Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Case Report(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Primary Gastric Conduit Cancer 10 Years after Esophagectomy for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Volume 1 - Issue 4

Johanna Lou1 and Jeffrey M Farma2*

- 1Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia

- 2 Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia

Received: August 13, 2018; Published: August 16, 2018

Corresponding author: Jeffrey M Farma, Department of Surgical Oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA 19111

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2018.01.000116

Abstract

Primary gastric conduit cancer (GCC) is a known but rare occurrence post-esophagectomy with gastric reconstruction of the esophagus. As improvements in post-esophagectomy treatment and surveillance have increased patient survival, GCC is becoming more common, with a reported incidence of 0.2-3.5%. We present the case of a 76-year-old man with metachronous adenocarcinoma of the gastric conduit antrum 10 years after Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. He was treated by a total gastrectomy with colonic interposition for esophageal reconstruction.

Keywords:Gastric neoplasms; Gastric cancer; Stomach cancer; Gastrectomy; Esophageal cancer; Esophagectomy

Abbreviations: GCC: Primary Gastric Conduit Cancer; EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EUS: Endoscopic Ultrasound; SCC: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Introduction

Surgical management of esophageal cancer involves esophagectomy with esophageal reconstruction. Creation of a gastric conduit is the preferred approach for reconstruction due to the stomach’s rich blood supply, length, and ease of transposition [1-3]. Esophageal cancer is associated with a risk of second primary malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract with an incidence of 8-12% [1,3-5]. Gastric conduit cancer (GCC) is defined as a metachronous cancer in the gastric conduit used for esophageal reconstruction after esophagectomy [3,4]. As improvements in post-esophagectomy treatment and surveillance have increased patient survival, GCC is becoming more common, with a reported incidence of 0.2-3.5% [1,4-7]. This is the case of a 76-year-old man with metachronous adenocarcinoma of the gastric antrum 10 years after Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. He was treated by a total gastrectomy with colonic interposition for esophageal reconstruction.

Case Report

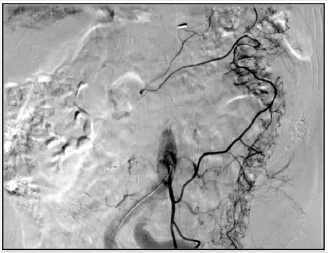

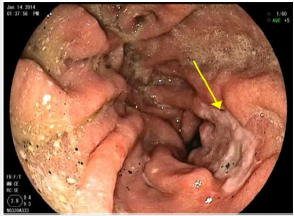

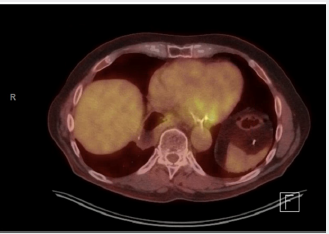

A 76-year-old man presented to the Thoracic Surgery clinic with a 1-month history of dyspepsia and left upper abdominal spasms. He reported no other symptoms. He is a former smoker with a 30-pack-year history. Ten years prior, he was diagnosed with clinical Stage IIIA T3N1M0 esophageal adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. He underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation with fluorouracil and cisplatin, followed by an open Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy. The final staging after induction therapy and surgical resection was ypT0N0. Work up of his presenting symptoms included a barium swallow that showed mild narrowing at the anastomosis and irregularity at the stomach antrum. A subsequent Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed a 1.5cm superficial ulcer along the lesser curvature of the stomach and posterior wall of the gastric body (Figure 1). Biopsy of this lesion proved poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells and a negative H. pylori test. Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS), CT scan, and PET scan were performed for staging. EUS showed a 3-cm ulcer involving the muscularis propria with no lymphadenopathy. The CT showed a right upper lobe infiltrate that resulted in a positive acid-fast stain and MAC culture. The PET scan showed mild activity in the gastric conduit inferior and medially above the diaphragm. The final clinical staging was T2NxM0 (Figure 2). We discussed this patient’s case at our multidisciplinary gastrointestinal tumor board. Given his prior oncologic history and radiation therapy, he underwent induction chemotherapy using epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil. He received two cycles before developing mucositis. Repeat PET scan showed interval improvement, and the decision was made forego a third cycle and proceed with surgery. The patient had a preoperative angiogram to evaluate the blood supply to the colon (Figure 3).

Figure 1: EGD of the gastric conduit at the ulcer site revealing thickened wall measuring 4mm and involving the muscularis propria.

Figure 2: PET scan showing mild activity in the gastric conduit inferior and medially above the diaphragm.

The patient underwent an open resection in a combined case with thoracic and GI surgeons. After induction of general anesthesia, the thoracic surgeon mobilized the intrathoracic stomach and performed lymphadenectomy of level 7 and 8 nodal stations. The GI surgeon obtained access into the abdominal cavity and confirmed that there was no evidence of liver or peritoneal metastases. Once adhesions were lysed, the gastric conduit was mobilized. Gastroepiploic vessels were ligated, and the duodenum was transected just distal to the pylorus. A D2 lymphadenectomy was performed. After obtaining adequate control of the middle colic vessel branches, the colon was transected just proximal to the right branch of the middle colic and just distal to the marginal artery on the descending colon. The colonic segment was mobilized to the chest without tension and a colocolonic anastomosis was formed between the mid transverse to the sigmoid colon. A Rouxen- Y Colo jejunostomy was subsequently performed. The colonic interposition graft was advanced through the esophageal hiatus, and the thoracic surgeon successfully performed esophagocolonic anastomosis. Surgical pathology showed no involvement of 0 out of 25 lymph nodes. The stomach had residual microscopic foci of signet ring cell carcinoma invading into submucosa (T1b) with no lymphovascular invasion for a final diagnosis of stage IB disease. All surgical margins were negative. The patient received adjuvant FOLFOX6 for 4 cycles, with oxaliplatin held for the last cycle. At his 4-year follow-up visit, he remains disease free.

Discussion

Primary gastric conduit cancer is a known but still rare occurrence post-esophagectomy. While potential causes of GCC are debated, three main theories are consistently mentioned in the literature. H. pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma [8]. However, there is equivocal evidence that H. pylori infection is contributory to GCC. A retrospective study by Bamba et al of 25 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma found only one patient with H. pylori detected in the resected gastric tube [1]. In a case report series by Ho et al, only one patient tested positive for H. pylori on the antrectomy specimen of the gastric tube despite a negative test on their pre-operative endoscopic biopsy [3]. The low incidence of H. pylori is attributed to chronic biliary reflux after pyloroplasty and is consistent with previous studies that looked at H. pylori infection in relation to GCC [4,6,9,10]. Our patient had a negative H. pylori test on his pre-op biopsy, and one was not performed on his post-op specimen. Chronic biliary reflux may itself increase the risk of GCC. Gastric reflux has a well-known association with esophageal metaplasia [11]. It is possible that bile reflux due to pyloroplasty increases the risk of intestinal metaplasia and resulting carcinogenesis [1,9,10]. Across several retrospective studies, GCC presented significantly more in the mid and lower third of the reconstructed esophagus [1,12]. In our patient who presented with dyspepsia and a lesion at the level of the diaphragm, it is reasonable to consider the contribution of reflux to the development of a metachronous lesion. Another potential cause of GCC may be related to local GI tract exposure to radiation and toxins. Our patient received radiation initially for his primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ho et al noted submucosal tissue fibrosis in patients with prior chemoradiation, leading to difficulty in endoscopic submucosal dissection of metachronous gastric cancer [3].

While this suggests some sort of post-radiation cellular transformation, there is no concrete evidence of radiation in the role of GCC development [5]. Generally secondary radiation induced cancers occur approximately 10 years after treatment. Further studies need to be done to evaluate the long-term risk involved with metachronous cancers. Similarly, Strong et al proposed the concept of “field cancerization” several decades ago. This theory suggests that exposure of the digestive tract to toxins, most notably tobacco or alcohol, may promote metaplasia and carcinogenesis [13,14]. There is evidence that tobacco, but not alcohol, increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, particularly in patients with Barrett’s esophagus [15]. Although our patient does not have a history of Barrett’s esophagus, he has a 30-pack-year history. One interesting aspect of this patient’s history is his initial diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Across 126 patients in several retrospective studies and case reports, only 2 patients were noted to have GCC after esophagectomy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nearly all the remaining patients were initially diagnosed with esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) [1,3,5,12,14,16-19]. This large discrepancy in the presenting esophageal pathology can be attributed to the epidemiology of esophageal cancer. In high risk geographical regions spanning from Northern Iran through central Asian to North-Central China, 90% of esophageal cancer cases are SCC [20,21]. In Western countries, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been rising, while the incidence of SCC has been declining [22,23]. With the bulk of literature coming from Japan and other countries with a higher incidence of esophageal SCC, it is not surprising that there are fewer published reports of GCC in patients with a history of esophageal adenocarcinoma [1,3-7,9-12,17-19,21-23]. Future studies are needed to explore potential differences in GCC between these two esophageal cancer pathologies.

Treatment of GCC is should be based on depth of tumor invasion and includes surgery, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), and palliative chemoradiation [4,5]. Total gastric conduit resection is technically challenging, with a mortality reported up to 50% [5]. Complete surgical resection, as performed in our patient, consists of an esophagectomy with complete lymph node dissection and reconstruction of the GI tract with the colon or small bowel [5,19]. An alternative surgical option includes partial gastric resection for palliation [5,12]. More recently, ESD has become increasingly favored [17]. A retrospective study by Lee et al reported higher 3-year survival with ESD compared to gastrectomy and conservative chemotherapy (100 vs. 50 vs. 9.1). However, they do not report whether any patients who underwent ESD received induction therapy prior to their initial esophagectomy. A case reported by Ho et al described an unsuccessful ESD due to extensive tissue fibrosis in a patient with prior chemoradiation [3]. Our patient’s history of induction chemoradiation was considered, and it is unlikely that ESD would have been successful. Despite the high rate of mortality associated with total gastrectomy, our patient is disease free 4 years after his surgery in a joint case by a thoracic and complex general surgical oncologist. This case reiterates the importance of longterm surveillance after esophagectomy with gastric reconstruction. The median time between initial esophagectomy and detection of a second primary gastric cancer ranged from 57-86 months [1,12,17]. Our patient was symptomatic and presented with a gastric conduit cancer 10 years after his Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy. While this exceeds the reported median times of presentation, his late presentation does not fall outside the realm of possibility given a 10-year incidence rate of 5.7-8.1% [1,17]. Most importantly, our patient’s case makes an argument for prolonged surveillance for up to 10 years after esophagectomy [1,5,19,24].

Conclusion

Cancer of the gastric conduit after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer has been increasing in incidence as treatment and surveillance improves. Our case of a 76-year-old man with adenocarcinoma of the gastric conduit 10 years after Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy for esophageal adenocarcinoma provides learning value and suggests there may be benefit to long-term surveillance of these patients.

References

- Bamba T, Kosugi S, Takeuchi M, Kobayashi M, Kanda T, et al. (2010) Surveillance and treatment for second primary cancer in the gastric tube after radical esophagectomy. Surg Endosc 24(6): 1310-1317.

- (2018) National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers.

- Ho C, Tong DKH, Tsang JS, Law SYK (2014) Post-esophagectomy gastric conduit cancers: Treatment experiences and literature review. Dis Esophagus 27(2): 141-145.

- Okamoto N, Ozawa S, Kitagawa Y, Shimizu Y, Kitajima M (2004) Metachronous gastric carcinoma from a gastric tube after radical surgery for esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 77(4): 1189-1192.

- Sugiura T, Kato H, Tachimori Y, Igaki H, Yamaguchi H, et al. (2002) Second primary carcinoma in the gastric tube constructed as an esophageal substitute after esophagectomy. J Am Coll Surg 194(5): 578-583.

- Kise Y, Kijima H, Shimada H, Tanaka H, Kenmochi T, et al. (2003) Gastric tube cancer after esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell cancer and its relevance to Helicobacter pylori. Hepatogastroenterology 50(50): 408-411.

- Matsubara T, Yamada K, Nakagawa A (2003) Risk of second primary malignancy after esophagectomy for squamousc carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. J Clin Oncol 21(23): 4336-4441.

- Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ (1999) Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 94(9): 2373-2379.

- Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P (1996) Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 20(10): 1161-1181.

- Nonaka S, Oda I, Sato C, Abe S, Suzuki H, et al. (2014) Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer after esophagectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 79(2): 260-270.

- Sobala GM, O Connor HJ, Dewar EP, King RF, Axon AT, et al. (1993) Bile reflux and intestinal metaplasia in gastric mucosa. J Clin Pathol 46(3): 235-240.

- Shirakawa Y, Noma K, Maeda N, Ninomiya T, Tanabe S, et al. (2018) Clinical characteristics and management of gastric tube cancer after esophagectomy. Esophagus 15(3): 180-189.

- Strong MS, Incze J, Vaughan CW (1984) Field cancerization in the aerodigestive tract its etiology, manifestation, and significance. J Otolaryngol 13(1): 1-6.

- Jablonski S, Piskorz L, Wawrzycki M (2012) Gastric tube resection due to metachronic cancer and a recurrence in anastomosis after Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy case report. World J Surg Oncol 10: 83.

- Cook MB, Kamangar F, Whiteman DC, Freedman ND, Gammon MD, et al. (2010) Cigarette smoking and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 102(17): 1344-1353.

- Dranka Bojarowska D, Lewinski A, Grabarczyk A, Lampe P (2015) Primary Adenocarcinoma in an Oesophageal Gastric Graft - Case Report. Pol Przegl Chir 87(2): 97-101.

- Lee GD, Kim YH, Choi SH, Kim HR, Kim DK, et al. (2014) Gastric conduit cancer after oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer: incidence and clinical implications. Eur J Cardiothroac Surg 45(5): 899-903.

- Mukasa M, Takedatsu H, Matsuo K, Sumie H, Yoshida H, et al. (2015) Clinical characteristics and management of gastric tube cancer with endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 21(3): 919- 925.

- Oki E, Morita M, Toh Y, Kimura Y, Ohgaki K, et al. (2011) Gastric cancer in the reconstructed gastric tube after radical esophagectomy: a singlecenter experience. Surg Today 41(7): 966-969.

- Gholipour C, Shalchi RA, Abbasi M (2008) A histopathological study of esophageal cancer on the western side of the Caspian littoral from 1994 to 2003. Dis Esophagus 21(4): 322-327.

- Tran GD, Sun XD, Abnet CC, Fan JH, Dawsey SM, et al. (2005) Prospective study of risk factors for esophageal and gastric cancers in the Linxian general population trial cohort in China. Int J Cancer 113(3): 456-463.

- Pohl H, Sirovich B, Welch HG (2010) Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence: Are we reaching the peak? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19(6): 1468-1470.

- Lu CL, Lang HC, Luo JC, Liu CC, Lin HC, et al. (2010) Increasing trend of the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, but not adenocarcinoma, in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control 21(2): 269-274.

- Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, et al. (2006) Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer 9(2): 93-98.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...