Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4692

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4692)

Dental Caries Experience Amongst 3-15 Year Old Children with Heart Disease Attending Paediatric Cardiology Clinics in Nairobi Kenya Volume 1 - Issue 3

Daniel Kimei, Gladys N Opinya* and Arthur M Kemoli

- Department of Paediatric Dentistry & Orthodontics, University of Nairobi, Kenya

Received: February 12, 2018; Published: February 21, 2018

*Corresponding author: Gladys Nabubwaya Opinya, Department of Paediatric Dentistry &Orthodontics, University of Nairobi, Kenya

DOI: 10.32474/MADOHC.2018.01.000114

Abstract

Introduction: Children with a medical disability are those whose medical condition puts their general health further at risk if they suffer dental disease. Because of this risk to health, or even to life, their dental care is of vital importance.

Objective: The objective of the study was to determine the oral health status of children suffering from different types of heat ailments.

Design: The study was a cross-sectional descriptive study, and it was conducted in three paediatric cardiology clinics. The clinic at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Gertrude’s Garden Children's Hospital and Mater Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. A total of 81 children were examined, and their mean age of the children was 8.16±2.81 years; males were 44(54.3%) while females were 37(45.7%). The prevalence of dental caries in the deciduous teeth was 65.57%, and in permanent teeth, it was 40%. The mean dmft was 2.85±3.45. The oral hygiene status was poor with mean plaque score of 1.72±0.59 (n=81) with the majority of the children having fair oral hygiene 37(45.7%) and poor oral hygiene 36(44.4%).

Conclusion: The mean dmft of the children examined was 2.85 (±3.45 SD) which reflected unmet treatment needs among these children. Also, these carious teeth acted as loci for the dislodgement of bacteria into the bloodstream during mastication or tooth brushing, and this increased the risk of the child developing sun acute bacterial endocarditis. The children with poor oral hygiene were at risk of bacteraemia and development of subacute bacterial endocarditis and development of new carious lesions.

Keywords: Caries; Children; Cardiac diseases

Introduction

Heart diseases can be congenital or acquired [1]. Congenital heart defects can be due to an aberrant embryonic development of a normal structure with failure to progress beyond an early stage of embryonic development [1]. Congenital heart disease can be further classified as cyanotic or acyanotic. Acquired heart diseases are those conditions that occur at any age after birth [1]. They include rheumatic fever and infective bacterial endocarditis. Congenital Heart Disease occurs in about 1% live births. The incidence is higher in stillborn (3-4%) and about (10-25%). Congenital cardiac defects have a wide spectrum of severity in infants. With advances in both palliative and corrective surgery, the number of children with congenital heart defects surviving to adulthood has increased dramatically [1]. In the developing countries, the annual incidence of acute rheumatic fever is currently as high as 282 per 100,000 population. Worldwide, rheumatic heart disease remains the most common form of acquired valvular heart disease in all age groups. The disease accounts for as much as 50% of all cardiac admissions in many hospitals [1,2].

There has been a decline in the incidence of rheumatic heart disease in industrialised countries since the introduction of antibiotics. Also, there have been improvements in living conditions with a reduction in crowding, poverty which contributes to the spread of group A streptococcal infections. The incidence of both initial attacks and recurrences of Rheumatic fever peaks in children aged 5-15 years, the age of greatest risk for the group a streptococcal pharyngitis [1]. Diagnostic advances, neonatal care, and surgical interventions have increased the survival rate of children with heart defects and those that develop acquired heart diseases1. With this increase in survival comes an increased burden of complexity when managing these children's oral health and disease [3]. The importance of achieving and maintaining oral health for individuals with heart disease has been highlighted recently by much debate around changes in guidelines relating to prophylaxis against infective endocarditis [4,5].

Regardless of which guidelines are in use, one thing has not changed: the dental team is charged with guiding the child with heart disease towards enjoying a lifetime of optimum oral health. The highest risk of developing the dental disease is seen in children from low-income or under-represented minority families, and in those with special health care [6,7]. According to the Kenya National Oral Health policy document, the dmft value for Kenyan 5- year old children as at 2002 was 1.5±2.2, while 43% of 6-8-year-old children had caries [8]. The prevalence of dental caries in Kenyan urban and rural 12-13-year-old children in 1996 was found to have been 27% (DMFT=0.71) respectively. The urban children were from a population surrounding Nairobi [9]. The American Heart Association recognises that achieving and maintaining good oral health may reduce the incidence of some cardiac abnormalities, such as infective endocarditis [7]. Its guidelines published in 2007 recommend dental evaluations and treatment before cardiac valvular surgery, or repair of congenital disabilities to decrease the risk of infective endocarditis [10].

Although there is a scarcity of information available in the literature on the oral health of children with heart disease, some studies have reported that these children suffer poorer oral health when compared to a control group [11]. There are several reasons for this: chronic intake of sugared medicines [12,13]; increased tooth susceptibility from developmental enamel defects [11]; greater consumption of sweets in compensation and negligence of oral hygiene as a result of a greater concern with the cardiac disease [14,15]. Children with heart conditions which often receive extensive medical and surgical treatment and have shorter or longer stays in hospitals during their first years of life [16,17]. The American Heart Association has recommended a high standard of oral health for patients with heart disease. However, studies on children at risk for infective endocarditis have reported poorer oral health compared that of healthy children [10]. Silva et al. [14] In Brazil found out that, 98% of the patients presented a visible plaque and 99% presented spontaneous or unprovoked bleeding in one or more examined surfaces.

Although dentists are expected to give priority to medically handicapped patients, yet a low frequency of regular dental care has been reported for children with heart defects compared to healthy groups [18,19]. Closer consultations between paediatric cardiologists and paediatric dentists could help improve dental care for the children suffering from cardiac disease. These close multidisciplinary management would enhance the prevention of the diseases and maintenance of excellent oral health. Children with severe disease should be referred to a paediatric dentist before they are one year old [20]. An individual treatment plan to maintain oral health, based on risk assessment, should be established for all children with cardiac disease [21]. The focus should be on caries prevention and include dietary counselling, oral hygiene, and fluoride supplements if necessary. The demanding situation for the parents and families of the patients with cardiac disease should be acknowledged and understood [21]. The dental caries experience and the oral hygiene status among these children in Kenya and other developing countries have not been extensively investigated.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. All the patients and their caregivers aged 3 to 12 years attending paediatric cardiology clinics at the selected hospitals; Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), Gertrude's Garden Children's Hospital (GGCH) and Mater Hospital were enrolled in the in the study. A Semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the child and the parent/guardian; knowledge, attitudes and practices on preventive oral healthcare.

Sampling Method and Sample Size

Purposive sampling was used to select study hospitals. The KNH, the Mater Hospital and GGCH were selected from the hospitals offering cardiology services due to the considerable large number of patients seeking treatment at these institutions. All the patients aged 3 to 12 years attending paediatric cardiology clinics at the selected hospitals during October and November 2008 were eligible for the study. To calculate the sample sizes the study for Balmer et al [1]. in which they had reported a prevalence 58% in children suffering from cardiac disease was used. The following formula was being used to determine the sample size for this study: - N=Z2 P (1-P)/d2, and where N= the desired sample size (where population >10,000) while, P= reported the prevalence of untreated and treated dental problems among children with heart disease. And Z= standard normal deviate, usually set at 1.96 corresponding to 95% confidence level where D=degree of precision, usually set at 0.05; and N= 1.96X1.96X0.58 (1-0.58)/ 0.05 X 005 N= 375.

For a population < 10,000; NF= N =1+N/n Where 100 is the average number of total patients recorded in the clinic attendance registers at the selected hospitals within three months, therefore; 374/ 1+374/100 = calculated sample size of 79 cases But 81 patients were recruited for the study. Clinical examinations were done to record the oral health status among the children as they waited to consult the cardiologist. The examination was conducted under natural light using sterilised instruments with participants seated on a chair next to a window. Care was taken during the examination that probing instruments were not used so as not to cause septicaemia as the children were not on prophylactic antibiotics hence, periodontal probing for gingivitis was not done. Predesigned questionnaire sheets were used to score for dental caries and plaque. The presence of caries presence was determined in all the deciduous teeth and recorded as dmft while in the permanent present caries experience was recorded as DMFT Dental plaque was recorded based on the Loe and silness (1964) plaque score index.

Calibration

a. Data Validity and Variability

Before commencement of the study, calibration was done by one of the supervisors at the Department of Paediatric Dentistry, and Orthodontics, School of Dental Sciences and repeated also in the field. The use of a structured questionnaire and standard examination procedure was employed for all participants. All the data collection tools were pre-tested before being used. The supervisors calibrated the investigator and a Cohen's kappa index score of 0.87 and 0.85 (n=10) was obtained for dental caries and plaque score respectively. A duplicate clinical examination was performed on every 7th subject and Cohen's kappa index score of 0.91 and 0.86 (n=12) was obtained for dental caries and plaque score which showed good consistency.

b. Data Analysis

Data was coded and analysed using SPSS version 17 software from SPSS Inc. IL. And presented as descriptive format, The Chi- square and Pearson correlation tests were used to determine the test of statistical significance.

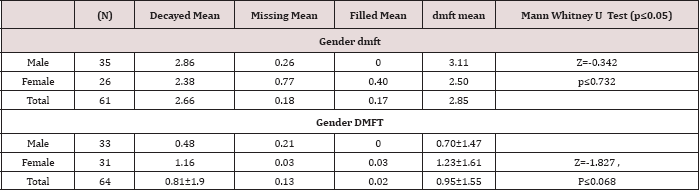

Table 1: Distribution of dmft/DMFT about the gender of the chil

Results

A total of eighty-one children were recruited into the study with 44 (54.3%) being males and 37 (45.7%) were females. Their ages ranged between 3-12 years with a mean age of 8.16 years (± 2.81 SD). The males were younger with a mean age of 7.93 years (± 2.79 SD) compared to the females who had a mean age of 8.72 years (±2.59 SD), but the difference was not statistically significant). However, when the study population was grouped into by age the 6-9-year-olds were 33 (40.7%), and 3-5 year-olds were 16(19.8%). As concerns the groups about age and gender there was no statistically significant difference with Pearson Chi χ2 =1.287, two df, p=0.525(p≤0.05). The children were distributed according to the type of heart disease, RHD accounted for 36(44.5%) while infective endocarditis were 4(4.9%) as shown in Tables 1 & 2. The duration since diagnosis of the cardiopathy ranged from less than one year to 12 years with a mean duration of 3.53±3.43 years.

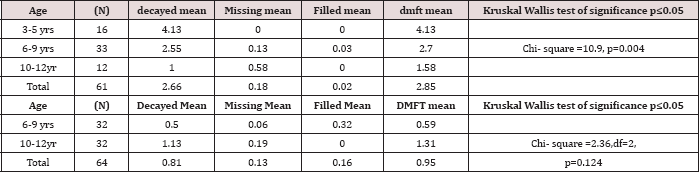

Table 2: Distribution of dmft/DMFT according to children's age.

Nearly half of the children, 40(49%) had been diagnosed with the disease for a duration of between 1 to 5 years, while those who had been diagnosed more than five years and those less than one year accounted for 30% and 21% respectively (Table 1). Out of the 81 children, 37(46%) were from rural areas, 28(34%) were from Nairobi, and 16(20%) were from other urban centres other than Nairobi. A total of 81 children were examined for dental caries; out of which 61 children who had deciduous teeth, 40(65.57%) were found to have dental caries. The mean dmft of the 61 children examined was 2.85 (±3.45 SD). The mean decayed, missing, and filled deciduous teeth among the 61 children with deciduous teeth was d=2.65±3.37; m=0.18 and f=0.17 respectively. The total number of deciduous teeth examined was 839. Out of these, untreated dental caries was observed in 227 (27.05%), and teeth missing due to dental caries accounted for 28 (2.5%) while filled teeth were only one (0.1%). The number of sound deciduous teeth was 590, accounting for 70.3%.

Caries experience recorded as dmft was present among 16(19.8%) 3-5-year olds; 21(25.9%) among 6-9-year olds and 7(4.4%). The caries experience dmft in the 10-12-year old age group had a χ2=0.963, d.f 2 and p=0.618 (p≤0.05) which was not statistically significant. The males had a higher dmft of 3.11±3.93 (n=35), compared to a dmft of 2.5±2.71 (n=26) among the females, with p=0.732 (p≤0.05). Dental caries experience in deciduous teeth decreased significantly with age among 3-5; 6-9 and 10-12-year- olds as shown in Tables 3 & 4 with a Chi-square =10.9, p=0.004 (p≤0.05) (Table 2). There were 64 (78%) children out of 81 who had permanent dentition and out of the 64 caries was found to be present in 23 (28.4%).

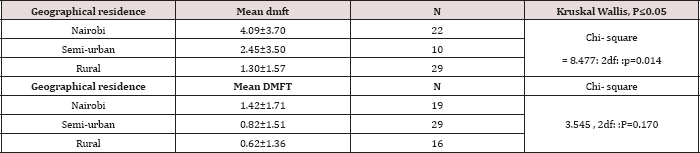

In the permanent teeth, the total number of teeth examined was 1113, out of which decayed teeth were 79 (7.1%); teeth missing due to dental caries were 21 (2.5%) while filled teeth were 8 (0.7%) and sound permanent teeth were 1024 (92%). The mean DMFT in 64 children was 0.95±1.55 with mean Decayed, Missing, and Filled permanent teeth being D=0.81±1.39; M=0.13; and F=0.02 respectively. In the permanent dentition, females had higher DMFT of 1.23±1.86 compared to a DMFT of 0.69±1.47 among the male with p=0.068 (p≤0.05) (Table 2). In the permanent dentition, though there was no statistical difference in DMFT about age with a X2=2.36 2df p=0.124 (p≤0.05), the mean DMFT increased with age among the 6-9-year and the 10-12-year olds as illustrated in Table 2. The mean dmft varied significantly about the child’s residence in the last two years as illustrated in Table 2. Children from Nairobi had the highest mean dmft of 4.09±3.70 and the least mean dmft of 1.30±1.57 was found among children from rural areas with χ2 = 8.477: 2df::P=0.014(p≤0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of DMFT/ dmft according to area of residence.

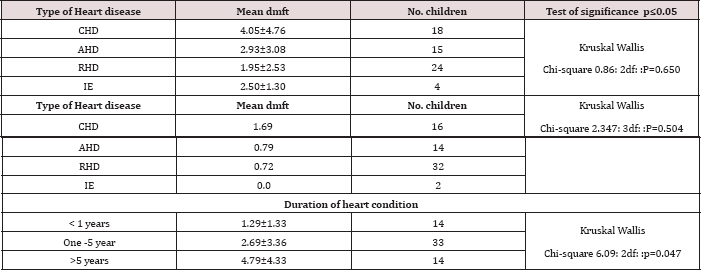

The mean DMFT also varied according to the area of residence, with children from Nairobi having highest DMFT of 1.42±1.71; and those from rural areas having least mean DMFT of 0.62±1.36, however, these were not statistically significant with ^2 =3.545: 2df: p=0.170 (p≤0.05). Table 4 illustrates that dental caries experience was highest among children with cyanotic heart diseases (CHD) with dmft of 4.05±4.76 and least among children with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) with dmft of 1.95±2.53 although these were not a statistically significant difference with p=0.650 (p≤0.05). In the permanent dentition, the mean DMFT was highest among the CHD group having DMFT 1.69±2.06, and Infective endocarditis (IE) had the least mean DMFT of 0, with P=0.504, (p≤0.05). The mean dmft increased with the duration since the heart disease was diagnosed. The children who had been diagnosed with the heart disease for a period more than five years had the highest dmft of 4.79±4.33 while the children who had been diagnosed in less than a year had the least dmft of 1.29±1.33. These differences were statistically significant with χ2 = 6.09: 2df: p=0.047(p≤0.05); Table 4. The same trend was also observed in the permanent dentition, with higher DMFT of 1.27±1.67 among those diagnosed for more than five years and lower DMFT of 0.60±1.40 for those diagnosed in less than one year (Table 4).

Table 4: Distribution of dmft/DMFT about the type of heart disease and the duration since diagnosis.

However this was not statistically different with χ2 = 2.879: 2df: p=0.237 (p≤0.05). Dental caries experience as was highest among the children whose caregivers were forty-one years or above in age with dmft of 3.07±4.4. However, the children whose caregivers were below 30 years and a low caries experience with a mean dmft of 2.79±2.79.There was no statistical significance between the caregiver's age and the dmft and DMFT with χ2 = 0.352: 2df:: p=0.84 (p≤0.05) for dmft and with χ2 = 1.332: 2df; p= 0.512 (p≤0.05) respectively; (Table 4). Caries experience about the level of education of the caregiver was not statistically significant. Children whose guardians had a primary level of education had a higher dmft of 3.14 while those who had no formal education had least dmft of 1.6 with χ2 = 1.74: 3df: p=0.627 and DMFT with χ2 = 0.654: 3df: p=0.884 (p≤0.05).

Figure 1: Distribution of oral hygiene status among the children.

Oral Hygiene of the Children

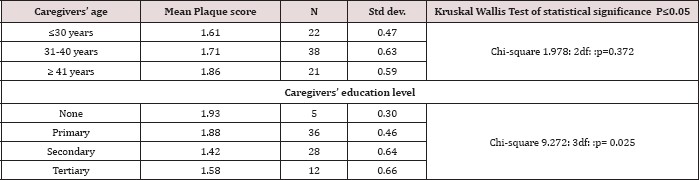

The children were examined for plaque based on love and silliness plaque index. The average plaque score was 1.72±0.59 and varied according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the child and the caregivers. The children were grouped according to the severity of plaque as per the Loe and Silness index. Majority of the children had fair oral hygiene 37(45.7%); and poor oral hygiene 36(44.4%) as illustrated in Figure 1. Male children had higher plaque scores of 1.76±0.58 compared to the females who had a plaque score of 1.68±0.60, although this was not statistically significant as illustrated in Table 5. The plaque score levels gradually reduced with the children's age with the 3-5-year-olds having highest plaque score of 1.85±0.42. However, these differences were not statistically significant with Kruskal Wallis χ2 = 2.768: 2df: p= 0.251 (p≤0.05). About the different heart disease, 33 children who had RHD had a higher plaque score of 1.82±0.56. However, there were no significant differences in the plaque scores among the children about the different heart disease.

Table 5: Distribution of plaque score about caregivers' characteristics.

The children who had been diagnosed with the heart disease for a period of between 1-5 years had higher plaque scores of 1.79±0.58 (Table 5) with Kruskal Wallis χ2 = 0.964: 2df::p= 0.617. About the area of residence, children from rural areas had the highest plaque score of 1.82±0.53 (Table 5). However, there was no significant relationship between the residence and the plaque score with Kruskal Wallis χ2 = 2.893: 2df:: p=0.617 (p≤0.05). The oral hygiene among the children was better among the children whose caregivers were below 30 years with a plaque as shown in 5. However there was no statistical difference with χ2 = 1.978: 2df: p= 0.372 (p≤0.05). As concerns the caregivers level of education, the children whose parents had secondary education had the least mean PS of 1.42±0.64; and those with no formal education had a higher plaque score of 1.93; χ2 = 9.272: 3df::p= 0.025, (p≤0.05).

Discussion

In this study, 81 children were examined for plaque and caries experience with the age range of 3 years to 12 years, with a mean of 8.16 years (± 2.81 SD). The age range in this study was similar to other studies [22] who examined children aged two to16 years, 12 months to 71 months-old; and examined 2-15-year-olds. The age range of 3-12 years was chosen as these were the children who were attending the paediatric cardiology units at the selected clinics, with those beyond this age bracket attending the general cardiology clinics together with the adults [23,24]. The boys to girls ratio for the children was approximately 1:1 which is similar to previous Kenyan studies by Ngatia et al. [25] and Njoroge et al. [26] who were looking at the oral health of normal pre-school children. This may be a reflection of the Kenyan population where the ratio of the male to female is approximately 1:1 as is reflected in the 2006 Kenya Bureau of Statistics report [27]. The same pattern has also been reported among the past studies by silva et al. and Fonseca et al. 2009 since heart diseases affect both male and females equally [23,14].

The children examined were suffering from various types of congenital and acquired heart diseases. This was an attempt to include all the types of heart diseases compared to most of the past studies that have been examined children with congenital heart diseases only [20-28]. The duration since diagnosis of the cardiopathy ranged from less than one year to 12 years with a mean duration of 3.53±3.43 years. Nearly half of the children, (40, and 49%) had been diagnosed with the disease for the duration of between 1 to 5 years, while those who had been diagnosed more than five years and those less than one year accounted for 30% and 21% respectively. The children who had been diagnosed for 1-5 years were more because they were awaiting surgeries or were undergoing post-operative reviews. This study did not establish if the caregiver who had accompanied the child on the examination day had been the one consistently accompanying the child. However it was noted that mothers were 44 (54%), fathers were 23 (28%) while guardians were 14 (18%).

Children accompanied by their mothers when seeking healthcare may also likely be supervised for oral healthcare by the mothers. The level of formal education among the caregivers who accompanied the child in this study was relatively low, with 36 (44%) having obtained the primary level of education. The highest level of attained education was secondary with twenty- eight 28 (35%) caregivers. The tertiary level of education had 12 (15%) and 5 (6%) had no formal education. This level of education is nearly similar to that reported by the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey [29] but lower than 51.2% of mothers and 49.1% of fathers having attained secondary education as found by [30]. The mean dmft and DMFT in this study was 2.85±3.45 and 0.95±1.55 respectively. The mean dmft values of 2.85±3.45observed in this study were high when compared to the national values of 1.87 for children aged 3-5 years. Studies in among "normal" school children in developing countries with dmft values which ranged between of 1.9 and 2.6 [23,31].

The mean plaque score in this study was 1.72±0.59, corresponding to fair oral hygiene. The proportion of children who had visible plaque was 98 % (n=80). These are similar to the findings by [14] who found a plaque to be present among 98% of the children examined. [11] Found higher plaque scores of 0.65±0.22, though different plaque index had been used to check for the presence or absence of plaque. Ober et al. [32] in their study on children with cerebral palsy found mean plaque score of 1.56±0.87. Other studies, though they have not mentioned the specific plaque scores, have reported higher plaque scores and poor oral hygiene among children with cardiac disease [17,22,24]. The high proportion of children with a visible plaque and the higher plaque scores among the children with heart disease is a trend of concern.

The high plaque scores put at risk for infective endocarditis should maintain a high standard of oral health [10]. Periodontal probing was not done because antibiotic prophylaxis had not been administered. However, it has been documented that gingivitis in childhood when not diagnosed and eliminated, follows the individual until adult life and may progress into periodontitis [15]. The differences in plaque scores about age and gender of the children could be because girls are more conscious of their appearance and therefore are more likely to clean their teeth thus having lower plaque scores than boys. However, the differences were not statistically significant. Similar findings have been reported by Musera et al. [33] and Owino et al. [34]. The improvement of oral hygiene with age of the child could be a reflection of the better plaque control among the older children who have better manual dexterity in brushing teeth compared to younger children who rely on the parents to clean their teeth. In the study, there were a high proportion of the children who had unsupervised brushing, and this may explain the high plaque score levels [35,36].

Though there were differences in the plaque scores relation to the duration since diagnosis, the different heart disease and the geographical residence within the last two years the lack of statistical significance may be due to the small sample sizes in each category. Alternatively, the difference could have been influenced by ease of access and use of toothbrushes and dentifrices for the urban children. The differences in plaque scores was observed as better oral hygiene among the Nairobi residents compared to those children from the rural areas. The influence of the level of education of the caregiver was significant, with higher plaque score of 1.93±0.30 being observed in children whose caregivers had no formal education. The plaque scores of 1.42±0.64 were observed in children whose caregivers had secondary school education; this could probably be because the caregivers were aware of the importance of oral hygiene care among these children and could also be because these caregiver's could afford to avail essential tooth cleaning aids resulting in better oral hygiene practices.

Conclusion

The prevalence dental caries in deciduous dentition was 65.57 % and 40% in the permanent teeth. The mean dmft of the children examined was 2.85 (±3.45 SD) which reflected unmet treatment needs among these children. The oral hygiene status was poor with mean plaque score of 1.72±0.59 (n=81) with the majority of the children having fair oral hygiene 37(45.7%) and poor oral hygiene 36(44.4%).This means that these children are at a risk of bacteraemia induced by normal physiological processes without necessarily any invasive dental procedures. Also, poor oral hygiene increases the likelihood of developing dental caries and periodontal diseases.

References

- Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF (2007) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. (18th edn); PA: Saunders, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 1953.

- Cowper TR (1996) Pharmacologic management of the patient with disorders of the cardiovascular system. Dental Clinics of North America 40(3): 611-647.

- Balmer R, Frances AB (2003) The experiences with oral health and dental prevention of children with congenital heart disease. Cardiology in the Young 13(5): 439-443.

- Fitzergerald K, Fleming P, Franklin O (2010) Dental management for children with congenital heart disease. Primary dental care 17(1): 2125.

- Bayliss R, Clarke C, Oakley C, W Somerville, AG Whitfield, et al. (1983) The microbiology and pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. British Heart Journal 50(6): 513-519.

- Moore RS, Hobsen P (1989) A classification of medically handicapping conditions and the health risks they present in the dental care of children. Cardiovascular, haematological respiratory disorders. Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2: 73-78.

- Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, Ann F Bolger, Arnold Bayer, et al. (1997) Prevention of bacterial endocarditis -recommendations by the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Dental Association 277: 1794-1801.

- Ministry of Health (2002) National Oral Health Policy and Strategic Plan. Government Printer. Nairobi.

- Dattani S, Hawley GM, Blinkhorn AS (1997) Prevalence of dental caries in 12-13-year-old Kenyan children in urban and rural areas. International Dental Journal 47: 355-357.

- American heart association guidelines (2007) downloaded December 2008.

- Hallett KB, Radford DJ, Seow WK (1992) Oral health of children with congenital cardiac diseases: a controlled study. Pediatric Dentistry 14(4): 224-230.

- Creighton JM (1992) Dental care for the pediatric cardiac patient. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association 58(3): 201-207.

- Maguire A, Evans DJ, Rugg Gunn AJ, Butler TM (1999) Evaluation of sugar-free medicines campaign in north-east England: quantitative analysis of medicine use. Community Dental Health 16(3): 131-137.

- Silva DB, Souza IPR, Cunha MC (2002) Knowledge, attitudes and status of oral health in children at risk for infective endocarditis. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12(2): 124-131.

- Franco E, Saunders CP, Roberts GJ, Suwanprasit A (1996) Dental disease, caries-related microflora and salivary IgA of children with severe congenital cardiac disease: an epidemiological and oral microbial survey. Paediatric Dentistry 18(3): 228-235.

- Gould MSE, Picton DCA (1960) The gingival condition of congenitally cyanotic endocarditis individuals. British Dental Journal 12: 96-100.

- Pollard MA, Curzon ME (1992) Dental health and salivary Streptococcus mutans levels in a group of children with heart defects. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2(2): 81-85.

- Balmer R, Bu Lock FA (2003) The experiences with oral health and dental prevention of children with congenital heart disease. Cardiology in the Young 13(5): 439-443.

- Lowry LY, Evans DJ, Lowry RJ, Welbury RR (1996) Under-registration for dental care of children with heart defects in the north-east of England: a comparative study. Primary Dental Care 3(2): 68-70.

- Saunders CP, Roberts GJ (1997) Dental attitudes, knowledge, and health practices of parents of children with congenital heart disease. Archives of Disease in Childhood 76(6): 539-540.

- Grindefjord M, Dahlia G, Nilsson B, M odeer T (1996) Stepwise prediction of dental caries in children up to 3.5 years of age. Caries Research 30(4): 256-266.

- Dmft WHO

- Loe and silness (1964) plaque score index.

- Berger ENH (1978) Attitudes and preventive dental health behaviour in children with the congenital cardiac disease. Australian Dental Journal 23(1): 87-90.

- Fonseca MA, Evans E, Teske D, Thikkurissy S, Amini H (2009) The impact of oral health on the quality of life of young patients with congenital heart disease. Cardiology in the Young 19(3): 252-256.

- Smith AJ, Adams D (1993) The dental status and attitudes of patients at risk of infective endocarditis. British Dental Journal 174(2): 59-64.

- Ngatia EM, Imungi JK, Muita JW, Nganga PM (2001) Dietary patterns and dental caries in nursery school children in Nairobi, Kenya. East African Medical Journal 78(12): 673-677.

- Njoroge NW (2007) Early childhood caries among 3-5-year-olds and their caregiver's oral health knowledge, attitude and practice in Kiambaa Division, MDS Thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

- Central Bureau of Statistics (1999) Kenya population and Housing census 1999.

- Stecksén Blicks C, Rydberg A, Nyman L, Asplund S, Svanberg C (2004) Dental caries experience in children with congenital heart disease: a case-control study. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 14(2): 94-100.

- Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (2003) The government printer.

- Gichu N, Opinya GO, Ngatia EN, Gathece LW (2009) Influence of parental anxiety on children's behaviour during dental treatment about the caries experience among 3-5-year-olds in three public dental clinics in Nairobi. MDS thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

- Holm AK (1990) Caries in the Pre-school Child: International Trends. Journal of Dentistry 18(6): 291-295.

- Ober AO, Opinya GO, Kemoli AM (2006) Oral health status and oral health service utilisation among children with cerebral palsy in Kenya. MDS thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

- Musera DK (2003) Dental Caries, gingivitis, oral health knowledge and practices among 10-12-year-old urban and rural children in Kenya. MDS Thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

- Owino RO, Masiga MA, Nganga PM, Macigo FM (2007) Dental caries and gingivitis among 12-year-old children in peri-urban Kitale, Trans-nzoia District. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...