to cancel the planned infiltration and proceed to further diagnostic evaluation with the realization of a head and total spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), leading to the diagnosis of a cervical dural tear with an adjacent extradural liquid collection at C2C3 level. The MRI showed also signs of intracranial hypotension like hypophyseal hyperemia, venous plexus engorgement and pachymeningeal enhancement. Conservative treatment was instaured with oral hydration and analgesics, and the patient was referred to a tertiary center capacitated to perform cervical blood patches. The CEBP was performed by a team composed of two experienced anesthesiologists, an anesthesiology trainee, and a nurse.

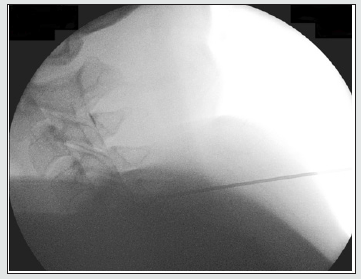

Figure 1: Fluoroscopy profile view of the introduction of a 17G Tuohy needle into the epidural space, at the C5C6 level

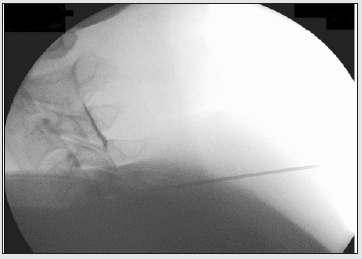

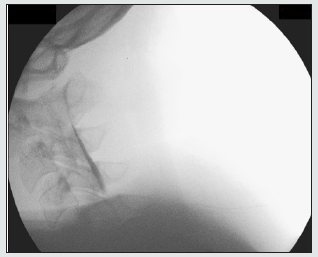

The procedure’s details and its potential risks were explained to the patient and she was asked to fast for 6 hours before the procedure. An intravenous line was placed upon arrival in the operating room. The patient was placed in prone position on the operating table and the fluoroscope positioned in order to allow the team to easily obtain both an anteroposterior and a profile view. The posterior aspect of the cervical region was disinfected with a 2% Chlorhexidine solution. Under local anesthesia with Lidocaine 2%, a 17G Tuohy needle was introduced into the epidural space at the C5C6 level (Figure 1), under fluoroscopy guidance and using the hanging drop technique. An epidural catheter was introduced still under fluoroscopic control, with the catheter tip reaching the C2C3 level, where the dural tear was detected in the diagnostic imaging studies. There was no blood nor cerebrospinal fluid upon aspiration testing. The catheter tip position was confirmed by the injection of a total of 2 ml of contrast solution (Figure 2). The Tuohy needle was then removed, leaving the epidural catheter in place (Figure 3) while the team proceeded to a sterile blood withdraw from a peripheral vein, and a total of 10 ml were injected through the epidural cervical catheter. The patient remained under surveillance on the recovering room for 4 hours, in a strict dorsal decubitus. There were no complications related with the procedure and neurological examination before discharge was strictly normal. The patient’s follow-up consisted of a telephonic consultation one week after the procedure and a standard pain clinic consultation 20 days later, where the patient complained of remaining mild cervicalgia, but the typical symptoms of intracranial hypotension headache were no longer present. A follow-up cervical spine MRI was performed, and it resulted completely normal, showing no signs of intracerebral hypotension, cervical dural tear nor extradural or paravertebral fluid collections.

Figure 2: Contrast product was injected through an epidural catheter confirming its position at the C2C3 level.

Figure 3: After removal of the Tuohy needle, the epidural catheter remained in place, at the C2C3 level. Diffused contrast product remains visible in the epidural space

Discussion

Spontaneous CSF leakages occur most commonly at the cervicothoracic spine, but lumbar leakages have been described [3]. Although some reports showed that a lumbar EBP may lead to a partial, and sometimes, even complete symptom resolution independently of the leakage origin [4], literature demonstrates that an EBP close to the site of CSF leak is more effective [5]. Currently accepted hypothesis suggests that the increase in hydrostatic pressure resulting from the acute compression of the thecal sac might provide an immediate, partial, or complete relief of symptoms, but this effect being brief; while the dural leak sealing by the tamponade effect provided by the blood clot would be responsible for the permanent resolution of symptoms, allowing the gradual restoration of CSF volume. Even though an epidural blood patch close to the leakage site seems to be more effective, most anesthesiologists are more experienced in lumbar EBP and in lumbar epidural space approach in general, while the cervical approach remains an unfamiliar domain, mainly due to the higher risks involved in relation with the narrower diameter of the cervical epidural space. Possible complications associated with a cervical EBP range from minor complications, such as local pain or radiculopathy, to more severe cases including direct spinal cord injury, spinal cord compression and spinal cord infarction, all of which may lead to paraplegia, tetraplegia and even death [6]. All the previously mentioned complications, except for local pain at the site of injection, are deemed rare, and to our knowledge, besides a few punctual case reports, there is no reliable statistical data on their incidence and frequency.

Until now, there are no published studies evaluating the exact volume that should be injected when performing a cervical EBP but a literature review by Kapoor et al., showed that volumes up to 15mL of blood have been injected in the epidural space at the cervical level, and up to 20mL at the C7-Th1 level, without any serious complications [6]. Therefore, in this patient’s case, a safest technique was chosen, by approaching the cervical epidural space at a lower level (C5C6), where the epidural space diameter is larger than at the upper cervical levels, and an epidural catheter was then introduced under fluoroscopy guidance up to the dural leakage level. Position confirmation was obtained by contrast injection, allowing the delivery of a total volume of 10mL, the closest to the leakage site as possible, maximizing the efficiency of the procedure. There are no standard of care guidelines establishing how cervical EBPs should be performed. Regarding the patient’s position, the existing reported cases preferred the use of prone position, and in fewer cases the lateral decubitus.

In terms of imaging guiding techniques, fluoroscopy was the chosen option in most of the cases described in literature, more than computerized tomography, this results mainly from easier access and availability, as well as higher level of practical experience with the technique. In the reported case, we chose the prone position with slight cervical flexion to promote the theoretical increase in the cervical epidural space of 1 to 2mm [7], and we used fluoroscopic guidance mainly due to prompt availability and higher degree of experience of the operators with this type of imaging technique. Concerning the cervical EBP technique itself, we considered that the patient’s safety should remain the top priority, so we preferred a lower-level puncture approach plus epidural catheter introduction up to the leakage site, rather than a direct leakage level puncture at an upper cervical level, which would pose a higher risk of procedural complications due to narrower epidural space diameter at this level.

Conclusion

Cervical EBP is considered the most effective treatment of refractory hypotension headache secondary to a cervical dural CSF leakage. The number of studies and reported cases in literature related with cervical EBP remain sparse and limited, while procedure related safety and potential complications are the main concerns among anesthesiologists. This patient’s case intends to report the procedural aspects and details related with the performance of a cervical EBP to treat a spontaneous cervical dural tear at C2C3 level, where the use of an epidural catheter introduced at C5C6 level reaching up to the level of the dural tear, allowed to avoid a riskier approach at a higher cervical level. This case report demonstrates a feasible, safe and effective EBP technique to approach high cervical level dural tears.

Supporting Information

Financial Disclosures: None

Conflicts of Interest: None

Author’s Individual Contribution

a. José Francisco Cravo: This author helped in the patient’s management and follow-up, as well as in the elaboration and redaction of the manuscript.

b. Ionut Tabolcea: This author helped in the patient’s management and follow-up, as well as in the elaboration and editing of the manuscript.

c. Turgay Tuna: This author helped in the patient’s management and follow-up, as well as in the supervision, editing and correction of the manuscript.

Glossary of Terms

CEBP-Cervical Epidural Blood Patch; CSF-Cerebrospinal Fluid; EBP-Epidural Blood Patch; EQUATOR-Enhancing the Quality and Transparency off Health Research; MRI-Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

References

- Liaquat M, Jain S (2020) Spontaneous intracranial hypotension, Stat Pearls.

- Pabaney A, Mirza F, Syed N, Ahsan H (2010) Spontaneous Dural tear leading to intracranial hypotension and tonsillar herniation in Marfan syndrome: a case report. BMC Neurology article (54).

- Nipatcharoen P, Tan S (2011) High thoracic/cervical epidural blood patch for spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak: a new challenge for anesthesiologists. Anesthesia & Analgesia 113(6): 1476-1479.

- Ferrante E, Arpino I, Citterio A (2006) Is it a rational choice to treat with lumbar epidural blood patch headache caused by spontaneous cervical CSF leak? Cephalalgia 26(10): 1245-1246.

- Cousins M, Brazier D, Cook R (2004) Intracranial hypotension caused by cervical cerebrospinal fluid leak: treatment with epidural blood patch. Anesthesia & Analgesia 98(6): 1794-1797.

- Shruti K, Shibab A (2015) Cervical epidural blood patch-a literature review. Pain Medicine 16(10): 1897-1904.

- Shim E, Lee J, Lee E, Ahn J, Kang Y et al. (2017) Fluoroscopically guided epidural injections of the cervical and lumbar spine. Radio Graphics 37(2): 537-561.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...