Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Commentary(ISSN: 2643-6760)

The Adipocerous Sophomore - Lipoblastoma Volume 5 - Issue 2

Anubha Bajaj*

- Histopathologist, Consultant Histopathologist, New Delhi, India

Received:June 08, 2020; Published: June 24, 2020

Corresponding author: Anubha Bajaj, Histopathologist, Consultant Histopathologist, New Delhi, India

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2020.05.000209

Preface

Lipoblastoma is an exceptional, benign, lobulated, mesenchymal neoplasm arising from embryonal adipose tissue cells or lipoblasts or immature adipocytes. In concurrence with diverse adipose tissue neoplasia such as lipoma, lipomatosis, angiolipoma, myolipoma or lipoblastomatosis, lipoblastoma is categorized as a benign, mesenchymal, adipocytic neoplasm. Jaffe described lipoblastoma as an atypical lipoma with cellular constituents simulating embryonic fat or lipoblasts, in 1926. As lipoblastoma arises from embryonic adipose tissue, it is additionally nomenclated as “embryonic lipoma or foetal or embryonal lipoblastoma” [1]. Vellios denominated distinctive histological variants of lipoblastoma in 1958. A localized, superficial, singular, well circumscribed or encapsulated variant is designated as lipoblastoma whereas diffuse, multi-centric, non-encapsulated, infiltrative variant is nomenclated as lipoblastomatosis [2]. A predominantly lobulated, well circumscribed, encapsulated tumefaction simulating foetal adipose tissue, lipoblastoma is commonly situated within subcutaneous tissue. In contrast, lipoblastomatosis is a poorly defined, non-encapsulated, multi-centric, infiltrative, generally deep- seated neoplasm composed of an accumulation of foetal adipose tissue. Demography and characteristics of lipoblastomatosis is essentially similar to lipoblastoma [1,2].

Disease Characteristics

Lipoblastoma and lipoblastomatosis are commonly discerned in infants or young children beneath < 3 years of age or infrequently amidst 14 years to 24 years. Tumour emergence is variable and ranges betwixt one month to 14 years with a median age of 2 years. The condition can occasionally be congenital. Lipoblastoma configures an estimated 15% of benign mesenchymal neoplasia arising in children beneath <3 years [3]. As an estimated 90% of tumours arise below < 3 years, lipoblastoma demonstrates a male predilection with a male to female proportion of 1.5 to 3:1. Malignant metamorphoses or distant metastasis of benign lipoblastoma is unknown [3,4]. Essentially comprised of immature, persistent, embryonic adipose tissue which proliferates rapidly within the post natal period, lipoblastoma can configure an enlarged tumefaction wherein the variable tumour magnitude can extend up to 25 centimetres [3,4].

As a lobulated, mesenchymal neoplasm comprised of embryonal or foetal adipose tissue, lipoblastoma, characteristically demonstrates a benign biological behaviour, preliminary discernment, male predominance and brisk tumour evolution. Nevertheless, despite rapid progression and localized tumour infiltration of abutting anatomic structures, lipoblastoma delineates a superior prognosis [3,4]. Tumour reoccurrence is common in lipoblastomatosis and is observed in around 9% to 22% instances. Lipoblastomatosis is predominant within the head and neck region, tumours are minimally lobulated and infiltrate deep- seated skeletal muscle [3,4].

Clinical Elucidation

Lipoblastoma is commonly observed within sites of persistent immature adipose tissue. Lipoblastoma arises upon the trunk in nearly 10% to 60% subjects or extremities in roughly 40% to 45% individuals whereas tumefaction of the head and neck is exceptional. Occasionally, lipoblastoma is encountered within mediastinum, retroperitoneum, thigh, scrotum, anterior chest wall, renal pelvis, mesentery, omentum, inguinal, parotid or intra thoracic region or in abdominal locales as an intussusception, representing as an acute abdomen. Lipoblastoma confined to the retroperitoneum is discerned in below <5% instances [5,6].

Lipoblastoma arises as a gradually progressive, painless, superficial, subcutaneous, soft tissue nodule or a well circumscribed mass wherein an estimated 75% tumefaction appear upon the left side. Lipoblastoma can simulate foetal adipose tissue aggregates or a myxoid liposarcoma. Non-resected lipoblastoma generally matures into lipoma with prominent fibrous tissue septa [4]. Although accompanied by a benign biological behaviour, lipoblastoma can delineate symptoms arising due to compression of adjacent viscera. Typically, lipoblastoma is asymptomatic although

nonspecific symptoms such as indigestion, vomiting, constipation,

backache, haematuria or urinary symptoms are discerned with

pertinently localized tumefaction. Lipoblastoma situated within

the chest wall can exhibit cough, dyspnoea, airway obstruction

with impaired airway clearance and predisposition to respiratory

infections. Clinical symptoms contingent to vascular or spinal cord

compression are extremely exceptional [5,6].

Histological Elucidation

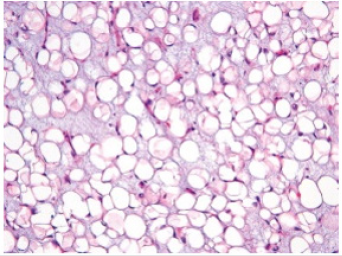

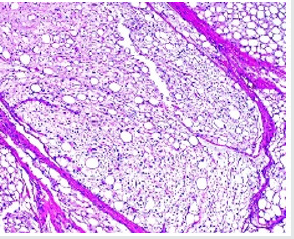

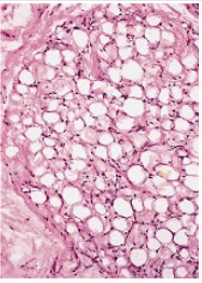

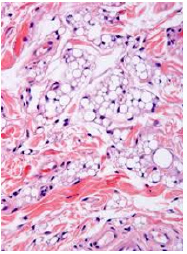

On macroscopic examination, miniature lesions of approximately 2 centimetre to 5 centimetre magnitude are discerned. Cut surface demonstrates adipose tissue aggregates with foci of gelatinous metamorphoses. Also, lipoblastoma or multi-centric lipoblastomatosis can manifest as a soft, lobulated tumefaction with a yellowish surface [6]. On fine needle aspiration cytology, a moderate to poorly cellular neoplasm is delineated. Aggregates of mature lipocytes, lipoblasts and spindle-shaped cells are intermixed with abundant, myxoid stroma and a smattering of stripped, elliptical nuclei [6,7]. Morphologically, the multinodular lipoblastoma demonstrates adipocytes in diverse stages of maturation with predominant myxoid foci and an absence of anaplasia. Microscopically, lipoblastoma with a lobulated configuration displays an admixture of mature and immature adipocytes, immature component essentially representing lipoblasts in diverse developmental stages. Contingent to age of incrimination, lipoblasts can be scarce and the neoplasm denominates lipoma- like architecture. Intervening tumour matrix can be myxoid with a plexiform, vascular pattern, akin to myxoid liposarcoma [6,7]. Distinct connective tissue septa divides the tumefaction into separate lobules. However, a lobular architecture is not preponderant in lipoblastomatosis. Occasionally, lipoblastoma or lipoblastomatosis may delineate foci of extramedullary haematopoiesis or cellular component recapitulating brown fat. Cellular maturation can occur, thus engendering a lipoma- like histological picture [6,7]. Histologically, hypo-cellular lobules of adipocytes with divergent differentiation are encountered. Pre-adipocytes, emerging as spindle-shaped or stellate cells, univacuolated or multi-vacuolated lipoblasts and mature adipocytes accumulated within centroidal lobules are discerned. Polygonal nests and cords of multi-vacuolated adipose tissue tumour cells intermingled with numerous mature adipocytes, segregated by fragments of fibro-vascular stroma are exemplified. The pseudoencapsulated, multi-lobulated, mesenchymal tumefaction is comprised of groups and clusters of peripherally disseminated immature lipoblasts demarcated with attenuated fibrous tissue septa [6,7]. Prominent fibrous tissue septa dividing tumour aggregates can be cellular. Tumour cell aggregates can be encompassed with an extracellular accumulation of mucinous matrix. Also, plexiform vascular configurations and abundant myxoid stroma circumscribes cellular lobules [7] (Figures 1-9).

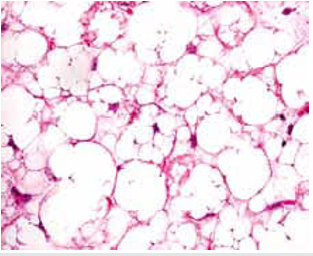

Figure 1: Lipoblastoma depicting immature and mature adipocytes, lipoblasts, fibrous tissue fragments and red cell extravasation.

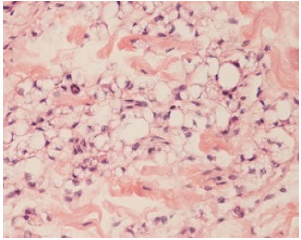

Figure 2:Lipoblastoma displaying nests of lipoblasts and immature adipocytes imbued with embryonal adipose tissue commingled with fibrous tissue septa and mature adipocytes.

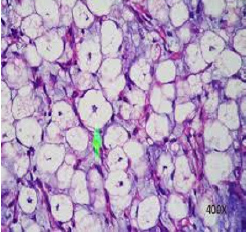

Figure 3: Lipoblastoma depicting aggregates of lipoblasts with peripheral encapsulation with fibrous tissue and intermingled mature adipocytes.

Figure 4: Lipoblastoma enunciating aggregates of vacuolated cells impacted with foetal adipose tissue and disseminated fibrous tissue septa.

Figure 5: Lipoblastoma exemplifying clusters of immature adipocytes, lipoblasts and few mature adipocytes with several fibrous tissue septa, multi-vacuolated cells and red cell extravasation.

Figure 6: Lipoblastoma exhibits accumulates of immature adipocytes, lipoblasts and mature adipocytes with centroidal, uniform nuclei, lipid-rich, vacuolated cytoplasm and fibrous tissue septa.

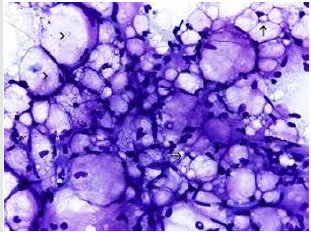

Figure 7:Lipoblastoma detected on fine needle aspiration cytology delineating lipid- rich, vacuolated cells with uniform, centric or eccentric nuclei and aggregates of fibro connective tissue.

Figure 8: Lipoblastoma depicting aggregates of immature lip oblasts, few mature adipocytes, intermixed fibrous tissue septa and red cell extravasation.

Figure 9: Lipoblastoma demonstrating aggregates of immature adipocytes with peripheral, compressed nuclei, intervening fibrous tissue septa and vascular congestion.

Immune Histochemical Elucidation

Immune histochemical evaluation with CD34, S100 protein and desmin is beneficial. Primitive mesenchymal cells are immune reactive to desmin whereas adipocytes are immune reactive to CD34 and S100 protein and vascular endothelial cells are immune reactive to CD34. Lipoblastoma is immune reactive to Ki67, CD31 and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) [3,4]. Characteristically, majority of lipoblastomas demonstrate a genomic rearrangement of 8q11-13. Genetic mutation of chromosome 811q and around q13 region (8q11-13) with rearrangements within PLAG 1 gene is discerned in an estimated 70% subjects. Assessment of aforesaid genomic rearrangements is advantageous in detecting primary or reoccurring lipoblastomas [3,4]. Also, a polysomy for chromosome 8 is discerned along with genetic translocation of t(3;8) ( p13;q21.1). On ultrastructural examination, tumour cells display an encompassing basal lamina, pinocytotic vesicles, Golgi membrane, spheroidal to elliptical mitochondria along with accumulation of intracytoplasmic glycogen and lipid. Tumour cells recapitulate a myxoid liposarcoma or cells of normal, developing adipose tissue [3,4].

Differential Diagnosis

Lipoblastoma requires a distinction from neoplasia such as lipofibromatosis or infantile fibromatosis which denominates abundant fibrous tissue. Nevertheless, a singular entrapment of mature adipose tissue cells, an absence of myxoid stroma or a plexiform vascular plexus are features substantiating aforesaid neoplasia(7,8). Lipoblastoma necessitates a segregation from adjunctive adipose tissue containing neoplasia such as lipoma, liposarcoma or teratoma. Occurrence of associated mesenchymal constituents and concomitant cystic change demarcates lipoblastoma from lipoma [7]. Teratoma often depicts discrete foci of calcification or ossification. Myxoid liposarcoma is infrequently delineated in children and lacks a distinct lobular pattern. The cellular neoplasm demonstrates giant cells with pleomorphic nuclei and diverse molecular anomalies [7,8]. Well differentiated liposarcoma is exceptionally discerned in children, is minimally cellular, displays mature adipose tissue aggregates, an absence of lipoblasts, spindle-shaped cells with enlarged, intensely stained nuclei and significant nuclear enlargement or pleomorphism. Immune reactivity to mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) and cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) is discerned. Liposarcoma is infrequent prior to ten years of age. Besides, diagnostic imaging features are invalidated [7,8].

Investigative Assay

A competently extracted surgical tissue specimen is mandated

in adult subjects in order to diagnose lipoblastoma on account

of nonspecific clinical features. Commonly, a lipoblastoma is

appropriately discerned on an accurate histological examination.

Conventional radiograph of lipoblastoma is nonspecific and demonstrates a density mass comprised of soft tissue, pertinent

to tumour magnitude, thickness and localization. Tumefaction is

devoid of calcium deposition or erosion of abutting bone on account

of rapid tumour progression [8,9]. Ultrasonography, computerized

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are

beneficial for assessing the extent, magnitude and location of

neoplasm. Computerized tomographic angiography (CTA) can

precisely evaluate critical vascular parameters.

Computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) are excellent diagnostic modalities for determining

the genesis, anatomical expanse and composition of a lipoblastoma.

Imaging features are contingent to the composition, percentage

of adipose tissue intermixed with myxoid stroma along with

concordant, intrinsic fibrous tissue, vascular configurations

and adjacent soft tissue nodules. Infants and young children

exemplify an extensive myxoid component within a lipoblastoma

whereas older children preponderantly display adipose tissue

[8,9]. Computerized tomography (CT) permits a direct evaluation

of adipose tissue component besides thick, fibrous tissue

septa traversing the tumour, tumour nodularity and tumour

enhancement on account of fibrous tissue. Magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) is a preferred diagnostic modality to evaluate the

neoplasm and segregate lipoblastoma from accumulates of normal

subcutaneous adipose tissue. Lipoblastoma is a lobulated neoplasm

demonstrating enhancement of signal intensities [8,9].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) defines intrinsic

configuration of a lipoblastoma. Adipose tissue component

delineates dense foci of signal intensities identical to subcutaneous

adipose tissue within comprehensive image sequences. Myxoid,

cystic articulations depict minimal signal intensity with T1

weighted imaging sequences and enhanced signal intensity with

T2 weighted imaging sequences, thereby indicating an augmented

water content of the neoplasm. Fibrous tissue septa exhibit

intrinsic, mildly enhanced subdivisions. Occasionally, miniature,

enhancing soft tissue nodules are enunciated. Lipoblastoma can be

subjected to a fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to confirm

the diagnosis [8,9].

Therapeutic Options

A comprehensive surgical extermination of the neoplasm with preservation of vital organs and a broad perimeter of normal, uninvolved, circumscribing soft tissue is advantageous and preferred. Additionally, dispensation of enlarged neurovascular bundles is recommended during treatment of enlarged tumours [10]. Irrespective of tumour localization, an optimal surgical eradication of the neoplasm is mandated. Comprehensive tumour resection is accompanied by an excellent prognosis as it appropriately circumvents a localized tumour reoccurrence. Distant metastasis and malignant metamorphoses of lipoblastoma is unknown [10]. Lipoblastoma demonstrates a superior prognosis with absent distant metastasis whereas potential tumour reoccurrence varies from 9% to 26% on account of inadequate initial surgical procedure. Spontaneous tumour retrogression can occur. Lipoblastoma delineating an infiltrative tumour perimeter can display repetitive tumour reoccurrences necessitating repetitive surgical extermination [9,10]. Management of lipoblastomatosis necessitates a demanding therapeutic protocol on account of multi-centric neoplasia, irregular tumour margins and enhanced proportion of tumour reoccurrence. Enlarged abdominal tumefaction can be subjected to an initial laproscopic procedure in preoperatively benign tumours amenable to surgical resection. Extensive, post-operative monitoring for 3 years to 5 years is recommended and essential [9,10].

References

- Jaffe RH (1926) Recurrent lipomatous tumour of the groin. Arch Pathol 1: 381-387.

- Vellios F, Baez J (1958) “Lipoblastomatosis: a tumour of foetal fat different from hibernoma; a report of a case, with obervations on the embryogenesis of human adipose tissue.” Am J Pathol 34(6): 1149-1159.

- Parisi M, Grenda E (2019)”Chest wall lipoblastoma in a 3 year old boy.” Respir Med Case Rep 26: 200-202.

- Shi Y, Kang Yang (2019)”Lipoblastoma of the left kidney: a case report and review of literature.” Ann Transl Med 7(7): 150.

- Guana R, Garofalo S (2019) “Infantile abdominal and pelvic lipomblastomas: a case series.” European J Pediatr Surg Rep 7(1); e104-e109.

- Jandali D, Heilingoetter A (2018)”Large gland parotid gland lipoblastoma in a teenager.” Front Paediatr 6: 50.

- Schoolmeester JK, Michal M (2018) ”Lipoblastoma –like tumour of the vulva: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, fluorescent in situ hybridization and genomic copy number profiling study of seven cases.” Mod Pathol 31: 1862-1868.

- Sakamoto S, Hashizume N (2018)”A large retroperitoneal lipoblastoma: a case report and literature review.” Medicine (Baltimore) 97: e12711.

- Han JW, Kim H (2017)”Analysis of clinical features of lipoblastoma in children.” Pediatr Haematol Oncol 34(04): 212-220.

- Brundler MA, Kurek KC (2018)” Submucosal colonic lipoblastoma presenting with colo- colonic intussusception in an infant.” Pediatr Dev Pathol 21(04): 401-405.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...