Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Case Report(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Recurrent Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in a Male Child: A Case Rarity Volume 5 - Issue 3

Nitin Jain1, Parveen Kumar2* and Shandip Sinha3

- 1Department of Pediatric Surgery, RMC, Bareilly, India

- 2Department of Pediatric Surgery, Chacha Nehru Bal Chikitsalya, India

- 3Department of Pediatric Surgery, Madhukar Rainbow Children Hospital, India

Received:June 10, 2020; Published: July 07, 2020

Corresponding author: Parveen Kumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Chacha Nehru Bal Chikitsalya, New Delhi, India

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2020.05.000211

Abstract

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) is the most frequent surgical condition in children. Incomplete pyloromyotomy is an infrequent complication, but recurrent pyloric stenosis (RPS) is extremely rare. We report here a case of late-onset recurrence of IHPS in a 7-year-old male child, after successful pyloromyotomy. He presented with abdominal pain, recurrent episodes of nonbilious vomiting and upper abdominal fullness after taking meals that relieved on vomiting. These symptoms started around 4 months after successful pyloromyotomy done at 4 weeks of age. Child underwent series of radiological investigations including upper GI endoscopy that confirmed gastric outlet obstruction with thickened pylorus. Multiple management options are proposed but we preferred ‘heineke mikulicz pyloroplasty’ in our case.

Introduction

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a common cause of

gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) in neonates, with an incidence of

1.5 to 3 per 1000 live births. Onset is seen usually between 2 to 8

weeks of life, with classic presentation of feeding intolerance with

projectile, non-bilious emesis. Diagnostic work up usually reveals

a hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. Ultrasound or

fluoroscopic upper gastrointestinal series can be used to facilitate

diagnosis when the clinical picture and physical exam are equivocal.

The etiology of IHPS is not properly understood. Various authors

have suggested its congenital or acquired nature [1]. Ramstedt’s

pyloromyotomy is the current standard of care, with high curative

rate and minimal post-operative morbidity. As incomplete

pyloromyotomy is a well-documented post-operative complication,

there are very few cases of true recurrent PS.

Multiple options are proposed for the management of recurrent

PS including pneumatic dilatation or botulinum toxin injection as

well as operative management in form of pyloroplasty, Billroth I,

Billroth II procedures [2-4]. Here, we present a case of isolated

recurrent PS in 7 years old male child following successful

management with routine pyloromyotomy.

Case Report

A 7-year-old male child presented with abdominal pain, recurrent episodes of non-bilious vomiting and upper abdominal fullness after taking meals that relieved on vomiting. Parents also gave history of vomiting of partially digested food material eaten few hours earlier. These symptoms started around 4 months after the child had undergone successful pyloromyotomy at 4 weeks of age. At the time of first presentation during neonatal period, symptoms of repeated episodes of vomiting and upper abdominal fullness immediately after feeding were recognised by parents and child underwent open Ramstedt pyloromyotomy. At home, he tolerated full feeds with no vomiting and gained weight. Child was symptoms free until about 4 months postoperatively. Initially the symptoms were not severe and child had bloating, early satiety, foul-smelling regurgitations and over the following year, child experienced few episodes of infrequent non-bilious vomiting. As per his mother child was gaining weight at good pace until when the frequency of vomitings gradually increased over 4-5 years. Child later developed abdominal pain and recurrent non bilious vomitings after about 20 to 30 minutes of a feed.

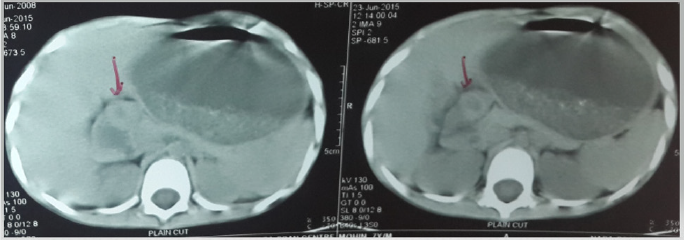

During follow-up child was being treated for gastro-esophageal reflux with persistent symptoms. Later, child presented to our emergency. On examination, he had signs of dehydration, with pulse rate of 119/minute, low volume and B.P was 92/48 mmHg. Blood investigations revealed Hb 9.3g/dl, TLC 7250/dl, Platelet count 3.59L/mm3, HCT 41%, protein 4.8g/dl, serum albumin 2.3g/dl, blood urea 21 mg/dl, serum creatinine 0.9mg/dl, Na+ 129meq/L, K+ 3.1meq/L & Cl- 95meq/L. Venous blood gas (VBG) analysis showed pH 7.47, pCo2 34, pO2 59, Hco3 29. Weight of the child at presentation was less than 3rd Centile on growth chart. Child was managed with fluid resuscitation, and blood investigation revealed correction of dehydration as manifested by normalisation of hematocrit to 36% and VBG pH 7.36, pCo2 31, pO2 66, Hco3 24. Child underwent series of radiological investigations that included USG abdomen, which showed dilated stomach and contrast enhanced CT scan with oral contrast confirmed grossly dilated stomach extending inferiorly to the level of iliac fossa and displaced the bowel loops posteriorly. On successive sections there was circumferential thickening of distal stomach. All these features pointed towards GOO because of PS (Figure 1).

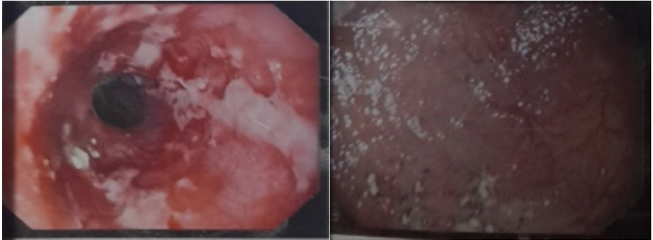

Upper GI endoscopy showed multiple ulcerations with friability at the lower end of esophagus. Stomach was dilated with food residue and normal fundus, body and antral regions but pyloric opening couldn’t be negotiated. After workup child was planned for surgery. Intra-operative findings were dilated stomach and thickened pylorus. We performed ‘heineke mikulicz pyloroplasty’ involving transversely closed longitudinal incision across the pylorus. The nasogastric tube was removed on 3rd post-operative day (POD) and child was allowed liquids on 4th POD with soft diet on 5th POD (Figure 2).

Outcome and follow-up

He was discharged on POD-7 on soft diet and tab Lanzol 15mg DT for 2 weeks. At his 2-week post-operative visit, he was asymptomatic and tolerated feedings without bloating or emesis. The histopathological examination was consistent with HPS. He remained completely asymptomatic at 1-year follow-up.

Discussion

Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy (PM) remains the gold standard treatment for IHPS [5]. Emesis is a frequent postoperative complaint after pyloromyotomy and it occurs in 36–90%of cases [4]. Usually vomiting stops spontaneously after few days. Incomplete pyloromyotomy is suspected when vomiting persists and lasts of more than 5 days. There is a criterion to differentiate recurrent PS from incomplete pyloromyotomy which includes [6];

a. The patient must have resolution of symptoms for duration of

at least three weeks postoperatively.

b. The patient must demonstrate weight gain.

c. Evidence of restenosis must be confirmed with imaging or on

exploration (all these conditions are consistent with our case).

Huang et al. [7] showed that the immediate postoperative

resolution of emesis after a successful pyloromyotomy is from

an increase in the diameter of the intramuscular pyloric canal

rather than an immediate regression in the thickness or length of

the pyloric muscle. In incomplete pyloromyotomy pyloric canal

diameter will not be seen to increase in diameter on USG who

presented with repeated vomiting in immediate post-operative

period. True recurrence of HPS is quite rare with only a few case

reports in literature.

The etiology of recurrent PS, as IHPS itself, is unclear. It appears

that pathological evolution of HPS as well as recurrent PS as a true

surgical entity is similar and separate from incomplete PM. It has

been suggested that the process which drives hypertrophy of the

pylorus is in still in evolution when initial pyloromyotomy was

performed which after initial symptom free interval progressed

to true recurrent PS [3,8]. In any case of recurrent PS, initial

management is conservative with bowel rest and nasogastric

decompression with trial periods ranging from 7 to 21 days. The

medical management using atropine, botulinum toxin injection and

surgical management including pyloroplasty, Billroth I, Billroth II

procedures, and pneumatic balloon dilatation has been proposed

[2-4]. We did ‘heineke mikulicz pyloroplasty’ in our case because of

its ease and simplicity with preservation of normal anatomical tract

and less complications.

A close differential diagnosis of Jodhpur disease (JD) needs

mention. It presents as primary acquired gastric outlet obstruction

in infancy and childhood, with very similar presentation to our

case. Jodhpur disease has predilection for male sex [9]. There

are certain differentiating features between these two entities

[10]. A) Ultrasonography shows normal pyloric canal with no

pyloric muscle hypertrophy in Jodhpur disease (JD) but shows

narrow pyloric canal with pyloric muscle hypertrophy in HPS. B)

UGIE in JD shows no intra-luminal pathology with normal gastric

mucosal rugosities in a large-sized stomach while in HPS Antral

folds hypertrophy with dilated stomach. C) On histopathological

examination (HPE), Jodhpur disease shows normal cellular pattern of all coats without inflammatory and fibro-proliferative nature

[9]. HPE was consistent with HPS in our case. It showed marked

congestion of pyloric mucosa. Muscularis mucosa and muscularis

propria showed hypertrophy and hyperplasia of muscle bundles

along with haphazardly directed muscle bundles with interspersed

fibro-collagenous tissue.

Conclusion

True Recurrent PS is a rare condition with unclear etiology. There may be an increasing incidence due to early diagnosis with modern investigations. Utilizing the evidences & criteria available for diagnosis, we believe pyloroplasty seems to be the most effective and safest intervention for recurrent PS.

Conflicting Interest

Nil

Acknowledgement

Patient was managed at Maulana Azad Medical college, Lok Nayak Hospital.

References

- Al-Ansari A, Altokhais TI (2016) Recurrent pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Int Off J Jpn Pediatr Soc 58(7): 619-621.

- Feng J, Gu W, Li M, Yuan J, Weng Y, et al. (2005) Rare causes of gastric outlet obstruction in children. Pediatr Surg Int 21: 635-640.

- Ankermann T, Engler S, Partsch CJ (2002) Repyloromyotomy for recurrent infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after successful first pyloromyotomy. J Pediatr Surg 37(11): E40.

- Boybeyi Ö, Karnak İ, Ekinci S, Ciftci AO, Akçören Z, et al. (2010) Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: definition of diagnostic criteria and algorithm for the management. J Pediatr Surg 45: 1777-1783.

- Keys C, Johnson C, Teague W, Mackinlay G (2015) One hundred years of pyloric stenosis in the Royal Hospital for Sick Children Edinburgh. J Pediatr Surg 50: 280-284.

- Cappiello CD, Strauch E (2014) A rare case of recurrent hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2: 519-521.

- Huang Y, Lee H, Yeung C, Chen W, Jiang C, et al. (2009) Sonogram before and after pyloromyotomy: the pyloric ratio in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Neonatol 50: 117-120.

- Kuckelmana J, Marencoa C, Doa W, Barlowb M (2019) Recurrent pyloric stenosis and definitive operative management with repeat pyloromyotomy. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 42: 24-27.

- Sharma KK, Ranka P, Goyal P, Dabi DR (2008) Gastric outlet obstruction in children: an overview with report of “Jodhpur disease” and Sharma’s classification. J Pediatr Surg 43: 1891-1897.

- Kajal P, Bhutani N, Kadian YS (2019) Primary acquired gastric outlet obstruction (Jodhpur disease). J Pediatr Surg 40: 6-9.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...