Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Research Article(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Hepatitis B Virus Infection among Resident Physicians and Nurses in Tertiary Hospitals in Sana’a City, Yemen Volume 5 - Issue 5

Abdul Salam Mohamed Al Makdad2, Abdulrahman Y Al-Haifi1, Hassan A Al-Shamahy3, Mohammed Kassim Salah2 and Ammar Hashim Abdullah Obaid3

- 1Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Thamar University, Damar, Yemen

- 2Department of of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Thamar University, Damar, Yemen

- 3Medical Microbiology and Clinical Immunology Department, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University, Republic of Yemen.

Received: August 28, 2020; Published: September 09, 2020

Corresponding author: Hassan A Al-Shamahy, Faculty of Medicine and Heath Sciences, Sana’a University, Yemen

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2020.05.000221

Abstract

Health care workers (HCWs) represent one of the largest groups at risk for contracting hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide.

This is due to the accidental occupational exposure to potentially infectious blood and other body fluids in the workplace. This

cross-sectional study aimed to determine the rate of exposure to HBV infection and to identify potential occupational and nonoccupational

risk factors among doctors and nurses residing in tertiary hospitals in Sana’a city. This study included 169 physicians

and nurses of whom 121 were physicians and 48 were nurses. Blood samples were collected from each one, then tested for

serological markers of HBV infections. Also, data was collected in a pre-designed questionnaire including; demographic data, the

potential occupational and non-occupational risk factors that contribute to HBV transmission. The results of the study showed that

seropositive to hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) among physicians and nurses was 5.3%, while the rate of exposure to hepatitis

B virus infection (HBcAb) was 17.8%. The rate of exposure to HBV infection (anti-HBC + HBsAg) was higher in females (33.3%)

than in males (21.4%).

The older age group was more susceptible to hepatitis B virus infection than the younger age group (P <0.05).Only 11

participants (6.5%) said they attended training courses in biosafety. Just over 45.6% indicated that they had needle injuries and

40% of sharp tool injuries while working; 61 (26%) indicated they always followed bio-safety precautions, and 74 (43.8%) said they

always wore gloves while their work. Only 32 (18.9%) of the participants received a full hepatitis B vaccination doses. Also, there

was a statistically significant relationship between cut injuries and HBV infections (P = 0.02). In addition, the highest incidence of

hepatitis B virus infection was 31.3% among nurses, while physicians had 19.8%. In conclusion, there was a high prevalence of

hepatitis B virus among doctors and nurses. Unfortunately, most workers have not received training in biosafety, and fewer than

half of the workers consistently use preventive measures such as wearing gloves during their work or taking vaccination. There is

a need to make health care workers vaccination against hepatitis B infection a consistent policy and to ensure full and consistent

compliance with standard safety procedures.

Keywords: HBV, resident, physicians, nurses, Yemen

Introduction

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most dangerous type of viral hepatitis that causes a potentially life-threatening liver infection and leads to chronic liver disease and liver cancer [1]. HBV infection is a global public health problem and the tenth leading cause of death globally [2]. According to some estimates, nearly 2 billion people are infected with the hepatitis B virus worldwide, resulting in 400 million people worldwide infected with this chronic disease. Besides, more than a million deaths due to liver disease occur in the end stage, such as cirrhosis and liver cancer (HCC) every year [3]. Hepatitis virus endemicity was estimated to be high in Yemen, wherever positive HBsAg prevalence among adults was between 8% to 20%, among infants, 4.1%, and up to 50% of the population had serological evidence of hepatitis B virus infection in old reports [4-7]. On the other hand, recent studies have indicated a decrease in the rate of HBsAg as it ranges between 0.74-2% among the general population and blood donors as well as children [8-10]. When an occupational HBV was considered, the prevalence of hepatitis B virus among 388 public health center cleaners (PHCCs) was 8.2% [11].

HBV is carried in blood and other body fluids. Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids in hospitals leaves health care workers (HCWs) at risk of infection with blood-borne viruses including hepatitis B [8,12]. In 1992, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized hepatitis B virus infection as an occupational disease for health sector workers [11]. Hospital residents, such as doctors and nurses, are at risk of infection with blood borne pathogens. This can be by a numerous procedure involving the use of sharp instruments on patients and injuries while learning new technical skill sets [11]. According to data provided by the World Health Organization, there are approximately 36 million health care workers worldwide, of whom about 3 million a year receive instrument injuries, and resulting to 2 million individuals infected with HBV, due to sharp injuries alone [13]. This cross-sectional study aimed to determine the rate of exposure to HBV infection and to identify potential occupational and non-occupational risk factors among doctors and nurses residing in tertiary hospitals in Sana’a city.

Subjects and Methods

This study included 169 randomly selected resident physician and nurses, of whom 121 were males and 48 were females and their age ranged from ≥22 to ≥38 years old with a mean age of 30 years. This study was conducted for a period of four months, starting in March 2018 and ending in June 2018 in Sana’a city. This study was performed at 3 tertiary hospitals in Sana’a city (Al-Jomhory, Al-Thorah, Al-Kuwait teaching hospitals). A consent form was done for each physicians and nurses in this study before withdrawing the blood specimens and the personal, occupational, and risk factors data were filled in a predesigned questionnaire About 4-5ml of venous blood was collected from each physicians and nurses in tubes containing separating gel and left to clot. Then all clotted samples were centrifuged at 3500 xg for 10 minutes. After that sera were divided in two labeled polypropylene screw – cap tubes and stored at -20 °C until tested for HBV markers. HBV markers were determined by using automatic sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) which intended for the use on the Elecsys 2010 analyzers machine, according to the manufacture information provided in the commercial kit manufactured by Rosh diagnostic Gmbh, Mannheim.

Statistical Analysis

Personal data and risk factors data were obtained from each subject and recorded in a pre-designed questionnaire, then the data were statistically analyzed by software version Epi Info version 6, CDC, Atlanta, USA. From two-by-two tables, the odds ratios were calculated and the value of P value was determined using the uncorrected chi square test. Fisher’s exact test was used for expected small cell sizes with a two-tailed probability value.

Results

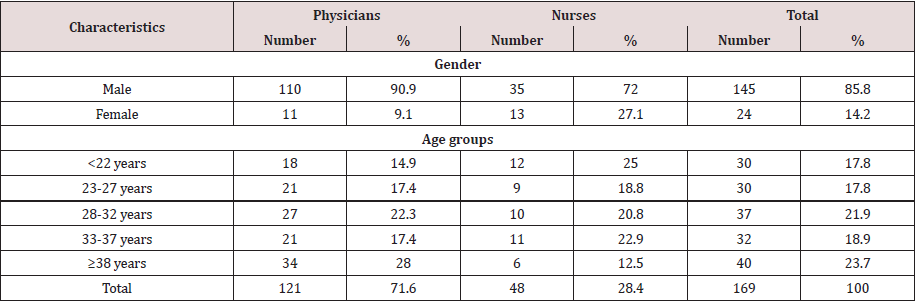

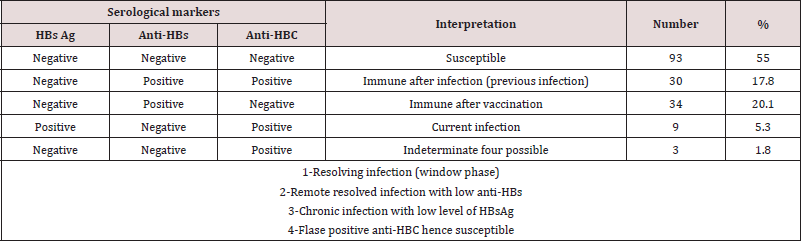

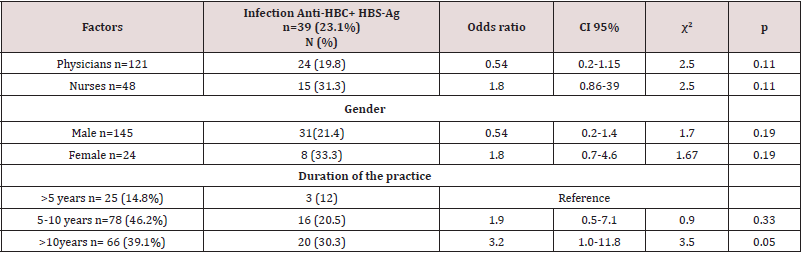

Table 1 shows the demographic and occupational characteristics of the participants in the hepatitis B epidemiological survey, most of the individuals were physicians (121) and only 48 of the individuals tested were nurses. The number of males was 145 (85.8%) and 24 females (14.2%). Table 2 represents the prevalence and interpretation of serological markers of HBV, Susceptible HCWs in which they were negative for all markers counted 55%, immune after infection in which they are positive for anti-HB core and anti- HB surface antigen counted 17.8%, while immune after vaccination HCWs were 20.1% only in which anti-HBsAg were only positive. Current infections presented in 5.3% of total tested HCWs, while 1.8% was indeterminate. Table 3 shows the adjusted and odds ratio (risk) for contracting hepatitis B virus in various occupations, gender, and duration of work, when we considered positive against HBC + HBS-Ag (23.1%) as signs of contracting for hepatitis B virus, there was a high incidence of HBV infection among nurses (31.3%) with an OR value of 1.8, compared to 19.8% for physicians but this result was not statistically significant.

Table 1: Demographic and professional characteristics of the HBV survey participants, in tertiary hospitals, Sana’a city, Yemen.

Table 2: Interpretation of serological markers of HBV among physicians and nurses in tertiary hospitals, Sana’a city, Yemen.

Table 3: The prevalent rate and odds ratio (risks) of contracting HBV for different occupations, gender, and duration of the work among physicians and nurses in tertiary hospitals, Sana’a city, Yemen.

χ2 Chi-square ≥ 3.84 (significant)

p Probability value < 0.05 (significant)

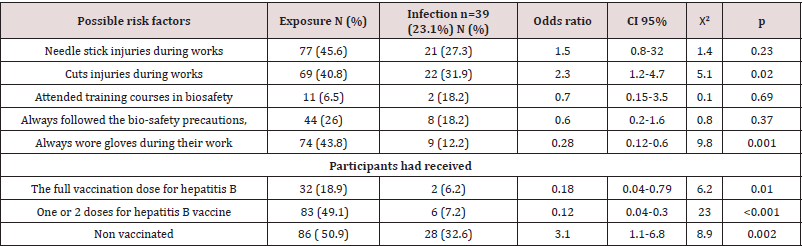

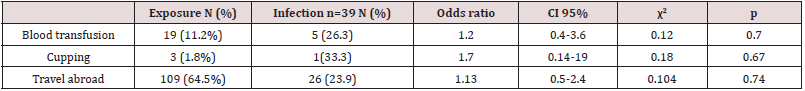

There was a higher rate of infection with female (33.3%) with an OR value of 1.8, compared to 21.4% for males but this outcome was not statistically significant. When we considered the duration of practice, there was a higher rate of contracting HBV for >10 years period (30.3%) with significant OR equal to 3.2 times, CI=1.0-11.8 times, comparing with >5 years period. Table 4 shows the occupational possible risk factors for HBV, There was a high rate of needle stick injuries (45.6%) and cuts (40.8%) among physicians and nurses. There was a higher rate of contracting HBV from occupational cuts (31.9%) with significant OR equal to 2.3 times, CI=1.2 – 4.7 times with X2=5.1 and P=0.02. There was a higher rate of contracting HBV from occupational needle stick injuries (27.3%) with non- significant OR equal to 2.5 times (P=0.23). Only 11 participants (6.5%) said they attended training courses in biosafety. Just over 45.6% indicated they had injuries and 40% of sharp tool injuries while working; 61 (26%) indicated that they always followed biosafety precautions, and 74 (43.8%) said they always wore gloves while working. Only 32 (18.9%) of the participants received a full hepatitis B vaccination dose. Table 5 shows the general risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection, and the prevalence of hepatitis B virus among individuals with a history of blood transfusion (26.3%), (OR = 1.2, p = 0.7). When cupping was considered as a risk factor, the prevalence of hepatitis B virus was 33.3%, with the risk association factor for hepatitis B contracting was equal to 1.7 and this result was not significant (p = 0.67). The prevalence rate among individuals with a history of traveling abroad was 23.9% with an OR = 1.13 (p = 0.74).

Table 4: Occupational possible risk factors for HBV among physicians and nurses in tertiary hospitals, Sana’a city, Yemen with previous and current HBV infection

χ2 Chi-square ≥ 3.84 (significant)

p Probability value < 0.05 (significant)

Table 5: General risk factors of contacting HBV among physicians and nurses in tertiary hospitals, Sana’a city, Yemen, with previous and current HBV infection.

χ2 Chi-square ≥ 3.84 (significant)

p Probability value < 0.05 (significant)

Discussion

The crude rate of HBs Ag that indicates the current infection

with the hepatitis B virus among our physicians and nurses is 5.3%

(Table 2). This rate is similar to the rate of the general population in

various regions in Yemen, including the city of Sana’a before 2004

[4-6]. However, our rate is five times higher than the rate that was

recently reported in the general population in different regions of

Yemen including adults and children, which ranges between 0.7-

2% among the general population [10,14,15]. This rate is similar

to the rate for dental clinics in the city of Sana’a, where the current

serological prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection was 6.1% [16].

The high rate of hepatitis B among HCWs in our study is similar

to the rate mentioned in previous epidemiological studies among

HCWs and is higher than the rate in the general population, and

this finding confirms that hepatitis B is an important occupational

hazard for health care workers [17,18]. In some studies, it has

been shown that HCWs have up to four times the risk of developing

hepatitis B virus [19]. As the main risk factor for infection with

hepatitis B virus for HCWs is direct contact with infectious

substances, especially blood infected with HBV or via a needle

stick injury with body fluids contaminated with hepatitis B virus

as described by Abbas et al. [16] In Yemen and Pellissier et al. [20]

In Nigeria.

In particular, recapping of hollow-bore needles appears to

increase the risk of needle stick injuries [21]. Other studies have

reported a lack of awareness of HBV among HCWs; consequently,

proper precautions (e.g., use of disposable gloves) against bloodborne

infections are lacking in these workers [1]. This observation

is consistent with other studies demonstrating that untrained

individuals are more likely to be exposed to HBV infection [22].

The prevalence of current HBV infection among female health care

workers in our study was 7.8%; prevalence of life time exposure

to hepatitis B virus was 33.3%; higher than that of males as the

current hepatitis B infection was 4.2%; the prevalence of a lifetime

exposure was 21.4%. Also the associated odds ratio HBV infection

in females was 1.8 times, compared to 0.54 for males (Table 3).

This result differs from the common pattern of HBV among HCWs

in most reports where the rate of HBV is almost the same in both

sexes, [17.23] while this result is similar to that reported by Abbas

et al. [16] in Yemen, where the infection rate is higher among female

HCW than male HCWs. This result might be explained by that female HCWs exposed more than male HCWs to the risk factors of

contracting HBV [23,18].

The results of our study indicate that the prevalence of HBV

depends on the period of practice in the profession, where rates

increase with increasing duration of practice, for example the

rate of antibodies to HBs + HBs Ag for> 5 years was 12% and

this percentage increased for a period of 10 years to 33.3%, with

significant associated OR equal to 3.2 times (pv=0.05) (Table 3). This

results is similar to studies that covered wider range of duration of

practices in several risk HCW groups including physicians, nurses

and dentists which indicated that the prevalence of HBV is duration

practice dependent, in which it was increased with increasing

duration of practice HCWs occupation age [16,17,21,23]. This

relation could be explained by various reasons. One explanation

could be that there is a more or less constant risk of exposure during

life time and therefore the Hepatitis B prevalence increases with

time of exposure. We cannot rule out, that the risk of transmission

might have changed over time due to increased awareness and

precautions like wearing of gloves and use of safety needles. On

the other hand the finding, that long occupational exposure in

healthcare services increases the risk of acquiring HBV infection, is

consistent with other studies [17,23].

The risk of acquiring HBV from a needle stick injury ranges from

1% to 6% (source patient HBsAg-positive, HBeAg-negative) to 22%

to 40% (source patient HBsAg-positive, HBeAg-positive) [24]. The

risk of non-percutaneous exposure may account for a significant

proportion of HBV transmission in the healthcare setting. Hepatitis

B virus can survive in dried blood for up to a week and thus may be

transmitted via discarded needles or fomites, even days after initial

contamination. Indeed, many healthcare workers infected with

HBV cannot recall an overt needle stick injury, but can remember

caring for a patient with hepatitis B [25]. There was a significant

risk of infection with hepatitis B virus in our HCWs with history of

recent accident cut during practices where the OR was 2.3 times

and this outcome was important where p = 0.02 (Table 4). This

finding shows that our medical professionals may be more likely

to get hepatitis B infection in hospitals because they are learning to

do procedures and may be less cautious than other health workers

in other countries. They are also less likely to practice universal

precautions and are more likely to sustain needle stick injuries due

to inexperience.

The present study showed that Medical workers (physicians

and nurses) of face a high risk of blood-borne infections through

blood exposures incidents. The prevalence rate needle stick was

45.6%. In a study conducted in Australia, an average of 3.0 percutaneous

exposures (PCE) was reported among physicians

annually [24]. Difference in exposure rates among different

studies may be due to different subjects (job categories), sampling methodologies. Medical workers in Yemen represent the most staff

and less experienced, and hence longer working hours and greater

probability of blood exposure. A study was conducted among

Australian medical workers in whom 13.8% had suffered a total of

41 needle stick and sharps injuries (NSI) incidents [24]. In 2003 a

study was conducted in Missouri, USA, in which 43 out of 224 HCWs

(19.2 %) reported needle stick injuries [26]. Needle stick injuries

during internship were reported by 61.9% (438/708) of Taiwanese

nurses [27]. In the above-mentioned studies, it seems that in the

more developed countries, the number of blood-exposure accidents

lends to be lower. The overall socio-economic status and knowledge,

and adoption of necessary precautions, and safety guidelines have

led to lower exposure rates.

Presently in Yemen, efforts aimed at controlling hepatitis

B viral infection remain feeble. There are no policies at both the

National and Institutional levels on vaccination of high risk groups

like health care workers and medical students. The present study

was carried out also to determine the hepatitis B vaccination

rate among medical workers in hospitals who could readily come

in contact with infected body fluids from patients and hospital

equipment during their clinical workers. This will generate

information required to advocate for pre-vaccination policies for

all high risk groups. Also, immunization against hepatitis B viral

infection has assumed a primary role in the control of hepatitis B

infection. Hepatitis B vaccine has been found to effectively reduce

the prevalence of HBV infection [8,10]. Several studies [8,9,18]

demonstrated that introduction of compulsory HBV vaccination

contributes in decreasing HBV incidence rates. After a standard

3-dose vaccination regime at 0, 1, and 6 months, the rate of

response on the basis of an anti-HBsAg titer of ≥10 mIU/mL is

90%–95% [18,28,29]. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of

health care workers including physicians and nurses do not receive

HBV immunization, and remain susceptible to HBV infection [28].

Vaccination coverage of the medical workers in the present work

was 49.1% (one or more doses) against HBV and only 20.1% of the

total were immune after vaccination (Table 4). Among Taiwanese

nurses, vaccination against hepatitis B virus (HBV) was lacking

in 47.6% [27]. However, the effectiveness of the vaccination is

an important factor; also the completed doses should be strictly

followed. In our study we found that the lowest vaccination rate

(25%) (Table 4) was among the nurses while vaccination rate

among physicians was higher (58.7%).

Also the study findings showed that 6.2% of all vaccinated

individuals had full vaccine doses were regarded as infected with

HBV infection (HBsAg+Anti-HBC positive) (Table 4). Different

findings were reported in Iran among vaccinated adults, where a

high protective anti-HBs response rate was found among vaccinated

adults (97.4%) [29]. This difference in findings could be attributed

to a different response in the primary course of vaccination, different age groups, or to the different degrees of exposure to natural

boosters and nutritional status and socioeconomic factors, race

factors, or the type of vaccines used [30]. In this study, HB surface

antigen was obtained among the whole studied HCWs (vaccinated

and non-vaccinated), but due to the lack of serological data, either

before or after vaccination, it was impossible to conclude whether

these HCWs were already infected at the time of vaccination or

infected subsequently. In the present study it was found that the

frequency of HBsAg+anti-HBc positivity among the whole HCWs

were 23.1% (Table 2), which was lower among full dose vaccinated

(6.2%) when compared with the rate of the non-vaccinated HCWs

(32.6%) (Table 4). This result indicate absent of HBV vaccine is

risk factor for contracting HBV infection and vaccination for HBV

is protective measures against HBV infection as described by most

previous reports [9,10,18,31].

Also one of our aim was to determine the non-occupational risk

factors of contracting hepatitis B virus among our HCWs. To achieve

this aim, odds ratio of contracting HBV infection, and its confidence

interval was calculated, and their significant also was determined

by X2 and p value (Table 5). There was no significant association

between HBV contract with history of blood transfusion, cupping

and/or travel abroad, and this different with findings among

different population groups in Yemen by Al-Shamahy et al. [4],

and Scot et al. [6] that prior factors were significant risk factor for

hepatitis virus infections. Our results were also different from those

conducted in Syria, where the previous factors were the risk factors

for hepatitis B virus infection among the general population and

risk groups in Syria [32].

Conclusion

In conclusion high prevalence rates of HBV occurred among physicians and nurses. Unfortunately; most of the workers did not take training on biosafty, and less than half of the workers use protective measures consistently as always wore gloves during their work or vaccination. There is needed to make vaccination of health care workers against HBV infection a firm policy and ensure complete and consistent adherence to work standard safety measures. Also further research is needed to clarify the results of the current study.

Author’s Contribution

This research work is part of a research work under the supervision of Hassan Al-Shamahy. The field, and laboratory works of the research was done by the corresponding author, and the forth author. The first, second, and third authors supervised the work and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Sana’a for financial support

Conflict of Interest

“There is no conflict of interest related to this work.”

References

- Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST (2012) Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 30: 2212.

- Yousafzai MT, Qasim R, Khalil R (2014) Hepatitis B vaccination primary health care workers in Northwest Pakistan. International Journal of Health Sciences 8(1): 68-76.

- Khedive A, Sanei E, Alavian SM (2013) Hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) mutations are rare but clustered in immune epitopes in chronic carriers from Sistan-Balouchestan Province. Iran. Arch Iran Med 16(7): 385-389.

- AL-Shamahy H (2000) Prevalence of Hepatitis B surface antigen and Risk factors of HBV infection in samples of healthy mothers and their infants in Sana'a, Yemen. Ann Saudi Medicine 20: 464-467.

- Al-Shamahy HA, IA Rabbad, A Al-Hababy (2003) Hepatitis B virus serum markers among pregnant women in Sana'a, Yemen. Ann Saudi Med 23: 87-89.

- Scott DA (1990) A sero epidemiological survey of viral hepatitis in Yemen Arab Republic. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 84(2): 288-291.

- Al-Waleedi AA, Khader YS (2012) Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections and associated factors among blood donors in Aden city, Yemen. Eastern Med Health J 18(6): 1-7.

- Al-Shamahy HA, Jaadan BM, Al-Madhaji AG, Al-Fraji BBM, Ajrah MA, et al. (2019) Prevalence and potential risk factors of hepatitis B virus in a sample of children in two selected areas in Yemen. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 4(3): 18-22.

- Al-kadassy AM, Al-Shamahy HA, Al-Ashiry AFS (2019) Sero-epidemiological study of hepatitis B, C, HIV and treponema pallidum among blood donors in Hodeida city- Yemen. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 4(2): 40-44.

- Al-Shamahy HA, Samira H Hanash, Iqbal A Rabbad, Nameem M Al-Madhaji (2011) Hepatitis B Vaccine Coverage and the Immune Response in children under 10 years old in Sana'a Yemen. SQU Med J 11(1): 77-82.

- AL-Marrani WHM, Al-Shamahy HA (2018) “Prevalence of HBV and HCV; and their associated risk factors among public health center cleaners at selected public health centers in Sana’a city-Yemen”. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 3(5):1-5.

- Franco E, Bagnato B, Marino MG (2012) Hepatitis B: Epidemiology and prevention in developing countries. World J Hepatol 4(3): 74-80.

- Elseviers MM, Arias-Guillén M, Gorke A (2014) Sharps injuries amongst healthcare workers: review of incidence, transmissions and costs. J Ren Care 40: 150-156.

- Murad EA, Babiker SM, Gasim GI, Rayis DI, Adam I (2013) Epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in pregnant women in Sana’a, Yemen. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13: 113-127.

- Nabehi BAH, Al- Shamahy H, Saeed WSE, Musa AM, El Hassan AM, et al. (2018) Sero-molecular epidemiology and risk factors of viral hepatitis in urban Yemen. Int J Virol 11: 133-138.

- Abbas Al Kasem MA, Al-Kebsi Abbas M, Madar Ebtihal M, Al-Shamahy Hassan A (2018) Hepatitis B virus among dental clinic workers and the risk factors contributing for its infection. On J Dent Oral Health 1(2): 1-6.

- Jha AK, Chadha S, Bhalla P, Saini S (2012) Hepatitis B infection in microbiology laboratory workers: prevalence, vaccination, and immunity status. Hepat Res Treat pp. 520362.

- WHO (2016) Health Care Worker Safety/AIDE-Memoire for a strategy to protect health workers from infection with blood borne viruses.

- Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT (2015) Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 386: 1546.

- Pellissier G, Yazdanpanah Y, Adehossi E, Tosini W, Madougou B, et al. (2012) Is universal HBV vaccination of healthcare workers a relevant strategy in developing endemic countries? The case of a university hospital in Niger. Plosone 7: e44442.

- Salehi AS, Garner P (2010) Occupational injury history and universal precautions awareness: a survey in Kabul hospital staff. BMC Infect Dis 10: 19.

- Ghany MG, Perrillo R, Li R (2015) Characteristics of adults in the hepatitis B research network in North America reflect their country of origin and hepatitis B virus genotype. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 183-192.

- Noubiap JJN, Nansseu JRN, Kengne KK, Wonkam A, Wiysonge CS (2014) Low hepatitis B vaccine uptake among surgical residents in Cameroon. Int Arch Med 7: 11.

- Smith DR, Leggat PA (2005) Needlestick and shaips injuries among Australian medical students. J UOEH 27: 237-242.

- Sepkowitz KA (1996) Occupationally acquired infections in health care workers. Part II. Ann. Intern. Med 125: 917-928.

- Patterson JM, Novak CB, Mackinnon SE, Ellis RA (2003) Needle stick injuries among medical students. Am J Infect Control 31(4): 226-230.

- Shiao Judith SC (2002) Student Nurses in Taiwan at High Risk for Needle stick Injuries. Annals of Epidemiology 12(3):197-201.

- Zanetti AR, Van Damme P, Shouval D (2008) The global impact of vaccination against hepatitis B: a historical overview. Vaccine 26(49): 6266-6273.

- Guo Y, Hui CY (2009) Pilot-scale production and quality control of multiepitope hepatitis B virus DNA vaccine. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 29(1): 118-120.

- Greengold B, Nyamathi A, Kominski G (2009) Cost-effectiveness analysis of behavioral interventions to improve vaccination compliance in homeless adults. Vaccine 27(5): 718-725.

- Jung M, Kuniholm MH, Ho GY (2016) The distribution of hepatitis B virus exposure and infection in a population-based sample of U.S. Hispanic adults. Hepatology 63: 445-452.

- Moukeh G, Yacoub R, Fahdi F (2009) Epidemiology of hemodialysis patients in Aleppo city. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 20(1): 140-146.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...