Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Case Report(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Unusual Esophageal Foreign Bodies: A Case Involving A Glass Shard Volume 4 - Issue 1

Tall Hady1*, Ndour Ngor1, Ndiaye Ciré2, Maiga Souleymane2, Pilor Ndongo2, Sall Cheickh Ahmado2, Loum Birame3, Ndiaye Malick4 and Diallo Bay Karim3

- 1Department ENT Regional hospital of Saint Louis, Senegal

- 2Department ENT National University of Fann, Senegal

- 3Department ENT Regional Albert Royer, Dakar, Senegal

- 4Department ENT Regional Diamniadio, Senegal

Received: November 28, 2019; Published: December 12, 2019

Corresponding author: Tall Hady, Department ENT Regional hospital of Saint Louis, Senegal

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2019.04.000179

Abstract

The ingestion of a foreign body is most often accidental in children. We report the case of a 9-year-old child, without any particular prior history of disease, who was admitted to the emergency ward of the ENT and cervicofacial surgery unit at the Regional Hospital Center of Saint Louis (Senegal) for accidental ingestion of an object during a meal (breakfast). The clinical examination found hypersalivation. Lateral cervical radiography revealed the presence of a radiopaque foreign body. Extraction of the glass shard-like foreign body was performed by endoscopy under general anesthesia. The post-operative management was straightforward.

Keywords: Foreign body; child, esophagus, endoscopy

Introduction

The ingestion of a foreign body (FB) is a relatively frequent domestic accident in children [1,2]. These esophageal foreign bodies are diverse in nature and they tend to be coins in children [2,3]. Aside from the commonly encountered types of foreign bodies, rare cases have been described in the literature [1,3-5], with some unusual findings at times. We report a case involving a glass shard-like esophageal foreign body in a boy of 9 years of age.

Observation

This case involved a 9-year-old schoolboy, with no particular prior history of disease, who was admitted to the emergency ward at the ENT unit of the Regional Hospital Center of Saint Louis (Senegal) for a suspected esophageal foreign body. Questioning of the parents revealed accidental ingestion of a glass shard-like foreign body during a meal (breakfast). The accident occurred on 8 July 2019 at approximately 12 pm. The symptomatology comprised hypersalivation, without signs of associated nausea and vomiting nor foreign body aspiration.

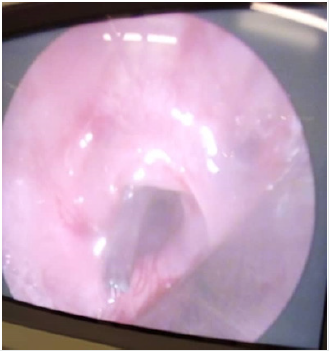

At admission, the examination found hypersalivation. The rest of the ENT examination was unremarkable. The pleuro-pulmonary examination found the patient to be apneic, and the auscultation was without anomaly. The lateral cervical radiography revealed an esophageal foreign body at the C6-C7 level that was radiopaque and that had a linear shape (Figure 1). The esophagoscopy under general anesthesia (Figure 2) found a glass shard-like foreign body (Figure 3) at the level of the Killian mouth. The extraction was performed using forceps for foreign objects. The endoscopic inspection was unremarkable, without signs of lesion of the esophageal mucosa (Figure 4). The post-operative management was straightforward.

Discussion

The ingestion of foreign bodies tends to be a domestic

accident, typically involving young children [1,6,7]. In 80% of

cases, these incidents occur before the age of 2 years, with a peak

in the frequency situated between 6 months and 3 years (70%

versus 30% between 3 years and 12 years of age) [2,7,8]. Various

types of foreign bodies are encountered, but coins are the most

frequent [2,3]. In case of an underlying pathological esophagus,

food items can be a cause [8,9]. It is, however, rare to encounter a

non-vegetal foreign body such as a shard of glass during a meal, as

was the case here. A degree of carelessness or a lack of attention

by those preparing the meal could have been responsible for this

accident. The clinical symptoms are often hard to interpret, and

the diagnosis is assisted by those accompanying the child and the

complications that confirm the presence of the foreign body. The

clinical manifestations tend to correlate with the age of the child,

the nature and the size of the object, and the time since the foreign

entity was ingested.

It can involve hypersalivation that can be striped with blood,

nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, and dyspnea by compression of the

airways, or a cough [2,3,7,8]. Complications such as esophageal

perforations with a risk of displacement of the foreign body,

mediastinitis, a retropharyngeal abscess, a tracheoesophageal

fistula, or ulceration of the esophageal mucosa [6,9] were a concern

in this observation. Lateral cervical radiography most often allows

a diagnosis to be made in case of radiopaque foreign bodies, as in

our case. The diagnosis can be more difficult, however, with radiotransparent

foreign bodies. In these cases, upper gastrointestinal

series and diagnostic endoscopy remain the key to making a

diagnosis [3,7,8,10]. Accidental ingestions of foreign bodies most

often go unnoticed and 80 to 90% of these esophageal foreign

bodies are transported spontaneously to the stomach. Only 10

to 20% of them require extraction by endoscopy under general

anesthesia [7,8]. For our patient, the extraction was by endoscopy

under general anesthesia, without the occurrence of complications.

Conclusion

Glass shard-like esophageal foreign bodies are generally rare. They can be dangerous, however, due to the potential for complications, whence the need for early and prudent endoscopic extraction. Informing and making parents aware of this danger is the best strategy for prevention.

References

- Pegbessou E, Diom ES, Gueye O (2012) Body hugging oesogastric unusual in an infant. Med Black Africa 59(7): 386-388.

- Lakdhar-Idrissi M, Hida M (2011) Ingestion of foreign objects in children: about 105 cases. Arch pediatr 18(8): 856-862.

- Chouaib N, Rafai M, Belyamani (2013) Respiratory distress revealing a little-known esophageal foreign body. Rev Pneumol Clin.

- Chadha SK, Gopalakrishnan S, Gopinath N (2003) An unusual sharp foreign body in the oesophagus its Removal. Otolangol Head Neck Surg 128: 766-768.

- Cress CM, Moleski SM, Patel AK, Fenkel JM, Infantolino A (2010) The man who swallowed a table knife: A Case Repot. Dig Dis Sci 55: 3005-3006.

- Kaboré A, Sanou M, Nagalo K (2019) Complications of foreign bodies with batteries-buttons in children: about two cases. Journal of Paediatrics and Childcare 32: 35-38.

- Oulmaati A, Tayache I, Hmami F (2015) The revasive hypersialorrhea ingestion of a foreign body in a newborn. Journal of Paediatrics and Childcare.

- Haennig A, Bournet B, Jean-Pierre O, Buscail L (2011) Conduct to be held in front of an ingestion of foreign objects. Hepato Gastro 18: 249-257.

- Lavarde D, Deneuville E, Dagorne M, Rambeau M, Le Gall E (2006) Rebellious asthma in relation to a little-known esophageal foreign body. Arch pediatr 13: 1047-1049.

- Michaud L, Bellaïche M, Olives JP (2009) Ingestion of foreign objects in children. Recommendation from the French-speaking paediatric hepatology, gastroology and nutrition group. Arch pediatr 16(1): 54-61.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...