Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1644

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1644)

Challenges in the Treatment of Vasomotor Symptoms: Update in Non-Hormonal Strategies Volume 1 - Issue 3

Belardo Maria Alejandra1*, Pilnik Susana2, Cavanna Malena3, De Nardo, Barbara4, Starvaggi Agustina5 and Gelin Marina6

- 1Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina

- 2Department of Gynecological Endocrinology Climacteric Section, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina

- 3,4,5,6Department of Gynecology, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Received: July 20, 2018; Published: July 25, 2018

Corresponding author: Maria Alejandra, Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina

DOI: 10.32474/OAJRSD.2018.01.000113

Abstract

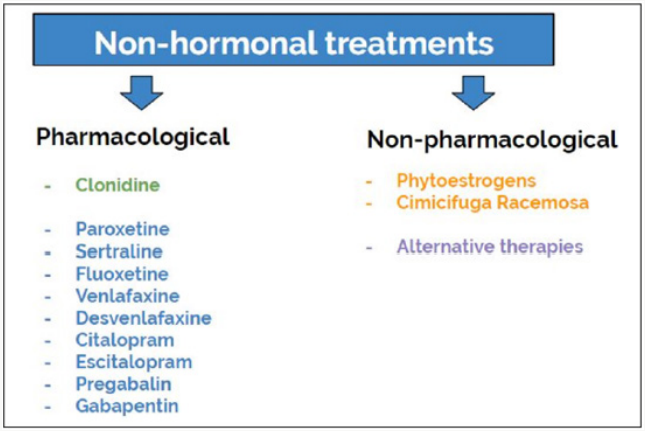

Perimenopause and menopause per se significantly impacts on women quality of life (QoL), especially due to vasomotor symptoms (VMS); their duration is uncertain, and often long. Although menopause hormone therapy (MHT) is the most effective treatment for climacteric symptoms as a whole, its use is contraindicated in some cases. Therefore, it is mandatory that different treatment approaches be offered to women for whom hormone therapy is contraindicated. As for treatment selection, there are a wide range of nonhormonal options, both pharmacological and nonpharmacological. These options include alternative or natural therapies (isoflavones and Cimicifuga Racemosa), lifestyle modifications and complementary therapies. Regarding pharmacological strategies the literature review shows that serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antihypertensives and anticonvulsants, decrease the intensity and frequency of VMS, proving a clinically significant improvement.

Keywords: Hot flashes; Vasomotor symptoms; Nonhormonal treatment; Alternative therapies; Isoflavone; Cimicifuga racemose; Breast cancer; Antidepressants; Antiepileptics

Abbreviations: VMS-Vasomotor Symptoms; QoL-Quality of Life; MHT-Menopause Hormone Therapy; SNRIs-SerotoninNorepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors; SSRIs-Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; FMP-Final Menstrual Period; CBT-CognitiveBehavioral Therapy; GABA-Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid; IMS-International Menopause Society; FDA-Food and Drug Administration; NAMS-North American Menopause Society

Introduction

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) affect approximately 75% of menopausal women, of which 25% report a negative impact on quality of life (QoL). Its duration and frequency vary from one woman to another and can often be prolonged for many years. Hot flashes are described as a feeling of intense heat, with face and neck flushing, accompanied by perspiration and tachycardia, often followed by chills. The SWAN study (an observational study of the menopause transition), enrolled 3302 women and had a 17-year follow up, showed an average total mean duration of 7.4 years and a mean persistence after the final menstrual period (FMP) of 4.5 years [1]. Other studies, including the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project [2], found a total duration of 5.2 years; and the Penn Ovarian Aging Study [3] showed a total duration of 8.8 to 10.2 years and a post-FMP duration of 4.6 years.

A special mention deserves the patients with personal history of breast cancer, since it has been reported that they experience a significantly greater amount of moderate to severe hot flashes due to the treatment of their underlying disease. Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors are usually part of the standard management in these patients after surgical treatment and may aggravate or induce hot flashes in these women [4] Although menopause hormone therapy (MHT) is the most effective treatment for climacteric symptoms, as a whole including hot flashes, in some cases, whether because hormonal treatment is contraindicated or due to the patient’s refusal to use it, non-hormonal treatments can be considered. Detecting habits and behaviors that pose a risk to health, which are fundamental pillars of the VMS’ treatment, such as lifestyle modifications, counseling on healthy habits and stopping harmful behaviors (e.g. providing smoking cessation counseling), should be part of the usual gynecological consultation [5]. Currently there are pharmacological approaches and nonpharmacological approaches (lifestyle modifications, complementary therapies and alternative therapies). On the one hand, nonhormonal treatments include the use of nonpharmacological alternatives and complementary therapies, such as acupuncture, relaxation techniques, Black Cohosh and ginseng, among others. On the other hand, pharmacological agents, include clonidine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), gabapentin and pregabalin. figure 1

Non-Pharmacological Strategies

Lifestyle Interventions and Complementary Therapies

There are few large randomized clinical trials that recommend lifestyle interventions and complementary therapies as first line treatment. However, good eating habits, as well as physical exercise and multiple relaxation techniques, are necessary in order to enjoy a good QoL. The level 1 recommendations (proven by high quality randomized clinical trials) include only cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and hypnosis [6]. Research conducted in the last decades consistently indicate that CBT is effective in the treatment of disorders such as depression or anxiety because it is based on the premise that one’s thoughts and behaviors play a major role in determining emotional responses. CBT consists in a structured psychological treatment of limited duration which has been widely investigated and has shown to be highly effective in reducing symptoms in a variety of health and mental health conditions, including major depression [7]. Two randomized controlled doubleblind clinical trials, menos 1 [8] (which compared women who have had breast cancer and were treated with CBT vs population without intervention) and menos 2 [9] (healthy women treated with CBT vs population without intervention), have shown a significant reduction in the intensity of VMS [6]. CBT positively impacts both the perception of VMS and stress control, improving patients’ QoL, quality of sleep and VMS [10].

Hypnosis is a psycho-physical therapy which uses a state of deep relaxation, mental images and customized suggestions [6]. Hypnosis is studied for a wide variety of pathologies, such as anxiety and chronic pain. In regard to VMS, two clinical trials were performed: one randomized patients with a personal history of breast cancer [11] and the other one included women with over seven hot flashes per day [12]. Both studies concluded that patients in the group that used hypnosis therapy had approximately a 70% reduction in the intensity of hot flashes. Recommendations with inconclusive or insufficient evidence include weight loss, physical exercise, mindfulness therapy, multiple relaxation techniques, yoga [13], acupuncture [14,15], cooling techniques, avoidance of triggers and stellate ganglion block.

Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived non-steroidal compounds with weak estrogenic action. The most studied group consists of isoflavones, mostly the soy-derived ones: genistein and daidzein, which exhibit a structure similar to estradiol. They may be taken through diet modifications o as dietary supplements. Many foods are a source of phytoestrogens, such as legumes, mainly soy (isoflavones), flaxseed (lignans), alfalfa and soybean sprouts (coumestans) [5]. Phytoestrogens are taken orally and are metabolized by the intestinal bacteria. This intestinal metabolism seems key for optimizing their action, and fundamental for treatment response. The ability to metabolize phytoestrogens varies by ethnicity: 30% in North American women [6] and a much higher percentage in Asian women. As for their mechanism of action, phytoestrogen bind to estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ), with a higher binding affinity to ERβ. It is believed that the biological function of isoflavones depends of endogenous levels of estradiol [6]. When endogenous estradiol levels are high, isoflavones have an anti-estrogenic action binding with ERα [6], but when levels are low (such as in post menopause), they have an estrogenic action by activating the ERβ.

As for hot flashes, isoflavones and derivatives are more effective than placebo [16] and should be prescribed to women with moderate to severe hot flashes [17]; however, a review by Cochrane in 2013 concluded that there is no consistent evidence to prove that phytoestrogen supplements effectively reduce the frequency or severity of VMS in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women [18]. There are controversial results regarding phytoestrogens and breast cancer. Prepuberal exposition of breast acini to phytoestrogens may cause them to mature early and, therefore, offer protection. In contrast, post pubertal exposition without breast maturity may potentially increase the risk of cancer through their estrogen agonist action. In turn, it was suggested that genistein appears to have a proliferative action on in vivo breast epithelium. Consequently, the use of isoflavones is currently not recommended in women with a history of breast cancer [19].

Cimicifuga Racemosa

Cimicifuga Racemosa (actaea racemosa, black cohosh, black bugbane, black snakeroot, fairy candle) is a perennial herb of the Ranunculaceae family, native of the USA and Canada. Cimicifuga extracts include triterpene glycoside and phenolic acids [6]. Its active metabolite is unknown, and its mechanism of action is unclear [5,6]. Current studies show that it seems to act as a partial agonist of serotonin receptors and opioid receptors, and that it seems to have a dopaminergic effect as well [17]. In 2012, a review by Cochrane analyzed 16 randomized controlled clinical trials on 2027 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who were treated with 40mg of cimicifuga racemosa for 23 weeks. No significant differences were found in the decrease of hot flashes between the women who received treatment and the placebo group [20]. No drug interactions are known, although it may interfere with tamoxifen [10]; however, since its mechanism of action is unknown, its concomitant use with hormone therapies is not recommended in women with a personal history of hormone-dependent cancers.

Pharmacological Strategies

Clonidine, a central action alpha 2-adrenergic agonist, acts by decreasing the secretion of noradrenaline in the synaptic space [21]. A 10-study meta-analysis showed that clonidine is slightly more efficient than placebo in reducing vasomotor symptoms with a 46% efficacy in the reduction of hot flashes. Its use has been associated with several significant adverse effects, such as dry mouth, dizziness, hypotension, constipation and sedation, therefore its current clinical use has been limited [22]. Gabapentin, a gamma-aminobutyric acid, regularly used as treatment for epilepsy and chronic neuropathic pain, has shown to be efficient in reducing hot flashes in breast cancer patients [23]. It has no drug interactions, does not cause sexual dysfunction and seems to be well tolerated. The recommended dose for the treatment of hot flashes is 900mg/day [24]. As for adverse events, patients report drowsiness, dizziness and some anhedonia, which appear following the first week of treatment and resolve without treatment by week four of use [25].

Pregabalin is a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogue with the same indications as gabapentin. A randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled study comparing 75mg twice daily or 150mg twice daily of pregabalin and placebo found, after 6 weeks, a 65% and 71% improvement in the reduction of hot flashes with pregabalin, depending on dose. As for adverse effects, insomnia, dizziness and weight gain were observed; it is important to note that some women experienced cognitive dysfunction at higher doses [26]. SSRIs and SNRIs are groups of drugs that have been widely studied for the treatment of VMS, especially in patients who have had breast cancer. Although their mechanism of action is unclear, it has been proposed to enhance serotonergic neurotransmission by its selective inhibition of serotonin reuptake, as well as its concentration at the hypothalamic level, through the activation of the 5HT2 receptor. Their benefit on VMS appears independently of their antidepressant effect and much earlier than with other therapies [27]. They have proved to reduce hot flashes with a variability between 25-69%. Although patients inform some adverse effects, such as headaches, nausea, loss of appetite, gastrointestinal intolerance and sleep disorders among others, they are not usually observed at low doses, being a well-tolerated alternative. [28,29]

Depression and mood alterations are common after a breast cancer diagnosis. The use of a low dose of these pharmacological agents may notably improve the quality of life for these women [30]. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial [20] with venlafaxine, an SNRI, in increasing doses of 37.5, 75, and 150mg/day in patients with breast cancer who took tamoxifen, it was observed that, after four weeks, hot flashes scores had a rapid and significant 37% and 61% decrease, depending on dose. There was no drug interaction in the metabolism of tamoxifen [32]. The International Menopause Society (IMS) does not recommend the use of fluoxetine or sertraline due to the fact that no significant reduction in vasomotor symptoms was found in placebo-controlled studies [33]. Some drugs may interfere with the transformation of tamoxifen into its active metabolite, 4-hydroxy-desmethyltamoxifen (endoxifen), by inhibiting cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) [34].

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies these psychiatric drugs into strong, moderate and weak inhibitors, according to their interaction with cytochrome P450. Both paroxetine and fluoxetine have been classified as strong inhibitors; sertraline as a moderate inhibitor; and citalopram, escitalopram, venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine as weak inhibitors [35]. The American Clinical Oncology Society recommends avoiding the use of antidepressants classified as strong inhibitors [35], considering venlafaxine and escitalopram as the best option for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in these patients [36]. Escitalopram, an SSRI with weak effect on noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake, at increasing doses has shown a 55% reduction in hot flashes in menopausal women or women in the menopause transition, with 4% of side effects and a 70% satisfaction rate [37]. Our experience in the Climacteric Section of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires with the use of escitalopram at 5mg and 10mg doses in patients with severe hot flashes, a history of breast cancer, or with a contraindication for MHT, was similar or even superior to the percentages of most published studies. Our results have indicated a 60% reduction by week 1, which is progressively maintained after one year of use, with good compliance and few side effects.

In the year 2013, the FDA approved the use of paroxetine at 7.5mg doses as treatment for hot flashes. The efficacy of paroxetine was established in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trials. Among a total of 1184 menopausal women who had a median of 10 moderate-to-severe hot flushes per day, paroxetine 7.5mg was shown to provide significant relief in comparison to placebo [38]. In the summarized literature, in fact, in breast cancer survivors paroxetine was associated with a 40%–67% reduction in hot flashes frequency [39]. The benefits were observed in 1-2 weeks of treatment, persisting for 6 weeks. Regarding sleep, paroxetine significantly reduces hot flashes in weekly frequency and severity and the number of nighttime awakenings attributed to vasomotor symptoms, increasing sleep duration. These improvements occur without increased sedation, suggesting that paroxetine has a selective therapeutic effect on sleep parameters related to VMS [40,41]. In the year 2015, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) [42] published their position statement on the nonhormonal management of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. The NAMS panel concluded that the recommended therapies for menopausal and postmenopausal hot flashes are paroxetine 7.5-10-25mg/day; escitalopram 10-20mg/ day; citalopram 10-20mg/day; desvenlafaxine 50-150mg/day; and venlafaxine XR 37.5-150mg/day.

Conclusion

Vasomotor symptoms significantly affect the quality of life; therefore, offer alternative strategies in women with a need for non-hormonal treatment resulting mandatory, since the ultimate goal is to improve our patient’s quality of life.

References

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, Bromberger JT, Everson-Rose SA, et al. (2015) Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 175(4): 531-539.

- Dennerstein L, Smith AM, Morse C, Burger H, Green A, et al. (1993) Menopausal symptoms in Australian women. Med J Aust. Aug 16 159(4): 232-236.

- Freeman E, Sammel M, Grisso J, Battistini M, Garcia-Espagna B, et al. (2001) Hot flashes in the late reproductive years: Risk factors for African American and Caucasian women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 10(1): 67-76.

- Del Re M, Citi V, Crucitta S, Rofi E, Belcari F, et al (2016) Pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 and tamoxifen therapy: Light at the end of the tunnel? Pharmacol Res 107: 398-406.

- Mintziori G, Lambrinoudaki I, Goulis DG, Ceausu I, Depipere H, et al. (2015) EMAS position statement: Non-hormonal management of menopausal vasomotor symptoms. Maturitas 81(3): 410-413.

- Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society 22(11): 1155-1174.

- Butler C, Chapman E, Forman M, Beck AT (2006) The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev 26(1): 17-31.

- Mann E, Smith M, Hellier J, Hunter MS (2011) A randomised controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural intervention for women who have menopausal symptoms following breast cancer treatment (MENOS 1): trial protocol. BMC Cancer 11: 44.

- Ayers B, Smith M, Hellier J, Mann E, Hunter MS (2012) Effectiveness of group and self-help cognitive behavior therapy in reducing problematic menopausal hot flushes and night sweats (MENOS 2): a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 19(7): 749-759.

- Jane Woyka (2017) Consensus statement for non-hormonal-based treatments for menopausal symptoms. Post Reproductive Health 23(2): 71-75.

- Elkins G, Marcus J, Stearns V, M Perfecto, Rajab MH, et al. (2008) Randomized trial of a hypnosis intervention for treatment of hot flashes among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 26(31): 5022-5026.

- Elkins GR, Fisher WI, Johnson AK, Carpenter JS, Keith TZ (2013) Clinical hypnosis in the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 20(3): 291-298.

- Saensak S, Vutyavanich T, Somboonporn W & Srisurapanont M (2014) Relaxation for perimenopausal and postmenopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20(7).

- Dodin S, Blanchet C, Marc I, Ernst E, Wu T, et al. (2013) Acupuncture for menopausal hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 30(7).

- Chiu HY, Pan CH, Shyu YK, Han BC, Tsai PS (2015) Effects of acupuncture on menopause-related symptoms and quality of life in women in natural menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 22(2): 234-244.

- Taku K, Melby MK, Kronenberg F, Kurzer MS, Messina M (2012) Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 19(7): 776-790.

- Borrelli F, Ernst E (2010) Alternative and complementary therapies for the menopause. Maturitas 66(4): 333-343.

- Lethaby A, Marjoribanks J, Kronenberg F, Roberts H, Eden J, et al. (2013) Phytoestrogens for menopausal vasomotor symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12).

- Sirotkin A, Harrath A (2014) Phytoestrogens and their effects. European Journal of Pharmacology 741: 230-236.

- Leach MJ, Moore V (2012) Black cohosh (Cimicifuga spp.) for menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9).

- Pandya KJ, Rauberta RF, Flyn PJ, Hynes H, Rosenbluth R, et al. (2000) Oral clonidine in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer experiencing tamoxifen- induced hot flashes: a University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program study, Ann Inter Med 132(10): 788-793.

- Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E Rongwei F, Nedrow A, Milleret J, et al. (2006) Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis, JAMA 295(17): 2057-2071.

- Pandya K, Morrow G, Roscoe J, Zhao H, Hickok J, et al. (2005) Gabapentin for hot flashes in 420 women with breast cancer: a randomised doubleblind placebo-controlled trial, The Lancet 366(9488): 818-824.

- Reddy SY, Warner H, Guttuso T Jr, Messing S, DiGrazio W, et al. (2006) Gabapentin, estrogen, and placebo for treating hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial, Obstet Gynecol 108(1): 41-48.

- Butt DA, Lock M, Lewis J, Ross S, Moineddin R (2008) Gabapentin for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial, Menopause 15(2): 310-318.

- Loprinzi CL, Qin R, Balcueva EP, Flynn K, Rowland K, et al. (2010) Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of pregabalin for alleviating hot flashes NO7C1, J Clin Oncol 1 28(4): 641- 647.

- Stearns V (2007) Clinical update: new treatments for hot flushes, Lancet 369(9579): 2062-2064.

- Speroff L, Gass M, Constantine G, Olivier S (2008) Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine succinate treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial., Obstet Gynecol 111(1): 77- 87.

- Bardia A, Novotny P, Sloan J, Barton D, Loprinzi C (2009) Efficacy of nonestrogenic hot flash therapies among women stratified by breast cancer history and tamoxifen use: a pooled analysis, Menopause 16(3): 477-483.

- Eden J (2016) ENDOCRINE DILEMMA: Managing menopausal symptoms after breast cancer, Eur J Endocrinol. Mar 174(3): 71-77.

- Loprinzi C, Kugler J, Sloan J, Mailliard J, LaVasseur B, et al. (2000) Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial, Lancet 356(9247): 2059-2063.

- Jin Y, Desta Z, Stearns V, Ward B, Ho H, et al. (2005) CYP2D6 genotype, antidepressant use, and tamoxifen metabolism during adjuvant breast cancer treatment, J Natl Cancer Inst 97(1): 30-39.

- Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A (2016) IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy, Climacteric 19(2):109- 150.

- Regan MM, Leyland-Jones B, Bouzyk M, Pagani O, Tang W, et al. (2012) CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: the breast international group 1-98 trial, J Natl Cancer Inst 104(6): 441-451.

- Irarrazaval M, Gaete L, (2016) Mejor eleccion de antidepresivos en pacientes con cancer de mama y tamoxifeno: revision Rev Med Chile 144: 1326-1335.

- Kelly CM, Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Duong-Hua M, Pritchard KI, et al. (2010) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: a population based cohort study, BMJ 8: 340.

- DeFronzo Dobkin R, Menza M, Allen L, Marin H, Bienfait K, et al. (2009) Escitalopram reduces hot flashes in nondepressed menopausal women: A pilot study, Ann Clin Psychiatry 21(2): 70-76.

- Simon J, Portman D, Kaunitz A, Mekonnen H, Kazempour K, et al. (2013) Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal VMS: two randomized controlled trials, Menopause Oct 20(10): 1027-1035.

- A Bardia, P Novotny, J Sloan, D Barton, C Loprinzi (2009) Efficacy of nonestrogenic hot flash therapies among women stratified by breast cancer history and tamoxifen use: a pooled analysis, Menopause 16(3): 477-483.

- Capriglione S, Plotti F, Montera R, Luvero D, Lopez S, et al. (2016) Role of paroxetine in the management of hot flashes in gynecological cancer survivors: Results of the first randomized single-center controlled trial, Gynecologic Oncology 143(3): 584-588.

- Pinkerton J, Joffe H, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, et al. (2015) Low-dose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 22(1): 50-58.

- Carpenter J, Gass M, Maki P, Newton K, Pinkerton J, et al. (2015) Nonhormonal management of menopause-Associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 22(11): 1155-1172.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...