Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4676

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4676)

Farmer’s Perspective on Importance and Constraints of Seaweed Farming in Sri Lanka Volume 3 - Issue 1

GAS Ginigaddara* and AYA Lankapura

- Department of Agricultural Systems, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka

Received: May 01,2018; Published: May 29,2018

Corresponding author: GAS Ginigaddara, Department of Agricultural Systems, Faculty of Agriculture, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Puliyankulama, Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka

DOI: 10.32474/CIACR.2018.03.000151

Abstract

Seaweed cultivation is identified as a catalyst for social progression in coastal communities. Despite the potentials, the seaweed cultivation introduced to resettled coastal districts in Sri Lanka seems not performing to the expectations owing to various reasons. Farmers’ perspective as the leading stakeholders would facilitate the understanding of such a complexity. Therefore, the study attempted to assess the values and constraints related to seaweed farming as perceived by the seaweed farmers. Two-stage stratified random sampling technique was employed to draw a sample of 160 seaweed growers from the purposely-selected coastal areas of northern Sri Lanka. A perceived ordinal ranking method was exercised to assess the perceived importance, whilst Garrett’s ranking technique to detect the judgment of the farmers about the constraints. Next to fishing, seaweed farming received the highest perceived importance of the respondents. Favourable income and employment generation, the ability to easily manage with fishing, supportive role in empowering women and the existence of a favourable contract growing system were among the major causative responses contributed to the perceived importance. Major constraints identified in sea weed farming were adverse weather pattern (19.6%), poor quality of existing planting materials (16.68%), distortions prevailing in the purchasing mechanism (14.7%) and improper aquatic environments (13.74%). Thus, the study concluded that seaweed farming is perceived as an important livelihood option for the coastal communities and developing strategies to mitigate the impact of adverse environmental changes would promote seaweed cultivation.

Keywords: Constraints; Perceived importance; Seaweed farming; Sri Lanka

Introduction

Seaweed cultivation has become increasingly popular as one of the most important economic activities that can be practiced in the coastal regions. The potential role that seaweed could play in rural development being as a catalyst of social progression [1] by rendering extensive employment opportunities [2] to the coastal communities has already been identified. Accordingly, the government of Sri Lanka has introduced seaweed farming to resettled coastal districts in the northern part of the country to improve socio-economic conditions in vulnerable regions through the promotion of sustainable livelihood development. However, the available sporadic information in this regard imply that the level of performance seems to be suppressed by issues such as harsh weather conditions [3-5] and improper aquatic environments, which were commonly associated with seaweed farming. In this backdrop, assessing the value and constraints related to seaweed farming as perceived by the beneficiaries would uncover trustworthy, qualitative and in-depth information that would otherwise not become known. Such information would be essential for future planning by the policy makers for a better design to meet the farmer needs and can be useful both to fine-tune and enhance the effectiveness of the existing seaweed cultivation system.

Methodology

This study was conducted in purposely-selected coastal areas of Jaffna and Kilinochchi districts, located in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka (Figure 1). Two-stage stratified random sampling technique was employed to select 03 Divisional Secretariat (DS) divisions and 04 Grama Niladhari (GN) divisions respectively and finally to draw a sample of 160 seaweed growers. The required primary data were mainly collected through a structured and pre-tested questionnaire, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The perceived ordinal ranking method as previously adopted by Crawford [6] was exercised to assess the perceived importance of seaweed growers towards different livelihood options, whilst Garrett’s ranking technique [7-9] was exercised to detect the judgment of the farmers about the constraints faced by them in seaweed cultivation.

Results and Discussion

Farmers’ perceived importance towards seaweed farming

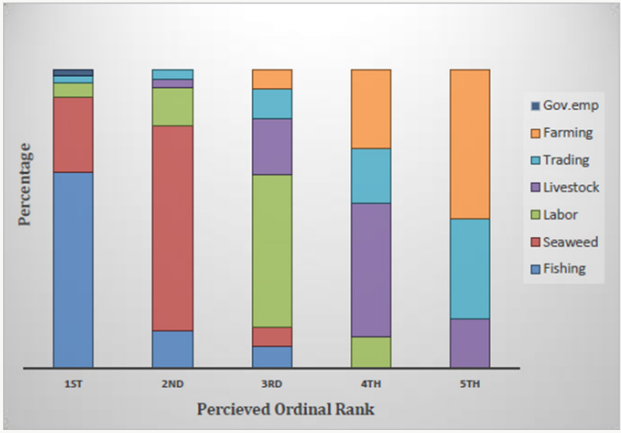

Next to fishing, seaweed farming received the highest perceived importance of the respondents. Accordingly, sea weed farming was perceived by 94% of farmers as either first or second in importance (Figure 2). The reasons behind the perceived importance were satisfactory income and generation of employment, easily manageable nature with fishing, cooperative role in women empowerment and the prevailing promising contract growing system (Figure 2). Being an economically viable alternative livelihood option [10], seaweed farming has diversified the livelihood options of the farming communities and thereby has provided a stable annual average income, which improves household economic resilience [11] enabling a sustainable way of life. This finding is in conformity with the findings of Zacharia [12] and Tobisson [13] on the role of seaweed farming in coastal livelihood improvement. On the other hand, previous studies have identified the possibility of developing employment-incomeconsumption relationships related to the seaweed farming [2]. This employment potential [6,14] is highlighted by the participants and viewed that harvesting and initial preparation stages render extensive employment opportunities. Especially, the shallow water seaweed farming allows more involvement of women and renders more employment opportunities for women during initial preparation and harvesting stages.

The interviewees identified that the seaweed farming is instrumental in empowering women [13,15] within the study area. Further, it was reported that without being much disturbing to the primary economic activity, the seaweed farming can be easily integrated with conventional fishing. Moreover, it was identified that seaweed farming requires lesser time for its maintenance after planting and allows farmers to engage in other activities as well. Altogether, these major causative responses led to the perceived importance and will assist in promoting the seaweed cultivation within the study area. Apart from these major causes the provision of rapid return on investment, the requirement of simple farming techniques and an alternative for deprivation of terrestrial lands for cultivation also affected for the perceived importance towards seaweed farming.

Constraints for seaweed farming

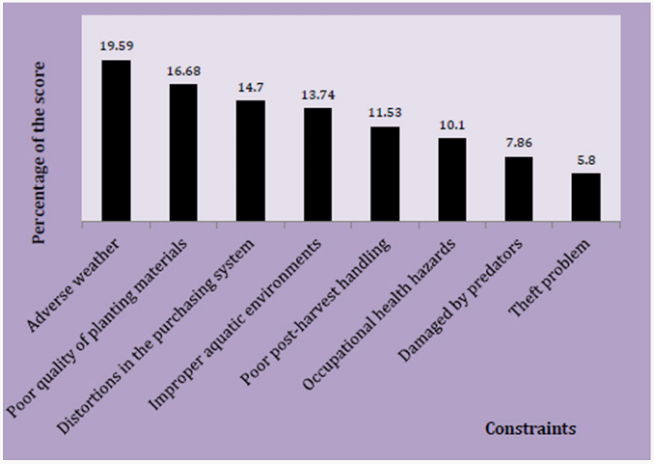

The results indicated that the adverse weather pattern (19.6%) is the major constraint faced by the seaweed farmers within the study area and obtained the highest rank. In conformity to the findings of Zamroni [3], the seasonal changes associated with monsoonal weather pattern is critically affecting the seaweed cultivation by limiting it to four cultivation seasons per year. Further, heavy rains and severe weather conditions like prolonged higher temperature periods regularly disturb the seaweed cultivation. These unfavorable changes would ultimately affect both quality and quantity [16] of seaweed harvest (Figure 3). Consisting with the findings of Zamroni [3], the poor quality of planting materials (16.68) obtained the second highest rank as a major constraint faced by the seaweed farmers. Farmers ordinarily use traditional self-propagation techniques using cuttings of the previous harvest. However, inferior strains created by overutilization of the old seaweed stocks may have negatively affected the growth rate and quality of seaweed and avoided growers from optimizing their yield.

The study identified that the buyers adopted a contract growing system as the purchasing mechanism of seaweed. Such mechanisms were further reported in the studies of Krishnan [3,17] and Hurdato (2013) related to seaweed farming. As identified by the study, low farm gate price, sporadic payments, and defective weighing processes have distorted (14.7) the qualities of the existing purchasing system. The respondents also viewed that the buyers regularly justify these low prices, highlighting the importance of technical provisions like raw materials and advisory support, which are mainly provided by them. Conversely, few growers believed that non-existence of layers of intermediaries and protection from time to time price fluctuations would still make the contract growing system more favourable.

The ideal aquatic environment provided in near-shore areas is favourable for sea weed farming. However, due to high competition and legal cut-offs imposed by the local authorities’ farmers haveshifted the cultivation to less fertile improper aquatic environments (13.74). Seaweed-farming locations were co-managed by coastal villagers and idled seaweed farms also contributed to this problem. Participants also indicated that seaweed cultivation locations away from the near-shore areas increased the overall production cost due to the expenses incurred for extra transportation.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Based on the logical interpretation of the findings, it can be concluded that seaweed farming is perceived as an alternative livelihood option for the coastal communities. This social acceptability implies the possibility of further expanding seaweed farming to other matching locations as a commercial enterprise. The adverse weather pattern was the major constraint perceived by the seaweed growers. In order to promote the existing system, the establishment of a weather damage relief program from the government, early warning system of sudden environmental changes and commercial level seaweed nurseries are recommended. Further, the collaborative action between key stakeholders is identified as a necessity to promote the seaweed industry.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to acknowledge the financial support offered for the research study by National Agribusiness Development Program, Presidential Secretariat, and Sri Lanka.

References

- Prado VV, Junio IC, Tepait EV, Galvez GN, Bisco LP, et al. (2012) 2 in 1 plus mariculture farming system (A Livelihood Management Strategy for Coastal Families). International Scientific Research Journal 4(3): 204-213.

- Krishnan M, Narayanakumar R (2010) Structure, conduct and performance of value chain in seaweed farming in India. Agricultural Economics Research Review 23: 505-514.

- Zamroni A, Yamao M (2011) Coastal Resource Management: Fishermen’s Perceptions of Seaweed Farming in Indonesia. International Journal of Biological, Biomolecular, Agricultural, Food and Biotechnological Engineering 5(12): 32-38.

- Hurtado AQ, Agbayani RF, Sanares R, de Castro Mallare MTR (2001) The seasonality and economic feasibility of cultivating Kappaphycus alvarezii in Panagatan Cays, Caluya, Antique, Philippines. Aquaculture 199(3-4): 295-310.

- Neish IC (2013) Social and economic dimensions of carrageenan seaweed farming in Indonesia. Social and economic dimensions of carrageenan seaweed farming, Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper (580): 61-89.

- Crawford BR, Shalli MS (2007) A Comparative Analysis of the Socio- Economics of Seaweed Farming in Two Villages along the Mainland Coast of Tanzania.

- Christy RJ (2014) Garrett’s Ranking Analysis of Various Clinical Bovine Mastitis Control Constraints in Villupuram District of Tamil Nadu. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) 7(4): 62-64.

- Zalkuwi J, Singh R, Bhattarai M, Rao OS (2015) Analysis of Constraints Influencing Sorghum Farmers Using Garrett’s Ranking Technique; A Comparative Study of India And Nigeria. International Journal of scientific research and management (IJSRM) 3(3): 2435-2440.

- Dhanavandan S (2016) Application of Garret Ranking Technique: Practical approach. International Journal of Library and Information Studies 6(3): 135-140.

- Narayankumar R, Krishnan M (2011) Seaweed mariculture: An economically viable alternate livelihood option (ALO) for fishers. Indian Journal of Fisheries 58(1): 79-84.

- Crawford B (2002) Seaweed farming: An alternative livelihood for smallscale fishers. Narragansett (RI): Coastal Resources Center, USA.

- Zacharia PU, Kaladharan P, Rojith G (2015) Seaweed Farming as a Climate Resilient Strategy for Indian Coastal Waters. In The International Conference on Integrating Climate, Crop, Ecology-The Emerging Areas of Agriculture, Horticulture, Livestock, Fishery, Forestry, Biodiversity and Policy pp. 59-62.

- Tobisson E (2013) Coping with Change: Local Responses to Tourism and Seaweed Farming in Coastal Zanzibar, Tanzania. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science 12(2): 169-184.

- Radhika RSR, Gayathri S (2014) Women Enterprising in Seaweed Farming With Special References Fisherwomen Widows in Kanyakumari District Tamilnadu India. Journal of Coastal Development 17(1): 1-5.

- Abowei JFN, Ezekiel EN (2013) The potentials and utilization of Seaweeds. Scientia Agriculturae 4(2): 58-66.

- Valderrama D, Cai J, Hishamunda N, Ridler NB (2013) Social and economic dimensions of carrageenan seaweed farming. FAO, Rome, Italy.

- Krishnan M, Narayanakumar R (2013) Social and economic dimensions of carrageenan seaweed farming Social and economic dimensions of carrageenan seaweed farming. Fao Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 580(204): 163-184.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...