Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1644

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1644)

Effectiveness of Textile Materials in Gynaecology and Obstetrics Volume 1 - Issue 1

Gokarneshan N*

- Department of Textile Technology, Park College of Engineering and Technology, India

Received: January 27,2018; Published: February 16,2018

Corresponding author: N Gokarneshan, Department of Textile Technology, Park College of Engineering and Technology, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

DOI: 10.32474/OAJRSD.2018.01.000104

Abstract

The article reviews some significant advances in the use of textile materials in obstetrics and gynaecological procedures. Some developments in texture suture materials have been highlighted. Despite millennia of experience with wound closure biomaterials, no study or surgeon has yet identified the perfect suture for all situations. In recent years, a new class of suture material-barbed suture-has been introduced into the surgeon's armamentarium. Focus has been directed on barbed suture to better understand the role of this newer material in obstetrics and gynaecology. Cellulose nonwoven modified with chitosan nano particles has been developed and its physical-chemical, morphological and physical-mechanical aspects characterized in order to explore their possible use in medicine as gynaecological tampons. Tampons have been developed using viscose fibres coated by chitosan dissolve in acetic or lactic acids both inhibit the growth of micro organisms and adjust the pH. Such a tampon proved better than existing ones and thereby proves beneficial for pregnant women.

Keywords: Suture material; Suture characteristics; Barbed sutures; Medical tampons; Viscose; Chitosan; Wound closure

Introduction

The relationship between wound closure biomaterials and surgery dates back as far as 4000 years, when linen was used as a suture material. The list of materials used to close wounds has included wires of gold, silver, iron, and steel; dried gut; silk; animal hair; tree bark and other plant fibers; and, more recently, a wide selection of synthetic compositions. Despite millennia of experience with wound closure biomaterials, no study or surgeon has yet identified the perfect suture for all situations. Natural polymers like cellulose, starch and chitosan find use in pharmacy and medicine due to their desired properties like biocompatibility, lack of toxicity and allergenic action [1,2]. Prepared from natural polymers are materials that mimic the extracellular matrix; they reveal a soft and strong but also elastic structure which provides mechanical stability to tissue and organs [3,4].

The availability and low price is the economic assets of natural polymers. Environment protection issues, now strongly pronounced by the European Union, also speak for the use of natural polymers, which are seen as environmentally-friendly. In general, natural polymers enjoy a growing interest. They are primarily used in modern medical devices contributing to advanced healing procedures. Chitosan counts as a polymer and is in abundance in nature, revealing beneficial biomedical properties like antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, which is primarily responsible for septic shock [5-7]. During the recent years, cellulosic fibres have been used in the development of medical textile products as proved by the literature available [8,9]. Owing to their active surface area, strength and molecular structure, cellulosic fibres exhibit enormous possibilities in the design of bioactive, biocompatible, and advanced materials [10]. One such area of application could be cellulose tampons which are used by women and have biodegradable and antimicrobial properties. It protects from physiological and pathological vaginal discharge, which could otherwise increase the vaginal pH beyond the desirable limit of 3.6-4.5 [11].

Developments in Suture Materials

A perfect suture would have the following properties:

a. Adequate strength for the time and forces needed for the wounded tissue to heal

b. Minimal tissue reactivity

c. Comfortable handling characteristics

d. Unfavourable for bacterial growth and easily sterilized

e. Nonelectrolytic, noncapillary, nonallergenic, and noncarcinogenic

This review discusses the wound healing process and the biomechanical properties of currently available suture materials to better understand how to choose suture material in obstetrics and gynaecology. Inflammatory tissue reactions due to the presence of suture material will persist as long as the foreign body remains within the tissue. Determining the balance between the added strength the suture provides to the tissues while they heal versus the negative effects of inflammation is central to choosing the proper suture. Irrespective of the knot configuration and material, the weakest spot in a surgical suture is the knot and the second weakest point is the portion immediately adjacent to the knot, with reductions in tensile strength reported from 35% to 95% depending on the study and suture material used. Applying our current understanding of the wound healing process and the biomechanical properties of the variety of available suture materials, obstetricians and gynaecologists should choose suture material based on scientific principles rather than anecdote and tradition.

Stages in Wound Healing

The following stages are involved in wound healing and inflammatory responses

A. Inflammation [12-16]

B. Proliferation [17]

C. Maturation an remodelling [12,13]

Suture Characteristics that Assist Surgeons

The following are the different categories of suture classification that are considered to best assist surgeons in choosing the proper suture material for their surgeries. These are:

i. Suture size [18].

ii. Tensile strength [19-21].

iii. Absorbable versus nonabsorbable [22-27].

iv. Multifilament versus monofilament [28-31]

v. Stiffness and flexibility [32,33].

vi. Smooth versus barbed [34-42].

vii. Barbed suture [43].

Practical Aspects to be considered in Suture Materials

A perfect suture has adequate strength for the time and forces needed for the wounded tissue to heal; minimal tissue reactivity; comfortable handling characteristics; is unfavourable to bacterial growth and easily sterilized; and is nonelectrolytic, noncapillary, nonallergenic, and noncarcinogenic.

a) Inflammatory tissue reactions due to the presence of suture material persist as long as the foreign body remains within the tissue. The degree of tissue reaction depends largely on the chemical nature and physical characteristics of the suture material.

b) Suture classifications that best assist surgeons in choosing the proper suture material for surgery include suture size, tensile strength, absorbability, structure, flexibility, and surface texture.

c) The perfect suture material should retain adequate strength throughout the healing process and disappear afterward with minimal associated inflammatory reaction.

d) Irrespective of the knot configuration and material, the weakest spot in a surgical suture is the knot and the second weakest point is the portion immediately adjacent to the knot, with reductions in tensile strength reported from 35% to 95% depending on the study and suture material used.

e) Bidirectional barbed sutures may offer multiple advantages: they eliminate the need for a knot, which effectively reduces wound tissue reactions; there is a more uniform distribution of wound tension across the suture line, yielding more consistent wound opposition; and the secure anchoring of barbed suture at 1 mm intervals may provide a reduction in gaps and thereby create a more "watertight" seal. On the downside, currently available barbed sutures are produced in a limited variety of materials and sizes.

Reflecting the age-old dictum, "It's always important to never say always and never," there is no one best suture or suture material for all surgical procedures. Although sutures have been reflecting the age-old dictum, "It's always important to never say always and never," there is no one best suture or suture material for all surgical procedures. Although sutures have been complications, surgeons must constantly review not only their technique, but the adjuvant materials they use in their craft. This review focused on absorbable suture materials for use in basic obstetric and gynaecologic procedures. It is meant to be neither comprehensive nor definitive. Rather, it is intended to introduce newer technologies and reinforce old concepts. Applying our current understanding of the wound healing process and the biomechanical properties of the variety of available suture materials, obstetricians and gynaecologists should choose suture material based on scientific principles rather than anecdote and tradition. Tissue characteristics, tensile strength, reactivity, absorption rates, and handling properties should be taken into account when selecting a wound closure suture. The currently available suture materials and their relative general characteristics have been listed [44].

With these considerations in mind, in most obstetric and gynaecologic procedures (excluding suspension procedures and oncologic procedures in which either adjuvant chemotherapy and/ or radiation therapy is anticipated), there is little role for either nonabsorbable sutures or collagen gut sutures [45]. The newer synthetic absorbable sutures consistently display both theoretical and clinically proven advantages for wound healing over their older, naturally derived cousins. The introduction of bidirectional barbed sutures has the potential to dramatically alter the wound closure landscape by both equalizing the distribution of disruptive forces across the suture line and eliminating the need for surgical knots.

Use of Barbed Sutures

Sutures and surgery have been tied together since the first operations were performed. Throughout the history of surgery, the variety of materials used to close wounds has included wires of gold, silver, iron, and steel; dried gut; silk; animal hairs; tree bark and other plant fibers; and, more recently, a wide selection of synthetic compositions. Despite the multitude of different procedures performed with a host of different wound closure biomaterials, no study or surgeon has yet identified the perfect suture for all situations. In recent years, a new class of suture material-barbed suture-has been introduced into the surgeon's armamentarium. Currently, there are 2 commercially available barbed suture products: the Quill™ SRS bidirectional barbed suture product line (Angiotech Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) and the V-Loc™ Absorbable Wound Closure Device product line (Covidien, Mansfield, MA). These synthetic sutures eschew the traditional, smooth, knot requiring characteristic of sutures in favour of barbs that serve to anchor the sutures to tissue without knots. This review focuses specifically on barbed suture to better understand the role of this newer material in obstetrics and gynaecology. Given the paucity of published data on the V-Loc sutures, the review will mostly focus on Quill bidirectional barbed sutures.

Key Considerations

In the author's opinion, there are few scientific data to support the current use of either plain or chromic gut sutures in any surgical procedure. A recent study of porcine gastrointestinal closure burst- strength pressures in wounds closed with barbed suture were no different than repairs performed with traditional knotted, smooth suture lines. When considerations for blood loss and hemostatis are added, the need for faster, more secure suture lines becomes readily apparent. To this end, barbed suture materials are an ideal solution. As with myomectomy closures, hysterotomy closures during caesarean delivery are facilitated by the use of barbed suture. The barbed sutures more easily draw the tissue edges together and the 1-mm spacing between the barbs seems to yield better hemostasis.

Important Practical Aspects

I. A new class of suture material-barbed suture-has been introduced; these synthetic sutures eschew the traditional, smooth, knot requiring characteristic of sutures in favour of barbs that serve to anchor the sutures to tissue without knots.

II. The 6 categories of suture classification believed to best assist surgeons in choosing the proper suture material for their surgeries are suture size, tensile strength, absorbability, filament construction, stiffness and flexibility, and surface characteristics (smooth or barbed).

III. A knot-secured, smooth suture creates an uneven distribution of tension across the wound. Although the closed appearance of a wound may be that of equal tension distribution, there is unequal tension burdens placed on the knots. This tension gradient across the wound may subtly interfere with uniform healing and remodelling.

IV. Although the data are limited and almost exclusively based on studies with bidirectional suture, barbed suture lines appear to be at least as strong if not stronger than traditional, knotted, smooth suture lines.

V. To choose the best suture material for an obstetrics- gynaecology procedure, surgeons should take into account all the variables present, such as a tissue's collagen structure, blood supply, disruptive forces, and potential for infection. When these characteristics are considered, the physical characteristics of barbed sutures make these materials an attractive option.

Comparison between Smooth and Barbed Sutures

In 1956, Dr. J. H. Alcamo was granted the first.com patent for a unidirectional barbed suture, although the concept dates back to 1951 when the idea of using barbed sutures was presented for tendon repairs [46,47]. The first.com Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for barbed suture material was issued in 2004 to Quill Medical, Inc., for its Quill bidirectional barbed polydioxanone suture [48]. In March 2009, the FDA approved the V-Loc 180 barbed suture from Covidien. Whether bidirectional or unidirectional barbed suture is better is unknown, although there are reported complications of unidirectional barbed sutures migrating or extruding [49,50].

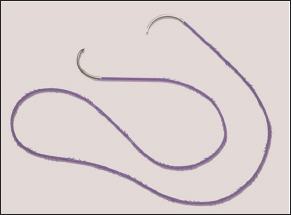

This problem is thought to have been due to the lack of counterbalancing forces on the suture line. Barbed sutures are available in a variety of both absorbable and nonabsorbable monofilament materials. Specifically, currently available bidirectional and unidirectional barbed suture materials include PDO, polyglyconate, poliglecaprone 25, glycomer 631, nylon, and polypropylene. Bidirectional barbed sutures are manufactured from monofilament fibers via a micromachining technique that cuts barbs into the suture around the circumference in a helical pattern. The barbs are separated from one another by a distance of 0.88 to 0.98 mm and are divided into 2 groups that face each other in opposing directions from the suture midpoint (Figure 1) [51].

Figure 1:

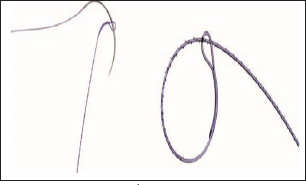

Needles are swaged onto both ends of the suture length. Owing to its decreased effective diameter as a result of the process of creating barbs, barbed suture is typically rated equivalent to 1 USP suture size greater than its conventional equivalent. For example, a 2-0 barbed suture equals a 3-0 smooth suture. Unidirectional barbed sutures are similarly manufactured from monofilament fibers, but needles are swaged onto only 1 end whereas the other end maintains a welded closed loop to facilitate initial suture anchoring (Figure 2). Unlike bidirectional barbed suture, unidirectional barbed suture is rated equal in strength to its USP smooth suture counterpart. However, this strength rating difference between the 2 barbed varieties is the result of labeling differences rather than an actual material benefit.

Figure 2:

Importance of suture knots

It is difficult for many surgeons to think about suture material without an accompanying knot. Nonetheless, the surgical knot used with a length of smooth sutures is a significant necessary evil that is accepted as the only irrefutable means to anchor suture material within a wound. A knot-secured, smooth suture inevitably creates an uneven distribution of tension across the wound. Although the closed appearance of a wound may be that of equal tension distribution, there is unequal tension burdens placed on the knots rather than on the length of the suture line. This tension gradient across the wound may subtly interfere with uniform healing and remodelling. The weakest spot in any surgical suture line is the knot. The second weakest point is the portion immediately adjacent to the knot, with reductions in tensile strength reported from 35% to 95% depending on the study and suture material used [52,53].

When functional biomechanics are considered, this finding should not be surprising considering both the effects of slippage of suture material through the knot and the unavoidable suture elongation that occurs as a knot is formed and tightened. Given the excessive relative wound tension on the knot and the innate concerns for suture failure due to knot slippage, there is a predilection toward overcoming these concerns with excessively tight knots. However, surgical knots, when tied too tightly, can cause localized tissue necrosis, reduced fibroblast proliferation, and excessive tissue overlap, all of which lead to reduced strength in the healed wound [54]. A surgical knot represents the highest amount and density of foreign body material in any given suture line. The volume of a knot is directly related to the total amount of surrounding inflammatory reaction [55]. If minimizing the inflammatory reaction in a wound is important for optimized wound healing, then minimizing knot sizes or eliminating knots altogether should be beneficial as long as the tensile strength of the suture line is not compromised. Finally, with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgeries, the ability to quickly and properly tie surgical knots has presented a new challenge. In cases where knot tying is difficult, the use of knotless, barbed suture can securely re-approximate tissues with less time, cost, and aggravation [56,57].

Although the skills necessary to properly perform intra- or extracorporeal knot tying for laparoscopic surgery can be achieved with practice and patience, this task is a difficult skill that most surgeons still need to master to properly perform closed procedures. In addition, laparoscopic knot tying is more mentally and physically stressful on surgeons and, more importantly, laparoscopically tied knots are often weaker than those tied by hand or robotically [58-62].

Barbed Sutures in Practical Use

The choice and use of sutures in obstetrics and gynaecology (ob- gyn) is based more on anecdote and experience than data. Though many of the suture materials routinely used in myomectomies, hysterectomies, and caesarean deliveries have endured the test of time, this should preclude neither the application of scientific review nor the quest for improvement. In addition to understanding the physical properties and characteristics of the variety of available sutures, surgeons need to consider the tissue and physiologic milieu into which suture will be placed before choosing the material to use. For example, in general, the suture-holding strength of most soft tissues depends on the amount of fibrous tissue they contain. Thus, skin and fascia hold sutures well whereas brain and spinal cord tissue do not. Further along this line, healthier tissues tend to support sutures better than inflamed, edematous tissues.

To choose the best suture material for an ob-gyn procedure, surgeons should take into account all the variables present, such as a tissue's collagen structure, blood supply, disruptive forces, and potential for infection. When these characteristics are considered, the physical characteristics of barbed sutures make these materials an attractive option. The first use of barbed sutures in gynaecologic surgery was reported by Greenberg and Einarsson in 2008 [56]. Since that report, numerous print and video publications have followed. Inprocedures such as laparoscopic myomectomy and hysterectomy, the use of barbed sutures has become commonplace. Myomectomy re-approximation of the myometrium after removal of myomas requires a suture material that adequately addresses the need for a prolonged wound disruptive-force reduction, hemostasis, and minimal tissue reactivity.

Traditionally, this suture has been either a polyglycolic acid suture or polydioxanone. However, as noted earlier, braided sutures cause more tissue abrasion and inflammation than monofilaments, and the transition from open to closed procedures has introduced the difficulty of laparoscopic suturing. When considerations for blood loss and hemostatis are added, the need for faster, more secure suture lines becomes readily apparent. To this end, barbed suture materials are an ideal solution. Their synthetic, monofilament configurations should minimize local inflammation, and their absorption profiles and tissue pull-through strengths are well within the parameters needed for reduction of disruptive forces. Further, because barbed sutures allow for only minimal tissue recoiling, closing spaces such as myomas defects is easier with each subsequent suture pass exposed to less tension than the previous bite. Finally, without the need for knot tying, wound closure times and blood loss are significantly reduced [63-65].

Barbed sutures are used in obstetric and gynaecologic procedures in following areas

a) Hysterectomy [66-71].

b) Sacrocolpopexy [72-74].

c) Caesarean delivery [75-79].

Barbed suture is a relatively new but exciting addition to the variety of suture materials. As experience grows with barbed sutures, more applications for its use will likely arise [80]. Obstetric and gynaecologic surgeons who are interested in choosing the best materials for their operations should benefit from better understanding the underlying principles of wound healing and suture material biomechanics, and may discover many advantages to the use of barbed suture.

Chitosan Modified Cellulosic Nonwoven Material

It also displays activity against the fungi Candidiaalbicans, which often produces vaginal candidiasis [81,82], and antiviral action, for example against the human papilloma virus (HPV), which is the cause of cervical carcinoma [83-85]. Thanks to its ability of controlled slow- release, chitosan is often used as carrier of active substances. Various sterilization methods can be employed for chitosan without upsetting its structure and physical-chemical properties [86]. Its beneficial properties ensure chitosan is widely used in pharmacy and medicine as a safe, non-toxic polymer originating from nature [86,87]. Both natural and synthetic polymers like PLA, poly (DL-lactideco-glycolide) and PP are often modified with chitosan [88-91]. The process is intended to prepare new materials with beneficial biological, physical-chemical and mechanical properties [91-93]. The modified composite materials obtained open wide avenues of application and contribute to the introduction of new healing techniques. The incorporation of chitosan into the cellulose matrix yields devices with high biological activity and good mechanical strength.

The medical devices have potential use in gynaecology as medical materials with beneficial biological and mechanical properties. Basic cellulose material with built-in chitosan nanoparticles provides optimal and controlled diffusion of chitosan to the mucous membrane of the vagina and ovarium. Tampons holding antimicrobial chitosan particles may also find use as post-operation dressings and in the healing of diseases and infections due to high antimicrobial activity; alternatively they may be employed for carrying active substances. This is crucial because infections and gynaecological ailments are problems women are mostly plagued with. More than 40 microorganisms are the reason for infections in the region of female sexual organs. The copolymer system proposed also permits to minimalise irritation due to the adjustment of chitosan concentration as the active agent. It is also hoped that the more developed surface of the biopolymer material shall provide better contact with the vagina and neck of the uterus, thus enhancing the antimicrobial effect. The use of modern biopolymer medical devices opens new ways in medicine.

Assessment of the impact of chitosan nanoparticles added to a cellulose matrix upon biological activity and toxicity was the aim of the research conducted. Structural examinations and estimation of chemical purity, as well as antibacterial and useful properties were made. Prepared was a system to control the medical device in respect of microorganism growth and fulfilment of quality requirements of medical devices [94,95]. This article presents preliminary studies on the assessment of the effect of modification of cellulose nonwoven with nanoparticles of chitosan upon biological activity, toxicology and mechanical properties. The addition of nano chitosan was supposed to influence antimicrobial properties; however it was necessary to verify the correlation between the concentration of chitosan and the activity. A very important purpose was to examine how the addition of chitosan would influence the mechanical properties and chemical purity. It is necessary to guarantee optimum activities and the safety of human life and health simultaneously. Therefore according to the standards and scientific literature available, research methods were selected and used to assess cellulose nonwovens for their possible use in medicine as gynaecological tampons. Cellulose fibres used in the preparation of the nonwovens have good properties, both physical- mechanical and physical chemical, including chemical purity.

The addition of chitosan in the amount of 0.25 and 0.5% to the nonwoven caused an inhibition of the growth of E. coli, while such an effect was not observed with S. Aureus. Nonwoven with a 1.4% content of chitosan completely stopped the growth of bacteria E. coli and S. Aureus. The initial material revealed antifungal activity against C. Albicans on at the level of 91.7%; the addition of 0.5% of chitosan entirely inhibited the growth of microorganisms. Antifungal activity of the nonwoven with 0.25% of chitosan against C. albicans was slightly below 100%. Based on the results of physical-mechanical testing, it was found that the nonwoven with 0.5% of chitosan has the best mechanical and useful properties [96]. Assessment of the chemical purity of the materials tested points, at best, to useful properties in the case of nonwoven with 0.5% of chitosan. The structure of the fibres examined after extraction simulating normal use was not disturbed, which may evidence safe use of the hygiene material manufactured. Summarizing the results of the examinations, it may be concluded that the initial cellulose fibres are a good raw material for use in the preparation of innovative medical devices.

Use of Chithsan Based Viscose Material

An increase in pH may cause a reduction in the natural defence of the vagina. This suggests conduciveness for development of bacteria and hence prone to development of bacteria [11-12,9798]. A number of techniques and formulations have been evolved in order to manage the problem of increased pH value of the vagina, than the normal [13,99]. But these have been unsatisfactory from the practical point of view considering the usage and acceptability. Therefore, the development of materials for prevention and treatment of gynaecological infections still represent a significant challenge. Chitosan is the next most abundant polysaccharide found on earth, in comparison with cellulose. It is a biopolymer that is polycationic and covers a broad spectrum of medical properties activity, such as antibacterial, antifungal, and haemostatic properties [100]. Chitosan possesses many desirable characteristics with regard to vaginal infections. It is effective against vaginal candidiasis, toxic shock syndrome, treatment of ovarian cancer, and ensures safe pregnancy and proves conducive in avoiding premature child birth.

Chitosan is found highly suitable for adsorption onto cellulose fibres and thereby impart antimicrobial activity. The functionalization of viscose cellulose using chitosan has been investigated. The objective is to assess the potential use of such a material for the development of new tampons, which apart from maintaining/creating the desired physiological pH value would also possess antibacterial and antimycotic properties. The tampons do not exhibit negative effects, such as inflammation risks, and infections from yeasts, and on repeated use, help to sustain the required moisture in the vagina.

Conclusion

Textile materials have made their entry into many areas of medical textiles, of which gynaecology and obstetrics is one such. Textile sutures are one well explored area. In the choice of a wound closure suture tissue characteristics, tensile strength, reactivity, absorption rates, and handling properties should be considered. The wound healing process and the biomechanical properties of currently available suture materials have been reviewed to better understand how to choose suture material in obstetrics and gynaecology. Despite the multitude of different procedures performed with a host of different wound closure biomaterials, no study or surgeon has yet identified the perfect suture for all situations. In recent years, a new class of suture material-barbed suture-has been introduced into the surgeon's armamentarium. The barbed suture has been studied to better understand the role of this newer material in obstetrics and gynaecology. The impact of the addition of chitosan nanoparticles upon the biological activity and toxicity of the materials prepared.

Methodology was prepared for the examination of the gynaecological devices in the range of their useful properties, notably the mechanical strength, surface density and absorption. Aqueous extracts were examined after an extraction process that simulated standard use of the medical device, and after a surplus extraction. The content of water-soluble-, surfactant- and reductive substances was estimated as well as the contents of heavy metals like cadmium, lead, zinc and mercury by the ASA method. Morphology examination permitted to assess the impact of the extraction processes on the fibre structure. Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, and antifungal activity against Candida albicans was measured. Altogether examinations were made to assess whether the cellulosic nonwoven modified with chitosan nanoparticles meets the demands of medical devices and lends itself to the manufacture of tampons. The suitability of chitosan-acetic acid treated tampons for gynaecological use has been evaluated. The use of such tampons could prove beneficial for pregnant women, as in vitro trials have confirmed resistance of the tampons against Streptococcus Agalactiae bacteria, which pose serious problems for pregnant women and their infants.

References

- Amidi M, Mastrobattista E, Jiskoot W, Hennink WE (2010) Chitosan- based delivery systems for protein therapeutics and antigens. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 62(1): 59-82.

- Friess WC (1998) Collagen- Biomaterial for drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 45(2): 113-136.

- Oledzka E, Sobczak M, Koiodziejski WL (2007) Polymers in medicine- review of recent studies. Polimery 52(11-12): 793-916.

- Stojadinovic A, Carlson JW, Schultz GS, Davis TA, El-ster EA (2008) Topical advances in wound care. Gynecol Oncol 111(2): 70-80.

- Niekraszewicz A, Lebioda J, Kucharska M, Wesoiowska E (2007) Research into Developing Antibacterial. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 1(60): 101-105.

- Brzoza MK, Kucharska M, Wisniewska WM, Guzinska K, Ulacha BA (2015) Modified Cellulose Products for Application in Hygiene and Dressing Materials Part I. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 3(111): 126-132.

- Brzoza MK, Kucharska M, Wisniewska WM, Kazmierczak D, Jozwicka J, et al. (2015) Modified Cellulosic Products for Application in Hygiene and Dressing Materials- Part II. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 5(113): 124-128.

- Edward JV, Buschle-Diller G, Goheen SC (2006) Modified fibres with medical and speciality applications. Springer, Berlin, USA.

- Ravi kumar MNV (2000) A review of chitin and chitosan applications. Reactive and Functional Polymers 46(1): 1-27.

- Bliss SJ, Manning SD, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Pearlman MD, et al. (2002) Group B Streptococcus colonization in male and non pregnant female university students: a cross sectional prevalence study. Clin Infect Dis 34(2): 184-190.

- Boskey ER, Telsch KM, Whaley KJ, Moench TR, Cone RA (1999) Acid production by vaginal flora in vitro is consistent with the rate and extent of vaginal acidification. Infect Immun 67(10): 5170-5175.

- Broughton G, Janis JE, Attinger CE (2006) Wound healing: an overview Plast Reconstrt Surg 117(7 suppl): 1e-S-32e-S.

- Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers M, Mattox KL (2007) Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 18th edn. The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice 51(7): 1154.

- Martin P (1997) Wound healing-aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 276(5309): 75-81.

- Gurtner G, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT (2008) Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 453: 314-321.

- Witte MB, Barbul A (2002) Role of nitric oxide in wound repair. Am J Surg 183(4): 406-412.

- Kivisaari J, Vihersaari T, Renvall S, Niinikoski J (1975) Energy metabolism of experimental wounds at various oxygen environments. Ann Surg 181(6): 823-828.

- (2009) Pharmacopoeia Web site, India.

- (2009) Covidien AG. Our Products Web site, USA.

- Ethicon (2009) Inc. Ethicon Product Catalog Sutures: Absorbable Website, USA.

- (2009) Angiotech Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Quill™ SRS Instructions for Use Web site, UK.

- Chu CC (1997) Classification and general characteristics of suture materials. (In Eds: Chu CC, von Fraunhofer JA, Greisler HP. Wound Closure Biomaterials and Devices. Boca Raton) FL: CRC Press, USA.

- Chu CC (1997) Chemical structure and manufacturing processes. (In Eds: Chu CC, von Fraunhofer JA, Greisler HP. Wound Closure Biomaterials and Devices. Boca Raton) FL: CRC Press, USA.

- Barham RE, Butz GW, Ansell JS (1978) Comparison of wound strength in normal, radiated and infected tissues closed with polyglycolic acid and chromic catgut sutures. Surg Gynecol Obstet 146(6): 901-907.

- Chu CC (1997) Chemical structure and manufacturing processes. (In Eds: Chu CC, von Fraunhofer JA,Greisler HP. Wound Closure Biomaterials and Devices. Boca Raton) FL: CRC Press, USA, p. 69-76.

- (2003) Data on file. Somerville, Ethicon Inc, New jersey, USA.

- Kowalsky MS, Dellenbaugh SG, Erlichman DB, Gardner TR, Levine WN, et al. (2008) Evaluation of suture abrasion against rotator cuff tendon and proximal humours bone. Arthroscopy 24(3): 329-334.

- Trimbos JB, Brohim R, van Rijssel EJ (1989) Factors relating to the volume of surgical knots. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 30(4): 355-359.

- Molokova OA, Kecherukov AI, AlievFSh, et al. (2007) Tissue reactions to modern suturing material in colorectal surgery. Bull Exp Biol Med 143(6): 767-770.

- Bucknall TE (1983) Factors influencing wound complications: a clinical and experimental study. Ann R CollSurg Engl 65(2): 71-77.

- von Fraunhofer JA, Chu CC (1997) Mechanical properties. In Chu CC, von Fraunhofer JA, Greisler H (Eds.), Wound Closure Biomaterials and Devices. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press, USA, p. 11.

- Chu CC, Kizil Z (1989) Quantitative evaluation of stiffness of commercial suture materials. Surg Gynecol Obstet 168(3): 233-238.

- Tera H, Aberg C (1976) Tensile strengths of twelve types of knot employed in surgery, using different suture materials. Acta Chir Scand 142(1): 1-7.

- Tera H, Aberg C (1977) Strength of knots in surgery in relation to type of knot, type of suture material and dimension of suture thread. Acta Chir Scand 143(2): 75-83.

- Kim JC, Lee YK, Lim BS, Rhee SH, Yang HC (2007) Comparison of tensile and knot security properties of surgical sutures. J Mater Sci Mater Med 18(12): 2363-2369.

- Stone IK, von Fraunhofer JA, Masterson BJ (1986) The biomechanical effects of tight suture closure upon fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet 163(5): 448-452.

- van Rijssel EJ, Brand R, Admiraal C (1989) Tissue reaction and surgical knots: the effect of suture size, knot configuration, and knot volume. Obstet Gynecol 74(1): 64-68.

- Berguer R, Smith WD, Chung YH (2001) Performing laparoscopic surgery is significantly more stressful for the surgeon than open surgery. Surg Endosc 15(10): 1204-1207.

- Berguer R, Chen J, Smith WD (2003) A comparison of the physical effort required for laparoscopic and open surgical techniques. Arch Surg 138(9): 967-970.

- Kadirkamanathan SS, Shelton JC, Hepworth CC, Hepworth CC, Laufer JG, et al. (1996) A comparison of the strength of knots tied by hand and at laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg 182(1): 46-54.

- Lopez PJ, Veness J, Wojcik A, Curry J (2006) How reliable is intracorporeal laparoscopic knot tying? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 16(4): 428432.

- Alcamo JH (1964) Inventor. Surgical suture. US patent 3.

- Chu CC (1997) Classification and general characteristics of suture materials. In: Chu CC, von Fraunhofer JA, Greisler HP (Eds.), Wound Closure Biomaterials and Devices. Boca Raton) FL: CRC Press, USA, p. 49.

- James A, Greenberg MD, Rachel MC (2009) Advances in Suture Material for Obstetric and Gynecologic Surgery. Reviews in obstetrics & gynaecology 2(3): 146-158.

- McKenzie AR (1967) An experimental multiple barbed suture for the long flexor tendons of the palm and fingers. Preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Br 49(3): 440-447.

- Quill™ Synthetic Absorbable Barbed Suture. 510(k) Summary.

- Villa MT, White LE, Alam M, Yoo SS, Walton RL (2008) Barbed sutures: a review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg 121(3): 102e-108e.

- Winkler E, Goldan O, Regev E, Mendes D, Orenstein A, et al. (2006) Stensen duct rupture (sialocele) and other complications of the Aptos thread technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 118(6): 1468-1471.

- Leung JC (2004) Barbed suture technology: recent advances. Presented at: Medical Textiles Pittsburgh, PA.

- Greenberg JA, Einarsson JI (2008) The use of bidirectional barbed suture in laparoscopic myomectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 15(5): 621-623.

- Moran ME, Marsh C, Perrotti M (2007) Bidirectional barbed sutured knotless running anastomosis v classic Van Velthoven suturing in a model system. J Endourol 21(10): 1175-1178.

- Chandra V, Nehra D, Parent R, Woo R, Reyes R, et al. (2010) A comparison of laparoscopic and robotic assisted suturing performance by experts and novices. Surgery 147(6): 830-839.

- O Reilly MP, Vakil JJ, Sutter E (2010) Biomechanical comparison of medial parapatel lararthrotomy repair. Presented at: 2010 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, USA.

- Högström H, Haglund U, Zederfeldt B (1990) Tension leads to increased neutrophil accumulation and decreased laparotomy wound strength. Surgery 107(2): 215-219.

- Bartlett LC (1985) Pressure necrosis is the primary cause of wound dehiscence. Can J Surg 28(1): 27-30.

- Einarsson JI (2010) Single-incision laparoscopic myomectomy myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17(3): 371-373.

- Alessandri F, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, Ferrero S (2010) Unidirectional barbed suture versus continuous suture with intracorporeal knots in laparoscopic myomectomy: a randomized study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17(6): 725-729.

- Einarsson JI, Vellinga T, Twijnstra ARH, Suzuki Y, Greenberg JA (2009) Use of bidirectional barbed suture in laparoscopic myomectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy: an evaluation of safety and clinical outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 16(6): S28-S29.

- Sowa DE, Masterson BJ, Nealon N, von Fraunhofer JA (1985) Effects of thermal knives on wound healing. Obstet Gynecol 66(3): 436-439.

- Hur HC, Guido RS, Mansuria SM, Hacker MR, Sanfilippo JS, et al. (2007) Incidence and patient characteristics of vaginal cuff dehiscence after different modes of hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 14(3): 311317.

- Manyonda IT, Welch CR, McWhinney NA, Ross LD (1990) The influence of suture material on vaginal vault granulations following abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 97(7): 608-612.

- Rivlin ME, Meeks GR, May WL (2010) Incidence of vaginal cuff dehiscence after open or laparoscopic hysterectomy: a case report. J Reprod Med 55(3-4): 171-174.

- Einarsson JI, Suzuki Y (2009) Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: 10 steps toward a successful procedure. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2(1): 57-64.

- Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, et al. (2004) Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol 104(4): 805-823.

- Visco AG, Advincula AP (2008) Robotic gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 112(6): 1369-1384.

- Ghomi A, Askari R (2010) Use of a bidirectional barbed suture in robot- assisted sacrocolpopexy. J Robot Surg 4(2): 87-89.

- Williams J (2011) Obstetrics. New York: D. Appleton and Company, USA.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KL, Bloom SL (2009) Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. (In: Cunningham F, Leveno K, Bloom S (Eds.), Williams Obstetrics, 23ri edn). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, USA.

- Dodd JM, Anderson ER, Gates S (2008) Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD004732.

- Sestanovic Z, Mimica M, Vulic M, et al. (2003) Does the suture mater and technique have an effect on healing of the uterotomy in cesarean section? LijecVjesn 125: 245-251.

- Murtha AP, Kaplan AL, Paglia MJ, Mills BB, Feldstein ML, et al. (2006) Evaluation of a novel technique for wound closure using a barbed suture. Plast Reconstr Surg 117(6): 1769-1780.

- James AG (2010) The Use of Barbed Sutures in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reviews in obstetrics & gynecology 3(3): 82-91.

- Seyfarth F, Schliemann S, Elsner P and Hipler UC (2008) Antifungal effect of high- and low molecular-weight chitosan hydrochloride, carboxymethyl chitosan, chitosan oligosaccharide and N-acetyl- dglucosamine against Candida albicans, Candida krusei and Candida glabrata. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 353(1-2): 139-148.

- Aksungur P, Sungur A, Unal S, Iskit AB, Squier CA, et al. (2004) Chitosan delivery systems for the treatment of oral mucositis: in vitro and in vivo studies. Journal of Controlled Release 98(2): 269-279.

- Tahamtan A, Ghaemi A, Gorji A, Kalhor HR, Sajadian A, et al. (2014) Antitumor effect of therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines with chitosan-based nanodelivery systems. Biomed Sci 21(1): 69.

- Tahamtan A, Tabarraei A, Moradi A, Dinarvand M, Kelishadi M, et al. (2015) Chitosan nanoparticles as a potential nonviral gene delivery for HPV-16 E7 into mammalian cells. Cells NanomedBiotechnol 43(6): 366372.

- Mucha M (2010) Chitosan-versatile polymer from renewable resources. Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne, Warszawa 7: 118-127.

- Niekraszewicz A, Kucharska M, Wawro D, Struszczyk MH, Kopias K (2007) Development of a Manufacturing Method for Surgical Meshes Modified by Chitosan. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 3(62): 105109.

- Struszczyk MH, Ratajska M, Brzoza MK (2007) Films and Non-wovens Coated by Chitosan for Special Applications: Biological Decomposition Aspect. Fibres andTextiles in Eastern Europe 2(61): 105-109.

- Niekraszewicz A, Kucharska M, Wisniewska WM, Kardas I (2010) Biological and Physicochemical Study of the Implantation of a Modified Polyester Vascular Prosthesis. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 6(83): 100-105.

- Kucharska M, Niekraszewicz A, Kardas I, Marcol W, Wiaszczuk A, et al. (2012) Developing a Model of Peripheral Nerve Graft Based on Natural Polymers. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 6B(96): 115-120.

- Niekraszewicz A, Kucharska M, Kardas I, Szadkowski M (2009) Resorbable Tightening of Blood Vessel Protheses Prepared from Synthetic Polymers. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 6(77): 93-98.

- Urreaga JM, de la Orden MU (2006) Chemical interactions and yellowing in chitosan-treated cellulose. European Polymer Journal 42(10): 26062616.

- Niekraszewicz A, Kucharska M, Struszczyk MH, Rogaczewska A, Struszczyk K (2008) Investigation into Biological Composite Surgical Meshes. Fibres and Textiles in Eastern Europe 6(71): 117-121.

- (2015) The United States Pharmacopeia USP 38 NF 33, USA.

- European Pharmacopoeia-(8th edn) Psychical and physicochemical methods 1( 2.2).

- (2009) ASTM: E2149-01. Standard Test Method for Determining the Antimicrobial Activity of Immobilized. Antimicrobial Agents Under Dynamic Contact Conditions - Shaking Flask C. Albicans, USA.

- Gzyra JK, JóŹwicka J, Gutowska A, Paiys B, Kazmierczak D (2016) Chitosan-Modified Cellulosic Nonwoven for Application in Gynecology. Impact of the Modification Upon Chemical Purity, Structure and Antibacterial Properties. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe 6(120): 210-217.

- Tomas MS, Bru E, Nader-Macias ME (2003) Comparison of the growth and hydrogen peroxide production by hydrogen peroxide by vaginal probiotic lactobacilli under different culture conditions. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 188(1): 35-44.

- Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, Albert X, Ng CW (2008) Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in post menopausal women. Cochrane database system review 16(2): CD005131.

- Erikkson K, Carlsson B, Forsum U, Larsson PG (2005) A double blind treatment study of bacterial vaginosis with normal vaginal lactobacilli after an open treatment with vaginal clindamycin ovules. ActaDermVenereol 85(1): 42-46.

- Chung YS, Lee KK, Kim JW (1998) Durable press and antimicrobial finishing of cotton fabrics with a citric acid and chitosan treatment. Text Res J 68: 722.

- Liu J, Wang Q, Wang A (2007) Synthesis and characterization of chitosan- g-poly (acrylic acid)/sodium humate superabsorbent. Carbohydrate Polymers 70(2): 166-173.

- Zitao Z, Cheng L, Jinmin J, Yanliu H, Donghui C (2003) Antibacterial properties of cotton fabrics treated with chitosan. Text Res J 73: 1103.

- Urreaga M, de la Orden MU (2006) Chemical interactions and yellowing in chitosan treated cellulose. Eur Polym J 42(10): 2606-2616.

- Yang Q, Dou F, Borun L, Shen Q (2005) Studies of cross linking reaction on chitosan fibre with glyoxal .Carbohydrate Polymers 59(2): 205-210.

- Calamari S, Bojanich A, Barembaum S, Azcurra A, Virga C, Dorronsoro S, et al. (2004) High molecular weight chitosan and sodium alginate effect on secretary acid proteinase of Candida albicans. Rev Iberoam Micol 21(4): 206-208.

- Yang TC, Chou CC, Li CF (2005) Antibacterial activity of N-alkylated disaccharide chitosan derivatives. Int J Food Microbiol 97(3): 237-245.

- Berrada M, Serreqi A, Dabbarh F, Owusu A, Gupta A, et al. (2005) A novel non toxic camptothecin formulation for cancer therapy. Biomaterials 26(14): 2115-2120.

- Hirnle L, Heimrath J, Woyton J, Klosek A, Hirnle G, et al. (2001) Application of 2% clindamycin cream in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis and valuation of methylcellulose gel containing the complex of chitosan F and PVP k-90 with lactic acid as carrier for intravaginallyadhbited medicines in the cases of pregnancies with the symptoms of preterm delivery. Ginekol Pol 72: 1096.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...