Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1644

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1644)

Genito Urinary Syndrome of Menopause “A New Terminology for an Ever-Present Symptomatology” Volume 1 - Issue 5

Belardo Alejandra, Pilnik Susana, Gelin Marina* and Garcia Paola

- Department of Gynecology, Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, Argentina, South America

Received: October 22, 2018; Published: October 26, 2018

Corresponding author: Gelin Marina, Department of Gynecology, Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, Argentina, South America.

DOI: 10.32474/OAJRSD.2018.01.000125

Abstract

The genitourinary syndrome is a chronic and progressive entity characterized by symptoms such as vaginal irritation, burning, dryness, dyspareunia, dysuria and urinary urgency that affect the quality of life of most postmenopausal women. The aim of this article will be to review the terminology and the latest studies and recommendations regarding diagnosis, characteristics of the medical approach, observation of physical signs, relay of symptoms and implications for quality of life and therapeutic alternatives.

Keywords: Woman; Post menopause; Genitourinary Syndrome; Therapeutic Strategies

Introduction

During the climacteric period, the decrease in estrogen production by the ovaries results in various changes in different organs and systems of the body. Estrogen deficiency is translated into disturbances in metabolism, sleep and mood; vasomotor symptoms (VMS) such as hot flashes and sweating, as well as changes in skin elasticity and bone mineral density among others. The Vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA), resulting from the loss of estrogenic stimulation, is characterized by the thinning of the epithelial lining of the vagina and lower genitourinary tract, the loss of vaginal elasticity, vaginal dryness and an increase of vaginal pH [1]. Although this is a frequent, progressive and chronic entity, it continues to be underdiagnosed, little talked about and therefore undertreated in medical consultations, resulting many times in severe conditions that could have been avoided with an earlier diagnosis and approach [2]. Throughout this article the following points will be reviewed: the main characteristics of the GSM, its impact on the daily life of postmenopausal women (PM), its approach in the medical consultation and the main therapeutic options.

Genitourinary Syndrome

The purpose of replacing the classic VVA with GSM is to use a more pleasant, socially and medically acceptable term which includes several associated symptoms in both the sexual and urinary sphere, thus not being reductionist to only the vulvovaginal epithelium. The frequency, intensity and severity depend on the duration of menopause. After the first year since the last menstruation, changes in the vulvovaginal mucosa are mild and only 4% of women have clinical manifestations related to this condition. Throughout the years, estrogen levels start to diminish, and the symptoms related to the atrophy of the vaginal mucosa, vulva and genitourinary tract intensify. Consequently, 7 to 10 years later these can be observed in at least 50% of women and later on the prevalence reaches 75% of women [3]. It is a chronic and progressive entity [4]. It is characterized by a complex set of symptoms that can vary according to the individual characteristics of each woman, age, climacteric time, frequency of sexual relations and other factors. The loss of the estrogen stimulation of the vulvovaginal epithelium can translate into vaginal dryness, burning, irritation, lack of lubrication, dyspareunia, dysuria, and urinary urgency that may affect daily activities, sexuality, relationships, and the quality of life [5,6]. Estrogens play a major role in the anatomy and physiology of the vagina. After puberty and before menopause, the presence of endogenous estrogens is responsible for thick, resistant and well-vascularized vaginal walls.

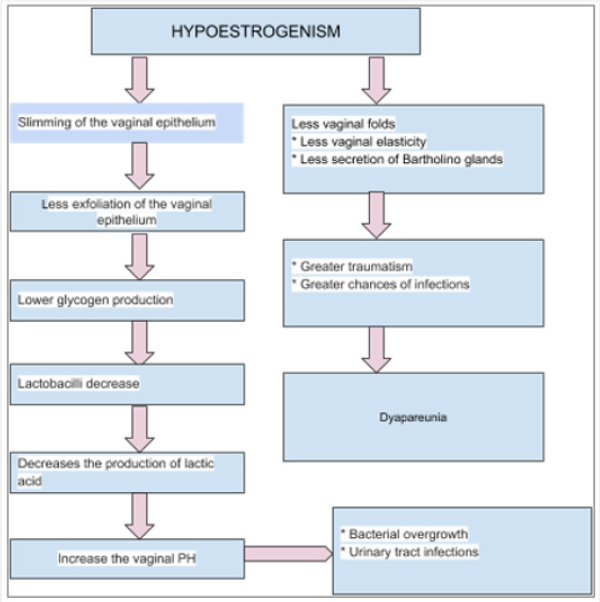

There are two types of estrogen receptors: α and β. The α receptor is present at all ages whilst the β receptor appear not to be expressed in PM women. The decrease in circulating estrogen levels modifies the genital area too. A pale, thin, dry and fragile vulvar epithelium can be observed, as well as, a narrower and shortened vagina and a reduced in size introitus (mainly in the absence of intercourse). These changes manifest clinically with dryness, pruritus, urinary urgency, overactive bladder, incontinence, dyspareunia and irritation [7]. Due to the decrease in lactobacilli, an increase in vaginal pH is observed, which goes from 3.5 - 4.5 to 6 or even 7.5; thus, losing an important barrier of protection against pathogens [8,9]. With time, the vagina becomes less elastic, thinner, loses rugae and can have a reduced vascular irrigation and less secretion from the sebaceous glands surrounding it, which can translate into less lubrication during sexual intercourse (Figure 1) [3,10]. Many studies have shown that the GSM is a frequent and prevalent issue that is rarely talked about by women and their doctors.

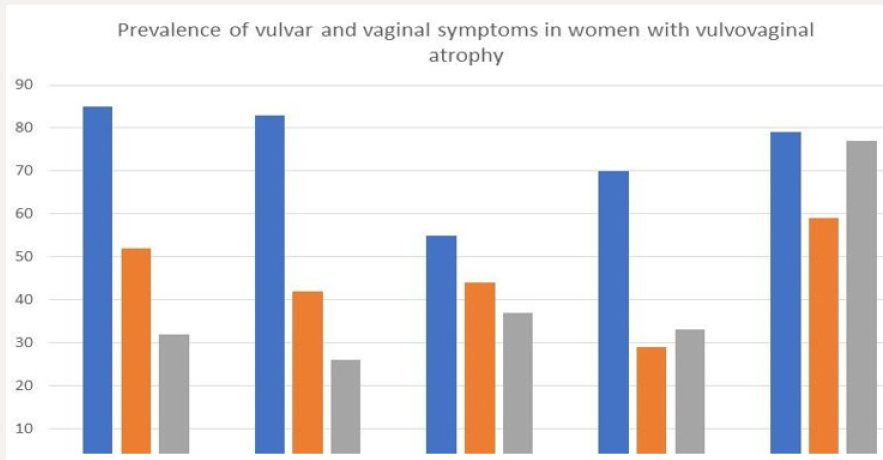

In recent years, several studies have shown similar findings when it comes to the GSM. The most frequently reported symptoms by women are [11-13]:

a) Vaginal dryness (75%).

b) Dyspareunia (40%).

c) Vulvo-vaginal itching.

d) Irritation.

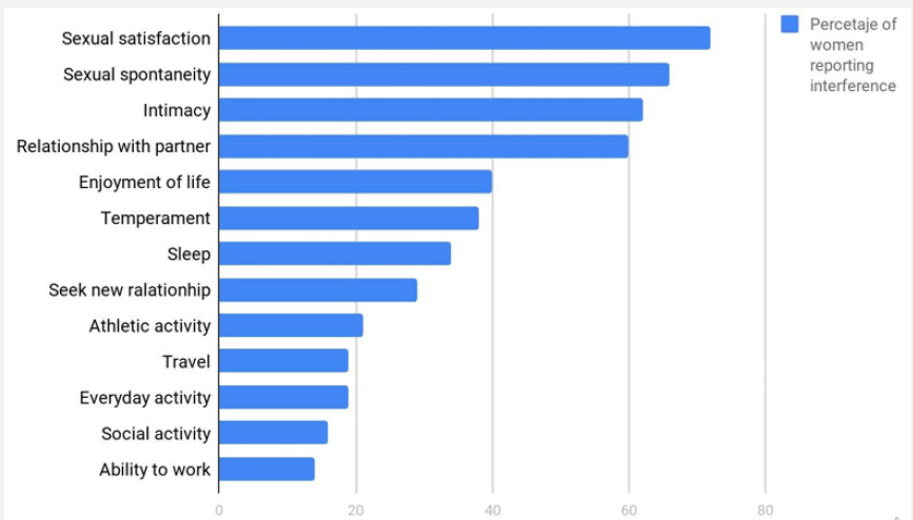

Generally, the first symptom to appear during the menopausal transition is vaginal irritation; whilst dryness and pain appear after the first year since the last menstruation [12,14-17]. In these studies, approximately 40% of the women associated their vulvo-vaginal symptoms with the climacteric (Figure 2) [18]. The discrepancy between high prevalence and underdiagnosis, added to the fact that it is a chronic and progressive entity, leads to a negative impact on the quality of life of women [14]. Over the years, the symptoms become more frequent and intense. In the study “THE AGATA” it was observed that 65% of PM women reported symptoms of VVA during the first year of menopause and 85% at six years [19]. Recent studies have shown that the decrease of quality of life in women aged between 40 to 75 years, with moderate to severe symptoms of the GSM, is comparable to that related to other chronic conditions such as arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and irritable bowel syndrome [20]. The impact of the symptoms most commonly associated with the GSM, according to the study REVIVE (Real Women´s Views of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal Changes), which included a cohort of 3758 PM women from Germany, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom, was high and mainly related to the sexual sphere: mainly regarding satisfaction, spontaneity in the search for sexual intercourse and intimacy with the partner (Figure 3) [17].

The VIVA study (Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes) inquired about the interference in the quality of life of many North American women. The results yielded the following [15]:

a) 87% felt that the symptoms negatively affect their quality of life.

b) 75% reported interference in their sexual life.

c) 58% reported that feeling “less sexual”.

d) 33% reported interference in their life with a partner

e) 26% reported worse self-esteem than in the past.

f) 25% considered that there was a decrease in their life quality.

Similar results were obtained by the American REVIVE study, which included 3046 PM women with symptoms associated with the GSM and showed that [16]:

a) 85% of women reported loss of intimacy.

b) 59% reported that it negatively influenced their ability to enjoy sex.

c) 47% of women with a partner reported that it interferes in their relationships.

d) 29% of women reported sleep disturbances.

e) 27% reported a decrease in their quality of life.

In general, between 52% to 80% of women reported that symptoms related to the GSM have a negative impact on their quality of life.

What happens in the medical consultation?

The American REVIVE study showed that only 7% of PM women were inquired by their doctor about symptomatology related to the GSM [16]. A very important fact regarding this topic is that most women feel that the symptoms related to the GSM are still taboo, even during the medical consultation. The recent EMPOWER study [18] evaluated PM women with symptoms of the GSM. It inquired about attitude and behavior related to the search for treatment. It compared the results with those of other studies: REVEAL [21], WVM [2], VIVA INT [14]and US [15], CLOSER [22] and REVIVE US and EU [17]. This showed that:

a) Less than half of the women with symptoms discussed the issue with their doctors.

b) Only 10%-15% of health professionals initiated a dialogue with their patients about vaginal symptoms.

c) 31-60% of women would have preferred that their doctor had initiated the conversation and would like to know more about this topic.

d) 64% of women would have appreciated to receive written material.

e) 41% would have liked to complete a questionnaire about the GSM.

Although it is a little talked about subject in the medical consultation, most of the women of this cohort reported that they would have felt comfortable talking to their doctor about vaginal discomfort.

The reasons given as to why the subject is not discussed frequently were:

a) Women consider them as symptoms expected to come with age [14-16]. The lack of knowledge about the therapeutic options [21].

b) That the symptoms were not bothersome enough to raise them.

c) The resistance of the health professionals to initiate the dialogue about the subject.

Treatment

The options will differ according to the country in which the health care professional is in. Generally, the following products are included:

a) Non-hormonal strategies.

b) Lubricants.

c) Vaginal moisturizers.

d) Local hormonal strategies.

The main objective of the treatment is to alleviate the symptoms.

Regarding this topic, recently, there have been discussions between different research groups in relation to the effects of the treatment on the GSM. This article will also deal with the latest evidence on the therapeutic options and the contrasts that arise from results obtained by different studies. The local administration of estrogen should be understood as a non-systemic tool which improves the symptomatology as it stimulates changes in the local urogenital tract conditions: vaginal pH, thickness, elasticity, urethral mobility, etc. In PM women with vaginal dryness, pruritus, pain or burning most meta-analysis of randomized studies conclude that local estrogen treatment in cream preparations reduces symptoms in most women. However, in general, the adherence is low, the cost is high and most abandon the treatment before 6 months [23]. The focus of the latest Cochrane review was on investigating the efficacy and safety of hormonal intravaginal preparations used for the treatment of the GSM. It included 30 randomized studies (6235 women) that compared different hormonal intravaginal preparations with each other or against placebo for at least 12 weeks.

The review concluded that the evidence was moderate to low quality, and the results showed that:

a) There was no difference between the use of estradiol ring compared to estradiol in cream or in capsule; but there was improvement when compared with placebo.

b) There was no difference in the improvement with the use of estrogen in cream and tablets.

c) There was no difference in the endometrial thickness between the use of creams and tablets.

d) There were no differences between the use of estrogen cream and gel isoflavones.

e) There were no differences in the rest of the body between the use of preparations with estrogen and placebo.

f) There was an increase in endometrial thickness in women who used cream compared to those who used a ring. Probably due to a higher dose of use in the cream.

g) There was improvement with the use of estrogen gel vs placebo.

The authors concluded that there is no difference in efficacy between the different local hormonal preparations, but that there is an improvement in the symptoms compared with placebo (low quality evidence) [24]. In 2013, the NAMS (North American Menopause Society), conducted an investigation and drafted a document that said that all estrogen preparations (vaginal ring, tablets and creams) are equally effective and tolerated for the management of symptoms related to the GSM. The choice should depend on the products available and the preference of the woman. It also describes that non-hormonal preparations, such as lubricants and creams, can alleviate symptoms in many women [25]. The UK guide NICE (The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) of 2015, recommends the use of estrogens in the treatment of the GSM, as does NAMS, without choosing one preparation over another [26]. The IMS (International Menopause Society) in its recommendations of 2016 indicates that urogenital symptoms should be treated with local estrogens from the beginning, leaving concomitant treatment with lubricants and moisturizer for those women who continue with symptoms despite the local estrogen use [27].

In general, the vast majority of studies that compared different types of estrogenic preparations with each other, did not find differences between them and described an improvement of vulvavaginal symptoms against placebo. However, in March of this year, the journal “JAMA Internal Medicine” published a study that brought a lot of controversy. It was 12 weeks, multicentric, randomized study in which 302 women aged between 50 to 70 years with moderate to severe symptoms related to the GSM participated. They were divided into 3 groups of treatment: 1) tablets of 10 micrograms of estradiol + placebo gel, 2) placebo tablet + vaginal lubricant and 3) placebo tablet + placebo gel. They observed a decrease in symptomatology in the three treatment groups, without a prevalence of estrogen over placebo. These results are striking and different from those showed by most studies and guides from different societies and countries [23].

In response to this study, the NAMS issued a statement entitled “It is not time to abandon the use of local hormonal treatments” and described that probably the subjective benefit in the use of placebo is due to the use of the gel. According to NAMS, the use of vaginal lubricants and moisturizers represent a good first line treatment of the GSM, but based on numerous studies of much longer duration, local hormonal treatment still remains an excellent therapeutic option for the GSM [28].

The included options

Lubricants and vaginal moisturizers

They are the first line of treatment as they can improve the vaginal pH and reduce friction and irritation during sexual intercourse. They can be applied on the vulva, in the vagina or on the penis [29-31]. The lubricants can be based on water, oil or silicone. There are few studies that demonstrate their safety regarding longterm toxicity, the relationship with the vaginal flora or the use of parabens. Oil-based products should not be used whilst using condoms. They provide relief of short-term symptomatology. There is evidence in the literature that oil-based lubricants may increase the risk of candidiasis and bacterial vulvovaginitis [32-34]. Vaginal moisturizers have a more lasting effect in relieving symptoms by improving the hydration of the vaginal mucosa and by decreasing its pH. They are administered regularly: daily or every 2-3 days, depending on the severity of the symptoms. It is important to use products with osmolarity and pH similar to that of normal vaginal discharge [35].

Vaginal Estrogens

They are preferred over systemic hormonal treatment. Its use in low doses provides many local benefits with poor systemic absorption. The local treatment proved to be more effective than the systemic one in the treatment of symptoms related to GSM: in several studies an 80-90% improvement was evidenced vs a 70% [36,37]. The benefit of estrogen was shown by numerous studies and reaffirmed by international guidelines as well as the Cochrane reviews. It has been shown that it rapidly improves the rate of cell maturation, increases vaginal thickness, decreases the pH and attenuates or eliminates the symptoms [38-41]. Concerning systemic absorption, it is considered that although it exists, it is low and insignificant. Most studies do not show an increase in endometrial thickness or an increased risk of hyperplasia or endometrial cancer [42-44]. Therefore, concomitant use with progesterone is not indicated [25,27,45]. The duration of the treatment should be individualized for each particular case. The existing preparations will depend on each country in particular. There are creams, vaginal rings, capsules and tablets; and its components may be estriol, estradiol, promestriene, conjugated equine estrogens or estrone. The use of local estrogens in women with a history of breast cancer is a topic still being discussed. The symptoms related to the GSM are frequent and severe in many women who are treated with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. Each case will be approached in particular but treatment with local moisturizers, lubricants or estrogens should be considered in these patients [1].

Serm (Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators)

Ospemifene: It is the first line non-hormonal oral treatment for the GSM. It is a SERM with agonist action at the level of the vaginal epithelium. It has been approved for an oral dose of 60 mg. since 2013 by the FDA (The US Food and Drug Administration) for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness [46,47]. It is metabolized mainly in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes, it is excreted by bile and is mainly eliminated with faeces. No increase in endometrial thickness has been observed in long-term studies [48,49]. Because it is a SERM, it should be avoided in women with a history or high risk of thrombosis [50]. The results of several studies show comparable results with the use of local estrogens in terms of pH, thickness and vaginal and urinary symptomatology [51].

Lasofoxifene: It is not yet approved by the FDA. It binds to both estrogen receptors. It has shown benefits in the vaginal epithelium in studies against placebo [52,53].

Bazedoxifene (BZD): It is used in combination with conjugated equine estrogens. It has shown a beneficial effect on bone mass, VMS and lipid profile, as well as breast and endometrial safety [54]. In combination with EEC (EEC 0.45 mg / BZD 20 mg) it was recently approved in Europe and the USA as a treatment for VMS in women with a uterus, and its main use is in women who cannot tolerate progesterone [55].

Tamoxifen, Raloxifene: With respect to Tamoxifen, its effect on the epithelium is not well established, although it apparently has an antiestrogenic effect. Raloxifene has not shown improvement in symptoms related to the GSM [56].

Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

It is a prohormone steroid that is metabolized vaginally into estrogen and testosterone.

It was approved by the FDA in November 2016 as a treatment for moderate to severe dyspareunia related to menopause AVV. It is administered intravaginally, daily, in doses of 0.50% (6.5 mg). Its efficacy was established in 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, 12- week studies that included 406 healthy PM women between 40 and 80 years of age with symptoms related to the GSM [57]. The effect seems to be strictly local and no systemic adverse effects have been observed. Several studies showed changes that included: decrease in parabasal cells, increase in superficial cells and decrease in vaginal pH; coinciding with the decrease in dyspareunia and vaginal dryness [58-60]. A recent study compared the use of vaginal DHEA (6.5 mg/d), conjugated equine estrogens (0.3 mg 2 times / week), estradiol (10 microgram / d for 2 weeks and then 2 times per week) and placebo in women with symptoms of the GSM. After 10 weeks there was a similar improvement in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in the groups that received treatment in contrast to the one that received placebo [61].

Laser

The use of fractionated CO2 laser has demonstrated effectiveness and satisfaction in the users. It is proposed as a novel non-hormonal alternative. It improves the vascularization and the thickness of the vaginal mucosa, stimulates the synthesis of new collagen and connective tissue, allows to restore the mucosal balance and therefore improves the symptoms of atrophy caused by the lack of estrogen [62-65]. It is worth clarifying that most of the studies are short (12 weeks) and do not count with randomization; control against placebo or are blind. Although it is a promising and interesting field of research, there still is a lack of serious studies that demonstrate its effectiveness and long-term consequences [66]. It is not approved by the FDA for this use, at this moment, the “VELVET” study (Randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy) is being carried out, which is a multicentric, randomized, prospective and simple blind study that compares the use of CO2 laser to vaginal creams with conjugated equine estrogens in the GSM treatment. It started in 2016 and its completion is expected for December of this year [67].

Conclusion

The GSM is a prevalent clinical entity, with a chronic and progressive course that interferes with different aspects of women’s lives. It is still an underdiagnosed and undertreated entity that causes increasing symptomatology and consequences in the medium and long term, which could be avoided with an early approach. As health professionals, it is worth taking a few minutes to consider why it is so difficult to include in the gynecological consultation questions related to GSM symptoms, that is, the sexual and urinary changes and impact in the quality of life. According to the majority of scientific studies and the recommendations of large societies, it is the health care professionals who should initiate the discussion and ask the woman directly if she has any difficulty, doubt or question about this topic as well as perform to a gynecological examination aimed at observing signs of the GSM. Through these, the intent is to try to overcome prejudice and help eliminate the stigma around the subject. There are many therapeutic alternatives, therefore the patient should be informed about the different options and the treatment should be chosen according to their preferences and needs. Small gestures and medical interventions will be responsible for large changes in the well-being of those women who experience the GSM.

References

- Portman DJ, Gass ML (2014) Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 21(10): 1063-1068.

- Nappi RE, Kokot Kierpa M (2010) Women´s voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas 67(3): 233-238.

- Naumova I, Castelo Branco C (2018) Current treatment options for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. International Journal of Women’s Health 10: 387-395.

- Nappi R, Particco M, Biglia N, Cagnacci A, Di Carlo C, et al. (2016) Attitudes and perceptions towards vulvar and vaginal atrophy in Italian post-menopausal women: Evidence from the European Revive survey. Maturitas 91: 74-80.

- Lachowsky M, Nappi RE (2009) The effects of oestrogen on urogenital health. Maturitas 63(2): 149-151.

- Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT (2010) Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc 85(1): 87-94.

- Roberts H, Hickey M (2016) Managing the menopause: An update. Maturitas 86: 53-58.

- Caillouette JC, Sharp CF, Zimmerman GJ, Subir R (1997) Vaginal pH as a marker for bacterial pathogens and menopausal status. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 176(6): 1270-1275.

- Crandall C (2002) Vaginal estrogen preparations: A review of safety and efficacy for vaginal atrophy. International Journal of Women’s Health 11(10): 857-877.

- Bachmann GA, Cheng RJ, Rovner E (2007) Vulvovaginal complaints. In: Lobo RA ed. Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects, 3rd edn. Burlington, MA: Academic Press 263-270.

- Minkin MJ, Reiter S, Maamari R (2015) Prevalence of postmenopausal symptoms in North America and Europe. Menopause 22(11): 1231- 1238.

- Kigsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S (2017) The Women´s EMPOWER survey: identifying women´s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) and treatment. J Sex Med 14(3): 413-424.

- Santoro N, Komi J (2009) Prevalece and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med 6(8): 2133-2142.

- Nappi RE, Kokot Kierepa M (2012) Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes (VIVA)-results from an international survey. Climacteric 15(1): 36-44.

- Simon JA, Kokot Kierepa M, Goldstein J (2013) Vaginal health in the United States: results from the Vaginal Health: Insights Views and Attitudes survey. Menopause 20(10): 1043-1048.

- Kigsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L (2013) Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (Real Women´s Views of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vavinal Changes) survey. J Sex Med 10(7): 1790-1799.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S, Panay N (2016) Vulvar and vaginal atrophy on four European countries: evidence from the European REVIVE survey. Climacteric 19(2): 188-197.

- Krychman M, Graham S, Bernick B, Mirkin S, Kingsberg SA (2017) The Women´s EMPOWER Survey: Women´s Knowledge and Awarness of Treatment Options for Vulvar and Vaginal Atrophy Remains Inadequate. J Sex Med 14(3): 425-433.

- Palma F, Volpe A, Villa P (2016) Vaginal atrophy of women in postmenopause. Results from a multicentric observational study: The AGATA study. Maturitas 83: 40-44.

- Di Bonaventura M, Luo X, Moffat M, Kumar M, Bobula J, et al. (2015) The association between volvavaginal atrophy symptoms and quality of life among postmenopausal women in the United States and western Europe. J. Womens Health 24(9): 713-722.

- Krychman M, Kingsberg S (2009) REVEAL: Revealing Vaginal Effects at Mild-Life: surveys of postmenopausal women and health care professionals who treat postmenopausal women, Wyeth.

- Nappi RE, Mattson LA, Lachowsky M (2013) The CLOSER survey: impact of postmenopausal discomfort on relationships bethween women and their partners in Northern and Southern Europe. Maturitas 75(4): 373- 379.

- Mitchell C, Reed S, Diem S, Newton KM, Caan B, et al. (2018) Efficacy of Vaginal Estradiol or Vaginal Moisteurizer vs Placebo for treating Postmenopuasal vovla vaginal Symptoms A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 178(5): 681-690.

- Lethaby A, Ayeleke RO, Roberts H (2016) Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8: CD001500.

- (2013) Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 20(9): 888-902.

- (2015) Menopause: diagnosis and management. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE Guideline NG23.

- Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A (2016) 2016 IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric 19(12):109-150.

- Pinkerton JV (2018) Not Time to Abandon Use of Local Vaginal Hormone Therapies. Menopause 25(8): 855-858.

- Lee YK, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, et al. (2011) Vaginal pHbalanced gel for the control of atrophic vaginitis among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 117(4): 922- 927.

- Bygdeman M, Swahn ML (1996) Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 23(3): 259-263.

- Nachtigall LE (1994) Comparative study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril 61(1): 178-180.

- Sandhu RS, Wong TH, Kling CA, Chohan KR (2014) In vitro effects of coital lubricants and synthetic and natural oils on sperm motility. Fertil Steril 101(4): 941-944.

- Voeller B, Coulson A, Bernstein G, Nakamura R (1989) Mineral oil lubricants cause of rapid deterioration of latex condoms. Contraception 39(1): 95-102.

- Brown JM, Hess KL, Brown S, Murphy C, Waldman, et al. (2013) Intravaginal practices and risk of bacterial vaginosis and candidiasis infection among a cohort of women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 121(4): 773-780.

- Edwards D, Panay N (2016) Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric 19(2): 151-161.

- Long CY, Liu CM, Hsu SC, Wu CH, Wang CL, et al. (2006) A randomized comparative study of the effects of oral and topical estrogen therapy on the vaginal vascularization and sexual function in hysterectomized postmenopausal women. Menopause 13(5): 737-743.

- Cardozo L, Bachmann G, McClish D, Fonda D, Birgerson L (1998) Metaanalysis of estrogen therapy in the management of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women: second report of the Hormones and Urogenital Therapy Committee. Obstet Gynecol 92(4 pt 2): 722-727.

- Palacios S (2009) Atrophy urogenital. Managing urogenital atrophy. Maturitas 63(4): 315-318

- Castelo Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, Nohales F, Juliá MD (2005) Management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas 52 Suppl1(1): 46-52

- Sturdee DW and Panay N (2010) International Menopause Society Writing Group. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 13(6): 509-522.

- Pickar JH (2013) Emerging therapies for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Maturitas 75(1): 3-6.

- Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV (2014) Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 124(6): 1147-1156

- Shifren JL (2018) Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology 61(3): 508-516.

- Ulrich LS, Naessen T, Elia D, Goldstein JA, Eugster Hausmann M (2010) Endometrial safety of ultra-low-dose Vagifem 10 microg in postmenopausal women with vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 13(3): 228- 237.

- Simon J, Nachtigall L, Gut R, Lang E, Archer DF, et al. (2008) Effective treatment of vaginal atrophy with an ultra-low-dose estradiol vaginal tablet. Obstet Gynecol 112: 1053-1060.

- Santen RJ, Pinkerton JV, Conaway M (2002) Treatment of urogenital atrophy with low-dose estradiol: preliminary results. Menopause 9(3): 179-187.

- Bondi C, Ferrero S, Scala C, Tafi E, Racca A, et al. (2016) Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and clinical efficacy of ospemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia and genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 12(10): 1233-1246.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO (2010) Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause 17(3): 480-486

- Simon JA, Lin VH, Radovich C, Bachmann GA (2012) One-year long-term safety extension study of ospemifene for the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with a uterus. Menopause 20(4): 418-427.

- Portman D, Palacios S, Nappi RE, Mueck AO (2014) Ospemifene, a nonoestrogen selective oestrogen receptor modulator for the treatment of vaginal dryness associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Maturitas 78(2): 91-98

- Constantine GD, Goldstein SR, Archer DF (2015) Endometrial safety of ospemifene: results of the phase 2/3 clinical development program. Menopause 22(1): 36-43.

- Mirkin S, Pickar JH (2015) Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): a review of clinical data. Maturitas 80(1): 52-57.

- Pinkerton JV, Stanczyk FZ (2014) Clinical effects of selective estrogen receptor modulators on vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause 21(3): 309-319.

- Mirkin S, Pickar JH (2015) Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): a review of clinical data. Maturitas 80(1): 52-57.

- Komm BS, Kharode YP, Bodine PV, Harris HA, Miller CP, et al. (2005) Bazedoxifene acetate: a selective estrogen receptor modulator with improved selectivity. Endocrinology 146(9): 3999-4008.

- Pinkerton JV, Komm BS, Mirkin S (2013) Tissue selective estrogen complex combinations with Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a model. Climacteric 16(6): 618-628.

- Komm BS, Mirkin S (2013) Evolution of the tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC). J Cell Physiol 228(7): 1423-1427.

- (2016) FDA approves Intrarosa for postmenopausal women experiencing pain during sex. FDA News Release. Noviembr de. En: Visitado.

- Labrie F, Archer DF, Koltun W, Vachon A (2016) VVA Prasterone Research Group. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause 23(3): 243-256.

- Archer DF, Labrie F, Bouchard C, Portman Dj (2015) Treatment of pain at sexual activity (dyspareunia) with intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone) Menopause 22(9): 950-963.

- Labrie F, Archer DF, Martel C, Vaillancourt M, Montesino M (2017) Combined data of intravaginal prasterone against vulvovaginal atrophy of menopause. Menopause 24(11): 1246-1256.

- Archer DF, Labrie F, Montesino M, Martel C (2017) Comparison of intravaginal 6.5mg (0.50%) prasterone, 0.3mg conjugated estrogens and 10μg estradiol on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 174: 1-8.

- Abrahamse H (2012) Regenerative medicine, stem cells, and low-level laser therapy: future directives. Photomed Laser Surg 30(12): 681-682.

- Salvatore S, Athanasiou S, Candiani M, Stefano S, Stavros A, et al. (2015) The use of pulsed CO2 lasers for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 27(6): 1-8.

- Hutchinson Colas J, Segal S (2015) Genitourinary syndrome of menopause therapy. Maturita 82(4): 342-345.

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Parma M, Chionna R (2015) Sexual function after fractional microablative CO2 laser in women with vulvovaginal atrophy. Climacteric 18(2): 219-225.

- Rabley A, OShea T, Terry R (2018) Laser Therapy for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. Curr Urol Rep 19(10): 83.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...