Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4676

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4676)

Causes and risk factors influencing persistence of Foot and Mouth Disease outbreaks in Kyotera district, Uganda Volume 9 - Issue 5

Tashoroora O1, Erechu RS1, Higenyi J1, Nanfuka ML1, Ademun AR1, Kimbugwe E2, Lutaaya2, Ndyanabo JM3, Ayebazibwe C3, Nizeyimana G3, Okuthe S3 and Magona JW*3

- 1Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries, Entebbe

- 2Veterinary Department, Kyotera district, Kyotera

- 3Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations, Kampala, Uganda

Received: December 13, 2021; Published: December 20, 2021

Corresponding author: Magona JW, Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations, Kampala, Uganda

DOI: 10.32474/CIACR.2021.09.000324

Abstract

A Participatory Disease Search was conducted in Kyotera District with the aims of understanding trends in Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) outbreaks during the period (2009-2019), associated risk factors and the epicenter or origin responsible for persistence of FMD outbreaks along the Uganda-Tanzania border. A team of four people from MAAIF visited subcounties of Kakuto, Kabira, Kyebe, and Town Councils of Kasensero and Mutukula in Kyotera District. Data collection was through key informant semistructured interviews guided by checklist and focus group discussion with a total of 62 livestock keepers: 8-14 per Subcounty. Other PDS tools employed included, ranking using pairwise ranking and proportional piling, and visualization using mapping, timelines and seasonal calendar. Over the period (2009-2019), Kyotera district had had the last FMD outbreak in 2016. Seasonal occurrence was mainly during dry seasons (June to September). Outbreaks were rare during wet seasons: March to May or October to December. Regarding risk factors, they included (1) Breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone (Mean Score 14.0, 95% CL (13.98 - 14.02); (2) Ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (Mean Score 12.4, 95% CL (12.36 - 12.44); (3) Uncontrolled movement of animals (Mean Score 10.8, 95% CL (10.75 - 10.85); (4) Porous unmanageable borders (Mean Score 10.4, 95% CL (10.34 - 10.46); (5) Inadequate vaccines (Mean Score 9.2, 95% CL (9.18 - 9.22); (6) Ineffective quarantine (Mean Score 7.6, 95% CL (7.58 -7.62) ; (7) Inadequate veterinary staff (Mean Score 3.8, 9.5% CL (3.76 -3.84); (8) High cost of vaccines (Mean Score 2.2, 95% CL (2.16 - 2.24 ); and (9) Presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Mean Score 0.6, 95% CL (0.58 – 0.62). Free movement of livestock from grazing areas in districts adjacent to Lake Mburo National Game Park, and from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve in Tanzania to Kyotera district through Koza Triangle was the cause of persistent FMD outbreaks. In conclusion, vaccination (Mean score 54.40%, 95% CL (54.26 - 54.54)), animal movement control (Mean Score 41.60%, 95%CL (41.24 - 41.96)) and closure of markets (Mean Score 4.00%, 95% CL (3.75 - 4.25) were considered the most important control measures for FMD. Regular and consistent buffer vaccination targeting the border subcounties and Koza Triangle was the most effective approach for containing FMD outbreaks.

Keywords: Causes; FMD persistent outbreaks; Uganda-Tanzania border; Kyotera District

Introduction

Livestock significantly contributes to many agricultural-based economies and livelihood of rural poor communities, especially the smallholder farmers who form a large proportion of livestock keepers in developing countries (FAO, 2005). In sub-Saharan Africa, it contributes 30% to agricultural GDP with cattle contributing nearly 60% of the value of livestock products (AU-IBAR, 2010). In Uganda, the livestock sector is an important component of the agricultural sector, contributing 5 and18 percent to the National GDP and agricultural GDP, respectively. The sector is on steady growth of about 3 percent per annum. The livestock population comprises of cattle at 12.8 million, poultry 42 million, pigs 3.6 million; goats 4 million and sheep 3.8 million. It is estimated that 4.5 million households (70.8%) in the country rear at least one kind of livestock. Consequently, livestock production is part of the country’s vision for economic development, food security and poverty reduction and has been given attention in Uganda’s National Development Plan II and the Agricultural Sector Strategy Plan (2015-2020)[1].

Despite its importance, livestock production and productivity is severely constrained by transboundary animal diseases (TAD) suchas FMD that causes huge economic losses in the livestock industry globally. It is a highly contagious disease affecting all cloven-hoofed animals, and endemic in parts of Asia, Africa, Middle East and South America (Kitching et al. [2]. Typical clinical signs of FMD in cattle include: pyrexia (up to 42°C), anorexia; in dairy animals, reduced milk volume for 2-3 days. Vesicles develop on the buccal and nasal mucous membranes and/or between the claws and coronary band. These may lead to: smacking of lips, bruxism, drooling, lameness, stamping or kicking of feet. Vesicles frequently also develop on the mammary glands and rupture, leaving erosions 24 hours later. Cattle generally recover from FMD within 8-15 days, but complications may include: tongue erosions, secondary infection of lesions, hoof deformations, mastitis and permanent impairment of milk production, abortion, and permanent weight loss. Young animals may die from viral myocarditis (Queensland Government, 2019). On a continental scale, FMD occurred in 26 countries, including Uganda in 2014 representing a 13% increase in the number of affected countries from the previous year (PAARYB, [3]). FMD is one of the most widely distributed transboundary animal diseases on the African continent. A total of 1246 outbreaks of FMD were reported from 26 countries in 2014. With a total of 56,042 cases leading to 948 deaths were reported from the infected countries, with an estimated case fatality rate of 1.77% (PAARYB[3]). Burkina Faso (350) followed by Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (189) and Algeria (162) reported the highest number of fatalities. FMD outbreaks were reported in different species of animals including bovine, buffaloes, caprine, ovine and porcine (Paaryb, [3]). Based on the reports received from the affected Member States (MS), the highest number of FMD outbreaks was reported in August followed by July and November (PAARYB, 2014). In the East Africa Community 5 countries including, Burundi (1), Kenya (48), South Sudan (5), Tanzania (14), and Uganda (8) reported FMD outbreaks (PAARYB, [3]).

In Uganda, highly contagious and infectious diseases which are associated with high socio-economic impact constitute the most limiting constraint to livestock sector development (MAAIF, 2005, 2010). FMD is considered one single most important disease associated with enormous widespread occurrence in Uganda (Rutebarika, [4]) with enormous financial losses especially in the smallholder farmers in the rural communities. The losses are estimated at US dollars: 595, 198 and 26 for mortality loss, salvage loss and FMD control per head of cattle respectively (Baluka et al., [5]). Six serotypes, including, A, O, C, SAT1, SAT2, and SAT3 exist in Uganda. FMD outbreaks have been reported in the Uganda-Tanzania border districts of Isingiro (May 2015) and Rakai (February and July 2015). It re-emerged in central Uganda as well in June; Nakaseke July 2015, Kyakwanzi (July 2015), Luwero (June 24th 2015 and July 18th 2015), Mukono (July 8th 2015), and Mpigi (July 22nd 2015). Consistent and frequent FMD outbreaks have been reported in Uganda, particularly in districts bordering Tanzania. Their causes and risk factors responsible have not been documented. Hence a participatory disease search was conducted in Kyotera district.

Materials And Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted in Kyotera district that borders Masaka district in the North, Lake Victoria in the East, Tanzania in the South and Rakai and Lyatonde districts in the West. It has an estimated livestock population of 203,559 cattle, 153,756 Shoats and 23,180 pigs. In terms of livestock facilities, the district has 2 livestock market, 2 abattoirs (slaughterhouses) 2 slaughter slabs and 10 milk collection centres. The district has a sub-humid climate. It receives an annual rainfall of 1000–1500 mm and has daily mean temperatures ranging between 18°C (minimum) and 30 °C (maximum). The vegetation is savannah grassland interspersed with bushy shrubs. Part of the district is densely populated and most farmers practise mixed crop-livestock farming. Modern specialized dairy farmers with Friesian crosses kept under zerograzing (stallfeeding system) exist. In a large part of the district, a pastoral farming system is practised. Pastoral herds with mainly Ankole and Zebu cattle do graze on bushy communal pastures along the areas in the cross-border along the Uganda-Tanzania border.

Selection of study sites

The District Veterinary Officer selected five sub-counties, including, Kakuto, Kabira, Kyebe, Kasensero and Mutukula for the study based on the FMD risk and previous FMD outbreaks.

Study design

The study design employed a Participatory Disease Search/ Participatory Epidemiology (PDS/PE) approach (Catley & Berhanu, [6]; CAHO, [7]). A team of four people from the Ministry of Agriculture Animal Industry and Fisheries conducted informal interviews of key informants. The key informants consisted of the District Production and Marketing Officer; the District Veterinary Officer; the veterinary staff based in the sub counties visited; the local leaders at district and sub county level; and the opinion leaders in sub counties visited. Available secondary data was as well collected. For purposes of clear understanding, a case definition for FMD had the following major clinical signs: Pyrexia (up to 42°C); Anorexia; in dairy animals, reduced milk volume for 2-3 days; Vesicles on the buccal and nasal mucous membranes and/or between the claws and coronary band; smacking of lips; bruxism; drooling, lameness; and stamping or kicking of feet.

Participatory Disease Search tools

Focus group discussions with livestock keepers were conducted in Kakuto, Kabira, Kyebe, Kasensero and Mutukula subcounties guided by a checklist and observations. Ranking using simple ranking, pairwise ranking, and proportional piling was conducted. In addition, visualization was carried out using mapping, timelines and seasonal calendars. Focus group discussions helped assess knowledge of communities on: (1) Common livestock diseases and their relative importance; (2) Familiarity with clinical signs of FMD; (3) Awareness on FMD-related mortality; (4) Awareness on FMD risk factors; (5) Effectiveness of FMD control measures; (6) Trends in FMD outbreaks, and (7) FMD epicentre or its origin and how it spreads.

The checklist for a Participatory FMD Disease Search elaborated the following: (1) Avoiding mentioning FMD before the communities; (2) Introducing the appraisal team as an animal health appraisal; (3) Identifying the respondents and establishing if they are livestock owners; (4) Establishing their main herding locations (mapping); (5) Identifying the current cattle disease problems in their herds in the Subcounties. If pyrexia (up to 42°C); anorexia; in dairy animals, reduced milk volume for 2-3 days; vesicles on the buccal and nasal mucous membranes and/or between the claws and coronary band were mentioned then FMD was explored for in details; (6) Identifying current cattle problems in Kyotera district; (7) Historically, what the most important disease problems of cattle were in Kyotera district- Invariably FMD was expected to be mentioned in the response to this question if the livestock owners had experienced outbreaks then; (8) Whether they had personally seen FMD cases in their lifetimes and what it looked like; (9) When was the last time their cattle were affected by FMD and where it came from; and (10) What conditions favored occurrence of FMD outbreaks. In addition, further probing questions were to add to cross-check reports made in other interviews, coupled with defining climatic patterns and livestock uncontrolled movement which did affect FMD epidemiology or that contrasted outbreaks with previous outbreaks in regard to the severity of disease.

Data storage and analysis

The data obtained from the participatory methods was entered and stored in Microsoft Excel software. For data analysis, descriptive statistics was performed.

Results

Findings of key informant interviews

At the time of the visit, Kyotera district did not have an active FMD outbreak. The district had had the last FMD outbreak in 2016 which spread to all sub counties. The outbreak was very severe to the extent that some of the vaccinated herds came down with the disease. FMD vaccines used then were not able to adequately contain the outbreak due to non-response.

Regarding risk factors, the following were proposed:

• Inadequate vaccination coverage of the buffer zone along the Uganda-Tanzania border

• Porous border between Uganda and Tanzania which encourages free movement of animals from Uganda to Tanzania or vice versa

• Free movement of livestock between grazing areas around Lake Mburo National Game Reserve and Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve in Tanzania and other areas of Kyotera district

• Unharmonized strategies for FMD control between the Ugandan and Tanzanian side of the border

• Poor coverage of all FMD serotypes circulating in the district by the available FMD vaccine

• Political and economic disruption of quarantines and livestock movement control programmes

• Existence of wildlife reservoirs for FMD virus infection such as Buffalos in Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve in Tanzania and Lake Mburo National Game Park Maramagambo forest, neighbouring Kyotera district

• Free interaction of wild animals (especially Buffaloes) from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve and Lake Mburo National Park with domestic animals which increases chances of FMD spread from the natural reservoirs

• Frequent droughts and the associated shortage of water and pasture especially on the Ugandan side that trigger frequent livestock movement.

As for the epicenter or origin of FMD outbreaks to Kyotera district, Koza Triangle is normally the entry point for outbreaks. Koza is a border village where boundaries of districts of Kyotera, Rakai, Isingiro and Tanzania meet. FMD usually spreads to Kyotera district from Koza triangle through movement of livestock from grazing areas in districts adjacent Lake Mburo National Game Park, such as Lyatonde, Rakai and Isingiro and from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve in Tanzania.

Key informants recommended a number of control measures that have been proven to be quite effective in Kyotera district. They included the following:

• Maintaining of livestock Check Points in the district

• Containing FMD outbreaks through buffer vaccination targeting the border subcounties and Koza Triangle

• Involvement of communities and livestock owners in FMD surveillance and control

• Involvement of other Government bodies such as Internal Security Organization, Police and Local Councils in controlling of livestock movement through Check Points

• Existence of a Memorandum of Understanding between Uganda and Tanzania to strengthen collaboration and harmonization of control of Transboundary Animal Diseases along the Uganda –Tanzania border

• Cross-border collaboration and its probable strengthening through a cross-border project between Uganda and Tanzania Governments for control of Transboundary Animal Diseases along the Uganda-Tanzania border

• Limiting the period of time for implementation of movement control through quarantines to avoid economic effects associated with livestock market closures in the district

• Securing of FMD vaccines from Government (controlled source) rather than procuring from private sector (uncontrolled source) appears to be a more effective strategy for FMD control

• Relocation of livestock markets 20 km away from the border for better monitoring and control of livestock movement

Findings of focus group discussions

Focus groups consisted of 12, 16, 8, 14 and 12 livestock keepers in Kakuto, Mutukula, Kasensero, Kyebe and Kabira Subcounties, respectively.

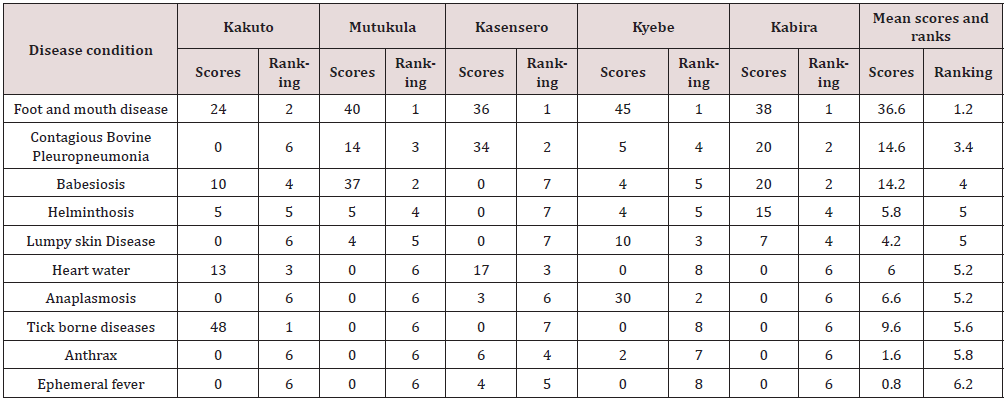

Common livestock diseases and their relative importance

Tick-borne diseases, Foot and Mouth Disease, Helminthosis, Lumpy skin disease, Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (CBPP), Ephemeral fever, Anthrax and Blackquarter were common diseases identified by focus groups. Foot and Mouth Disease had the highest score (36.6%) in terms of relative importance across the subcounties, followed by Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (14.2%) and then Babesiosis (14.2%) as presented in Table 1.

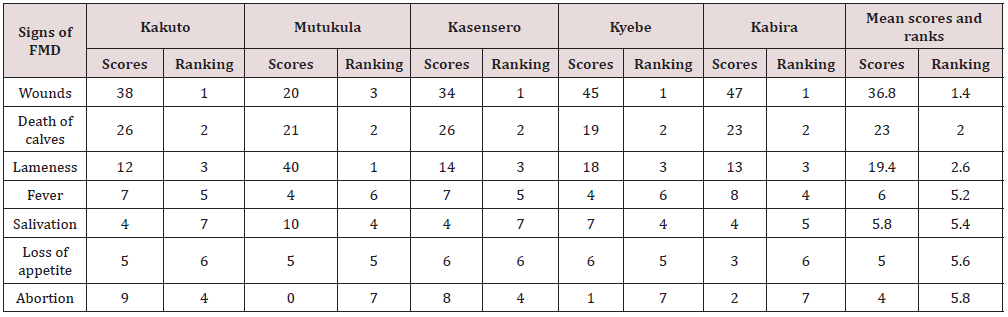

Familiarity with clinical signs of FMD

Livestock keepers across the subcounties visited recognized mainly wounds (36.8%), death of calves (23%), and lameness (19.4%) as key clinical signs of FMD (Table 2). Meanwhile, fever (6%), Salivation (5.8%), loss of appetite (5%) and abortion (4%) were considered less consistent clinical signs.

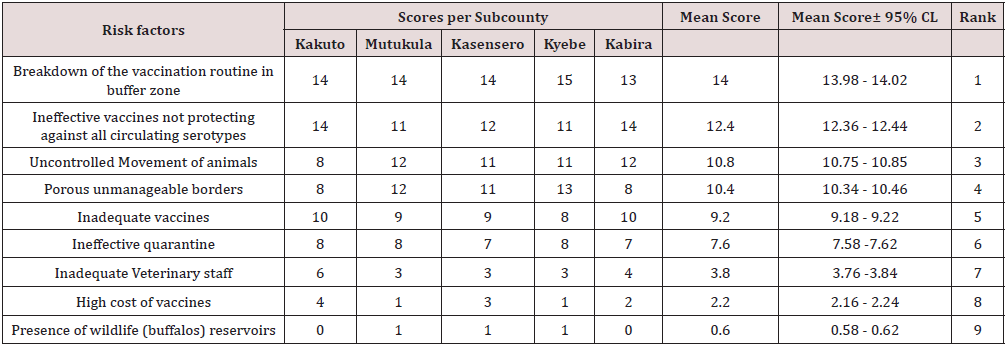

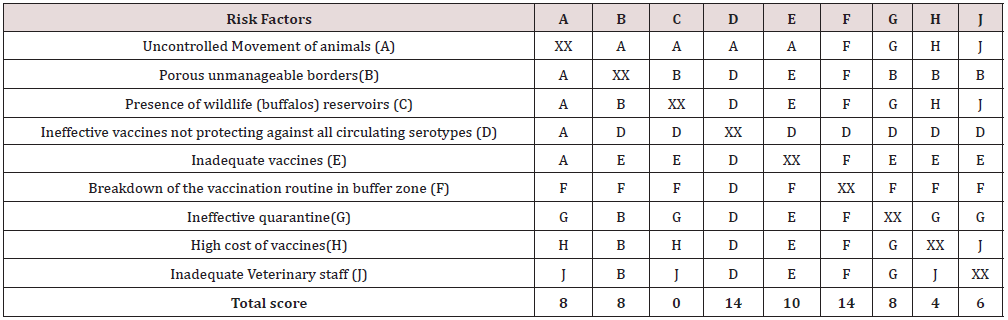

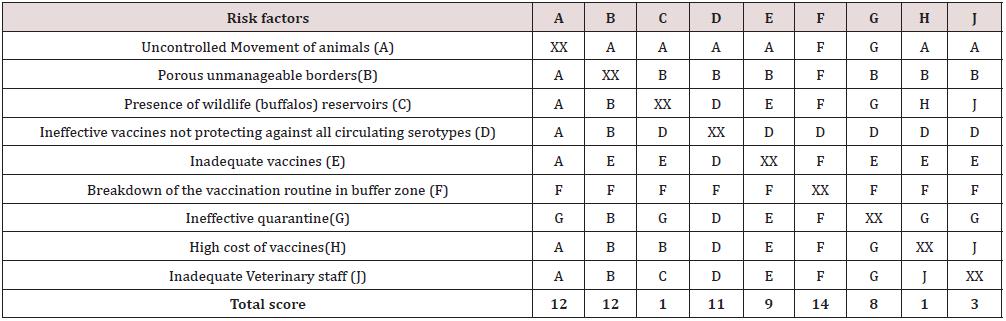

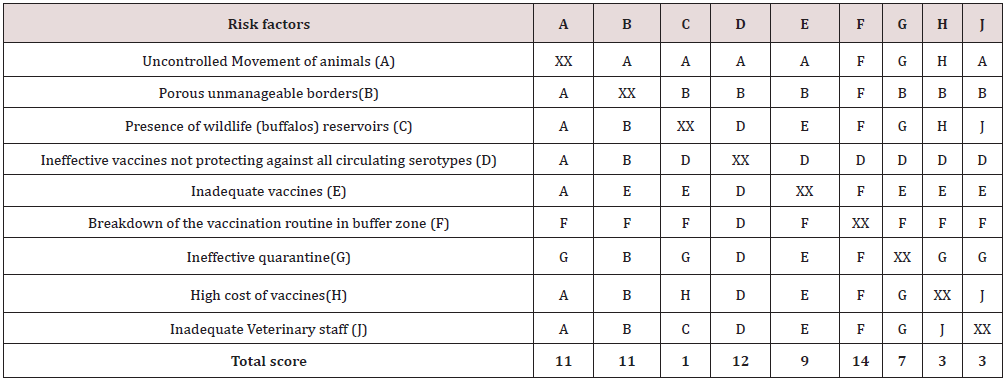

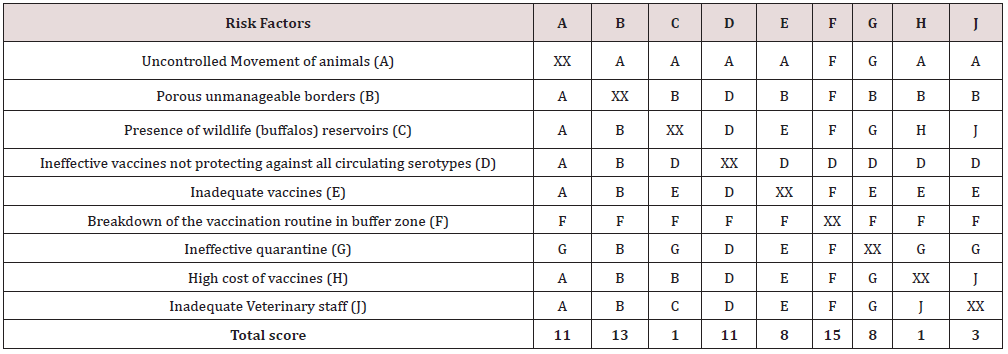

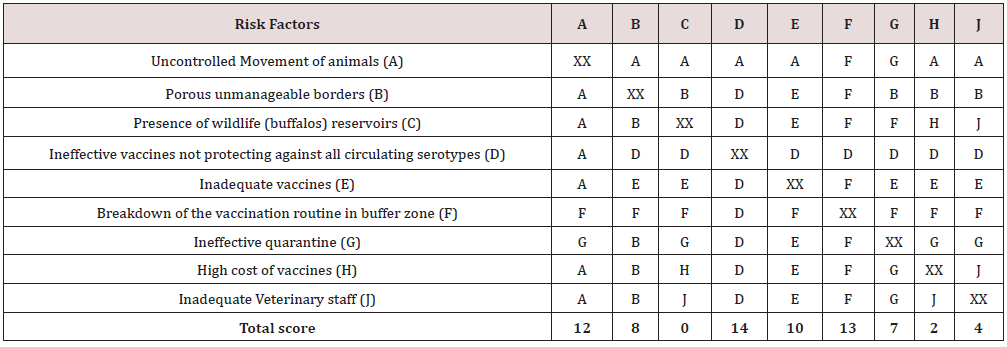

FMD-related mortality in calves as per perceptions of livestock keepers, using proportional piling

A high FMD-related mortality rate (48%) of calves was estimated by livestock keepers across the subcounties. It ranged from 44% in Kakuto Subcounty, to 45% in Kyebe and Kabira subcounties, 52% in Mutukula Town Council and 55% in Kasensero Subcounty (Figure 1). Risk factors associated with FMD outbreaks as per perceptions of livestock keepers, using pairwise ranking A summary of scoring and ranking of risk factors associated with FMD outbreaks in Kyotera district is shown in Table 3. Breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone (Mean Score 14.0, 95% CL (13.98 - 14.02); (2) Ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (Mean Score 12.4, 95% CL (12.36 - 12.44); (3) Uncontrolled movement of animals (Mean Score 10.8, 95% CL (10.75 - 10.85); (4) Porous unmanageable borders (Mean Score 10.4, 95% CL (10.34 - 10.46); (5) Inadequate vaccines (Mean Score 9.2, 95% CL (9.18 - 9.22); (6) Ineffective quarantine (Mean Score 7.6, 95% CL (7.58 -7.62) ; (7) Inadequate veterinary staff (Mean Score 3.8, 9.5% CL (3.76 -3.84); (8) High cost of vaccines (Mean Score 2.2, 95% CL (2.16 - 2.24 ); and (9) Presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Mean Score 0.6, 95% CL (0.58 – 0.62). were considered least important.

Figure 1: FMD-related mortality of calves per Subcounty in Kyotera district according to the perceptions of livestock keepers.

Table 3: A summary of risk factors associated with FMD outbreaks in Kyotera district and their ranking as per perceptions of livestock keepers, using pairwise ranking.

Table 3a presents the pairwise ranking of risk factors by livestock keepers in Kakuto Subcounty. Among others, breakdown of the vaccination routine in buffer zone (Score 14) and ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (score 14) had the highest rank, followed by inadequate vaccines (score 10), uncontrolled movement of animals (score 8) and porous unmanageable borders (score 8). Unfortunately, livestock keepers did not consider presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Score 0) as an important risk factor. In Table 3b is shown the pairwise ranking of risk factors by livestock keepers in Mutukula Town Council. Among others, breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone (Score 14) was considered highest ranked, followed by uncontrolled movement of animals (Score 12), porous unmanageable borders (Score 12), and ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (Score 11). Presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Score 1) and high cost of vaccines (Score 1) were considered by livestock keepers as least important risk factors.

Pairwise ranking of risk factors by livestock keepers in Kasensero Subcounty is displayed in Table 3c. Among others, breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone (Score 14) was considered the highest ranked, followed by ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (Score 12), then uncontrolled movement of animals (Score 11) and porous unmanageable borders (Score 11). Similarly, presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Score 1) was considered a least important risk factor by livestock keepers. Table 3d is showing pairwise ranking of risk factors by livestock keepers in Kyebe Subcounty. Among others, breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone (Score 15) was considered the highest ranked risk factor, followed by porous unmanageable borders (Score 13), the uncontrolled movement of animals (Score 11) and ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (Score 11). Presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Score 1) and high cost of vaccines (Score 1) were equally considered least important risk factors. Pairwise ranking of risk factors by livestock keepers in Kabira Subcounty is displayed in Table 3e. Among others, ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes (Score 14) was considered highest ranked, followed by breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone (Score 13), the uncontrolled movement of animals (Score 12) and inadequate vaccines (Score 10). Presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs (Score 0) was considered least important.

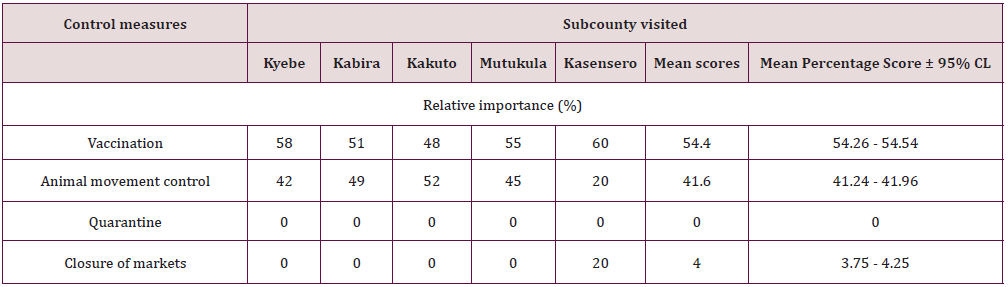

Relative importance of FMD control measures as per perceptions of Keepers

keepers identified vaccination, animal movement control, quarantine and closure of markets as major ways of controlling FMD in Kyotera district. In Table 4 is presented the relative importance of control measures across subcounties visited. Vaccination had the highest score (Mean score 54.40%, 95% CL (54.26 - 54.54), followed by animal movement control (Mean Score 41.60%, 95%CL (41.24 - 41.96)) and lastly closure of markets (Mean Score 4.00%, 95% CL (3.75 - 4.25)). Quarantine with a mean score of 0% was considered by livestock keepers a less important control measure.

Table 4: Relative importance (percentage) of control measures in different subcounties of Kyotera District as per perceptions of livestock keepers, using proportional piling.

The trend of FMD outbreak as per perceptions of the livestock keepers

To understand the trends of occurrence of FMD outbreaks in Kyotera district, livestock keepers were interviewed regarding the occurrence of outbreaks over the last 10 years (2009-2019) (Figure 2) and seasonal occurrence (Figure 3). In all subcounties visited, livestock keepers stated that FMD outbreaks had been experienced in Kyotera District in the last 1 to 5 years. Most livestock keepers recalled only the FMD outbreaks of 2016 which affected almost all the subcounties. Regarding seasonal occurrence of FMD outbreaks, most respondents across subcounties revealed that most FMD outbreaks are experienced during the dry seasons, especially June to September. Few outbreaks occur during wet season, March to May or October to December.

Figure 2: Trend of FMD outbreaks in subcounties over a period of 10 years as perceptions of livestock keepers.

Figure 3: Seasonal distribution of FMD outbreaks in Kyotera district as per the perceptions of Livestock keepers.

Identification of the FMD epicentre or its origin and how it spreads

Mapping by livestock keepers interviewed in Kabira, Kyebe, Kakuto, Kasensero and Mutukula subcounties regarding the epicenter or origin of FMD outbreaks is presented in Figures 4a,4b, 4c, 4d and 4e. Livestock keepers in Kabira Subcounty depicted free movement of animals from Rakai District and from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve, across the Uganda-Tanzania border into Kyotera District as the origin of FMD outbreaks (Figure 4a). Meanwhile livestock keepers from Kyebe Subcounty depicted free movement of animals from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve across the Uganda-Tanzania border into Kyotera District as the main origin of FMD outbreak (Figure 4b).

According to livestock keepers from Kakuto Subcounty (Figure 4c), the origin of FMD outbreaks was attributed to free movement of animals from (i) Isingiro district through Rakai district into Kyotera district or (ii) from Lyatonde and Kiruhura districts especially around the Lake Mburo National Park through Rakai District to Kyotera District or (iii) from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve in Tanzania into Kyotera District. Livestock keepers of Kasensero Subcounty mainly attributed the FMD outbreaks to free movement of animals from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve across the Uganda-Tanzania border into Kyotera District (Figure 4d). Meanwhile, livestock keepers from Mutukula Town Council attributed the origin of the FMD outbreaks to free movement of animals from either (i) Lyatonde District around the Lake Mburo National Park into Rakai, Isingiro and Kyotera districts or (ii) into Tanzania, Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve and back into Kyotera District in Uganda (Figure 4e). The main entry point of animals into Kyotera district from Isingiro, Rakai and Lyatonde district or from Tanzania across the border is through Koza Triangle as depicted in all maps (Figures 4a, 4b, 4c, 4d and 4e).

Figure 4: Mapping the epicentre or origin of FMD outbreaks in Kyotera district as per perceptions of livestock keepers in Kabira Subcounty (Figure 4a), Kyebe Subcounty (Figure 4b), Kakuto Subcounty (Figure 4c), Kasensero Town Council (Figure 4d) and Mutukula Town Council (Figure 4e).

Discussion

We report on a Participatory Disease Search that was conducted in Kyotera District. Its main aims were to understand trends in FMD outbreaks over the last ten years (2009-2019), associated risk factors and the epicenter or origin responsible for persistence of FMD outbreaks along the Uganda-Tanzania border. The study ably employed a variety of PDS tools according to Catley & Berhanu and CAHO[6,7]. Key informant interviews successfully helped unearth information from livestock experts on trends, risk factors, proven control measures and the epicenter or origin of FMD outbreaks. Likewise, focus group discussions helped livestock keepers recall information on trends, risk factors, proven control measures and the epicenter or origin of FMD outbreaks. The number of people per focus group lay within the recommended range of 8-13 participants (Catley & Berhanu, CAHO [6,7]). Ranking was successfully employed in pairwise ranking of risk factors, proportional piling of common diseases, FMD clinical signs and FMD-related mortality of calves. Visualization was successfully employed in mapping the epicenter or origin of FMD outbreaks, timelines for trends of outbreaks and a seasonal calendar for occurrence of FMD outbreaks.

Tick-borne diseases, Foot and Mouth Disease, Helminthosis, Lumpy skin disease, Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (CBPP), Ephemeral fever, Anthrax and Blackquarter were common diseases identified by focus groups. Foot and Mouth Disease emerged the most important disease across the subcounties. In line with these findings, FMD has been reported to be the most important disease associated with enormous widespread occurrence in Uganda (Rutebarika, [4]). Livestock keepers across the subcounties recognized wounds, death of calves and lameness as key clinical signs of FMD. Meanwhile, fever, salivation, loss of appetite and abortion were considered minor clinical signs. Despite limited awareness on some of the signs of FMD among livestock keepers, all these are conventional clinical signs for FMD (Queensland Government, [8]). The FMD-related mortality rate among calves was estimated to be high (48%) across the subcounties visited. Young animals or calves suffering from FMD are known to die from viral myocarditis (Queensland Government, [8]).

Regarding trends of FMD outbreak over the last 10 years (2009- 2019), Kyotera district had had the last FMD outbreak in 2016 which spread to all sub counties. The outbreak was very severe to the extent that some of the vaccinated herds came down with the disease. FMD vaccines used then were not able to quell the outbreak due to none response. Improper vaccines are a common feature with FMD control. SAT 1, SAT 2, and O are major serotypes circulating in Uganda, however there is no cross protection among each other (Rutebarika, [4]). Characterization of viruses in outbreaks and matching FMD vaccine batches with field serotype/ strains is recommended for tracing and instituting appropriate control measures (Rutebarika, [4]; AU-IBAR, [9]).

Livestock keepers across subcounties visited confirmed that FMD outbreaks had been experienced in the last 1-5 years. Seasonal occurrence of FMD outbreaks is mainly during dry seasons, especially in the month of June to September. Outbreaks are rare during wet seasons: March to May or October to December. The modes of spread of the FMD virus, that include, aerosol, contaminated vehicles, equipment/formites, other body fluids (Rutebarika, [4]) are adversely minimized during wet season yet facilitated during the dry season.

With little variations between subcounties, and concurrence between key informants and focus groups, major risk factors included (1) Breakdown of the vaccination routine in the buffer zone; (2) Ineffective vaccines not protecting against all circulating serotypes; (3) uncontrolled movement of animals; (4) Porous unmanageable borders ; (5) Inadequate vaccines; (6) Ineffective quarantine ; (7) Inadequate veterinary staff; (8) High cost of vaccines; and (9) Presence of wildlife (buffalos) reservoirs. This is in agreement with earlier reports in Uganda on FMD risk factors (Rutebarika, [4]).

The epicenter or origin of FMD outbreaks to Kyotera district was Koza Triangle, a border village where boundaries of districts of Kyotera, Rakai, Isingiro and Tanzania meet. Free movement of livestock from grazing areas in districts adjacent Lake Mburo National Game Park, such as Lyatonde, Rakai and Isingiro and from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve in Tanzania to Kyotera district through Koza Triangle resulted into spread of FMD to Kyotera district. Putting this in perspective, 80% of Uganda’s livestock is raised extensively, grazing and watering communally and moving long distances in search of pasture and water especially during prolonged dry periods (Rutebarika, [4]). Close contact associated with availability of water and feed especially in pastoral production systems particularly during drought periods when animals congregate at the limited pasture and watering points increases the risk of FMD transmission (Rutebarika, 4]; AU-IBAR, [9]). Mapping by livestock keepers in different subcounties visited confirmed the fact that, the origin of FMD outbreaks was attributed to free movement of animals from (i) Isingiro district through Rakai district into Kyotera district or (ii) from Lyatonde and Kiruhura districts especially around the Lake Mburo National Park through Rakai District to Kyotera District or (iii) from Maramagambo Forest Game Reserve across the Uganda-Tanzania border into Kyotera District. Animal movement and wildlife reservoirs are important for transmission of FMD in the region (AU-IBAR, 2014). Existence of susceptible wildlife which act as reservoirs for the FMD virus that easily mix with domestic animals (Rutebarika, [4]), especially when livestock are grazing in wildlife reserves increases the risk of FMD transmission.

Livestock keepers identified vaccination, animal movement control, quarantine and closure of markets as major ways of controlling FMD in Kyotera district, with vaccination, animal movement control, and closure of markets considered the most important. In line with this, FMD control in Uganda is undertaken through a multi-disciplinary approach consisting of early detection and reporting; movement control; quarantine restrictions; vaccination with trivalent vaccine (covering the most common outbreak serotypes–SAT 1, SAT 2, and O); combined with serological and molecular confirmations (Rutebarika, [4]).

Expert advice and recommendations from key informants highlighted the following control measures as most effective:

• Containing FMD outbreaks through buffer vaccination targeting the border subcounties and Koza Triangle

• Involvement of communities and livestock owners in FMD surveillance and control

• Maintaining of livestock Check Points while involving the Internal Security Organization, Police and Local Councils in controlling of livestock movement

• Existence of a Memorandum of Understanding between Uganda and Tanzania to strengthen collaboration and harmonization of control of Transboundary Animal Diseases, especially FMD along the Uganda –Tanzania border areas

• Cross-border collaboration and its probable strengthening through a cross-border project between Uganda and Tanzania Governments for control of Transboundary Animal Diseases along the Uganda-Tanzania border

• Limiting the period of time for implementation of movement control through quarantines to avoid economic effects associated with livestock market closures in the district

• Securing of FMD vaccines from Government (controlled source) rather than procuring from private sector (uncontrolled source) appears to be a more effective strategy for FMD control. Government sources of vaccines involve either vaccine matching with field serotypes (AU-IBAR, 2014) or provide trivalent vaccines containing circulating FMD serotypes (Rutebarika, [4]).

In conclusion, vaccination, animal movement control, and closure of markets were considered the most important control measures for FMD. Buffer vaccination targeting the border subcounties and Koza Triangle was the most effective approach for containing FMD outbreaks [10].

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Edward Kimbugwe, Dr John Mary Lutaaya and Mr. Vincent Jjumba for their cooperation and support during field implementation of the study in Kyotera District. In addition, greatly indebted to Dr Anna Rose Ademun Okurut, The Commissioner Animal Health, in the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries for her support to the study. We appreciate the guidance and input offered by Dr Joseph W. Magona, the FAO PDS/ PE Consultant Mentor. In the same vein, we are grateful to Dr Sam Okuthe, the Uganda Country Team Leader, ECTAD for his technical guidance to the study. The technical and financial support by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations in Uganda is highly appreciated.

References

- African Union Interafrican Bureau of Animal Resources (2010) Framework for Mainstreaming Livestock in the CAADP Pillars,.

- Kitching PR, Hammond J, Jeggo M, Charleston B, Paton D, et al. (2007) Global FMD control – Is it an option? Vaccine 25(30): 5660-5664.

- Paaryb (2014) Pan African Animal Resources Year Book paaryb_20160203_2014_en.pdf

- Rutebarika (2012) Foot And Mouth Disease In Uganda: Situation analysis in Uganda Spatial distribution and trends. At the Global Foot-and-Mouth Disease Research Alliance meeting 17thto 19thApril 2012 Hazy-view, Kruger National Park South Africa.

- Baluka SA, Ocaido M, Mugisha A (2014) Prevalence and economic importance of Foot and Mouth disease, and Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia Outbreaks in cattle in Isingiro and Nakasongola Districts of Uganda 2(4): 107-117.

- Catley A, Berhanu A (2003) Using Participatory Epidemiology to Assess the Impact of Livestock Diseases. FAO-OIE-AU/IBAR-IAEA Consultative Group Meeting on Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia in Africa 12-14 November 2003, FAO Headquarters, Rome, Italy.

- CAHO (2011) A manual for practitioners in community - based animal health outreach (CAHO) for highly pathogenic avian influenza.

- Queenland Government (2019): Clinical signs of Foot and Mouth Disease.

- AU-IBAR (2014) Standard Methods and Procedures (SMPs) for Control of Foot and Mouth Disease in the Greater Horn of Africa. Nairobi

- FAO (2005) Livestock Sector Brief. Lao Peoples Democratic Republic. FAO, Rome, Italy.

.png)

.jpg)