Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Review ArticleOpen Access

Urban Form and Human Behavior in Context of Livable Cities and their Public Realms Volume 3 - Issue 4

Tigran H1*, Littke, H2 and Elahe K3

- 1Associate Professor, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden

- 2Senior Researcher and Urban Planner at the Ecology Group Consultancy in Stockholm

- 3Senior Researcher and Urban Designer at Theatrum Mundi Charity in London

Received: January 23, 2020; Published: February 04, 2020

Corresponding author: Tigran Haas, Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Urban Design at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, and Director of the Centre for the Future of Places (CFP) at KTH, Stockholm, Sweden

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2020.03.000167

Introduction

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

In what ways are cities things that happen to us, and in what ways are cities things we do together, with more or less art and purpose? How do we understand both the geometries of cities and the ways that form might be connected-or not-to their social organization and politics? These are some of the reasons and potential lacunas in research which need for a cross-disciplinary approach related to urban form and social behavior and a revamped effort at uniting the disciplines of the built environment and behavioral sciences. The remarkable link between intrinsic human qualities such as behavior, conduct, and demeanor, and the external environment has been recognized for years. However, this link has not been given much consideration in the design of our built environment. This needs to change as architecture, urban planning & design are crucial for achieving true urban sustainability in our cities. Environmental psychology applies social science methods and theories to real world questions about human experience in everyday physical environments. Unlike the normative approach, it seeks to describe the world the way it is-how we use it and, in turn, how it affects our behavior-to build a knowledge base for urban design. Through a multilevel, multidisciplinary, social and spatial environmental approach we will examine relationships between characteristics of the physical environment, humans, context and human responses. It will be an evolving knowledge base for urban design decisions. There are significant reasons why planning and designing the city is so important today, maybe more than ever before. The most crucial one is that current urban development and urban living patterns are characterized by fast flows of capital, media, transport and multitasking. These are time-technology patterns are today regarded by many as ultimately unsustainable because of the destructive burden they place on the environment. One of the causes for this destructive influence is believed to be the contemporary city’s very form and structure, which urgently

requires improvement. This in turn highlights the vital role of urban planning and urban design. It is therefore essential to spell out the significant contribution urban planning and design can and should make towards sustainable urban development and social life by fully understanding the consequences if and improving the city’s form and structure.

The city’s most important advantages are often said to be that it offers choice, an exciting lifestyle; it provides access to services and facilities; it has stimulating features and represents an intellectual challenge; and it offers workplaces. However, all cities are different and some offer their citizens more advantages than do others. It is the main objective of good urban planning and design to create new advantages or enhance the existing advantages a ‘good’ city and ‘good urbanity’ has to offer.

The urban form and human behavior

The Urban Form and Human Behavior research within disciplines of the built environment sets out to investigate and discusses issues of urban form and its connection to social life and human behavior to provide insights and frameworks to support sustainable, livable and flourishing cities. The idea is to revive behavior based urban research, focusing on public space and human well-being arguing for the importance to acknowledging the importance of places over objects, and collaborations between disciplines. There is an intricate link between city structure and the possibilities for public life. As Christopher Alexander pointed out, ‘A Millennia of Research findings’ and evidence-based material that just needs to be excavated and applied in a proper way [1]. The challenge for this field and research is to map and spot as well as study the urban form and content and its connection to social processes; to excavate and sort all the results and findings of previous theoretical and practical work of architects, planners, human geographers, environmental psychologists, ethnologists, ecologists, historians, and others that has relevance in this field.

In urban planning and design research and practice there is a

broad understanding that design of the built environment matters

to the life and well-being of communities and individuals. Opinions

differ markedly, however, on what role such environments play

in influencing behavior, especially as they might contribute to

desirable social ends. While the historian John Archer argued

that architecture and urbanism structure human behavior [2],

Sociologist Herbert Gans believed that architecture and urbanism

cannot solve society and its problems through design [3]. As to find

a balance of those opposing views one must dwell into these issues

of urban form and social life i.e. the well-being of people together

with climate change and energy issues that are on the top of the

agenda. Aside from the fact that human behavior and social life

are part and being shaped by a complex web of other economic,

political, cultural, ethnic and other links and prerequisites, it is hard

not to agree that the built environment plays an important role in

that also. Urban design Professor Chuck Bohl sees this in a way that

design can shape spaces to afford opportunities for positive social

activities, a type of ‘environmental affordance’ [4].

Moving beyond the environmental determinism, i.e. believing

that urban environment decides or changes social behavior, one

cannot avoid not to assert, that if the built environment does not

afford a desirable behavior, the behavior cannot really take place at

all as discussed by [5,6]. Coupled to that, John Archer’s statement

finds even more fertile ground when we look from the other corner

and assert, from the fact that the more processes are understood,

the better the architecture and urbanism can serve human

needs. Form and Behavior; Streets really are for people, not cars,

Copenhagen Denmark (Figure 1) Photo Courtesy of Lloyd Alter.

2:24 PM · Aug 31, 2017 Whether diversity and rich social life thrives

better, or can be sustained longer, under certain physical condition

that planners and urban designers may have some control over is

the first question that might be posed. Asking whether the built

environment and specific urban form creates diversity and social life

would be another. The real art and mystery of scientific discovery,

as well as the absence of falling into the prescribed determinist trap

lies in the former one. These are important questions for architects,

planners and urban designers, researchers and practitioners alike.

As Emily Talen astutely asserts, physical design cannot create sense

of community, but rather, it can increase its probability-something

that argues for environmental probabilism rather than determinism

[7,8]. Spatial arrangement is therefore a medium rather than a

variable with its own effect. There is no doubt that there is a direct

relationship between physical design and social behavior. Just as

there seemed to be deep structures shaping the social patterns

of our cities there seems to be ‘deep structures’ defining the

organization of their built environments. To reach urban design

decisions about the shape and form of different environmental

settings, designers should know about the interaction between

environment and behavior-how variable configurations of the built

environment may influence preferences and behaviors. This is the

focus and realm of environmental psychology. Our research will put

a specific focus (through rigorous explorative research and case

studies) on how our environment affects our behavior.

Figure 1: Form and Behavior; Streets really are for people, not cars, Copenhagen Denmark. Photo Courtesy of Lloyd Alter. 2:24 PM · Aug 31, 2017.

Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

a) Environmental determinism-the environment causes

behavior-e.g. overcrowding causes criminal behavior.

b) Environmental probabilism-the environment is a seen

as a set of opportunities within which choices are made, but

environmental conditions make some choices (and hence

outcomes) more probable than others-e.g. overcrowding makes

criminality more probable rather than causing it.

c) Environmental possibilism-the environment sets limits

upon but doesn’t restrict behavior-e.g. overcrowding makes it

possible that criminality will occur, but humans can also shape

their environment in order to make other things possible, e.g.

more sociable behavior [9-12].

Environmental probabilism is a thought that considers the probabilistic relationship between physical environments and behavior. Although features of the physical environment lend themselves theoretically to all possibilities, the layout, location, and arrangement of space and facilities render some behaviors much more likely, and thus more probable, than others. While Richard Sennett might see urbanity as a setting for human comprehension of social complexity and the development of empathy [13], Henry Lefebvre concerns with urbanity relate to the possibilities of action both through self- expression and more collectively [14,15]. Both see the importance and link between urbanity, urban form and social processes, behavior. Creating an environment where desired forms of behavior (i.e. social life, interaction and sense of community) depend on particular social situations. The relationship between environment and behavior is complex.

A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

For the sheer definition of the concept of urban form, this

research defines urban form as a social multi-element multifunctional

system under the action of city’s own graphic pattern

and form, the layout structure, such as a very specific visual style of

physical performance. Therefore, the study of urban form, including

physical elements and multiple cultural connotations together with

the urban form itself is formed by the accumulation of history, and

has the characteristics of dynamic evolution, which makes urban

form studies to become very rich content of the comprehensive

social content. When looking for the ‘most urban’ or ‘urbane’ in

urban planning and design the notions of density, mixed use, and

increasingly the notion of comes up. However, one can argue that

there is not a real theory, on either the ‘urban’ at large, or ‘urbanity’,

in what is generally considered to be the field of urban design.

The field is often dominated by concerns related to typologies at

different scales [16-19], aesthetics and style, and relations between

form and function that are based on normative processes rather

than research. Urbanity, as the famous sociologist [20,21] would

both agree, but from different perspectives and approaches, that

it has to do with a rudimentary social and cultural playing field

related to urban form, public space, streets, squares and buildings

including environments for strangers and chance. It is in a way a

rich information field between humans and between humans and

artifacts in a freely accessible space but stable place where the new

and unexpected can happen in ever new combinations.

A renewed interest in urbanism can be seen in the popularity

of approaches such as New Urbanism, the compact and mixed used

city and an increase focus on public space. New Urbanism [22-26],

Transit Oriented Development [27,28] and the hegemonic status

of the compact city as a sustainable urban form all expressions of

this renewal. The performability of urban form needs thus to be

researched and in the scope of this research a broad understanding

of urban form is acknowledged. As multi-element multi-functional

system urban forms is discussed through lenses ranging from

urbanization processes to design and management of public space,

but always present as social and physical elements of the city always

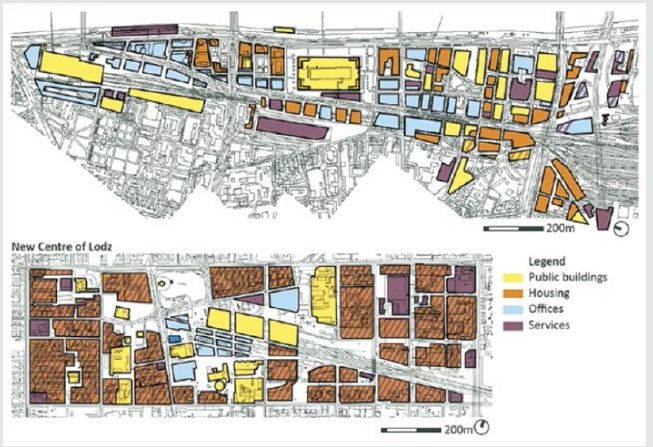

exits, functions and interacts through their relationship (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of the main functions in Paris Rive Gauche and the New Centre of Lodz Source: prepared by the author based on her site studies and data provided by Semapa and the City of Lodz. Kind Permission from Monika Maria Cysek- Pawlak: Urban Development Issues 57, 1; 10.2478/udi-2018-0017.

Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

There is a widespread consensus that progress towards

sustainable development is essential. Human activity cannot

continue to use resources at the present rate without jeopardizing

opportunities for future generations. Cities are the main arena

of human activity, but they are also the greatest consumers of

natural resources. However, urban sustainability is not just about

environmental concerns; it is also about economic viability,

livability and social equity. Recently, much attention has focused

on the relationship between urban form and sustainability, the

suggestion being that the shape and density of cities can have

implications for their future. From this debate, strong arguments

are emerging that the compact city is the most sustainable urban

form. Densification as a term was first used in 1934 as a response

to urban sprawl [29] and in later years when ideas of sustainability

has come to influence the whole urban planning and design

discipline, the compact city has become a central tool to create

sustainable city [30]. In the contemporary debate compactness is

still portrayed as a remedy against sprawl [31-33]. The compact city

shows a great potential for more efficient use of resources by more

efficient land resources, less traffic, and improved social cohesion,

accessibility and walkability but concerns are raised as travel

patterns and lifestyles are not only decided by distance and density

[34,35]. Further the picture is complicated as there are many ways

of measuring compactness. Population density, i.e. inhabitant per

area, is often used but does not say anything about urban form. The

same goes for tools such as ground space index, i.e. built up space

per area, or floor space index, the ration between all built space on

all floors and the total area [36].

Despite these concerns, sustainable compact cities could

reinstate the city as the ideal habitat for a community-based and

social life society. Combining a focus on density and compactness

with traditional inspired cities relating to the human scale and

everyday needs, the compact city can be interpreted in all manner

of ways in response to all manner of cultures. Cities should be about

the people they shelter, about face-to-face contact, about condensing

the ferment of human activity, about generating and expressing

local culture. Form, in and of itself, is not measurable in terms of

sustainability, but it can facilitate more sustainable lifestyles. The

best principle of spatial practice, however, is that the practitioner,

informed by past and current models and practices, engages in

direct observation of and participation in the social behaviors of

people and their environment, because behind all the data and the

success of any given place, lies the perception, behavior, and feeling

of a human being.

The compact, diverse, dense city has potential of fostering

urban communities in social, economic and institutional terms, is

the same city which seems to show the best performances in terms

of energy efficiency and balanced modal split in transportation. As

Porta [37] remarks, ‘components such as “transparency” of street

facades, the number of shop windows and entrances, the need for

many medium or small size buildings, public spaces, the need for

“anchor objects”, the need for integration rather than separation

of different uses and users within the same urban and places and

objects to sit on are important for the investigation of the social

dimension of urban life’. Here the compact city and the traditional

city and street scape become crucial perspectives for an inclusive,

livable and sustainable future city (Figure 3).

Figure 3: London: How can compact cities keep house prices under control? Southwark (left): surprisingly un-dense. Image: Kind Permission to us from Getty.

The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

The social dimension of urban design concerns the relationship between physical space and social activities. It also implies the interrelated notions of public space and public life. It raises difficult questions regarding the effects of design on individuals and social groups. The claim that the physical environment has a determining influence on human behavior is dismissible as environmental determinism. However, as urbanist Peter Calthorpe has argued, ‘it is just as simplistic to claim that the form of communities has no impact on human behavior as it is to claim that we can prescribe behavior by physical design’ Calthrope [38]. In fact, as urban design theory has showed, while design by itself might not be enough to bring about social change, the physical form of urban places does inhibit certain social activities while making others possible [39-41]. Concurrently, the understanding of public space as the network of sites and settings of public life entails the notion that public spaces must ideally function as a forum for political action and representation; as a “neutral” or common ground for social interaction; and as a stage for social learning, personal development, and information exchange [42-46]. The important thing to keep in mind and to understand is that public space is not only made of streets, squares and public open spaces but also of a series of “third places”-in contrast to the home as first and workplaces as second - such as sidewalk cafes, pubs, bookstores, post offices, restaurants and corner stores that make up a set of informal sociocultural transaction [47]. The ability of the built environment to provide such informal “third places” is thus a significant feature of good urban design and point to a direct relation of urban form and social life. As Nan Ellan, renowned urban theorist and Professor of Architecture, points out, public life is increasingly thriving in other types of places such as shopping malls and theme parks that are places of consumption and private interests Ellin [48]. Despite their popularity, these privately managed and controlled environments lack many of the defining characteristics of urbanity and of truly public spaces of encounter, and as Richard Sennett observes their proliferation raises serious questions regarding the privatization of the public realm and the threat of the “end of public culture” (1992) or as geographer Don Mitchell puts it “end of public space” (1995) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Coworkers, Taipei, Taipei 101, Taipei Central iconic green promenade and skyline. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Liu, | AFP | Getty Images.

Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

For the study of social dimensions several conceptual and theoretical approaches and perspectives can be used. Architect Amos Rapaport has demonstrated the role of social and cultural factors in shaping traditional houses Rapaport [49] and architectural and forensic psychologist David Canter has studied the interactions between people and buildings, providing evidence based design on the designs of offices, schools, prisons, housing and other building forms as well as exploring how people made sense of the large scale environment, notably cities [50]. Environmental psychology is an interdisciplinary field focused on analyzing “the transactions and interrelationships of human experiences and actions with pertinent aspects of the socio-physical surroundings” [51]. The field defines the term environment broadly, encompassing natural environments, social settings, built environments, learning environments, and informational environments and investigate areas such as common property resource management, wayfinding, the effect of environmental stress on human performance, the characteristics of restorative environments, human information processing, and the promotion of durable conservation behavior. In recent years an increased focus on climate change and sustainability these issues have been increasingly in focus also within environmental psychology [52].

Important urbanism researcher such as Emily Talen, David Canter and Jack Nasar have noted and observed, that it is crucial and highly beneficial to stop ignoring the contributions of each field from the other as we are then missing out on a potentially important and extremely rich opportunity to make a difference in the real world of planning and designing, as well as repairing and retrofitting our cities [53-56]. urban planning and urban design are inter- and multidisciplinary endeavors that are open to social science and social science methods. As academic and professional disciplines the focus is on the interrelationships between all the different aspects of the environment. For example, mutual dependencies between the housing, service, and employment systems and the transportation system that links them, no one system can be planned separately without considering its relationship with the others. This is, of course, not to say that this ideal is achieved in every case, but it is recognized as an ideal. Environmental psychologist Roger Barker developed the concept of the behavior setting to help explain the interplay between the individual and the immediate environment [57]. The power of a behavior setting emanates from several sources. The most important of these is the extra individual nature of the behavior setting; that is, according to Roger Barker the behavioral setting exists independent on one’s perception of its Baker [58]. The behavior setting is an objective, naturally occurring phenomenon with a specified time-space locus occurring outside the individual. People enter the setting by choice, but once in the setting, they usually conform to its constraints.

“It is the setting itself that directs their molar behavior, not the individual personalities (or other individual differences) of the inhabitants. Settings do, of course, change over time, and participants play roles in these changes. A second source of power of a behavior setting occurs as a function of the fact that all the setting components have a stronger degree of interdependence among themselves than they do with components outside the setting. Barker talked about the various elements in a behavior setting being synomorphic (having a similar form) and the physical environment being circumjacent to (surrounding) the behavior” [59]. Edward T Hall, a leading anthropologist and cross-cultural researcher, on the other hand created the concept of proxemics (Hall, 1990). Proxemics is the study of set measurable distances between people as they interact. Edward Hall described the subjective dimensions that surround each of us and the physical distances one tries to keep from other people, according to subtle cultural rules. So, given this outstanding variety, richness of findings and the incredible dynamics penetrating the urban planning and design field, one of the fundamental issues afore us, is a need to start a research-dialogue about the present and future of social research in urban planning and environmental design.

Even though “the social” is still a major concern in urban planning and design research today, other fields also have staked a claim to the analysis of social issues related to space. We have to ask how contemporary research addresses the idea of “the social” in space, not only from those in our urban planning and design field, but also from those in emerging fields of research, to understand how we might address critiques such as the disconnect with design practice and our use of social science methods. Thus, one of the objectives is to connect researchers across dispersed fields, excavate the findings lost in time and forgotten by our professions and to provide a new cross-disciplinary platform for working together to define a common set of interests, research questions, and set a new direction for our field. In short, research needs to seek the rebirth and redefinition of social factors (life and behavior) within the urban form (Figure 5).

Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

Urban design is not just about transforming spatial arrangements, but it is also about the aspects of dealing with use and management of those environments and the social flows and linkages that this synergy produces. Urban design theorist and architect professor Ali Madanipour has viewed this in the sense that there are more deeply seated social and cultural relations between society and space that urban design addresses at the current and that it should address [60]. Social and spatial (physical) are intertwined in our understanding of urban space. The same applies to the transformation of any urban space in our cities. When we are engaged in shaping the urban space, we are inevitably dealing with its social content. The modernist design had the ambition of changing societies through space. This was a mechanistic view of how society and space are interrelated, which became known as environmental determinism and social engineering. This crude view is now widely discarded [61]. It’s obvious that is that there is a strong interaction and co-relation between place, space (i.e. urban form) and the social processes (i.e. behavior). There are, however, professionals and theorist who see urban design as merely spatial involvement without a social dimension [62]. This is particularly the case when the visual element(s) of urban design work are more emphasized. Therefore, the spatial transformation can be both caused by and causing social change. Ali Madanipour sees this happening at a variety of scales and degrees of impact. For him the correlation is inevitable. This is especially felt when aspects of urban design such as the management of urban environments or change in land use are dealt with [63].

The way society and space are interrelated is a main concern of urban design education. Urban design deals with the complexity of the interrelationship between buildings and the streets, squares, parks and other open public spaces which make up the public realm, i.e. the complex interrelationship between all the various elements of built and unbuilt space, and those responsible for them. Urban design and planning can therefore be seen as the sociospatial management of the urban environment using both visual and verbal means of communication and engaging in a variety of scales of urban socio-spatial complex phenomena. Already in the 1960’s, a person of unprecedented erudition and what most of the professional community regards as one of the most influential urbanists of our time, Jane Jacobs emphasized the complexity of cities and the linkages of form and life in her widely red and cited book ‘Life and Death of the Great American City’ [64].

She described cities to be problems in organized complexity and that they present situations in which half-dozen quantities are all varying simultaneously and in subtly interconnected ways, physical and social. Cities do not exhibit one problem in organized complexity, which if understood explains all. They can be analyzed into many such problems or segments which are also related with one another. Jane Jacobs also posted a number of timeless principles and well argument examples of good urbanism. She also selected the four major aspects for cities to be cities for people and cities that are created from good neighborhoods that allow urban form and social life to flourish as one: that cities have enough density, that blocks are short to permit urban street life, mixture by old and new to elevate the historical aspects of the neighborhood and lastly a mix of functions throughout the city [65]. She also emphasized, as did the leading expert on Streets and Boulevards [66], that there really is no perfect form of street fabric-many different networks and patterns are capable of producing wonderful places and being friendly for pedestrians as long as their fabric allows frequent and comprehensive linkages and scales that work – there simply seems to be an upper scale beyond which all hope of efficient (and therefore popular) pedestrian circulation and real social life is gone.

Focusing on Public Spaces

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

At the core of urbanity and the focus of urbanism lies public

space. Great architecture can be expressed though the individual

building, but their context, cohesion and connection builds up the

city. It’s the ‘life between the buildings’ to paraphrase Jan Gehl [67],

The Danish Architectural Press) that is the city-and thus the realm

of urbanism and urban design. When late-modern functionalists

spread dwellings out for increased light and ventilation, and

separated uses Le Corbusier [68], they also thinned out people

and events. Observations of social behavior in space, such as

those conducted by Gehl, indicate that increased spatial distance

increases social distance. While social interaction cannot be

enforced by physical design, it can be encouraged (or discouraged)

by it. In contemporary urbanism debates on the nature of public

space as well as how to conceptualize publicness are raging and

are therefore important discussions within the Urban Form and

Human Behavior realm.

For example, what makes a great public space? There are

numerous spatial and social qualities involved, of course: Issue

of size, scale, degree of physical enclosure, amenities, aesthetics,

and other variables matter; public spaces at different times and in

dissimilar contexts might change in their role of accommodating

various and heterogeneous groups of people in the city [69]. These

changing roles also mean changing conditions for various social and

economic groups, for those inhabiting the adjacent urban realms,

and for those visiting or passing by [70-75]. This urban complexity

clearly demonstrates the complexity of the problem of public space

and begins to point toward a new nomenclature.

Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

The public realm of a city consists of a wide range of spatial concepts including squares, streets, parks, in-between-places, third places and virtual places. For the study of human behavior all these places are central. Traditional conceptions of public spaces have focused on the square, the forum or agora, but in the contemporary city a multitude of public spaces and multiply publics must be acknowledged. An important concept in understanding urban form, social life and importance of place lies in the concept of third place [76,77]. These places are different from primary and secondary places of home and work. This is a place where the community feeling is being developed and nurtured. Third places are gathering places and their importance is in nourishing sociability. For these places to work, they need to fully enable a culture of social inclusion, multiculturalism, ethnic diversity and a balance social mix, instead of becoming very segregated, mono cultural realms. Third places such as coffee houses, community centers, groceries, markets, bazaars, parks, discussion rooms, etc. are of extreme importance for a vibrant life of any neighborhood, town or city. Oldenburg [78] describes these places as social condensers arguing that a wellfunctioning public realm with a richness of third place can build social capital by enforcing and melding social relations.

Third places are crucial to a community for a number of reasons. They are firstly distinctive informal gathering places, secondly, they make the citizen feel at home and thirdly they nourish relationships and a diversity of human contact. They help create a sense of place and community and finally they invoke a sense of civic pride. The key ingredient lies in the fact that they are socially binding, encouraging sociability at the same time and fighting against physical and human isolation- facilitators of vibrant and good public life and that in most cases they are in synergy with open public spaces, like squares, bazaars and other markets. Oldenburg points at the essential ingredients for a well-functioning third place: that they are free or relatively inexpensive to enter, that they are highly accessible, number of people can be expected to be there on a daily basis and all people should feel welcome, regardless of their race, gender or religion [79].

Further, social life in the 21st century is increasingly becoming a life lived in media cities. This statement suggests two things simultaneously. First, that the spaces and rhythms of contemporary cities are radically different to those described in classic theories of urbanism; and second, as much as the city has changed, so have media. What emerges as an interesting conundrum is the relationship between the physical sociability, privatization of public space, inter-personal alienation, transformation of classical spaces and new human-computer interaction [80], one of the virtual reality and internet pioneers and founders duly notes that the whole point was to make the internet and the world wide web as a more creative, expressive, empathetic, and interesting world. This can be linked to the notion and representation of the ‘3rd place’ concept discussed above; related to the notion of third places, I places would be a new kind of fourth place that is built around virtual social webs and online networking but still grounded in physical (social) presence and in proximity of easy consumption that can be found in a renewed third place setting.

Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

Seminal work to investigate use and behavior in public spaces has been carried out by Danish architect Jan Gehl. Among his many publications Life between Buildings [81] and latest Cities for People (2013) are worth pointing out where he discusses necessary activities, optional activities and social activities in public spaces. While necessary activities take place regardless of the quality of the physical environment, optional activities depend to a significant degree on what the place has to offer and how it makes people behave and feel about it. The better a place, the more optional activity occurs and the longer necessary activity lasts. Social activity is the fruit of the quality and length of the other types of activities, because it occurs spontaneously when people meet in a particular place. Social activities include children’s play, greetings and conversations, communal activities of various kinds, and simply seeing and hearing other people. Communal spaces in cities and residential areas become meaningful and attractive when all activities of all types occur in combination and feed off each other. Using the term “social capital” sociologist and Harvard Professor Robert Putnam describes successful communities in which gathering places are essential to build social capital through informal contacts, respite from home and work and nurturing social interactions. In particular, walkable streets are emphasized as the physical basis of community [82].

William H. Whyte investigates a similar notion of the edge effect in The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces [83], Project for Public Space). He, as did Jan Gehl, focused on the public space between buildings and its importance to the formation of social relationship. As an urban anthropologist, he used the basic methodology of observing the behavior of people using urban public spaces. In his research of these spaces, he used quantitative time-motion studies to gather data which contributed to new zoning codes for public plazas in the city of New York. What he found was that sun, aesthetics, and the amount of open space were not the primary drivers in plaza use. What was critical was the amount of settable space. Through time lapse photography generating sets of data, Whyte discusses sitting amounts, sitting heights, and tries to find what the best social generator is. In searching for how to make public space more effective he uses a very conversational analysis and storytelling presentation style, mixing quantitative data and adaptive hypotheses. In a time before large quantities of data or the computing power to analyze were available, these two urban taxonomists have defined research methods and means of documentation. They both used firsthand observations and measurements to postulate the most effective urban and orarchitectural interface.

On the analytical side we have the UK planner, geographer and mathematician Professor Bill Hiller and American Spatial Planner and Professor at MIT Kevin Lynch [84]. Developed by Hillier and Hanson [85] space syntax is a set of theories and techniques for the analysis of spatial configurations based on the idea that spaces can be broken down into component and analyzed as networks of choices. Space syntax then enable presentation of these networks as maps and graphs describing the relative connectivity and integration. Integration, Choice and Depth Distance are three basic conceptions and from these components it is thought to be possible to quantify and describe how easily navigable any space is. Space syntax is nowadays a tool used around the world in a variety of research areas and design applications including architecture, urban design, planning, transport and interior design. Kevin Lynch, a MIT Professor of Spatial and Urban Planning, has provided seminal contributions to the field of city planning through empirical research on how individuals perceive and navigate the urban landscape. His books explore the presence of time and history in the urban environment, how urban environments affect children, and how to harness human perception of the physical form of cities and regions as the conceptual basis for good urban design. Lynch’s most famous work, The Image of the City published in 1960, is the result of a five-year study on how users perceive and organize spatial information as they navigate through cities

Using three disparate cities as examples (Boston, Jersey City, and Los Angeles), Lynch reported that users understood their surroundings in consistent and predictable ways, forming mental maps with five elements: paths, the streets, sidewalks, trails, and other channels in which people travel; edges, perceived boundaries such as walls, buildings, and shorelines; districts, relatively large sections of the city distinguished by some identity or character; nodes, focal points, intersections or loci; landmarks, readily identifiable objects which serve as external reference points. In the same book Lynch also coined the words “imageability” and “wayfinding”. Image of the City has had important and durable influence in the fields of urban planning and environmental psychology and shows direct correlation between urban form and social behavior, as does the work of Bill Hillier. Many common principles of working with urban form to increase social interaction and social life have been proposed. Human scale, densities, pedestrian orientation, 500m walking radius, gathering places, center and edge conditions, codes for spatial arrangements such as setbacks, lot sizes, buildings heights, height- to-width ratios, street widths and parking, sidewalk widths and distances, hierarchies of streets, and so forth have been described by all of these authors to varying degree, from generic principles to highly detailed and specific codes of design for an entire lexicon of public spaces. The important thing to note is that a wide variety of practitioners have reached remarkably similar conclusions on basic principles of spatial design using different methods from different disciplines but still all within urban planning and urban design.

Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

As Haas and Eligo argue, “the ability to reduce the city to an object of technical expertise was the dream of the Progressive Era reforms ranging from changes in city government to the professionalization of city planning as part of city management” (2014: 20). Central in Jane Jacobs’ critique of the urban planning and design professions was not specifically that they had developed bad solutions, but that they had been asking the wrong kinds of questions working with models and analogies from the wrong sciences [86]. Critical dimensions of equity, diversity, and democracy are crucial to get us closer to something what might become a just city [87]. Although architecture and urban planning and design have in recent years has turned away from the pragmatic social and behavioral sciences to the wilder reaches of critical theory [88-90] the task of theory is to aid in the kind of critical reflection that can help us be precise about the questions we ask. Questions and projects in urban planning and design are always embedded in the physical world thus making relationships to the physical, the concept of place, elementary.

In the age of globalization, places are important bases for identity building for several reasons that change in accordance to the dimension of place. The small places are important for people that concretely use the resources they offer and develop inside the territory their social network. This importance could foster a positive identification with the place. As place dimension grows, the importance of real characteristics and of a direct contact decreases but places could become the base for relevant social categorization processes for less concrete reasons. These considerations suggest exercising some caution when choosing which spatial range taken into account in research and intervention, since the psychological processes that are connected to place identification can highly differ according to the considered territorial area (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Revitalize Public Spaces: The Seaside Balconies / Pseudonyme. Image courtesy of Edouard Sanville.

The task to understand our relationship to place has compelled many researchers. Donald Appleyard (1981) studied perceptions, attitudes and meanings towards and of place [91,92] dynamics of places central to planning and design. Seminal work was carried out by geographer [93] in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience and environmental psychologist including [94-96] have studied place as critical part of lived experiences. Theory on place includes place attachment [97-100] and place identity [101,102]. These concepts help us understand use and preference of places in turn related to concepts such as social capital, community development and neighborhood revitalization [103,104].

Places always affected human activities providing resources and setting limits, but also had psychological impact provoking relevant feelings and furnishing a base for cognitive elaboration. Environmental Psychology studied the emotional impact of places using the concept of place attachment and its cognitive implications by means of place identity. The complexity of space and place issues, within current urban planning and design discourse sets itself as an important nexus between the physical and social aspects of urban form and there is a need to understand better the intricate relation between space and place. As the famous Norwegian Architect and Phenomenologist Christian Norberg-Schulz observes that we can look at space as an overall system of places (1979). Hence, places are aggregates of permanent features connected by causal relations that are independent of the subject and are arranged in space and time. Following Yi-Fu Tuan, we accept the idea that space is movement and place is a residuum and a comfort of local and anchored malleability (1974). Place becomes synonymous with identification and is an ordering of understanding and experience. Spaces are scenes of existence, and just seem to be simple divisions between our ambience surroundings, between the places we created. Places become an ambient of collective memory (history, culture, personality) and dynamical interaction (people and processes) where spatial, social and psychological (cognitive) aspects play a pivotal role in shaping and assembling something that becomes a place.

Spaces and places are created just as much by social relations and actions as by physical structures. It is suggested that these complex theoretical concepts and tensions among them, have become confused, and that sense of place and place attachment from the experiences of those using places rather than from deliberate ‘place making’. Sense of place is then that something, which we create over the course of time. Kevin Lynch correlates sense of place with identity where that sense of place is the extent to which an individual person can discern or recall a place as being distinct from other places and possesses a character of its own, an attribute closely knitted to the feeling of identity.

Concerning the theory of place three key aspects of place are fundamental to identity, attachment and sense; namely, physical (form and space), functional (activities) and psychological (emotion/cognition; meanings we attribute to places) [11]. Identity and the sense of place in any town or city represent a specific and concrete segment of the spatial continuum filled with meaning and history. A sense of place entails both a positive affirmation of identity and a regressive closure to what lies beyond the divide of the known and unknown (the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’). Space becomes a place when community, its individuals and all people who give form, name and history to space, seize upon its abstract and openended formlessness. Place is a historically relative human creation that defines itself against an alien exterior space: transformation, nature, foreign culture or something else unknown.

In Edward Relph’s thinking, identity of place takes an important role as we must then admit identification with place (1976). It makes a twofold understanding and acceptance in the belief of a power of place; firstly places are those anchors defined by unique locations, landscapes, and communities inhabiting them as well the histories and narratives accumulated there; which directly links to the second issue, that those same communities and people inhabiting those places must concentrate their experiences, intentions, everyday modes of habitual existence onto particular localized settings -on places. When those two strands meet and merge, we become to encounter places of identity and spatial continuum. David Canter further exploring his earlier models, proposed four aspects of place: functional differentiation, place objectives, scale of interaction and aspects of design (1977). An extremely important variable has to be added, namely one of ‘climate’, nested in all places; not only constituting objectively a place but also subjectively influencing the way people experience and remember a place [45]. Place is a complex compound of actions, conceptions and the physical environment. Canter’s visualization of placeness formed when actions, conceptions and physical attributes were inter-related [67]. So, the dialectic relation between space and place manifests itself with particular intensity in towns and cities where in the past it was meaningful to describe the human everyday environment in terms of stable places, such as marketplaces, workplaces, transportation nodes, neighborhoods, or houses. But as William J Mitchell observed, we live in a different world now, a world permeated by digital technologies and transport infrastructures where ubiquitous information, mobility and access to a range of intangible products are essential (2000). In a more mobile life, we tend to free ourselves from the more stable-immobile structures. Simultaneously in those cases there is a tendency towards a loss of attachment to place. Even in a globalizing mobile world a sense of place is of real importance in people’s daily lives because it furnishes the basis of our sense of identity as human beings Over the years, there has been a split of sorts amongst urban planners and designers over what constitutes urban quality or the sense of place. There were those such as Gordon Cullen, architect and urban designer who was a key motivator in the Townscape movement, who place greatest emphasis on physicalitydesign styles, ornamentation and featuring, the way buildings open out into spaces, gateways, vistas, landmarks and the like [23].

This is the rational objective classical view of urban design. Others such as Christopher Alexander or Kevin Lynch stress the psychology of place, bound up in the notion of ‘mental maps’ which people use as internal guides to urban places [15,16]. In doing so, they rely on their senses to tell them whether a place feels safe, comfortable, vibrant, quiet or threatening. If we were to combine these approaches, we would see that urban quality must be considered in much wider terms than the physical attributes of buildings, spaces and street patterns. To be sure, there are many physical elements which, if combined properly (with each other and with the psychology of place) produce urban quality: architectural form, scale, landmarks, vistas, meeting places, open space, greening and so on. Yet the notion of urban quality is clearly more importantly bound up in the social, psychological and cultural dimensions of place. Few theorists have managed to bridge this divide, and most remain either predominantly physical determinists or subjective mental mappers. In the Urban Form and Human Behavior realm the importance of place-based approaches and understanding is deemed critical. As places are incubators of attachment, community development and social capital, acknowledging the importance of place and investigating incentives of place making are central aspects of the research agenda.

Framing a research agenda

Based on the all said above and the study of interlinkages between urban form and human behavior, conducting research work has to be interdisciplinary to synthesize the findings of various research elements, theories and approaches of behavioral sciences and built environment disciplines within the framework to propose tools and measures the research agenda is developed. Criteria for such an endeavor is thus identified as:

Case study research with a strong emphasis on primary data collection

As the research framework argue for local sensitivity as well as creativity and innovation as the aim is to rethink built environment practice and education, case study investigations and primary data is strongly emphasized. Places are individual conditions and networks at the same time, and by adding up case studies both the specific and general can be discussed and scrutinized as case studies include both the exceptional case illuminating the specific and the mundane case embodying the general.

Acknowledging the interconnectedness between place and process

As cities, societies and places are constantly changing and adapting to change, place and process are inherently linked. The urban planning and design process contain constant struggle and negotiation of perspectives, politics and ideals therefore both the physical representation of these in the design and how design informs processes are deemed equally important.

An interdisciplinary approach

Aiming to strengthen the connection between urban planning and design and related fields such as environmental psychology, sociology, and anthropology the research framework focuses on inter- and transdisciplinary approaches. To strengthen understandings of the relationships between urban forms and social dimensions behavioral, psychological and emotional aspects of human interaction with places needs to be of central concern. Ontological and methodological diversity for interdisciplinary explorations are seen as strength of the approach but needs to be sufficiently clarified and discussed.

Multilevel Investigations

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

Connections between urban form and human behavior can be investigated on the local, regional and global scale depending on approach and methodology for the study at hand. Therefore, is multilevel research encouraged within the research framework. Global processes such as urbanization and globalization will in turn have material effects on the local level, and local ideas and practices can influence cultural norms and societal processes.

Present recommendations for policy and practice

Connected to the aim of the research framework all individual projects and case studies done within urban form and human behavior that is built environment disciplines and behavioral sciences should identify recommendations for policy and practice. Contributions span from theoretical explorations, empirical findings and conceptual models.

Research Methodology

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

Urban planning and design as academic and professional fields explores several aspects of the built and social environments of cities and communities, anticipating how the city will function and how it will look as it develops, and redevelops, in the future. Urban planning aspects take into consideration the technical and political process concerned with the welfare of people, control of the use of land, transportation and communication networks, and protection and enhancement of the city environment. The urban design aspects respond to the changes of the technology as well as construction that deal with the look and aesthetic details of urban places and spaces. These designed spaces create a sense of place, character and give meaning to the city as well as become the platform for social interactions that enriches the quality of life for the people, vital not only for the growth of the nation, but also in making a livable and sustainable nation, city, town and neighborhood. The Urban Form and Human Behavior research is structured around an investigation of transforming urban conditions. Within the framework of the research different cases and projects relate to local conditions as well as global phenomena and data collection is carried out at the micro, meso and macro level.

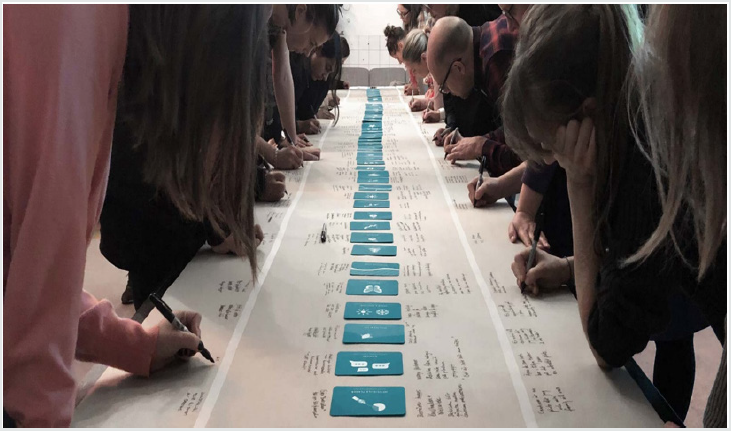

The research engages the advanced study of the fundamental historical understanding of urbanism and how the theoretical and informed knowledge of looking at the city may help advance, and what relevance it has for effective and sensitive urban planning and design interventions in space, in order to create better contemporary places. Central is a qualitative case study methodology acknowledging the importance of primary data collection though interviews, observation, questioners and other methods. A rigid, holistic and systems-oriented methodology using and combining a progressive approach of advanced grounded theory with explorative research, introspection and in-depth literature is deemed important. Causal or predictive approaches in this research seeks to explain what is happening in a particular situation. It aims to generalize from an analysis by predicting certain phenomena on the basis of hypothesized/assertive general relationships. The body of work generated in the research on urban for and human behavior will build up a greater understanding of context sensitive urbanism, globally influential urban strategies, and the multiple dimensions of urban planning and design (Figure 7).

Figure 7: MethodKit for Cities: Defining the building blocks of cities to better discuss them together. Photo Courtesy of Ola Möller (Founder of MethodKit) & Jordan Lane (Architect MSA), co-authors of MethodKit for Cities. May, 5th, 2016.

Conclusion

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

A conceptual toolkit to foster a better understanding of the linkages between urban form and human behavior needs to be developed in various research projects. So far we can see some reoccurring themes for the design and management of successful public spaces including physical features such as urban furnishing and functionality of urban green space including participation, collaboration and integration. From the different research conducted in the field, central findings need to support vibrant and sustainable public spaces and include on a general level the following:

a) Crucial tools for municipalities wanting to promote

a vibrant public space are participation, collaboration and

integration.

b) Public space in the role of a meeting place is important for

integration.

c) Public spaces need social and physical diversity and

openness to local needs as expressed by the social and cultural

context to be successful.

d) Sensitivity to the local context is always important for

urban renewal and transformations.

e) Market driven processes sometimes lack spaces of

engagement for social life improvements putting pressure on

governmental resources.

While on the local level the following

a) Diversity in public space in the form of streets includes

diversity of transport modes, especially with focus on the

pedestrian.

b) Movement patterns, furniture as well as the urban context

influences place expectations and perceptions.

c) Civic involvement in the built environment has the

potential to create a strong sense of attachment.

d) To evaluate sociability of places is an important tool to

create successful urban design.

e) For social media uses in public space both infrastructure

such as WIFI and charging stations are needed as well as a

design to enable behavior connected to social media use.

f) To plan for specific groups such as the elderly population

it is important to acknowledge the complexity and diversity of

these groups.

g) When cities focus on mega event for branding and social

sustainability it is crucial to understands effects of exclusiveness

and exclusion manifested in the public space.

The cities, town, neighborhoods and districts that will do best in the long run will be those that best support an open, equitable public realm, and leverage its benefits for all the people who utilize those places. This is because, as we see in this issue of human behavior and urban form research, public spaces that can offer the capacity to support a complex agenda of livability and sociability, economic prosperity, community cohesion, social justice, and overall sustainability for cities. Yet as we also learn from the authors herein, these goals can only be achieved if we understand, and assure, the fully open, porous and dynamic nature of public spaces-which is, in fact, the very essence of their publicness.

References

- Introduction

- Arguments Center on How Much the Environment Determines our Behavior

- A Renewed Interest in Urbanism

- Compact Cities: Traditional and Contemporary

- The Social Environmental Dimensions

- Learning from Environmental Psychology

- Urban Design as Social and Physical Realm

- Focusing on Public Spaces

- Multiplicity of the Public Realm

- Use and Behavior of the Public Space

- Acknowledging the Importance of Place

- Multilevel Investigations

- Research Methodology

- Conclusion

- Introduction

- Alexander C (1977) A Pattern Language. Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Alexander C (1979) The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Alexander C (1987) A New Theory of Urban Design. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Alexander Christopher (1965) A City is not a tree. Published in two consecutive issues of Architectural Forum 122(1): 58-62.

- Alexander Christopher (1987) A new theory of urban design. Oxford University Press, United States.

- Alexander Christopher (2002) The nature of order. Oxford University Press, New York, United States.

- Altman Irwin (1986) Theoretical issues in environmental psychology. Paper presented at the 21st IAAP Congress, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Amin Ash (2008) Collective Culture and Urban Public Space. City Journal (Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action) Routledge 12(1): 5-24.

- Appleyard D (1981) Liveable Streets, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- Archer John (2008) Architecture and Suburbia. From English Villa to American Dream House, 1690-2000. University of Minnesota. Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Arefi M, Triantafillou M (2005) Reflections on the pedagogy of place in planning and urban design. Journal of planning education and research 25(1):75-88.

- AyichewFekaduKassa (2014) The paradox in environmental determinism and possibilism. A literature review. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 7(7): 132-139.

- Barker RG (1968) Ecological Psychology. Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA.

- Baum A, Paulus PB (1987) Crowding. In. Stokols D, Altman I (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (1:533-570). New York. Academic Press, UK.

- Berghauser Pont, Metaoch Haupt Per (2005) The Spacemate. Density and the typhomorpholgy of the urban fabric. Nordisk Arkitekturforskning.

- Bohl C (2002) Place Making. Developing Town Centers, Main Streets, and Urban Villages. Urban Land Institute Press, Washington DC, USA.

- Bohl Charles C (2001) New Urbanism and the City. Potential Implications and Applications for Distressed Inner-City Neighborhoods. Housing Policy Debate 11(4): 761-801.

- Bohl Charles C (2003) The Return of the Town Center. Wharton Real Estate Review 7(1): 54-70.

- Bohl Charles C (2003) To What Extent and in What Ways Should Governmental Bodies Regulate Urban Planning? Journal of Markets and Morality 6(1): 1-50.

- Bohl Charles C, Elizabeth Plater Zyberk (2006) Building Community Across the Rural-to-Urban Transect. Places 18(1): 4-17.

- Burgess R (2002) The Compact City Debate. A Global Perspective. In. Burgess R, Ajenks M (Eds.), Compact Cities. Sustainable Urban Forms for Developing Countries, Spon Press, London, p. 9-24.

- Calthorpe P (1993) The next American metropolis. ecology, community, and the American dream, Princeton Architectural Press, London, USA.

- Canter DV, Craik KH (1981) Environmental psychology. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1(1): 1-11.

- Canter David V (1977) Psychology of Place. Architectural Press, London, USA.

- Canter David (1997) The Facets of Place. In. Advances in Environment, Behavior and Design, Gary T Moore, Robert W Marans (Eds.), Toward the Integration of Theory, Methods, Research, and Utilization, New York pp. 109-148.

- Carmona M, Heath TOC, Tiesdell S (2003) Public Places-Urban Space. The Dimensions of Urban Design. The Architectural Press,Oxford, USA.

- Carmona M, Tiesdell S (2007) Urban design reader. Routledge, Oxford.

- Cullen G (1961) The concise townscape. Routledge.

- De Young R (2013) Environmental Psychology Overview. Ann H. Huffman & Stephanie Klein (Edt.), Green Organizations. Driving Change with IO Psychology,Routledge, New York,p. 17-33.

- Dieleman F, Wegener M (2004) Compact City and Urban Sprawl. Built Environment 30(4). 308-323.

- Dittmar H, Ohland G (2012) The new transit town. best practices in transit-oriented development. Island Press, USA.

- Ejigu AG, Haas T (2014) Sustainable Urbanism. Moving Past Neo Modernist and Neo Traditionalist Housing Strategies. Open House International 39(1): 24-150.

- Ellin N (1997) Architecture of fear. Princeton Architectural Press. New York, USA.

- Fainstein SS, Servon LJ (2005) Gender and planning. A reader. Rutgers University Press. New Brunsvik, USA.

- Frank LD, Engelke PO (2001) The built environment and human activity patterns. exploring the impacts of urban form on public health. Journal of Planning Literature 16(2): 202-218.

- Gans H (1982) Urban Villagers. Group and Class in the Life of Italian Americans. The Free Press (Macmillan Co. Inc.) New York, USA.

- Gans Herbert J (1967) The Levittowners. Pantheon, New York, USA.

- Gans Herbert J (1968) People and Plans. Essays on Urban Problems and Solutions. New York, USA.

- Gans Herbert J (1991) People, Plans, and Policies. Essays on Poverty, Racism, and Other National Urban Problems. Columbia University Press, New York, USA.

- Gans Herbert (1962) The Urban Villagers. Free Press, New York, USA.

- Gehl J (1987) Life Between Buildings Using Public Space. 6th(edn.), The Danish Architectural Press, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Gehl J, Gemzøe L (1996) Public Spaces Public Life. The Danish Architectural Press, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Gehl J, Gemzøe L (2000) New City Spaces, The Danish Architectural Press, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Gehl J, Gemzoe L, Kirknaes S, Søndergaard BS (2006) New City Life, The Danish Architectural Press, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Gibson JJ (1966) The senses considered as perceptual systems. Oxford, Houghton Mifflin, England.

- Goonewardena K, Kipfer S, Milgrom R, Schmid C (2008) Space, difference, everyday life. reading Henri Lefebvre, Routledge, London.

- Haas Tigran (2008) New Urbanism & Beyond. Designing Cities for the Future. Rizzoli. New York, USA.

- Haas T, Olsson K (2014) Transmutation and Reinvention of Public Spaces Through Ideals of Urban Planning and Design. Space and Culture Journal 17(1): 59-68.

- Haferkamp H, Smelser NJ (1992) Social change and modernity. University of California press, Berkeley, US.

- Hall Edward (1990) The Hidden Dimensions. Anchor Books. New York, USA.

- Hofstad H (2012) Compact City Development. High Ideals and Emerging Practices. European Journal of Spatial Development (49): 1-23.

- Jacobs Alan B (1993) Great Streets. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Jacobs J (1961) Life and Death of the Great American City. Randome house. London.

- James Howard Kunstler (1994) The Geography of Nowhere. The Rise and Decline of America's Man-Made Landscape. New York. Free Press, USA.

- James Howard Kunstler (1998) Home from Nowhere. Remaking Our Everyday World for the 21st Century, First Touchstone Edition, London.

- Katz P (1994) The new urbanism. Toward an Architecture of community. McGraw-Hill, New York, UK.

- Kelbaugh D (2008) Toward Neighborhood and Regional Design. Pioneer America Society Transactions. PAST p. 31-77.

- Kelbaugh D, McCullough K (2008) Writing urbanism. a design reader. Routledge, London.

- Knez I (2005) Attachment and identity as related to a place and its perceived climate. Journal of environmental psychology 25(2): 207-218.

- Krenz A (2002) Compact City, Theory and Reality. Proceedings of The PLEA 2002 Conference Design With The Environment, Toulouse pp. 613-618.

- Lang JT (2005) Urban design. a typology of procedures and products. Elsevier. Oxford, UK.

- Lang Jon (1987) Creating Architectural Theory. The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental Design. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

- Lanier J (2010) You Are Not a Gadget. A Manifesto. Alfred A Knopf, New York, USA.

- Leccese M, McCormick K (2000) The Charter of the New Urbanism. New York. McGraw Hill, USA.

- Lefebvre H (1992) Production of Space. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, USA.

- Lefebvre H (1996) Writings on Cities. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, UK.

- Lefebvre H (2003) The Urban Revolution. University of Minnesota Press, US.

- Lewicka Maria (2011) Place attachment. How far have we come in the last 40 years?. Journal of Environmental Psychology 31(3): 207-230.

- Low SM, Altman I (1992) Place attachment. In Place attachment, Springer, USA, p. 1-12.

- Lynch K (1960) The Image of the City. MIT Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Lynch K (1981) Good city form. MIT Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Madanipour A (1997) Ambiguities of urban design. The Town Planning Review 68(3):363-383.

- Madanipour A (2014) Urban design space and society. Palgrave Macmillian, London, UK.

- Madanipour A (2013) Whose public space? International case studies in urban design and development. Routledge Minneapolis, USA.

- Mitchell D (1995) The end of public space? People's Park, definitions of the public, and democracy. Annals of the association of American geographers 85(1): 108-133.

- Dinesh N (2006) Environmental Psychology. Concept Publishing Company, New Delhi, India.

- Mitchell WJ (2000) Designing the digital city. In. Digital cities, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Netherlands, p. 1-6.

- Nasar JL (1994) Urban design aesthetics-the evaluative qualities of building exteriors. Environment and Behavior 26(3): 377-401.

- Nasar JL (1998) The evaluative image of the city. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, CA, USA.

- Neuman M (2005) The compact city fallacy. Journal of Planning Education and Research 25(1): 11-26.

- NorbergS (1979) Genius loci. Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, Goodreads, USA.

- Oldenburg R (1999) The great good place. cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community. De Capo Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Oldenburg R (2002) Celebrating the third place. inspiring stories about the Great Good Places at the heart of our communities. De Capo Press, Cambridge, USA.