Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1306

Research Article(ISSN: 2644-1306)

Interactions between Measles, Mumps and Rubella (Mmr) Vaccines and Atopic Diseases in Children Volume 1 - Issue 1

Jacques Lukenze Tamuzi*1 and Jonathan Lukusa Tshimwanga2

- 1Community Health Division, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Matieland, South Africa

- 2Division of Family medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Matieland, South Africa

Received: February 15,2018; Published: February 27,2018

*Corresponding author: Jacques Lukenze Tamuzi, Community Health Division, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Matieland, South Africa

DOI: 10.32474/TRSD.2018.01.000101

Abstract

Background: Epidemiologic data on atopic diseases are scared. Different studies have shown that the burden of atopic diseases is varying in space and time. Several factors are impacting on epidemiology of atopic in children. Among them, MMR vaccination has been a topic of divergences.

Objective: To establish whether the MMR vaccination may influence the risk of atopic diseases in children.

Methods: We conducted electronic search terms included MESH or key words with "Atopic diseases” and "MMR vaccination” and “Children”. Databases for peer-reviewed articles included Pub Med, CENTRAL, Scopus and CINAHL Plus. Additionally, Grey literature was obtained from Google and WHO database.

Main results: Among 304 potentially relevant articles identified, 8 peer-reviewed articles met the inclusion criteria. Due to the lack of standardized reporting of different outcomes and different study designs, we reported the results narratively based on P-value and 95% CI. We found three studies that demonstrated that MMR vaccination increased the fold of asthma in children (P<0.05). In contrast, two studies have approved that MMR vaccination is benefit in preventing asthma in children. MMR vaccination decreases asthma respectively by OR 0.36 95%CI (0.14-0.91) and OR 0.96 95% CI (0.76-1.21). Two studies reported MMR vaccination increase the eczema OR in two studies with respectively OR: 1.77 95% CI (1.20-2.61) and OR 1.86 95%CI (1.25-2.79). On the other hand, three studies revealed that MMR vaccination did not have any effect on atopic eczema with respectively P=0.830, OR 0.94 95% CI (0.77-1.15) and P=0.90.

Conclusion: Based on the variability between studies, we hypothesize that judging the association between MMR vaccination and atopic diseases could not be fruitful in understanding different mechanisms. In this context, we suggested the interactions between Gene-environment MMR vaccination and atopic diseases that could clarify divergences between the results.

Keywords: Atopic diseases; MMR vaccination; Children

Background

The word atopy (Greek: atopia, out of place) refers in accordance with an inherited tendency to produce immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies in response to small amounts of common environmental proteins such namely pollen, house dust mite, and food allergens [1]. The presence of atopy in an individual is associated with an increased risk of developing atopic diseases among which atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhino-conjunctivitis/hay fever (and food allergy) [2]. However, atopy can be present in the form of asymptomatic sensitization to one or more allergens, which means that an individual with confirmed allergic sensitization does not exhibit clinical allergy [2]. Epidemiologic data on atopic diseases are scared. Different studies have shown that the burden of atopic diseases is varying in space and time. Secular trends in atopic diseases have been studied worldwide. The rise in disease occurrence was particularly apparent between the 1960s and the 1990s, after which the rise evened out. For example, in Australia the occurrence of asthma in schoolchildren rose up from 12.9 to 38.6% between 1982 and 1997, and the prevalence of hay fever increased from 22.5 to 44.0% [1].

In Denmark, the prevalence of atopic dermatitis augmented from 17.3 to 27.3% among children aged 7-17 years between 1986 and 2001, and the prevalence in children living in Scotland increased from 5.3 to 12.0% between 1964 and 1986 [1-3]. In many resources limited countries, atopic diseases occurrence have also seen a marked increase. For example, in South African children the prevalence of eczema increased from 11.8% in 1995 to 19.4% in 2001 [1-4]. Only atopic dermatitis also called atopic eczema affects 1-3% of adults worldwide. Fifty percent of all those with atopic dermatitis develop other allergic symptoms within their first year of life and probably as many as 85% of the patients experience an onset below 5 years of age [5]. Patients generally outgrow the sickness in late childhood as around 70% over the patients with a disease onset during childhood have a spontaneous remission before adolescence. In addition, about 75% of children with atopic dermatitis develop allergic rhinitis and more than 50% develop bronchial asthma [2].

In reality, several elements affect the immune system in early life. Among these factors, routine mass immunization of children against a variety of infectious diseases has been incriminated to rise up the risk of atopic diseases. This topic is subject to contradiction between authors. In effect, immunization in children could directly stimulate TH 1-like immunity or indirectly prevent such immune responses by reducing the occurrence of some infections [6]. The immune response observed during the course of atopic diseases is characterized by a biphasic inflammation. A Th2-biased immune response (IL-4, IL-13, TSLP and eosinophils) is prior in the initial and acute phase of atopic diseases, while in chronic atopic diseases, a Th1/Th0 dominance has been described (IFN-y, IL-12, IL-5 and GM-CSF) [5-7]. Viral infections promote a Th1-biased immune response and live viral vaccines, such as those for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), may promote a similar response [8,9]. This is supported by the observation of high levels of the Th1 signature cytokine IFN-c and low concentrations of the Th2 signature cytokine IL-4 in children after measles vaccination [9-11]. Th2 associated first type or immediate hypersensitivity reactions involve immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated release of histamine and other types of mediators from mast cells and basophiles Type I reactions underlie the following atopic disorders: allergic asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis [11]. In spite of that, immunologic mechanisms could not explain clearly the interactions between MMR vaccination and atopic diseases which are subject to controversy and no consensus. Reviewing the literature, MMR vaccination could increase, maintain or decrease the likelihood of developing atopic diseases in children. As proven by immunologic mechanism, MMR vaccination may stimulate different pathways and induce atopic disorders. We reviewed different studies in the field of MMR vaccination and atopic diseases and suggest some hypotheses that could highlight the discrepancy in different studies.

Objective

The main objective was to study whether the MMR vaccination may influence the risk of atopic diseases in children.

Methods

We conducted electronic search terms included MESH or other associated terms with 'Atopic diseases" and "MMR vaccination" and "Children". Databases for peer-reviewed articles included Pub Med, CENTRAL, Scopus and CINAHL Plus. Furthermore, Grey literature was obtained from Google and WHO database. Article citations were organized uploaded and reviewed using the review manager (Revman) from their respective databases. The title, author, journal and year of publication were then exported to an excel spreadsheet for title and abstract review. Articles were screened by JLT and JLT to determine whether they included relevant information. JLT and JLT assessed the quality of quantitative data from studies with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Observational studies were assessed with Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. The following domains were used for bias assessment: -is the case definition adequate? - Representativeness of the cases -Selection of controls -Definition of controls -Comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis -Ascertainment of exposure -Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls reporting, external validity, bias, confounding and power [12].

Results

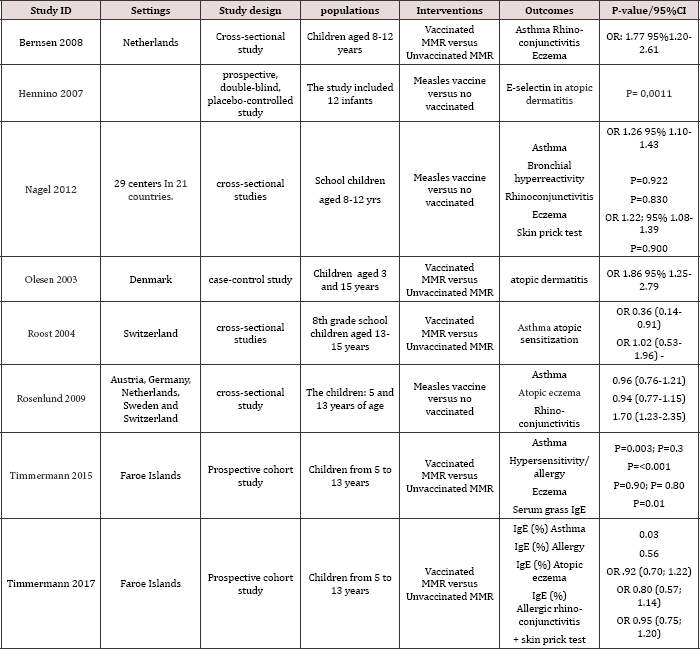

We identified 304 potentially relevant articles. A total of 8 peer- reviewed articles met the inclusion criteria and were included for further analysis. Due to the lack of standardized reporting of different outcomes, we could not undertake meta-analysis. Instead, we categorized studies by their settings, designs, interventions, outcomes and P-value/95%CI (Table 1). We included different study designs among which four cross-sectional studies, three prospective cohort studies and one case control study. We found three studies have shown that MMR vaccination increased the fold of asthma in children. The results were statistically significant with P-value<0.05 or the OR was above 1, the 95%CI did not include the null value [9,13-14]. MMR vaccination increase the eczema OR in two studies with respectively OR: 1.77 95% CI (1.20-2.61) and OR 1.86 95%CI (1.25-2.79) [13-15]. Children that received MMR vaccination were likely to have rhino-conjunctivitis in two studies with OR: 1.77 95%CI (1.20-2.61) and OR 1.70 95% (1.232.35) [13-16]. MMR vaccination increased serum IgE in asthmatic children (P=0.03) [17], however, serum IgE remain normal in both atopic eczema and rhino-conjunctivitis [17]. Only one study used serum selecting outcome in children with atopic dermatitis. Serum selecting was higher in MMR vaccination group than MMR unvaccinated group (P=0.0011). In contrast, two studies have approved that MMR vaccination is benefit in preventing asthma in children [6-16]. MMR vaccination decreases asthma occurrence respectively by OR 0.36 95%CI (0.14-0.91) and OR 0.96 95%CI (0.76-1.21). But, the last 95%CI was not statistically significant. Three studies revealed that MMR vaccination did not have any atopic eczema with respectively P=0.830, OR 0.94 95% CI (0.77-1.15) and P=0.90. In two studies [17] that analyzed skin prick test, MMR vaccination versus MMR unvaccinated did not shown statistically significant results.

Table 1: Characteristics of included studies.

Discussion and Conclusion

In our review, MMR vaccination and atopic diseases were assessed both by parental and medical reporting as well as objective clinical markers (serum IgE and selecting) [17-18]. Parental recall is likely to be incomplete, particularly for non-specific illness, such as fever or respiratory infections; this could imply ascertainment bias in cases and controls. The sample size was large enough in all studies. In spite of that, cases and controls groups were unbalanced in some studies [13-19]. Consequently, these studies may be prone to selection bias. Besides, we included studies with high power and multiple linear regressions were used to adjust confounding. In effect, variability of results between studies has proven that the interactions between MMR vaccination and atopic diseases are still unclear. Based on this, there is a need of large randomized controlled trials to find the consensus. Even so, the consensus could not be found. According to our analysis, several factors could influence the interactions between MMR vaccination and atopic diseases.

The relationship between some genes and atopic diseases is well known. A study has demonstrated the genes for IL-4, IL-13, HLA- DRB, TNF, LTA, FCER1B, IL-4RA, ADAM33, TCR a/5, PHF11, GPRA, TIM, p40, CD14, DPP10, T-bet, GATA-3, and FOXP3 are associated to atopic diseases [20]. Moreover, the child develops atopic dermatitis in the first months of life accompanied by sensitization to cow's milk, egg, or peanut, and sometimes also vomiting, diarrhea, or anaphylaxis in relation to ingestion of these foods beginning around the age of 6-12 months [1]. This is followed by sensitization to indoor allergens such as house dust mite, cockroach, and furred pets [1]. Thus, we hypothesize, considering only MMR vaccination and atopic diseases could not be fruitful in understanding different mechanisms. In this context, the concepts: Gene-environment- MMR vaccination and atopic diseases could be effective to clarify divergences between studies. Knowing that the studies were conducted in different community genetics, environments and lifestyle; the association between MMR vaccination and allergic asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis could not be established.

References

- Thomsen Simon F (2015) Epidemiology and natural history of atopic diseases. European Clinical Respiratory Journal 2(10): 3402.

- Moreno MA (2016) Atopic diseases in children 170(1): 96.

- Ninan TK, Russell G (1992) Respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren: evidence from two surveys 25 years apart. BMJ 304: 873-875.

- Zar HJ, Ehrlich RI, Workman L, Weinberg EG (2007) The changing prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema in African adolescents from 1995 to 2002. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 18(7): 560565.

- Nutten S (2015) Atopic Dermatitis: Global Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Ann Nutr Metab 66: 8-16.

- Roost HP, Gassner M, Grize L, Wuthrich B (2004) Influence of MMR- vaccinations and diseases on atopic sensitization and allergic symptoms in Swiss schoolchildren. Pediatric allergy and immunology: official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 15(5): 401-407.

- Fiset Pierre Olivier, Leung Donald YM, Hamid Qutayba (2006) Immunopathology of atopic dermatitis 118(1): 287-290.

- Kapsenberg Martien L (2003) Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. 3(12): 984.

- Timmermann CA, Osuna CE, Steuerwald U, Weihe P, Poulsen LK, et al. (2015) Asthma and allergy in children with and without prior measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination. Pediatric allergy and immunology: official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 26(8): 742-749.

- Ovsyannikova Inna G, Reid Karlene C, Jacobson Robert M, Oberg Ann L, Klee George G, et al. (2003) Cytokine production patterns and antibody response to measles vaccine 21(25-26): 3946-3953.

- Pabst Henry F, Spady Donald W, Carson Mary M, Stelfox H Tom, Beeler Judy A, et al. (1997) Kinetics of immunologic responses after primary MMR vaccination 15(1): 10-4.

- Jagelaviciene Agne, Usonis Vytautas (2014) Relationship between vaccination and atopy 21(3): 116-122.

- Bernsen RM, Van der Wouden JC (2008) Measles, mumps and rubella infections and atopic disorders in MMR-unvaccinated and MMR- vaccinated children. Pediatric allergy and immunology: official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 19(6): 544-551.

- Nagel Gabriele, Weinmayr Gudrun, Flohr Carsten, Kleiner Andrea, Strachan David P (2012) Association of pertussis and measles infections and immunizations with asthma and allergic sensitization in ISAAC Phase Two 23(8): 736-745.

- Olesen Anne Braae, Juul Svend (2003) Atopic dermatitis is increased following vaccination for measles, mumps and rubella or measles infection 83(6): 445-450.

- Rosenlund Helen, Bergstrom Anna, Alm Johan S, Swartz Jackie, Scheynius Annika, et al. (2009) Allergic disease and atopic sensitization in children in relation to measles vaccination and measles infection 123(3): 771778.

- Clara Amalie Gade Timmermanna , Esben Budtz-J0rgensen, Tina Kold Jensen, Christa Elyse Osunac (2017) Association between perfluoroalkyl substance exposure and asthma and allergicdisease in children as modified by MMR vaccination. Journal of Immunotoxicology 14(1): 3949.

- Hennino A, Cornu C, Rozieres A, Augey F, Villard Truc F, et al. (2007) Influence of measles vaccination on the progression of atopic dermatitis in infants. Pediatric allergy and immunology: official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 18(5): 385-90.

- Hviid Anders, Melbye Mads (2008) Measles mumps rubella vaccination and asthma-like disease in early childhood. 168(11): 1277-1283.

- Grammatikos Alexandros P (2008) The genetic and environmental basis of atopic diseases. Annals of Medicine 40(7): 482-495.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...