Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Victimization, Suicide and Coping Among Vulnerable Slum Youth in Uganda During Covid 19 Crisis Volume 5 - Issue 5

Rogers Kasirye and Barbara Nakijoba*

- BA Social Work and Social Administration and master’s Candidate-Barbara Nakijoba, Makerere University, Uganda

Received:August 19, 2021 Published:September 07, 2021

Corresponding author:Barbara Nakijoba, BA Social Work and Social Administration and master’s Candidate-Barbara Nakijoba, Makerere University, Uganda

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.05.000221

Abstract

Urban young people face a myriad of problems and during COVID 19 this may have worsened. This study examined the factors associated with suicide, victimization, and coping among youth living in the city and urban towns Uganda. Analyses are based on cross-sectional survey data, collected in 2020, of a convenient sample (n = 583) of rural and urban youth UYDEL beneficiaries of the DREAMS Project at different UYDEL safe spaces. Of the 583-youth interviewed, 21% reported experiencing suicidal ideation in their lifetime. Victimization was also high at 52%. Our findings shed more light on the unmet need of this vulnerable population. However, strategies that specifically seek to address, youth employment, parental factors, problem drinking a modifiable risk factor for suicidal ideation may be particularly warranted in this low-resource setting. NGOs.

Keywords: Victimization; Suicide; Coping Vulnerable Young

Introduction

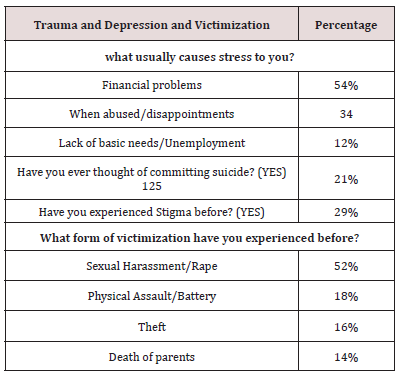

Suicide and victimization are a major public health problem worldwide and the third leading cause of death for adolescents ages 15-19 [1]. While there is a scarcity of literature on suicidality and associated risk factors in sub-Saharan Africa, there is a growing recognition of the problem and also of suicidal ideation as a pressing problem. To-date, most of the previous literature has focused on suicidal behavior and ideation in high-income Western countries. As an example, in the United States, an estimated 17.0% of high-school youth have reported suicidal ideation in the past year, whereas reports of suicidal ideation among youth in Uganda are much higher (27.9%) [2]. Moreover, youth living in the slums or on the streets may be at an even higher risk for both suicidal behaviors and ideation, which may be exacerbated by their dire environmental conditions. A previous study documented a 30.6% prevalence of suicidal ideation among youth living in the slums of Kampala and rural communities in Uganda [3]. While there may be unique risk factors for suicidal behaviors and death among youth in sub-Saharan Africa, there are likely also similarities to those of adolescents in other regions of the world. Previous research shows that being homeless, substance use, adverse childhood experiences, and HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are important risk factors for suicidality among youth. Youth reported stress and depression to result from deprivation in terms of lacking basic needs and financial support. 29 % of the beneficiaries reported experiencing stigma. Girls reported being victimized by their male counterparts in form of sexual harassment and for them this was a major cause of stress and depression. Poverty has been linked to suicidal ideation as it results into deprivation and exposes youth to engage in risky adaptive behaviors for survival which include transactional sex, early sexual involvement which in turn exposes them to both physical and emotional abuse [4]. These traumatic experiences have been linked to an increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior [5]. Substance use in particular alcohol use and misuse such as problem drinking and drunkenness has also been well-established in the literature as having an association with suicidal ideation and attempt among adolescents; however, few studies have examined these associations in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Uganda, suicidal ideation and behaviors have been identified as an emerging public health problem among adolescents, particularly among youth in dire environmental conditions such as youth being homeless and slums of Kampala [6-9]. Some of the unique vulnerabilities of youth in the slums are related to living in absolute poverty without adequate access to clean water, electricity, and sanitation, and also exposure to high levels of crime including violent victimizations [10]. Slum communities are typically characterized by their lack of basic infrastructure, government resources, and social services. Additionally, slums consist of a broad range of poor environmental, social, and economic conditions which likely exacerbate the mental health conditions of vulnerable youth who experience a multitude of other risk factors and adversity [11]. To add to the limited research on suicidal ideation among youth in slums, the current study examines the psychosocial risk factors for suicidal ideation in a relatively large cross-sectional study of youth living in the District towns in Luwero, Mityana, Wakiso and Kampala Districts (n = 583). This study expands on the research presented previously from a smaller study, also conducted in the slums of Kampala in 2018, by examining the risk factors for suicide ideation in a sample with a narrower age (10-24 years) range. The current analyses focus on key demographic characteristics and psychosocial factors, several of which were not addressed in the previous study (i.e., age, gender, education, parental status, nature of family, trauma, depression, victimization, suicide, online child sexual exploitation, trafficking, livelihood and economic survival, alcohol, and substance use, and it explores the impact of COVID 19 on this population. ever being homeless, parental living status, alcohol and problem drinking, HIV infection, STI infection, ever being raped, and parental physical abuse of the youth). Our hypothesis is that homeless, problem drinking, HIV and STI infection, previously being raped, and physical child abuse will be associated with suicidal ideation. The goal of this research is to provide new empirical data on suicide ideation among vulnerable youth in the slums while also providing information that can guide service provision and the development of interventions for youth in low-resource settings. Uganda has never experienced a pandemic of this magnitude, HIV AIDS didn’t devastate the communities as COVID 19 and such we have not developed skills nor interventions to respond appropriately to the negative impact of the Pandemic. Specifically, we don’t have a clear idea in such a situation how children cope and navigate through life during this Pandemic. Most of the available studies are from the western world. Available studies do not provide a comprehensive localized response mechanism, and to worsen matters, the strain of the Pandemic keeps changing which negatively impacts progress on identification of response mechanisms that work. By contrast what is reported here we have less information on suicide, victimization and coping in such a cohort of vulnerable groups and other adjunct risk behaviors. This study fills the literature gap in urban young people in a low resource country setting. It adds some more information on how such young people living in towns cope and can be helped to further improve their lives.

Methods

Study design

The current study is based on the cross-sectional survey conducted in September 2020 to map risk behaviors in which youth in Uganda are engaged, with a focus on alcohol use, sexual behaviors, and HIV. The sample consisted of 583 rural and urban service-seeking youth, 10-24 years of age, living in the slums or on the streets of Kampala, Uganda, who were participating in a Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL) drop-in center for disadvantaged youth. Study participants were recruited at the UYDEL safe spaces and the neighborhoods surrounding the Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL) safe spaces through local leaders, and each interviewed by a social worker from UYDEL. For all interviews conducted, informed consent was sought from the study participants.

Data collection

Survey data collection methodology was used and overall youth participants (ages 10-24) with 583 completed surveys which were submitted in Kobo toolkit. Participants were informed about the study. All participants provided verbal consent to participate in the study. This is because youth who “cater for their own livelihood” are considered emancipated in Uganda and are able to provide their own consent for the survey without parental consent. Participation was limited to youth ages 10-24 present in-person on the day of the field visit and those in the communities who were willing to walk into the safe spaces. There were no other exclusion criteria. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted as part of follow up which is part of programming therefore we did not seek approval for conducting the study.

Quality control and data management and analysis

This study adapted a standardised questionnaire (HEADES tool) developed by https://depts.washington.edu/dbpeds/ Screening%20Tools/HEADSS.pdf. The survey included questions; age, gender, education, parental status, nature of family, trauma, depression, victimization, suicide, online child sexual exploitation, trafficking, livelihood and economic survival, alcohol and substance use, and it explores the impact of COVID 19 on this population. While most of the original items were kept, the tool was modified with UYDEL social workers to suit the urban and rural town study context and later approved by the Senior management for administration. Data was collected by a team of well-trained social workers. These social workers received training on research ethics to ensure that the study complied with the principles of ‘do no harm’ to young people participating in the study. Additional training was done about how to seek consent, confidentiality of information, privacy of information. It was pretested in Mukono municipality 20 miles away from the study area. All question as were clarified and made clear. The questionnaire was uploaded on handheld tablets using the Kobo Collect toolbox. Quality checks were inbuilt in Kobo Collect toolbox to ensure consistency during data collection. Social workers together with their supervisors crosschecked for errors in the data while still in the field. After the data collection exercise which took three weeks in the month September 2020, data was downloaded from the server and exported into Stata for further analysis.

In stata quantitative analysis involved the following:

a) Data exploration and management to identify missing data, label variables, re-coding, rename, etc

b) Undertake descriptive analysis with frequency tables for categorical variables

c) Univariate analysis using frequency tables, summary stats, i.e., demographic and sexual behavioural characteristics

d) The level of statistical significance was set at a probability of P < 0.05 for all tests.

Measures

The main outcome variable suicidal ideation was measured using the following question, “Have you ever thought of committing suicide?” Respondents could answer “Yes” or “No”. “What form of victimization have you experienced before?” Respondents could answer Sexual “Harassment/Rape”, “Physical Assault/Battery”, “Theft”, and “Death of parents”. Sociodemographic variables included gender (male or female), age, parental status (Both parent living, Single parent, Orphans), and education (primary, O level, Tertiary/ A Level). Hypothesized risk factors were ascertained from previous studies and the growing body of literature on suicidal ideation among youth in developing countries. The questionnaire themed around these hypothesized risk factors was developed and used to collect data.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for suicidal ideation. Descriptive statistics were also computed for sociodemographic variables and hypothesized risk factors among outcome categories (suicidal ideation vs. no suicidal ideation). Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to determine the association between suicidal ideation and the hypothesized risk factors, adjusting for sociodemographic variables. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Sample size and sociodemographic features of study participants

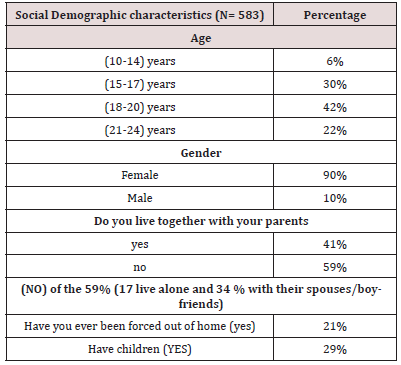

A total of 583 adolescents and young people took part in the quantitative component of the study (Kampala city and Luwero town [Districts]) of which 90% were females and 10% males. Majority (42%) of the respondents lay between age category 18- 20 years of age with the majority (52%) educated up to primary level. Majority of the population (48%) came from monogamous families and (39%) from polygamous families. 59% said they were not living together with their families at the time of the interview. Of these, 17% said they lived alone and (34%) with their spouses/ boyfriends. 21% had ever been forced out of the home and 29% said they had children. We saw a mixture of parental status and residences) More information on these and more sociodemographic variables is captured in Table 1. Suicidal ideation. Among the youth participants (n = 583), 125 (21.4%) reported having ever had suicidal ideation. While the overall sample was comprised of mostly females (90%), a larger number of females reported suicidal ideation (116) compared to the total sample.

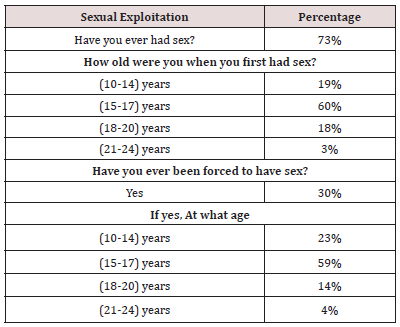

Casual factors: A much higher percentage of youth who reported suicidal ideation reported experiencing stress as a result of having financial problems, physical and emotional abuse. In addition to the lockdown period due to the COVID 19 Pandemic Sexual harassment was one of the triggers for suicide and overall However, this is in contrast with what was reported by Rukundo et, al (2020) in their study regarding Prevalence and risk factors for youth suicidality among perinatally infected youths living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. In their findings, they stated that risk of suicide is more among persons with HIV/AIDS even in the presence of the highly active antiretroviral therapy. 52% of the respondents reported victimization in terms of sexual harassment and rape. 73% of the young people interviewed had ever had sex. However, when asked age when first had sex 19% had their first sexual encounter between the age of (10-14years). Among the 30% who had ever been forced to have sex, 23% were between the age of (10- 14 years).

Victimization

There is a pattern of victimization imbedded in terms of sexual harassment and their vulnerability due to their limitation, poverty, lack of family support, environment and. Survivors of rape are more likely to attempt or commit suicide.

Casual factors

Sexually abused suicide attempters showed more suicidal behavior than their non-sexually abused counterparts. Children living under child headed households or with boyfriends (59%) were more predisposed to stress expressed limited in social stress support. Parental support is a key protective factor. When children stay alone they do not get full attention. And when children are chased out of the home it increases their stress levels and exposure to abuse and other risks that result into suicidal ideation. Furthermore, children are more at risk of exploitation and initiation into antisocial behavior when they are living alone by friends, 62% of the respondents were introduced to transactional sex by friends and 87% were having between (1-5) sexual partners. A higher percentage of suicidal youth reported alcohol use (43%). Additionally, a higher percentage of suicidal youth reported giving birth (47%) at an early age (15-17 years), which increases stress, suicidal tendencies. Most victimization occurred mostly to age category 15-17 years (59%). Majority of the perpetuators were Friends and Boyfriends to the victims (39%) who were well known to them. This is almost similar to findings in the VAC study that states that perpetuators were most often friends (25.6%). Having children when one is still very young is burdensome that it causes an individual to take on two roles at the same time that is; one has to be a parent and a child at the same time which results into stress.

Coping and impact of COVID 19

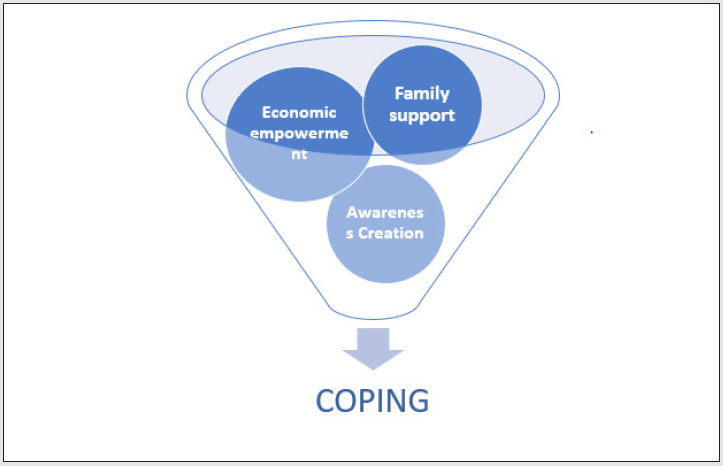

COVID 19 had a more devastating impact and heighten the vulnerability of girls further as far as coping was concerned. Almost a half 48% felt disappointed/hopeless and another 47% worried and stressed. These two situations probably have been intense with some girls 125[21.4%] who experience suicide ideation. Many faced situations of violence and harassment (33%) in form of sexual abuse, beating, neglect and many confessed to facing many challenges (77%) particularly food 56% and lack of money 44%. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda inclusive, implemented lockdowns, curfew, banning of both private and public transport systems, and mass gatherings to minimize spread. 48% of the respondents were left homeless by the lengthy lockdown. Businesses closed down and majority of families that were childheaded and survived on hand to mouth basis became distressed (47%). Parents stayed home, worried sick with uncertainty about when they might be able to go back to work and earn some income to sustain their families. Social control measures for COVID-19 are reported to increase violence; (19%) sexual abuse, (25%) beating, and (20%) neglected. Respondents reported 56% lacked what to eat and 44% faced financial shortages as a result of not being able to work. However, relief food distribution during the lockdown stood out as a strategy that worked to offset the negative impact of the lockdown. During COVID 19, (64 %) received some form of help a in form of food and money. Another 36 received nothing. Help largely came from NGO-UYDEL and relatives (71%). To some positive adaptation and adjustment during corvid was difficult it may have led to transactional and survival sex, use of drugs and crime. However, they requested additional support to enable them bounce back on their feet in terms of, accessing employment opportunities (63%) and 13% preferred empowerment through vocational skills training (Figure 1).

High-risk sexual behaviours among adolescents and young people in Kampala

Table 2 provides a summary of the high-risky sexual behaviours that young people in Kampala engaged which include sexual activeness, age of sex debut, coping, transactional sex, HIV knowledge and teenage pregnancy, and drugs, Alcohol and Substance Use.

Sexual activeness

Almost 73% of the respondents were sexually active and a heightened sexual act during covid19-a (Figure 2) comparable to 62% reported by Renzaho et al (2017) among young people in the areas of Lubaga and Makindye, Kampala. Majority (60%) had early sexual debut between 15-17 years. This is similar to Figures 1&2 reported by the Alan Guttmacher Institute for young people within similar age categories; Half of Ugandan women and nearly four in 10 men aged 15–19 have ever had sex. Among 18–19-yearolds, this proportion is much higher for both sexes: 77% and 59%. These findings imply greater inclination for your people to engage in sexual practices mainly transactional sex. Similar to Asingwire, et.al, (2016) this study demystifies the ability of young people withholding their sexual urges even with the existence of strong traditions that are expected to discourage young people from engaging in pre-marital sexual practices and behaviors (Table 3).

Age of sex debut

The average age of sexual debut was 17 years. This is similar to the national average of 17.1 years as reported by the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS 2018). It is important to note however that in our sample 30% had ever been forced to have sex out of their will. Majority (59%) who were forced to have sex were between the ages of 15-17years. 39% had been forced by boyfriend, 34% by client /stranger, 16% by relative/guardian, and 11% by employer/workmate. Of these, only 29% reported the abuse. Early sexual debut is more about forced sex and violence against children 10-14 years 19% of the study participants. According to the VAC study children who experienced sexual abuse in terms of forced sex (girls, 10.0%; boys, 2.0%).

Coping amongst the urban slum youth

We established that there a lot of negative coping amongst these groups especially heightened sexual involvement, transactional sex, engagement in multiple sexual partners; use of alcohol and substance abuse; tendency of criminality this may have a bearing on suicide and victimization (Table 4)

Transactional Sex

46% had engaged in Transactional sex before COVID 19 Crisis in relation to the 31% during the COVID 19 crisis. Majority (62%) had been introduced to Transactional sex by their friend. Only 30% had introduced themselves to the vice. 87% had between 1-5 sexual partners. 57% of these said they have many partners usually during weekends and public holidays. 66% acknowledged that sexual exploitation acts are known to happen in hotels and lodges. The children engaged in transactional sex for survival purposes; some were given money and other in-kind items.

HIV knowledge and teenage pregnancy

Majority (86%) had ever tested for HIV and knew their serostatus. 29% had children and majority (47%) became parents during the age category of 15-17 years. This is similar to data reported by UNFPA on their Adolescents and Youth Dashboard – Uganda that captured; 33% gave birth before the age of 18 years. 29% had children and majority (39%) had children between the age of 15-17 years.

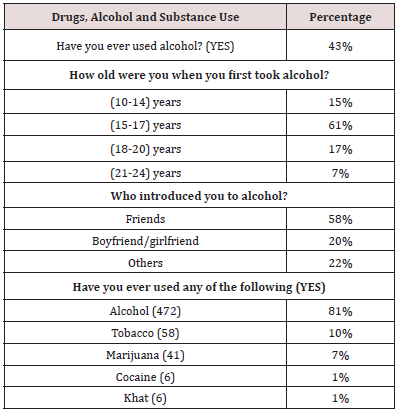

Drugs, alcohol and substance use

The data showed that 43% of youth had ever used alcohol. Majority (81%) were using alcohol followed by Tobacco (10%) and Marijuana (7%), Khat (1%) and Cocaine (1%) were the least abused. A similar study conducted in Kampala by Culbreth et, al. 2018, had differing results; drugs most abused in the area were Khat 52.6%, followed by alcohol abuse 25.6%, marijuana 15.4% and cocaine 6.4% and then use as the least drug abused was heroin at 2 (0.8%). Majority (61%) between the age of 15-17 years. Majority (58%) were introduced by friends. Majority of our study participants 90% females used more alcohol which is very common amongst females compared to other drugs. This is also related to Transactional sex where alcohol helps to reduce the stress associated with engagement with multiple partners.

Suicide among urban children in uganda

Ongoing family conflicts, abuse, violence, lack of family connectedness, and parents’ mental health problems can also raise a child’s suicide risk. Changes that involve loss, such as a death of a loved one or family homelessness can put a child at higher risk. Our findings highlighted the following as causal factors for suicide among children. Causes of Suicide; Parental factors, Alcohol abuse, Unemployment, Stigma, Negative effects of COVID 19, Environment, Childhood abuse/History, Peer Factors/Survival needs. Therefore, violence, abuse, stigma and other negative childhood experiences in communities where children grow up result into a cycle of victimisation which later on may result into suicide among young adults.

Positive Coping

Being young isn’t easy. The teenage years are accompanied by a number of stressors and significant life stages. Throw into the mix the hormonal changes that accompany puberty and an increasing need to fit in with their peers, and it’s no wonder that young people often find their adolescent years stressful and overwhelming. To tackle the difficulties that come with being a young person, it’s crucial to encourage young people to develop positive coping strategies. According to UYDEL, the following is what consists of a positive coping mechanism; spirituality, economic empowerment. Friends, sports, music, dance and drama, and family support. This study may have been limited as it was cross-sectional and used a convenient sample of children being served by UYDEL in the DREAMS project limiting us to make causal inferences about our conclusion and probably studies in other urban towns would also give us different results.

Discussion

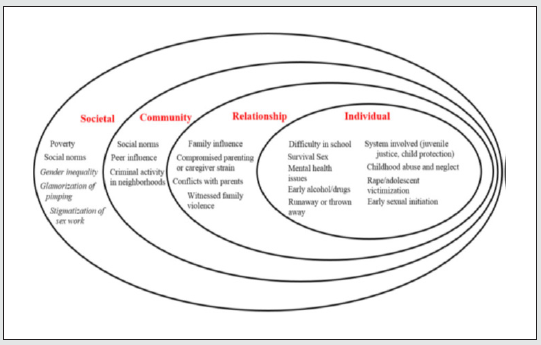

Urban youth face a myriad of problems and during COVID 19 this may have worsened. This study examined the factors associated with suicide, victimization, and coping among youth living in the city and urban towns Uganda. Analyses were based on cross-sectional survey data, collected in 2020, of a convenient sample (n = 583) of rural and urban youth UYDEL beneficiaries of the DREAMS Project at different UYDEL safe spaces. Our findings shed more light on the unmet need of this vulnerable population. Of the respondents interviewed, who had ever experienced victimization reported victimization in form of sexual harassment (52%), Physical assault (18%) and as a result 21% struggled to heal from this form of harm and experienced suicidal tendencies. The age category 15-17 years was more at a heightened risk of being sexually exploited. It was also noted that alcohol and substance abuse played a crucial role in increasing the risk of victimization amongst this age category, as majority were actively abusing drugs (61%). However, what enhanced coping among the category who experienced harm in terms of victimization or suicide was giving them tools to facilitate recovery from harm and this was majorly in terms of economic empowerment and psychosocial support (SAMHSA, 2021). Their families were also supported with parenting skills and some form of income generating activity to facilitate sustainability of the interventions. There was also massive awareness creation and community engagements to facilitate a supportive environment for coping and reduce harm for other youth within the communities. A holistic and cross discipline response to vulnerabilities associated with exploitation, victimization, and suicide is required. Findings suggest that responses be based on the Ecological framework that seeks to address the multiple influencing factors of risky behaviors and the belief is that these behaviors are shaped by interactions within and across these levels, this model helps organize the complex and interacting factors that place minors at risk of exploitation [12-15].

Majority of existing studies focus their understanding on a few causes of suicide. For example, according to a recent study, in their findings reported that substance abuse and psychological stress are significant factors associated with suicide ideation and attempt among adolescents living in urban areas in Kampala. This slightly differs from findings of this study which identifies numerous risk factors that increase a minor’s vulnerability to suicide. Some key points regarding these risk factors include that, according to published research, many exploited minors have a prior history of child abuse, neglect, and/or maltreatment, which potentially heightens their vulnerability to exploitation [16]. Childhood sexual abuse as our data shows is frequently singled out a particularly salient risk factor among the categories of abuse as it can damage a child’s coping skills, damage their trust of and relationship with caregivers, and possibly motivate criminal, risky, or harmseeking behaviors during adolescence [17]. Running away (or being thrown away) as a youth seems to place them at high risk of experiencing exploitation and abuse, especially considering the material need such upheaval creates [12]. Additionally, a negative home environment brought about by factors such as compromised parenting, caregiver strain, or witnessing family violence is associated with exploitation, as is the influence of their social network via peer or family member involvement in trading sex [7]. These commonly cited risk factors, along with others, and their nuances are discussed further [2]. It is important for the risk factors of suicide to be understood from a holistic perspective. At the individual level, many of the risk factors are inflicted on or experienced solely by the vulnerable minors, including difficulties during childhood (childhood abuse and neglect; involvement in the systems of juvenile detention or child protection adolescent rape or sexual victimization, early substance use, poor mental health, problema history of running away, and involvement in survival sex to support themselves. Relationship factors include elements of a minor’s home life or general environment such as family influence in many of our cases represented a mixture i.e living parents other with relatives and alone so this may not necessarily be a factor as this is takin many shapes, compromised parenting/caregiver strain, conflicts with parents, and witnessing family violence. Community factors entail social norms, peer influence, and general criminal activity in neighborhoods which may be witnessed by children and youth high in urban centers and slums. Social norms fit in both the community and societal levels, as they can be contextualized and reinforced within individual communities while also being constructed in the larger dominant society. The societal level also captures poverty or material need as well as factors not measured by any of the reviewed studies here but which are noted in the literature to reinforce or encourage CSEC/DMST; these are gender inequality, glamorization of pimping, and the stigmatized nature of sex work [11]. Keeping in mind the revictimization theory which states that individuals who experienced abuse are more likely to experience victimization again later in life [14]. Given the significant influence of childhood abuse on creating a vulnerability for exploitation, this theory fits within a potential pathway leading from childhood to commercial exploitation/domestic minor trafficking when an individual fall into exploitation by a third party or via their need to engage in survival risky behavior.

Implication and Conclusion

In spite of the limitations on population interviewed served by UYDEL and possible biases that can arise This population under study, all experienced a lot of challenges in suicide, victimization and coping. Suicide ideation was high and real. Out of every 5 young people interviewed, one experienced suicide. Victimization also worsened their situation as rape and beating and was reported high. when transactional sex survival violence, alcohol use. Corvid made their lives difficult, and coping was hard as they face many challenges family strain, witnessing violence, no employment and lack of food. Participants as much as tried to seek support to cope this was not forthcoming and many resorted to negative coping involving transactional unprotected and survival sex, alcohol and substance abuse and survival crime. This also worsened as many were victimized and forced into rape, beating and other abuses weak position and lack of knowledge where to report compounding suicide and victimization. Social and other interventions were scarce. This was a time when there is limited family attention, service availability, escalated poverty and absence of social safety nets and social protection as family members are busy looking to make ends meet in a lock down. There is need to tap into social support from the communities and peers in a positive way rather than the quick negative ways of coping including use of alcohol and transactional.

In order to reduce such vulnerability young people, need to be absorbed in employment sector to get jobs (63%) in order to deal with most challenges, provide food and vocational skills. This will enable them to positively cope and reduce risks that makes them prone to suicide, transactional sex and alcohol and drugs.

There also need for a policy and programme actions that require first that address the need to help young people become multiskilled to improve income and employment opportunities; develop skills to deal with suicide ideation and involve parents. Address culture that perpetuate victimization and prosecute offenders Substance abuse education and life skills to help them increase positive ability to survive with less negative exploitation in child labor and conventional crimes like rape, assault and other habits like abuse and neglect and simple crimes that lead them to be arrested in police cells.

NGOs need to be helped to develop robust holistic, integrative social protection programs that alleviate the poverty levels in urban centers; increase opportunities for slum youth to learn multiple vocational skills and access to cash transfers, initiate parental programs and psycho social support activities that address individual limitations and risky sexual behavior, suicide, alcohol and substance abuse and homelessness and stigma. Forward planning and flexibility in modes of interventions for those most deserving is also key as fragmented interventions can lead to overlap, competition and wastage of resources. There was also a lot of barriers in accessing social and health services mainly instated by Government in planning national lockdowns and intervention needs to discussed thoroughly as the consequences of this are too many. Not all safe spaces should close in such emergencies as Uganda Government appear to have directed, safety nets must remain functioning to address such ills and also give young people a place of refuge, we need to absorb children facing victimization in such low poor communities.

Funding

This study was funded by internal resources from UYDEL, no other grant was received.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Bukuluki P, Wandiembe S, Kisakye P, Besigwa S, Kasirye R (2021) Suicidal Ideations and Attempts Among Adolescents in Kampala Urban Settlements in Uganda: A Case Study of Adolescents Receiving Care From the Uganda Youth Development Link. Front Sociol 6:

- Cash S J, Bridge J A (2009) Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr 21(5): 613-619.

- Chohaney M L (2016) Minor and adult domestic sex trafficking risk factors in Ohio. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 7(1): 117-141.

- Culbreth R, Swahn M H, Ndetei D, Ametewee L, Kasirye R (2018) Suicidal Ideation among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(2): 298.

- Davis K (2019) Perceptions and Precarity of the Urban Poor in Kampala, Uganda. University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA.

- Edwards L, Mika K M (2017) Advancing the efforts of the macro-level social work response against sex trafficking. International Social Work 60(3): 695-706.

- Franchino Olsen H (2019) Vulnerabilities relevant for commercial sexual exploitation of children/domestic minor sex trafficking: A systematic review of risk factors. Trauma Violence Abuse 22(1): 99-111.

- Landers M, McGrath K, Johnson M H, Armstrong M I, Dollard N (2017) Baseline characteristics of dependent youth who have been commercially sexually exploited: Findings from a specialized treatment program. J Child Sex Abus 26(6): 692-709.

- Kasirye R, Lunkuse J (2017) Adolescent girls and young women in rural Uganda; Building resilience among adolescent girls and young women engaging in transactional sex in rural Uganda.

- Katana E, Amodan B O, Bulage L (2021) Violence and discrimination among Ugandan residents during the COVID-19 lockdown. BMC Public Health 21: 467.

- O’Brien J E, White K, Rizo C F (2017) Domestic minor sex trafficking among child welfare-involved youth: An exploratory study of correlates. Child Maltreat 22: 265-274.

- Rukundo G Z, Mpango R S, Ssembajjwe W (2020) Prevalence and risk factors for youth suicidality among perinatally infected youths living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda: the CHAKA study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 14: 41.

- Semugabo C, Nalinya S, Lubega B G, Ndejjo R, Musoke D (2021) Health Risks in Our Environment: Urban Slum Youth’ Perspectives Using Photovoice in Kampala, Uganda. Sustainability 13(1): 248.

- Stockdale M S, O’Connor M, Gutek B A, Geer T (2002) The relationship between prior sexual abuse and reactions to sexual harrassment: Literature review and empirical study. Psychology Public Policy and Law 8: 64-95.

- United Nations (2018) DRUGS AND AGE; Drugs and associated issues among young people and older people.

- United Nations Population Fund-UNFPA (2017) Adolescents and Youth Dashboard-Uganda.

- Van Egmond M, Garnefski N, Jonker D, Kerkhof A (1993) The relationship between sexual abuse and female suicidal behavior. Crisis 14(3): 129-139.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...