Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1644

Mini Review(ISSN: 2641-1644)

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Reproductive Risks and Choices Volume 1 - Issue 4

Myat San Yi1*, Khin Than Yee2 and Mon Mon Yee3

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia

- 2Department of Paraclinical Science, UNIMAS, Malaysia

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Newcastle University, Malaysia

Received: August 20, 2018; Published: August 27, 2018

Corresponding author: Myat San Yi, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), 94300 Kota Samarahan Sarawak, Malaysia

DOI: 10.32474/OAJRSD.2018.01.000117

Abbreviations: UV: Ultra-Violet; ANA: Antinuclear Antibodies; ss: Single-Stranded; Sm: Anti-Smith; CNS: Central Nervous System; ACR: American College of Rheumatology; CBC: Complete Blood Count; UKMEC: UK Medical Eligible criteria for Contraceptive use

Introduction

In ancient times, lupus means a disease that eats away, bites and destroys the skin and various organs. The Lupus Foundation of America estimates that 1.5 million Americans, and at least five million people worldwide, have a form of lupus. [1] There are four types of lupus accepted and they are Systemic lupus, cutaneous lupus, drug-induced lupus (mainly by drugs like hydralazine, Isoniazid.) and neonatal lupus. Systemic lupus accounts for approximately 70 percent of all cases of lupus [2]. It is a well-known autoimmune disease. It occurs predominantly in females in a varied ratio of 5 to10:1 according to previous studies. The course of the disease is a chronic, relapsing and remitting in nature. Its popularity among the autoimmune disease is its occurrence in reproductive aged women with multisystem involvement affecting the woman’s reproductive life as well as its potential fatality. The aetiology is still uncertain yet but is generally accepted that the damage is caused by the production of antibodies to react to own body tissues resulting in inflammation with the immune complex deposition and vasculopathy. There will be genetic or familial, ethnicity, socio-economic status, hormonal factors especially estrogen, and immunological factors involved. Environmental factors like certain viruses and ultra-violet (UV) light contribute in its aetiology. It is commoner in Asians and African-Americans.

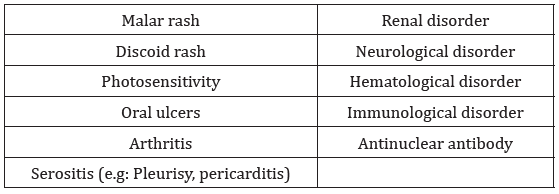

Many antibodies are detected like ANA (antinuclear Antibodiestarget nuclear components of Cells and important diagnostic marker); anti-double-stranded (ds) DNA antibodies, singlestranded (ss) DNA, anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies and the anti-Smith (Sm) antibodies resulting in organ damage. Other antiphospholipid antibodies like prothrombin activator complex, lupus anticoagulant as well as anti-cardiolipin antibodies can lead to abnormal clotting as well as loss of pregnancy. The prevalence of SLE varies around the world but in United States, it is around 20-150 cases per 100,000 population [3], reported estimated prevalence rates in women range from 35/100 000 in a white subpopulation in the UK [4]. The clinical features are generally malaise, fever, arthritis, rash and weight loss. The presenting symptoms may be complex and non-specific; therefore, it will be difficult to differentiate from other conditions like irritable bowel disease, HIV infection and other varieties of connective tissue diseases [5]. The presentation will be attributed to the organs involved. The symptoms will depend on the degree of severity and type of the organs damaged. In general, the skin, musculoskeletal system, and pulmonary system are primarily affected. Then, SLE also affects the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, renal, and hematological systems, as well as the central nervous system (CNS). Basically, the diagnosis is individualized and begins with a high index of suspicion. The ACR [6] (American College of Rheumatology) has 11 diagnostic criteria for SLE; if a patient meets at least four, SLE can be diagnosed with 95% specificity and 85% sensitivity. According to Lupus organisation, the diagnosis is based on the lupus check list provided to the patient to fill in with the presenting symptoms under the Rheumatologist care [7]. It is flanked with the appropriate diagnostic tests like ANA test (Table 1).

Four of these criteria are required simultaneously or serially.

The ACR recommends ANA testing in patients who have two or more unexplained signs or symptoms although it is not a specific test for SLE. It can be raised in other connective tissue diseases like Sjogren’s syndrome, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. When ANA titres are measured, laboratories should report ANA levels at both 1:40 and 1:160 dilutions and should supply information on the percentage of normal persons who are positive at each dilution [8]. Anti-dsDNA and anti-Smith (Sm) are two specific autoantibodies that are highly diagnostic for SLE. Other helpful blood tests like a complete blood count (CBC) and a urinalysis to determine the creatinine clearance and the presence of proteinuria or active sediment should be done. The testing of complement levels (C3 and C4) as potential markers during SLE flares is also useful. Radiography can be used to assess joint involvement; renal ultrasound, kidney size and impairment; chest radiography, pulmonary involvement; and electrocardiography, chest pain

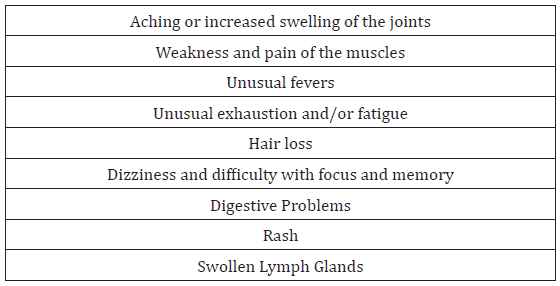

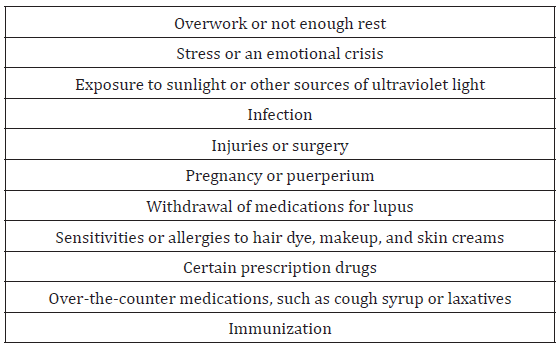

Complications can include kidney damage, including kidney failure, cognitive and memory impairment, neuropsychiatric symptoms, blood disorders and cardiovascular disease [4]. With the progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis and early recognition of the clinical symptoms, as well as the improvement in the diagnostic facilities and advanced medication result in longer survival rates and better quality of life. Apart from that, as it occurs commonly in reproductive aged women, the reproductive outcome is more worsened in those affected compared to general population. There are reproductive outcome failures like an increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, stillbirths, foetal growth restriction, preeclampsia and preterm delivery. There is an increased risk of SLE flare at any stage of the pregnancy or postpartum. Neither the severity nor type of the flare is altered by pregnancy [9]. The flares will be varied depending on the triggering factors, period of gestations and underlying immunological status with medication [10]. However, flare is difficult to diagnose in pregnancy as fatigue, erythema, anaemia and hair fall are common to both. [11] Risk of flare appears elevated during the second trimester, third trimester and puerperium. In particular, renal and hematologic flares may be more frequent, while musculoskeletal flares are decreased [4]. (Table 2,3)

A review of women treated at the Hopkins Lupus Pregnancy Center from 1987 to 1996 found that hypertension, preeclampsia, hyperglycemia, gestational diabetes, and bladder infections were more frequent in pregnant women with lupus [4]. There are evidences of thromboembolism in the affected women with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. These incidents strongly indicate the affected woman and her doctor to make a correct choice in the contraceptive methods to avoid unnecessary consequences. Unintended pregnancies, whether they are mistimed or unwanted, are especially problematic for women with SLE. Pre-eclampsia once developed makes difficult to differentiate from lupus nephritis. Both attribute to the signs and symptoms like low platelets, renal impairments, edema, hypertension and proteinuria. The only difference between these two pathologies are lupus nephritis has red cell casts in the urine with hypocomplementaemia and rising anti-DNA titre. On the other hand, pre-eclampsia includes raised transaminase and hyperuricemia [9]. Adverse pregnancy outcome is related to the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, renal involvement, disease activity and the presence of anti- Ro and anti-La antibodies. In addition, the drugs used in the treatment of SLE are not free from side effects like teratogenicity. According to Rebecca et al (2017), it is estimated that 5.8% of all pregnancies in U.S are exposed to category D or X medications. An estimated half of all pregnancies are unplanned in this study too [12]. To avoid the adverse reproductive outcome mentioned above, effective contraception is crucial for those affected with SLE.

Management

Pre-pregnancy counselling are essential to enable an accurate risk assessment and facilitate the pregnancy process. They are encouraged to conceive at the remission period. The management of SLE depends on the system involved. All patients with SLE should receive education, counselling, and support. Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) is the cornerstone of treatment because it reduces disease flares and other constitutional symptoms. It is safe in pregnancy but due to long half-life, the exposure to the foetus continues until three months once mother stopped using it. Once pregnancy has confirmed, NSAID needs to be stopped. Low-dose glucocorticoids can be used to treat most manifestations. Azathioprine is safe to use in pregnancy. Evidence from retrospective and cohort studies supports a role for low-dose aspirin. Recurrent pregnancy loss is possible in some groups of women and they should be screened for antiphospholipid antibodies [13].

Regarding the current contraceptive methods, no contraceptive method is ideal; all have benefits and drawbacks. The risk of use of a given contraceptive must be balanced against the known significant risks of pregnancy. The definitive guideline by UKMEC (UK medical eligible criteria for contraceptive use) in these groups is beneficial. According to UKMEC, copper IUD is the best choice (category 1- which indicates there is no restriction of the method), on the other hand, levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system is category 2 restrictions on the use of the method (Category 2 indicates the benefits generally outweigh the risks). There were concerns that oestrogen will increase the disease activity and thromboembolism. So many studies were conducted before to consider the association between the combined contraceptive pills and SLE. The evidence was the combined pills (including the oestrogen) may worsen the disease activity although one RCT study from Mexico not proved this [3], but UKMEC indicates Category 4 for combined pills. (Category 4 indicates an unacceptable health risk if the method is used by women with the medical condition). Progesterone containing pills, injectables and implanon are category 2.

Facilitating women’s access to a family planning specialist is very important to achieve the favorable outcome and prevent the unintended pregnancy and its related reproductive risks. Multidisciplinary approach with input from rheumatologist, hematologist, nephrologist, endocrinologist depending on the system involved in the disease process is beneficial to the management of these unfortunate women.

References

- GfK Roper (2012) Lupus Awareness Survey for the Lupus Foundation of America [Executive Summary Report]. Washington, DC.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, Scofield L, Reinlib L, Cooper GS (2010) Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Feb 39(4): 257- 268.

- Culwell KR, Curtis KM (2013) Contraception for women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 39: 9-11.

- Tesher (2010) contraception for adolescents with lupus, Pediatric Rheumatology 8: 10.

- Maidhof W, Hilas O (2012) Lupus: An Overview of the Disease And Management Options, P&T April 37(4): 240-246.

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines (1999) Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum 42(9): 1785-1796.

- Lupus checklist (https://resources.lupus.org/entry/diagnosing-lupus).

- Gill MJ, Quisel MA, Rocca VP, Walters TD (2003) Diagnosis of systemic Lupus Erythematosus. American Family Physician. December 68(11): 2179-2187.

- David M Luesley, Mark D Kilby (2010) Obstetrics and Gynaecology: an evidence-based text for MRCOG (2nd edn.): p. 92-98. Autoimmune disease by Catherine Nelsen Piercy.

- https://lupusrebel.com/lupus-flare

- https://www.webmd.com/lupus/preventing-lupus-flare#1

- Sadun RE, Wells MA, Balevic SJ, Victoria L, Erica JA, et al. (2017) Increasing contraception use among women receiving teratogenic medications in a rheumatology clinic. BMJ Open Quality 7(3).

- Vulam CN (2016) Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Primary Care Approach to Diagnosis and Management; American Family Physician 94(4).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...