Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Mini Review(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Entrapment of Closed Suction Drain after Robotic-Assisted Total Knee Arthroplasty: A rare entity Volume 5 - Issue 3

Babaji Thorat DNB*, Avtar Singh MS, Rajeev Vohra MS and Anil Naikawadi DNB

- Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Amandeep Hospital, Amritsar, India

Received:July 25, 2020; Published: August 04, 2020

Corresponding author: David Jeong, Department of Surgery, Trinity School of Medicine, Ribishi, Saint Vincent, USA

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2020.05.000214

Abstract

The postoperative use of surgical drains in a joint replacement surgery still remains controversial. Breaking of the surgical drain or retained drain fragments is an uncommon but preventable event. Moreover, entrapment of surgical drain in between the femoral component and under the surface of the patella is relatively rare. It can be stressful for both the patient and the surgeon and may lead to serious consequences such as psychological stress to the patient, the possible need for another surgery for removal of drain fragments, poor clinical outcome. In this report, we present a case of entrapment of surgical drainage tube in the patellofemoral joint space in a 60-year-old female patient who underwent Robotic-Assisted Total Knee Arthroplasty (RATKA). This report emphasizes the need for the surgeon to express caution when using surgical drain postoperatively as well as discusses the challenges in management as well as an overview of various techniques available in the recent literature for the prevention and removal of these retained drains.

Keywords: Closedsuction drain, surgical drain, entrapment, Total Knee Arthroplasty, retained drain

Introduction

Despite recent advances and benefits of closed surgical

drains, their use postoperatively remains controversial due to the

associated potential risks[1]. Breaking of the surgical drain or

retained drain fragments in orthopaedic surgery is an uncommon

and even more controversial but preventable complication, owing

to the increased awareness due to availability of previous reports

of retained surgical drains in the orthopaedic literature. However,

entrapment of a closed surgical drainage tube in joint space

between the femoral component and under the surface of the

patella is a relatively rare event after Robotic-Assisted Total Knee

Arthroplasty (RATKA) [2].The common causes include suturing the

drain during surgical wound closure or breakage of the drain at the

weakest point [3]. This can be stressful to both surgeon and patient,

moreover, if undiagnosed, it can lead to serious consequences such

as infection, decreased clinical outcome, psychological stress to the

patient, the possible need for another surgery for the removal of

drain and increased financial burden[1,4,5].

Additionally, it can also result in delayed rehabilitation, late

return to activity, poor clinical outcome and also a reason for

litigation against the orthopaedic surgeon [6]. We have discussed

a case of entrapment of surgical drain in Total Knee Arthroplasty in

a 60-year-old female patient along with challenges in management

as well as an overview of various techniques available in the recent

literature for the prevention and removal of these retained drains.

The purpose of this review is making aware the surgical team

about methods to avoid suturing in drains as well as to remove

the

Case presentation

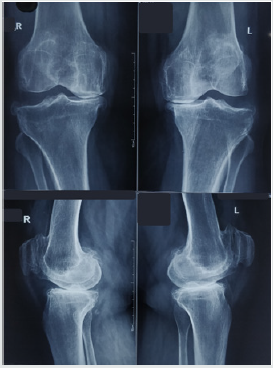

An obese (Body Mass Index- 30.6) 60-year-old female suffering from osteoarthritis of both knee joints successfully underwent simultaneous bilateral cruciate-retaining cemented RATKA in our institute (Figure 1). A closed suction drain (Romovac suction drain, No. 12, Romsons International, Noida, India, Ltd) was placed in the lateral gutter of the knee under direct visualisation at the end of the arthroplasty procedure during wound closure. Postoperative radiographs showed satisfactory femoral and tibial component positioning and surgical drain in the lateral gutter. Physiotherapy and knee range of motion exercise were started on the same day. On the 2nd postoperative day, a significant resistant was felt when an attempt was made by the surgical resident for drain removal during first dressing. The surgical drainage tube was presumed to have been sewn into the fascial layer during the closure of the wound. Hence, we ordered a repeat radiograph of the knee which revealed surgical drainage tube have migrated to get entrapped in joint space between the femoral component and under surface of the patella (Figure 2). We assumed that the drain may have caught in between the femoral implant and under the surface of the patella during knee exercises.

Figure 1: Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showing severe osteoarthritis of both knees and postoperative radiographs showing satisfactory component positioning and alignment with suction drain in lateral gutter.

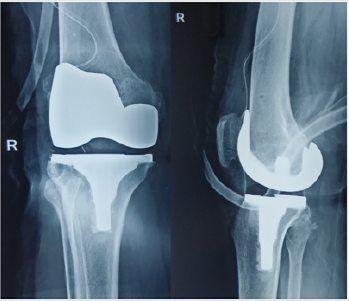

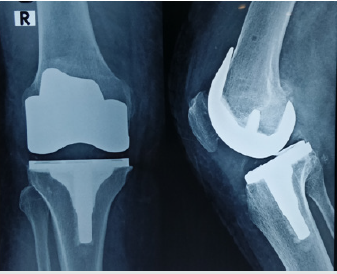

We, initially, tried removing the drain by using various gentle noninvasive/nonsurgical techniques described in the literature, but, were unsuccessful because of associated pain. We counselled the patient for invasive procedures for drain removal, however, she was not willing to undergo another surgical procedure. The next day, with patient under sedation, we tried for drain removal by applying gentle traction along with simultaneous knee flexion and extension movements. We were able to remove the whole of the drain without any inadvertent event. On examination, the removed drainage tube was found to have had signs of crushing without any punctures or breakage (Figure 3) which suggest entrapment in joint space between the femoral implant and patellar under surface. After drain removal, the patellar tracking and knee range of motion was normal without any instability, mechanical blockade or locking symptoms. Repeat knee radiographs confirmed the complete removal of the drain (Figure 4).

Figure 2:Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showing drain from lateral gutter migrated to get entrapped into the joint space between the femoral component and under surface of the patella.

Figure 3: Photograph of the drain confirming complete removal and showing signs of crushing of drainage tube without any punctures or breakage.

Figure 4: Repeat radiographs of knee confirming the complete removal of the drain on anteroposterior and lateral view.

Her surgical wound healed without any complication and the remaining postoperative stay in the hospital was uneventful. She was discharged on 4th postoperative day. She regained satisfactory pain-free range of motion at the right knee joint and resumed her daily activities with excellent functional outcome. At 1-year followup, she reported good outcome with painless, well-functioning knee, and knee range of motion of 0-1100 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: At 1-year follow-up, she reported good outcome with painless, well-functioning knee, and knee range of motion of 0-110 degree.

To our knowledge, this is the first known reported case of entrapment of drain in between the femoral component and under the surface of the patella after RATKA.

Discussion

Use of closed suction drains after Total Knee Arthroplasty

(TKA) is an age-old practise among orthopaedic surgeons and has

its advantages and disadvantages. However, the literature is divided

on its use, and this practice is questioned in multiple previous

studies and remains controversial[2,7]. In this case report, we

have illustrated the potential risk and subsequent complications

of leaving the drain inside the joint cavity after joint replacement

surgery. The use of closed suction drain postoperatively is aimed to

minimise risk with the advantages that include reduced hematoma

or seroma formation, soakage and ecchymosis, thus, less need for frequent change of dressing. But, the effect on wound healing and

infection is still debatable[7,8]. Disadvantages include irritating

pain, increased blood loss, risk of neurovascular injury and

infection; an additional procedure for its removal if the surgical

drainage tube gets sutured or retained within the wound or caught

directly between the components or joint cavity[2].

The probable reasons for drain breakage inside the

wound include weakening of drain material by body fluid at

body temperature, the pattern of distribution of perforations,

manufacturing method used for making drain perforations, drain

adhered to soft tissues due to the maintenance of high negative

pressure, or drain sutured within the soft tissues of the wound

during the closure. And sometimes, the underlying cause cannot be

ascertained during surgical removal[9]. Few studies have reported

that the drain related complications such as entrapment or breakage

are underreported in the literature and likely to need additional

intervention for drain removal[6,10].While, some authors report

that retained drains in the soft tissues do not affect the long term

outcome. However, the drains inside the joint cavity can lead to

serious complications such as pain, infection, polymeric debris,

articular cartilage injury, foreign body granuloma formation and

impairing the normal range of motion. Until, there is no consensus

or reviews about the removal of a retained or entrapped drain

available in the orthopaedic literature, to our knowledge[2,11].

Arthroscopic drain removal can be an easy, less invasive

alternative to conventional open surgical techniques. The

advantages are decreased surgical morbidity, and facilitating

postoperative recovery and rehabilitation[12].The additional

surgical procedure needed for drain removal or complications

due to retained drain may lead to medico-legal litigation against

the surgical team. Appropriate patient counselling regarding the

complication and prompt management can be helpful to avoid

medico-legal implications against the surgical team. In our institute,

we follow a standard protocol of documenting the number of

drain holes inside the wound which have helped us to ascertain

that the drain is removed completely without any additional

procedure. In our case, we were fortunate that timely counselling,

prompt removal of drain without any need of additional invasive

procedure, patient’s good clinical recovery without any of the

above-mentioned complications were the favourable factors that

helped us to circumvent a medico-legal issue.

We were unable to ascertain the exact mechanism about how

the drain got entrapped between the femoral implant and patella.

However, the possible explanation is that the drain became stuck

in between the femoral implant and under the surface of the

patella during exercises. Numerous techniques are described for

prevention, confirmation and management of retained drains

in the literature of orthopaedic surgery and among many other

specialities that regularly use surgical drains.

If the drain is secured with a skin suture, the suture should be cut first before removal of the drain. Gentle force tolerable to the patient should be applied for drain removal. Comparison of pre and post drain removal radiographs can be helpful to confirm about breakage or retained drain fragments while using non-invasive procedures for drain removal. Postoperatively, if resistance is encountered during the removal of drain, the possibility of that the drain caught in the joint space or between the components should be considered. Nonsurgical manoeuvre such as attempts for removal of the drain with gentle knee range of motion or traction can prevent further need for additional surgical intervention. At the same time, it also expresses caution while attempting removal of drain and the need to avoid repeated non-invasive manoeuvres for drain removal. Drainage tube should be inspected upon removal and compared against the documented number of drain holes inside the wound as mentioned in the surgical notes at the end of the surgery. This case report emphasizes the deploying of a standard protocol for surgical drain insertion and removal concerning postoperative care in joint replacement surgery.

Conclusion

Despite being an uncommon event, entrapment or retained surgical drains in TKA are a completely preventable complication and should not occur. The consequences include stress to the patient, delayed rehabilitation, poor clinical outcome and need for an additional invasive procedure for drain removal. The incidence can be significantly reduced by consistently following a standard operative protocol employing the described preventive techniques.

Clinical message

A standard protocol should be followed during insertion and removal of the surgical drain with caution to prevent an easily avoidable complication such as breakage or retention of drain fragments. Furthermore, the surgeon should maintain a high index of suspicion for early detection of iatrogenic drain related complications when a patient continues to complain unexplained pain over the operated site.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that our manuscript is an original publication and the data is case report is real. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Declarations of Interest

None.

Source of Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit sectors.

Acknowledgments

“The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient informed consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/ have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.”

References

- Cobb JP (1990) “Why use drains?” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 72(B): 933-935.

- Jaafar S, Vigdorchik J, Markel DC (2014) Drain technique in elective total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics 37(1): 37-39.

- Zeide MS, Robbins H (1975) “Retained wound suction-drain fragment. Report of 7 cases.” Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases 3(2): 163-169.

- Varley GW, Milner S (1994) “Wound drains in proximal femoral fracture surgery. Report of a randomised prospective trial of 177 patients.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 76(2): 147-148.

- Browett JP, Gibbs AN, Copeland SA, Deliss LJ (1978) “The use of suction drainage in the operation of meniscectomy.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-Series B 6(4): 516-519.

- Hak DJ (2000) Retained broken wound drains: A preventable complication. J Orthop Trauma 14(3): 212-213.

- Si HB, Yang TM, Zeng Y, Shen B (2016) No clear benefit or drawback to the use of closed drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17: 183.

- Parker MJ, Roberts CP, Hay D (2004) Closed suction drainage for hip and knee arthroplasty. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86(A): 1146-1152.

- Gheorghiu D, Cowan C, Teanby D (2015) Retained surgical drain after total knee arthroplasty: an eight-year follow-up: a case report. JBJS Case Connect 5(3): e63.

- Lazarides S, Hussain A, Zafiropoulous G (2003) Removal of surgically entangled drain: A new original non-operative technique. Int J Curr Med Sci Pract 10(1): 63-64.

- Gaines RJ, Dunbar RP (2008) The use of surgical drains in orthopedics, Orthopedics 31: 7.

- Kao FC, Hsu KY, Shih HN, Cheng CY, Tsai YH, et al. (2002) Arthroscopic extraction of a drainage tube: solution for a troublesome problem. Arthroscopy 18(7): E36.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...