Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Review Article(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Malignant Pleural Effusion as the Sole Presentation of High Grade Serous Carcinoma of Fallopian Tube-A Case Report and Literature Review Volume 6 - Issue 5

Jessica Jay Fang1#, I Ning Chen1#, Chia-Chin Tsai3, Jiantai Timothy Qiu1,2,4, I Te Wang1* and Yen-Hsieh Chiu1*

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan

- 3Department of Pathology, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan

- 4International PhD Program of Cell Therapy and Regenerative Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan

- #Both first authors contributed equally to this manuscript

- *Both corresponding authors contributed equally to this manuscript

Received:May 21, 2022; Published:June 10, 2022

Corresponding author: Yen Hsieh Chiu, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2022.06.000248

Abstract

Objective: Primary Fallopian Tube Carcinomas (PFTCs) are gynecologic malignancies which mostly present abdominal symptoms or vaginal discharge. However, Malignant Pleural Effusion (MPE) as the initial and sole presentation of PFTC without abdominal symptoms and signs is very rare.

Case report: We report a 68-year old female presented with MPE but her transvaginal ultrasound and Computed Tomography (CT) of abdominal and pelvic organs were negative for any suspicious tumor lesion. By combined immunohistochemistry of pleuracentesis, serum CA-125, and PET-CT narrows the diagnosis to a gynecologic origin. A final diagnosis of primary fallopian tube carcinoma originated from small foci of Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma (STIC) was made by a laparoscopic surgery. By the literature review data, this is the second reported clinically occult primary fallopian tube carcinoma presenting only with malignant pleural effusion.

Conclusion: PFTCs initially presenting as MPE are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. By combined immunohistochemistry of thoracentesis, tumor marker, and image study narrows the diagnosis to a gynecologic origin. Timeline of precancerous lesion (p53signature, STIC) to high-grade serous carcinoma and transmission routes of MPE were also discussed and presented in this report.

Introduction

Primary Fallopian Tube Carcinomas (PFTC) are rare tumors that account for only 0.3%~1% of all gynecologic malignancies [1]. The most common symptoms and signs of PFTC mimic those of Epithelial Ovarian Carcinomas (EOC), including abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding and/or watery discharge [2]. It is possible that the true incidence of PFTC has been underestimated, because PFTCs may have been mistakenly identified as ovarian tumors during initial approach. The pathognomonic clinical presentations of PFTC known as the Latzko triad of symptoms, including intermittent, profuse, serosanguinous vaginal discharge, colicky pain, often relieved by the discharge, and abdominal or pelvic masses, has been reported in less than 15% of patients with PFTC [1-5]. However, Malignant Pleural Effusion (MPE) as the sole presenting feature of clinically occult PFTC was rarely reported. For our best knowledge, only one case was reported in 2017 by Hiensch, et al. [3]. Here, we present the second case of PFTC manifesting itself as MPE without clinically apparent adnexal or peritoneal disease.

The accurate rate of preoperative diagnosis of PFTC is low and even the intra-operative diagnosis is missed in up to 50% of patients [3]. It is also difficult to diagnose PFTC radiologically using either ultrasound, Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) due to limited tumor size at primary site and even spreading lesions. PFTC may metastasize by different possible mechanisms. Tumor can be spread by the trans-coelomic exfoliation of cells that implant throughout the peritoneal cavity. Tumor spread can also occur by means of contiguous invasion, transluminal migration and lympho-hematogenous dissemination. In approximately 80% of PFTC patients with advanced disease, metastases are confined to the peritoneal cavity [4]. However, PFTC also has the propensity to bypass the peritoneum enroute to distal location. Therefore, PFTC is uniquely suited to initially manifest as a Cancer of Unknown Primary (CUP) due to its small size at the time of spread and to its potential for distant metastasis [3].

Case Presentation

A 68-year old female with medical history of dyslipidemia presented with palpitation, chest tightness, and shortness of breath for 5 days. She denied cough, fever, chest pain, hemoptysis, abdominal pain or loss of body weight. She had a past history of right oophorectomy due to endometrioma 30 years ago and received laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to cholecystitis 20 years ago. She was nulliparous with one artificial abortion due to Down’s syndrome 30 years ago. She is currently postmenopausal. She had a family history of colon cancer (her father and grandfather).

Figure 1: Chest radiograph showed atelectasis of right lower lung with moderate right pleural effusion.

Her vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal at admission. Physical examination revealed reduced breathing sounds over right lung base with crackles and dullness to percussion. There were no cardiac bruits or gallops on auscultation, nor any palpable lymphadenopathy or edema. Abdominal examination showed no specific findings. Her electrocardiogram was unremarkable, and cardiac echogram revealed an ejection fraction of 56%. Laboratory examinations including complete blood count, serum chemistry, liver function tests, and cardiac enzymes were all within normal limits. Tumor markers were all within normal limit except an elevated CA-125 (198.1 U/mL, normal range: less than 35 U/ mL). Chest radiograph showed atelectasis of right lower lung with moderate right pleural effusion (Figure 1,1A). An ultrasound-guided right thoracentesis was performed and yielded serosanguinous pleural fluid of 1380mL. Analysis of pleural effusion showed exudative character with presence of many malignant cells, some mesothelial cells, and lymphocytes. Immunohistochemical studies for malignant cells in pleural fluid showed diffusely positive for PAX8, focally positive for CK7 and calretinin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, CDX2, and TTF-1, suggesting a metastatic tumor originated from Müllerian system, urinary system or thyroid gland.

Figure 1A: Computed Tomography showed mild pleural effusion with atelectasis in bilateral lower lung base and patchy infiltrates in the right middle lobe.

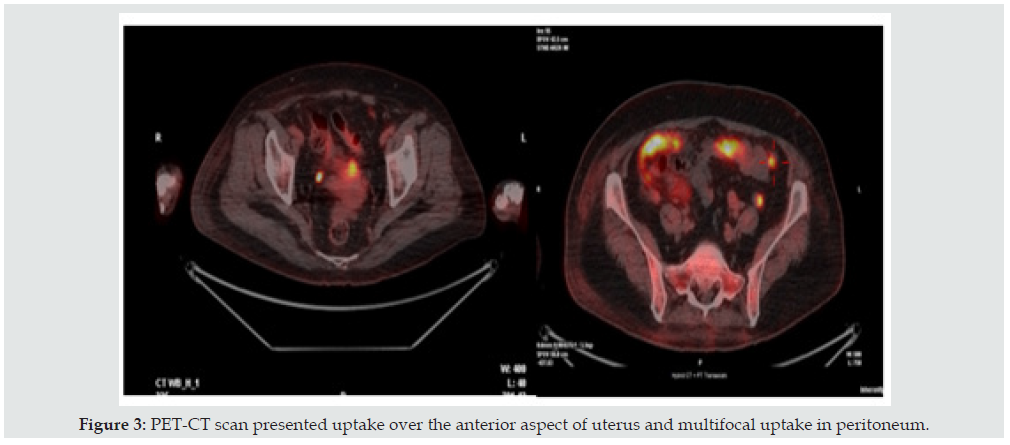

Due to an elevated CA-125, a malignancy of ovarian origin was considered. The patient received transvaginal ultrasound but showed no specific finding (Figure 2). In searching for possible primary tumor responsible for her malignant pleural effusion, the patient underwent further imaging studies. A Computed Tomography from chest to abdomen showed mild pleural effusion with atelectasis in bilateral lower lung base and patchy infiltrates in the right middle lobe (Figures 1 & 2). There were no specific findings within the abdomen except some liver cysts. Thallium scan of heart was performed but showed negative finding. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were also performed but showed negative for tumor lesion. However, her Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) scan revealed suspicious multifocal peritoneal tumors with a 2.3cm tumor in the anterior aspect of the uterus (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Transvaginal ultrasound showed normal-sized uterus and bilateral ovaries with an hyperechoic shadow of the endometrium.

Figure 3: PET-CT scan presented uptake over the anterior aspect of uterus and multifocal uptake in peritoneum.

Under the tentative diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy, diagnostic laparoscopy was arranged. At surgery, the patient was found to have papillary tumor mass, about 2cm in diameter, at serosa of lower segment of uterus and vesico-cervical reflection of uterus. The adnexa were grossly normal but miliary tumor lesions were noted over peritoneum near bilateral tubal fimbrial ends. The cul-de-sac was not adhesive but with multiple tumor seeding. Furthermore, multiple variable-sized nodules with hard consistency were noted over the omentum (Figure 4). The omental lesion was positive for adenocarcinoma by intraoperative frozen section examination. There were also miliary tumor implants over the subdiaphragmatic surface of the liver. Minimal ascites was noted. The patient underwent optimal debulking surgery including hysterectomy, right salpingectomy (status post right oophorectomy 30 years ago), left salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and omentectomy.

Figure 4: Papillary tumor mass at serosa of lower segment of uterus and vesico-cervical reflection. B&C: Omentum cake with multiple variable-sized nodules.D: Miliary tumor lesions were noted over peritoneum. R’t side fallopian tube was in normal sized. Peritoneal cancer was more favored than the final diagnosis of PFTC.

By gross pathologic examination of the specimen, the resected uterus was atrophic with rough serosa focally without obvious tumor lesion. The accompanied bilateral fallopian tubes were normal in shape with rough serosa. Left ovary was identified, and it was in normal appearance (Figure 5). Fragmented omental tissues with frankly tumor nodules, measuring up to 5.5 x 3.5 x 1.8 cm in size, were noted. By microscopic examination, a high-grade serous carcinoma, measuring 0.6 x 0.4 x 0.3 cm in size, was found at fimbrial end of left fallopian tube. Nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitoses could be easily found (Figure 6). Foci of Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma (STIC) were also noted. Tumor implants were present at serosa of uterine corpus and right fallopian tube. Omentum was also positive for adenocarcinoma (Figure 7). No metastatic carcinoma in pelvic lymph nodes was found. Immunohistochemical study of tumor cells for p53 and p16 showed positive reaction. A high-grade serous carcinoma of fallopian tube with tumor involved uterine low segment and widespread seeding on omentum was diagnosed. She was pathologically staged as T3cN0M1a with AJCC TMN stage IVA. Immunohistochemistry testing for mismatch repair proteins including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 showed intact nuclear expression of mismatch repair proteins. Molecular testing for BRAF and KARS genes showed wild type without mutation. Genetic assay results showed both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with Paclitaxel and Carboplatin intravenously. There were no significant adverse effects after chemotherapy, and she was discharged uneventfully. Subsequent chemotherapy was accomplished, and she was followed at our out-patient department. Maintenance therapy by PARP-inhibitor (Olaparib) was also prescribed due to her BRCA mutation. She has remained no evidence of disease recurrence according to her physical examination, image studies, and tumor marker levels (CA- 125) on follow up.

Figure 5: Gross pathologic examination of the specimen, the resected uterus was atrophic with rough serosa focally without obvious tumor lesion. Bilateral fallopian tubes were normal in shape with rough serosa. Left ovary was identified, and it was in normal appearance (Right oophorectomy 30 years ago) (Figure 3).

Figure 6: Primary tumor at left fallopian tube; atypical mitosis could be found (arrow). (Hematoxylin and Eosin, 400X).

Discussion

Malignant Pleural Effusions (MPE) are most frequently (50-65%) caused by metastatic lung and breast cancers. They are commonly unilateral and are reflective of poorer prognosis. Pathogenesis of MPE is thought to be caused by the hyperpermeability of microvascular tissue as a result of trans-diaphragmatic migration of malignant peritoneal fluid, deposition of neoplastic cells into the pleural cavity or invasion of cancer cells into lymphatic vessels [3,6,7]. Current guidelines recommend thoracentesis for diagnosis. However, the sensitivity of cytological diagnosis for MPE using thoracentesis is relatively poor with an accuracy of only 62%. The primary lesion of MPE is often difficult to identify histologically, even in cytologically positive samples [7]. Despite extensive work up, up to 11% of MPE are still from CUP, and potentially 5% may originate in the female reproductive system among CUP [6,8]. In gynecological malignancies, Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma (EOC) is the most common neoplasm associated with MPE, which usually occur in the context of obvious peritoneal involvement in this malignancy [3]. Recent advances in management of MPE and CUP highlights the use of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies and biomarkers of MPE, which has proven useful in helping to evaluate the primary tumor histology in patients with CUP [6,9].

Previous studies suggest that hybrid PET-CT should be utilized in the workup of CUP which aids the detection of primary tumor sites with a diagnostic accuracy of 78%, sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 74%, positive predictive value of 88.7% and negative predictive value of 59% [6,10]. In our case, PET-CT played an important role in detecting the primary tumor site. In contrary to the first case reported by Hiensch, et al. which showed only paraaortic lymphadenopathy on her PET-CT, the PET-CT scan of our case indicated an impression of peritoneal malignancy. In the first case reported by Hiensch, et al., the differential diagnosis was not able to narrow down to Mullerian duct malignancy due to the abscence of PAX-8 in their IHC stain. Furthermore, breast cancer was also one of the possible origins. Therefore, 3 courses of chemotherapy were performed prior to an exploratory laparotomy which then confirmed the diagnosis of PFTC. In our case, PAX-8 was included in the IHC stain of thoracentesis, which indicated a differential diagnosis of Mullerian duct malignancy. By combining the results of her PET-CT, we concluded a tentative diagnosis of peritoneal cancer or normal sized EOC. A diagnostic laparoscopy was first performed to evaluate the intra-abdominal condition rather than performing neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. EOC or peritoneal cancer was still highly suspected after thorough inspection of the abdomen. High grade serous carcinoma was proved by frozen section of vesicocervical reflexion tumor fragments and peritoneal nodules. Optimal debulking for Mullerian duct malignancy was achieved, and the final pathology was diagnosed as PFTC. Compared with the case reported by Hiensch, et al. both cases are clinico-radiographically occult PFTCs. Diagnosis was notoriously difficult due to both negative in clinical findings and initial radiographic images. However, by combining immunohistochemical study (positive PAX- 8, positive CK-7, and negative CK-20) of pleuracentesis, serum CA- 125 level, and PET-CT narrows the diagnosis to a gynecologic origin. Especially the IHC stain of PAX-8 had lead us to an early differential diagnosis of a Mullerian duct malignancy. The importance of PAX-8 stains also mentioned by Hiensch, et al. This illustrates the importance of comprehensive multiple diagnostic modalities in such cases.

Unlike cancers arising from the cervix, endometrium, breast and colon, where the carcinogenesis models were established because their precursor lesions are well recognized, the precursors of Highgrade Serous Carcinoma (HGSC) have been poorly understood. Recently, by advanced molecular and pathologic exams such as Sectioning and Extensive Examining of Fimbriated end (SEE-FIM), HGSC were considered to be originated from STIC or its precursor lesions including p53 signature and serous tubal intraepithelial lesion (STIL) [11-13]. Our case seems to correspond to this tubal paradigm studied by Shih, et al., therefore, the unknown origin of MPE was finally traced back to PFTC and tiny STIC lesions [13]. Furthermore, by mathematical modeling based on lesion-specific proliferative rates, the timeline of HGSC evolution could also be estimated. According to Wu, et al., the tubal paradigm of HGSC genesis starts from p53 signatures to dormant STIC, leading to proliferative STIC, and eventually becomes HGSC. It may take at least 20 years from the appearance of a p53 signature lesion to the development of proliferative STICs. The lesions would remain clinically and radiographically ‘occult’ just like our case behaved. In comparison, it takes only about 6 years for proliferative STICs to progress into HGSC (Figure 8) [12]. However, more research about mechanisms of STIC evolution and confirmation of the precancerous lesions of HGSC is needed for prevention and early detection of this hazardous Mullerian duct malignancy in the future.

Figure 8: Timeline of precancerous lesion include p53 signature, proliferative STIC evolve to high-grade serous carcinoma and transmission routes of Malignant Pleural Effusion (MPE) in reported case 1 and our presented case 2.

Conclusion

PFTCs are difficult to diagnose preoperatively due to its nonspecific symptoms and signs, which mimic those of EOC. MPE is a rare presentation of PFTCs, and it is especially difficult to diagnose in cases with both negative pathognomonic clinical findings and initial radiographic images. However, by combining multiple modalities including immunohistochemistry of pleurocentesis, serum CA-125 level, and PET-CT can narrow the diagnosis to a gynecologic origin. A final diagnosis is still made by a diagnostic laparoscopic surgery. Treatment is surgical removal of the tumor followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, then maintenance therapy with PARP inhibitor is preferable if BRCA mutation was present.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors has any financial support or relationships that may pose a conflict of interest.

References

- Alvadado Cabrero I, Stolnicu S, Kiyokawa T, Yamada K, Nikoodo T, et al. (2013) Carcinoma of the fallopian tube: Results of a multi-institutional retrospective analysis of 127 patients with evaluation of staging and prognostic factors. Ann Diagn Pathol 17(2): 159-164.

- Kalampokas E, Kalampokas T, Tourountous I (2013) Primary fallopian tube carcinoma. Eur J Obste Gynecol Repro Biol 169(2): 155-161.

- Hiensch R, Meinhof K, Leytin A, Hagopain G, Szemraje, et al. (2017) Clinically occult primary fallopian tube carcinoma presenting as a malignant pleural effusion. Clin Resp J 11(6): 1086-1090.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Papaxoinix G, Andreadis C, Papatsibas G, et al. (2009) Primary fallopian tube carcinoma: Results of a retrospective analysis of 64 patients. Gynecol Oncol 115(1): 97-101.

- Horng HC, Teng SW, Huang BS, Sun HD, Yen MS, et al. (2014) Primary fallopian tube cancer: domestic data and up-to-date review. Taiwan J Obste Gynecol 53(3): 287-292.

- Awadallah SF, Bowling MR, Sharma N, Mouan A (2019) Malignant pleural effusion and cancer of unknown primary site: a review of literature. Ann Transla Med 7(15): 353.

- Ebata T, Oluma Y, Nakahara Y, Yomota M, Takagi Y, et al. (2016) Retrospective analysis of unknown primary cancers with malignant pleural effusion at initial diagnosis. Thora Cancer 7(1): 39-43.

- Cobb LP, Gaillard S, Wang Y, Shih IM, Second AA (2015) Adenocarcinoma of Mullerian origin: review of pathogenesis, molecular biology, and emerging treatment paradigms. Gynecol Oncol Res Prac 2: 1.

- Porcei JM (2018) Biomarkers in the diagnosis of pleural diseases: a 2018 update. Therapeu Advan Res Dis 12: 1753466618808660.

- Tamam C, Tamam M, Mulazimoglu M (2016) The Accuracy of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in the Evaluation of Bone Lesions of Undetermined Origin. World J Nucl Med 15(2): 124-129.

- Visvanathan K, Wang TL, Shih IM (2018) Precancerous Lesions of Ovarian Cancer-A US Perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst 110(7): 692-693.

- Wu RC, Wang P, Lin SF, Zhang M, Song Q, et al. (2019) Genomic landscape and evolutionary trajectories of ovarian cancer precursor lesions. J Pathol 248(1): 41-50.

- Shih IM, Wang Y, Wang TL (2021) The Origin of Ovarian Cancer Species and Precancerous Landscape. Am J pathol 191(1): 26-39.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...