Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Case ReportOpen Access

To Study the Gender-Wise Difference in Parenting Styles of Mother and Father Volume 2 - Issue 5

Sukanya Biswas* and Poonam Sharma

- Department of Psychology, India

Received: August 20, 2019; Published: September 06, 2019

Corresponding author: Sukanya Biswas, Department of Psychology, India

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2019.02.000148

Introduction

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Parenting is not an easy task. Becoming a parent is the easiest part, where being conscious and positive parents is a momentous task. Parenting is the most important role one face in a life time. Parents who provide an encouraging environment for their children are rewarded when as adults their children realize a successful fit into culture and society. Effective parenting enable to build and develop positive behaviours and good solid self-concept that are important to functioning fully as a healthy adult. Parenting skill can be strengthened if parent learn about themselves as a parent and about child development. Learning about the stages of human development helps parents understand about their ever changing roles in the lives of their children and also what is expected of a parent at each stage. Finally, a father’s love and influence is as importance as a mother‘s in the life of a child. Father should overcome the internal and external barrier that exits to fulfill the duties of fathering. The specific issues faced by parents change as a child grows up, at every age parent face choice about how much to respond to a child’s needs, how much control to exert, and how to exert it. Children change as they grow from infancy to early childhood and on through middle and late childhood and adolescence. Competent parent adapts to the child’s developmental changes. Researchers have long examined the impact of parenting on childhood outcomes. Often, conflicting outlooks on the best way to raise children come from any combination of biological, social, or cultural differences. What is consistent across the research is the way in which a child is nurtured and raised can impact their behavior, intelligence, academic success, mental health, social behavior, and many other aspects of their life while growing up and in the future. It is also important because parenting is crucial in helping a child adapt to and understand the world they live in; parental guidance remains an important facet in the child’s life until late adolescence where they become older and acquire the proper skills to protect and socialize themselves in the world [1]. One commonly examined factor in the child-parent relationship is influence of parenting styles.

Parenting Styles

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Parenting is a complex activity that includes ample behavior that work individually and together to influence childhood outcomes. Most researchers who attempt to describe this broad parental milieu rely on Diana Baumrind’s concept of parenting style. The study of parenting style plays an important role in the present system of education. There are four types of parenting style mainly authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent and neglectful parenting. Parenting style helps the children to develop their emotional maturity which in turn plays an important role in directing and shaping the behavior and personality. Mainly the two distinctive roles of parents include both paternal and maternal. The proper blending of masculine supervision and feminine tenderness seems to be of almost important in the upbringing of child for the most important in the normal growth what inadequate patterns of parenting may lend to despair and self-evaluation of the personality of the individual. The parental styles typically studied are authoritative parenting styles, authoritarian parenting styles, permissive or indulgent parenting styles, and neglectful or uninvolved parenting styles. These different types of parenting styles are often determined by how much or little warmth (sometimes termed acceptance or responsiveness) and control (sometimes called parental involvement) that is consistently displayed [2,3].

Authoritative Parenting

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Styles are typically attributed to being both high and healthy in the amount of warmth and control they show their children [3] through direct instruction [2] and other verbal interactions [4].This means that parents who use this method will “attempt to direct the child’s activities but in a rational, issue-oriented manner. They encourage verbal give and take, and share with the child the reasoning behind their policy” [5]. It has been suggested through research that authoritative parenting styles are associated with higher degrees of task persistence, higher-self esteem, better academic success, and so on [6]. On the other hand, Authoritarian parenting styles are likely to be high in control but low in warmth and will often discourage the amount of verbal interaction they have with their children [4]. Authoritarian parents “attempt to shape, control and evaluate their children’s behaviors and attitudes [6]” and often “value obedience as a virtue and favor punitive, forceful measures to curb self-will where the child’s actions and beliefs conflict with what they think is right conduct” [5]. As a result, children who grew up from such methods often report lower levels of self-esteem, less self-reliance, and more overall stress from challenging tasks (Hibbard & Walton, 2014) and are atypical of prosocial behavior [7,8].

In contrast, permissive-indulgent parents demonstrate high levels of warmth towards their children, but no control. Parents of this style often make few demands, allow for their children to regulate themselves with no intervention [6], and do not govern how their children should act or behave [4]. Children of this particular type of parenting style show poor grades [6], poor selfmanagement, reduced sense of support [3], and are at greater risk of developing drinking problems as adults [9]. Lastly, rejectinguninvolved parenting style is ascribed as being neither warm nor controlling- the parents of this style simply do not contribute to the relationship with the child. This parenting method “has been linked to poor emotional self-regulation, school achievement, depression, and even suicidal tendencies among females” [10,11,6].

Optimal Parenting Style

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

During the past three decades, a profusion of studies have investigated the impact of parenting style on child development. Most of this research has examined the effects of four styles of parenting: authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and uninvolved. For the most part, this research suggests that children achieve the most positive outcomes when they are reared by authoritative parents [12]. Such parents are high on both responsiveness and demandingness. Findings indicate that children of authoritative parents, regardless of age, perform better in school, display fewer conduct problems, and show better emotional adjustment than those raised in non-authoritative homes [13-19]. A summation of all the studies that were analyzed indicated that authoritative parenting was often the best in terms of positive consequences for children. From a standalone perspective, authoritative parenting styles is typically the parenting style which has been associated with the best outcomes in terms of impact on a developing child’s mental health and influence on future behaviors.

Parenting Styles and Gender

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Aside from parenting styles, there’s an interest in whether or not certain parental genders are more inclined to utilize a particular parenting style. While research about various parenting styles and their success exists, there is less research available that investigates differences in perceptions of maternal and paternal parenting or the association between certain parenting styles and parental gender [1]. At a foundational level, variations between men and women with respect to personality traits has been examined. For example, [20] found that men and women’s personalities are slightly different from one another across ten aspects of the Big Five Personality Traits, which tests the person’s: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Although slight differences in personality were evident as there were differences between scores, the study showed that culture played a massive part towards how men and women’s personalities differed [20].

Beyond individual personality traits and culture, it is important to remember that family structure matters as well. Maternal parenting styles can differ from paternal parenting styles and therefore should be examined both individually and collectively. Parents are often associated as being a functional unit in which children are raised, but both parents will often play different roles in the child’s life. Quite often, children go to each parent for different reasons. For example, children may go to their fathers if they want to play, but will go to their mothers for nurture and support. Infants are also likely to form an attachment-bond with their primary caregiver, typically mothers, and rely primarily on that caregiver in infancy as a source of nurture and sustenance [2]. It has been suggested in studies that maternal parenting styles often have the greatest effect on developing children [3]. Thus, it can be concluded that mothers and fathers play somewhat different roles in context of parenting and may have to parent and behave differently than each other, based on their respective genders, in order to be the best attuned to their child’s needs. The child naturally discriminates that the female-gendered parent is for nurturance and support and that the male-gendered parent as a playmate, thus it is important to recognize such behaviors and prepare to respond to them accordingly.

Significance of the Study

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

In 21st century we all are dealing with a time crisis! The more people get caught up in various activities the less time they have for their children. Today parent child relationship is weak and superficial; the main reason is those parents don’t get enough time to spend with their children’s. Today Parenting is being assaulted from many directions .parents are under the gun of mounting economic pressures resulting in long work hours, and often more than one job .Our 24-hour a day culture has created a job market that never goes to sleep, and many parents find themselves working hours outside of the usual nine to five workday. This leaves big gaps in childcare arrangements. Another cultural development that has significantly impacted the family is the explosion of mass media and mass communication, particularly internet style. This evolutionary step in technology has permanently changed the environment within which parents are trying to monitor and control the development of their children. The massive exposure to all kinds of information, and particularly information that is unhealthy or beyond the scope of a child’s developmental age , has placed parents in the untenable position of battling outside influences that tear at the parent-child relationship rather than assisting to safeguard family values, parental guidelines, and promote normal psychological growth. “Quality” time spend with the parents leads to positive development in the child, Trust, Love and Self independence are the essential component in a parentchild relationship. Therefore the first aim of the study is to find the frequency of most prevalent parenting styles used by the parents these days.

Children need both a mother and a father; they need both the nurturing style that most mothers bring to the family as well as a more challenging and real-world based style that seem to be innate to most fathers. So the present study focuses on how the parenting styles of fathers and mothers differ, and how can we blend them in a family to benefit the children as they grow up and prepare for life. These differing styles can be overgeneralized based on gender. In some families, mothers can be more demanding and fathers more nurturing. But the essential key is balancing the different parenting styles and getting the best impact from the blend. It is clear from the research that fathers have a critical role to play in the lives of their children. And fathers readily acknowledge that mothers are essential as well. If these parenting styles aren’t blended effectively children can feel confused or conflicted with different expectations from Mom and Dad or when parents seem so different, children can be drawn more to one parent or the other because of their affinity for the specific parenting style. Finding the appropriate balance between parenting styles is the key to success. Balancing and blending require careful thought and action. Recognizing that different styles are not bad, just different, and communicate together as parents and they will find this whole parenting much more rewarding process.

Literature Review

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Although past research suggests that children tend to benefit from being reared by an authoritative parent, much of this research has focused on mothers [21]. Researchers often assess the parenting style of mothers and assume that fathers parent in the same way. Unfortunately, we have little information regarding the extent to which this assumption is correct. Some studies have assessed the parenting styles of both mothers and fathers but then have excluded families from analysis if the parents show different parenting styles [3]. In other instances, researchers have averaged the parenting scores of mothers and fathers [17,6]. Given these methodological limitations, we have little knowledge regarding the extent to which husbands and wives show similar styles of parenting. We expect that they often display different approaches to parenting. If this is the case, it raises the issue of the manner in which these contrasting approaches to parenting influence child development. Past research has shown, for example, that authoritative parenting is more beneficial to children than indulgent parenting. To demonstrate how parenting styles affect children’s development, studies on perfectionism have indicated that parenting styles did have different effects. Families that were typically perceived by their children as authoritative would be more prone to adaptive perfectionism or at least deter them from maladaptive dimensions. Authoritarian parenting styles were positively associated with feelings of being criticized, doubts of ability, and expectations of being perfect. Children also reported feeling more anxious and overwhelmed by challenges; permissive parenting styles were positively associated with trying new challenges; neglectful styles of parenting were positively correlated with similar maladaptive dimensions that were similar to those from authoritarian parenting. In context to the development of perfectionism, authoritative parenting styles typically result in adaptive perfectionism whilst authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful parenting styles typically resulted in maladaptive and neurotic facets of perfectionism [6].

A global evaluation of [16] and [22] studies reinforced the idea that the authoritative parent was the optimal parental style. Adolescents from authoritative families would perform better in all youth outcomes examined when compared to adolescents from neglectful families. Results from authoritarian and indulgent families were less clear as they showed a mixture of positive and negative outcomes. For example, adolescents from authoritarian parents-strict but not warm-showed a reasonably adequate position of obedience and conformity with norms (they did well in school and were less likely than their peers to be involved in deviant activities); conversely, they also manifested lower selfreliance and self-competence, and higher psychological and somatic distress. And adolescents from indulgent families-warm but not strict-showed high self-reliance and self-competence, but also showed higher levels of substance abuse and school problems. According to [19], adolescents from authoritarian and indulgent families would perform on all outcomes between the maximum adjustment of the authoritative group and the minimum adjustment of the neglectful group. Studies conducted in the USA using middle-class European American samples fully supported the idea that the authoritative parenting style was always associated with optimum youth outcomes [15,16,23,22]. In addition, a number of studies conducted in other countries using different youth outcomes as criteria, also supported the idea that, compared to the authoritative style, a neglectful style of parenting corresponded with childrens’ poorest performance, whereas authoritarian and indulgent parenting occupied an intermediate position: school integration, psychological well-being United Kingdom; [24], adaptive achievement strategies, self-enhancing attributions Finland; [25], drug use Iceland; [26]), and accuracy in perceiving parental values Israel; Knafo & Schwartz, 2003). Finally, in terms of other problematic behavior such as a drinking and alcohol abuse, research once again indicates that authoritative parenting is the golden key to helping prevent some of these problems. However, in this study, it seemed that permissive parenting styles were most likely to be positively correlated with alcohol abuse. In addition, paternal permissive parenting styles especially increased sons’ consumption of alcohol, particularly beer, which tended to result with more drinking problems [9]. As noted earlier, there is strong evidence that children achieve the most positive developmental outcomes when they are reared by authoritative parents. Such parents are high on both responsiveness and control (Figures 1-3). More than three decades of research has shown that authoritative parenting is positively related to school commitment, psychological well-being, and social adjustment and negatively related to conduct problems and delinquency [15-19]. Although these studies provide important information regarding the link between various parenting styles and adolescent developmental outcomes, they do not address the issue of the consequences for children when parents engage in different styles of parenting. Past research on interparental inconsistency has focused primarily on specific parental behaviors (e.g., inconsistent expectations for the child) rather than inconsistencies in parenting style. Folbre et al (2001) said that taking care of children is a complicated mixture of work and love in which the relationship itself is very important.

Researchers have begun to study the affect of the child’s attachment to the father as well as the mother (Thompson, 2000). Father’s relationships with their children are actually very important, despite what many people may think. According to Dalton III, Frick‐Horbury, and Kitzmann (2006) reports of father’s parenting, but not mothers, were related to the quality of current relationships with a romantic partner. Also, father’s parenting was related to the view of the self as being able to form close and secure relationships. We generally expect the combination of two authoritarian parents to be rather rare. This prediction is based on our belief that there is usually no room for two authoritarian parents in one family as both will want to be in control of family decision making. Therefore, if one of the parents is authoritarian, we anticipate that the other will be either authoritative, indulgent, or uninvolved. Furthermore, based on sex role we expect mothers to be overrepresented in styles high in nurturance (indulgent and authoritative) and fathers to be overrepresented in styles characterized by strong control (authoritarian and authoritative). Based on this idea, B [13] suggests a possibly common combination that she calls traditional parenting. This refers to a family parenting style in which the mother and father enact traditional gender roles. In such cases, the mother is significantly more responsive than demanding, whereas the father is significantly more demanding than responsive. Findings from [26], [27], and [28] provide support for the idea that parents often display such a division of labor. This suggests that there should be an overrepresentation of family parenting styles consisting of an indulgent mother combined with an authoritarian father. [29] and [30] have noted, however, that fathers with a traditional gender ideology show less parental involvement than those with an egalitarian ideology. This would suggest that the consequence of traditional sex role socialization is likely to be an overrepresentation of family parenting styles containing either an authoritative or an indulgent mother with an uninvolved father. A few studies have investigated the association between family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes, but as we have noted, there are various methodological problems associated with their approach. They either assume that both parents display the same parenting style, delete families in which mothers and fathers show different styles, or average the styles of mothers and fathers. The study by Fletcher et al. (1999) explicitly considered the impact of various combinations of parenting styles on adolescent outcomes. They found that adolescents with one authoritative parent exhibited greater academic competence than did peers with parents who showed similar but nonauthoritative styles. Furthermore, adolescents with one authoritative and one nonauthoritative parent exhibited greater internalized distress than did those from families where the parents displayed similar styles. Furthermore, it is only in the case of authoritative parenting that their analyses addressed the issue of whether the benefits of a parenting style vary by gender of parent. Thus, for example, an indulgent mother paired with an uninvolved father was classified as the same family parenting style as an uninvolved mother paired with an indulgent father.

Parent Gender

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Numerous studies have established the influence of maternal parenting on adolescent adjustment [31]. A smaller body of work has demonstrated a link between fathers’ parenting and adolescent adjustment. Studies that examined both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting found considerable overlap but also some differences. For instance, in a study of parents of early adolescents, found only 29.6% rated both their parents as authoritative. Other studies found that according to both parental self-report and adolescent ratings, mothers of adolescents are more likely to use authoritative parenting than are fathers (Milevsky, Schlechter, Klem, & Kehl, 2008; Smetana, 1995) [32-36]. Consequently, adolescents with a mother who uses authoritative parenting may live in a context in which the father uses a different parenting style. It is therefore important to examine both mothers and fathers to deepen our understanding of family systems (Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006)

Parenting Similarity

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

The interdependence of maternal and paternal parenting is highlighted in several theoretical frameworks (e.g., ecological systems theory [Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994], life course theory [Elder, 1998], family systems theory[Minuchin,1985], and transactional model [Sameroff, 2009]). Although a significant minority of adolescents live in single-parent families, most North American adolescents live in two-parent families (Lofquist, Lugaila, O’Connell, & Feliz, 2012; Statistics Canada, 2012). Because research has shown that adolescents benefit from a consistent socialization environment in which each parent is predictable and reliable in affect, behavior, and limit setting (McHale & Irace, 2011), parents have been encouraged to provide a united front in their interactions with their adolescent children (Gordon, 2000). Relatively little research has examined interparental similarity and whether it promotes better child or adolescent adjustment. There is preliminary evidence that compared to having two unsupportive parents or one First, we are interested in whether adolescents achieve better outcomes when they have two rather than simply one authoritative parent. Second, we are concerned with the extent to which an authoritative parent can compensate for the less competent parenting by his or her mate. We expect that the answer to this question varies by the type of style displayed by the second parent. Although a single authoritative parent may be sufficient when the second parent is indulgent, this may not be the case when the second parent is uninvolved. Furthermore, it may be that the answer to these questions depends on the sex of the parent. Authoritative mothers may compensate for an uninvolved father, for example, whereas an authoritative father may not be able to compensate for an uninvolved mother. Finally, we are interested in whether some husband-wife combinations involving non authoritative parenting styles are as effective as having an authoritative parent. The research on authoritative parenting is often interpreted as indicating that the optimal family environment for children combines support and nurturance with structure and control (Amato & Fowler, 2002; Simons, Simons, & Wallace, 2004). However, perhaps both dimensions of parenting need not be provided by the same person. Responsiveness might be bestowed by one parent and structure and control by the other. If this is the case, an indulgent-authoritarian combination may be as effective as having one authoritative parent.

Objective

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

a) To find the frequency of most prevalent parenting style used

by girls child father.

b) To find the frequency of most prevalent parenting style used

by girls child mother.

c) To find the frequency of most prevalent parenting style used

by boys child father.

d) To find the frequency of most prevalent parenting style used

by boys child mother.

e) To find the level of using various parenting style by the father

of the girl child.

f) To find the level of using various parenting style by the mother

of the girl child.

g) To find the level of using various parenting style by the father

of the boy child.

h) To find the level of using various parenting style by the mother

of the boy child.

i) To see the gender wise difference in using different parenting

styles of the father and mother.

Hypothesis

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

a) There will be difference between the parenting style for girl

child and boy child.

b) There will be difference between mothers parenting style and

fathers parenting style.

Methodology

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Design: In the present study, descriptive survey method was employed to collect the data.

The present study intended to study the gender-wise difference in parenting styles of mother and father. So to achieve the aim of the study the following methodology was used.

Sampling

The participants of the present study comprised of 40 children of both genders within the age range of 11 to 15 years, studying in classes 6, 7th , 8th and 9th standard of English medium schools in Pune. The sample was randomly selected from the population of 500 children and was equally divided into 20 boys and 20 girls. The sample of the study was collected through the method of purposive and convenience.

Tools

A questionnaire was developed with the help of Parental Authority Questionnaire PAQ which was developed by Buri (1991) to measures perceived parenting styles, which classify parenting style as permissive, authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles. The tool consists of 30 items and to be responded on five point likert scale and indicate appropriately as to how they perceive their mother or mother figure’s parenting style. The Cronbach alpha values for the subscales range from 0.87 to 0.74. The content, criterion, and discriminant validity were also reported to be high. The present questionnaire consisted of 20 statements with 5 items in each parenting style. It is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The scale is scored by summing the individual items to compare subscale scores. The scores on each subscale range from 5 to 25. The highest score on one of the subscales indicates the parents’ parenting style. It was divided in 3 levels, children who scored between 5 to 11 was considered low, 12 to 18 was considered average and 19 to 25 was considered high on each parenting style. It being a pilot study standardization, reliability and validity is not established yet.

Inclusion Criteria: The inclusion criteria were, the children of the age group 11 to 15 years with both parents living.

Exclusion Criteria: The exclusion criteria were students absent on the day of data collection, and who had single parents children who are below 11 years of age and above 15 years of age.

Procedure

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Participants were student between the age ranges of 11 to 15 years. Permission was granted by the Principal of the school after discussing the nature of the study, the time required and assurance of complete confidentiality. Then the nature of the study was explained to the class teacher of the respective classes. Before actually conducting this study a short prior contact was made with the respective participants and the objective was explained to the participants. A letter of consent was handed over to the participants to seek permission to participate in the study from their parents. On receiving the letter of consent from parents a day was decided to carry out the actual data collection. The questionnaires were given to the respondents during the class hour. The researcher initially read and explained the instructions on how to fill in and answer the questionnaire to the respondents.

Data Analysis

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

Data collected was analyzed using the SPSS 20. Descriptive statistics was used and reported in percentages, measures of central tendency (mean and median), as well as measures of central of dispersion (standard deviation and range). Finally t-test was carried out to analyze gender differences for the parenting style among girls and boys.

Results

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

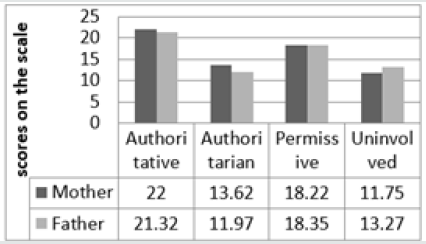

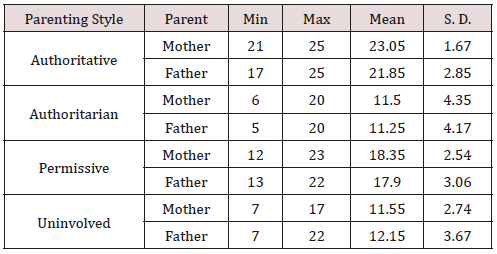

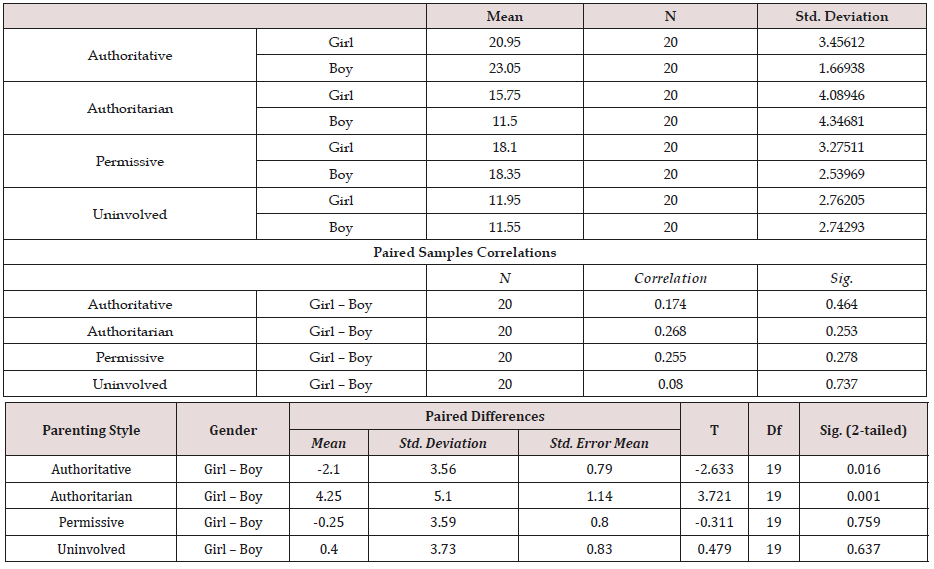

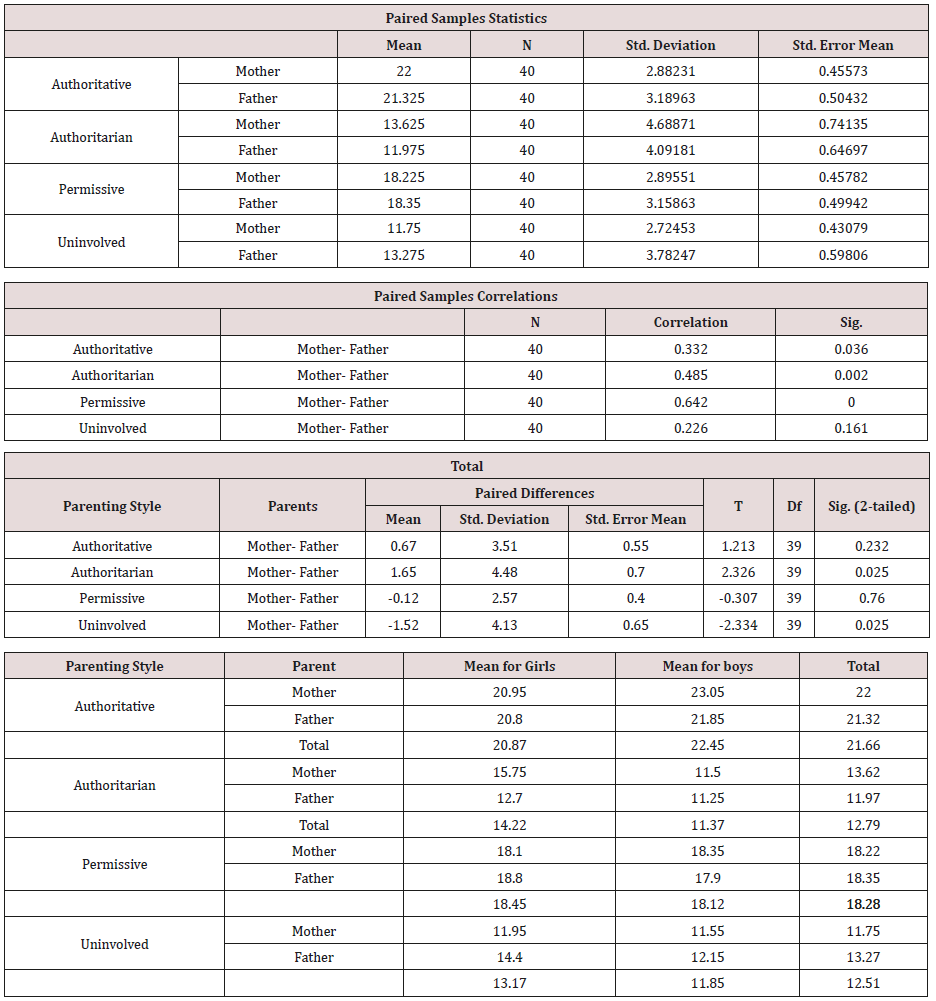

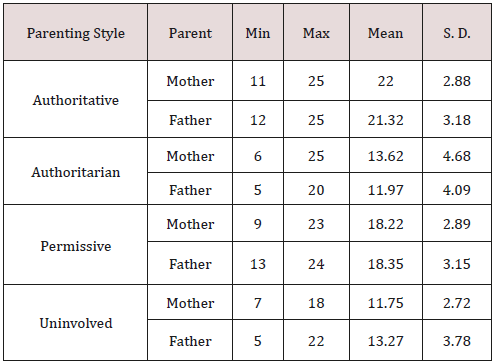

To find out the parenting style of the parents 40 children i.e. 20 boys and 20 girls were selected to find out their parenting style. In the above (Table 1) the authoritative parenting style of the mother ranged from the minimum score of 11 to the maximum score of 25 with the mean of 22.00 and standard deviation of 2.88 respectively. The authoritative parenting style of the father ranged from the minimum score of 12 to the maximum score of 25 with the mean of 21.32 and standard deviation of 3.18 respectively. The authoritarian parenting style of the mother ranged from the minimum score of 6 to the maximum score of 25 with the mean of 13.62 and standard deviation of 4.68 respectively. The authoritarian parenting style of the father ranged from the minimum score of 5 to the maximum score of 20 with the mean of 11.97 and standard deviation of 4.09 respectively. The permissive parenting style of the mother ranged from the minimum score of 9 to the maximum score of 23 with the mean of 18.22 and standard deviation of 2.89 respectively. The permissive parenting style of the father ranged from the minimum score of 13 to the maximum score of 24 with the mean of 18.35 and standard deviation of 3.15 respectively. The uninvolved parenting style of the mother ranged from the minimum score of 7 to the maximum score of 18 with the mean of 11.75 and standard deviation of 2.72. The uninvolved parenting style of the father ranged from the minimum score of 5 to the maximum score of 22 with the mean of 13.27 and standard deviation of 3.78 respectively.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of Parenting Styles. Comparison of the means for the parenting style of both the girls and the boys.

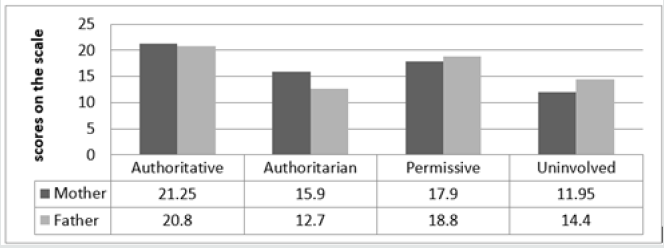

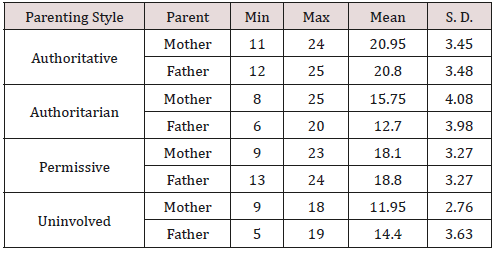

In the above (Table 2) the authoritative parenting style of the mothers of the girl child ranged from the minimum score of 11 to the maximum score of 24 (M=20.95, S.D=3.45) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 12 to the maximum score of 25 (M=20.80, S.D=3.48) respectively. In the authoritarian parenting style of the mothers of the girl child ranged from the minimum score of 8 to the maximum score of 25 (M=15.75, S.D=4.08) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 6 to the maximum score of 20 (M=12.70, S.D=3.98) respectively. In the permissive parenting style of the mothers of the girl child ranged from the minimum score of 9 to the maximum score of 23 (M=18.10, S.D=3.27) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 13 to the maximum score of 24 (M=18.80, S.D=3.27) respectively (Tables 3-5).

In the uninvolved parenting style of the mothers of the girl child ranged from the minimum score of 9 to the maximum score of 18 (M=11.95, S.D=2.76) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 5 to the maximum score of 19 (M=14.40, S.D=3.63) respectively. In the above (Table 2) the authoritative parenting style of the mothers of the boy child ranged from the minimum score of 21 to the maximum score of 25 (M=23.05, S.D=1.67) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 17 to the maximum score of 25 (M=21.85, S.D=2.85) respectively. In the authoritarian parenting style of the mothers of the boy child ranged from the minimum score of 6 to the maximum score of 20 (M=11.50, S.D=4.35) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 5 to the maximum score of 20 (M=11.25, S.D=4.17) respectively. In the permissive parenting style of the mothers of the boy child ranged from the minimum score of 12 to the maximum score of 23 (M=18.35, S.D=2.54) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 13 to the maximum score of 22 (M=17.90, S.D=3.06) respectively. In the uninvolved parenting style of the mothers of the boy child ranged from the minimum score of 7 to the maximum score of 17 (M=11.55, S.D=2.74) respectively and for the fathers ranged from the minimum score of 7 to the maximum score of 22 (M=12.15, S.D=3.67) respectively (Tables 6-9).

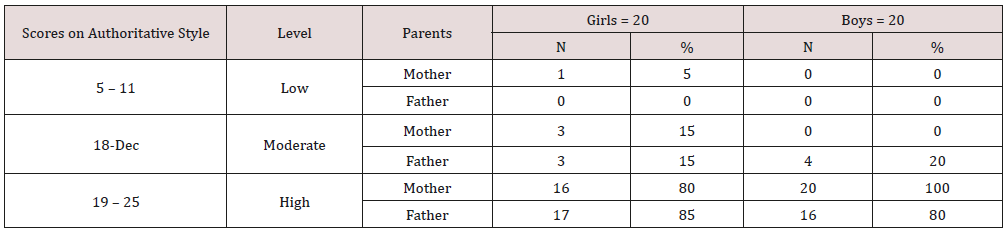

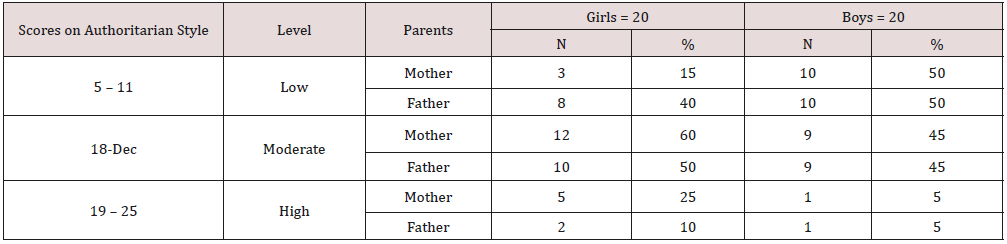

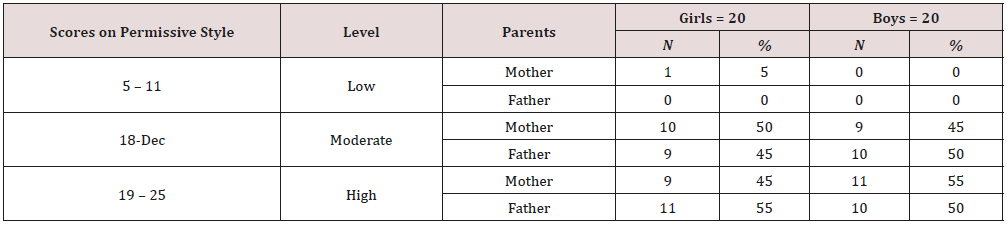

In the above table it shows that only 5% mothers for the girl child scored low in the Authoritative parenting style, with 15% in the moderate level and 80% scored on the high level. It is surprising to note that the mothers for the boy child scored 100% on the high level. Similarly the fathers for the girl child scored 15% in the moderate level and 85% scored on the high level whereas the fathers of the boy child scored 20% in the moderate level and 80% on the high level. In the above table it shows that only 15% mothers for the girl child scored low in the Authoritarian parenting style, with 60% in the moderate level and 25% scored on the high level. Whereas 50% of the mothers for the boy child scored on the low level with 45% scored in the moderate level and 5% in the high level Similarly the fathers for the girl child scored 15% in the moderate level and 85% scored on the high level whereas the fathers of the boy child scored 20% in the moderate level and 80% on the high level. In the above table it shows that only 5% mothers for the girl child scored low in the Permissive parenting style, with 50% in the moderate level and 45% scored on the high level. Whereas 50% of the mothers for the boy child scored in the moderate level and 50% in the high level. Similarly the fathers for the girl child scored 45% in the moderate level and 55% scored on the high level whereas the fathers of the boy child scored 50% in the moderate level and 50% on the high level .

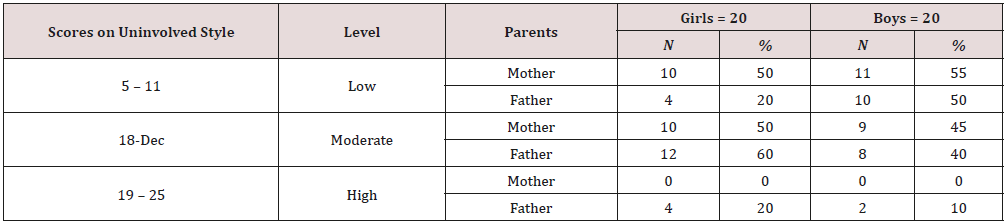

In the above table it shows that only 5% mothers for the girl child scored low in the Uninvolved parenting style, with 50% in the low level and 50% scored on the moderate level. Whereas 55% of the mothers for the boy child scored in the low level and 45% in the moderate level. Similarly the fathers for the girl child scored 20% in the low level, 60% in the moderate level and 20% scored on the high level whereas the fathers of the boy child scored 55% in the low level, 40% in the moderate level and 10% on the high level.

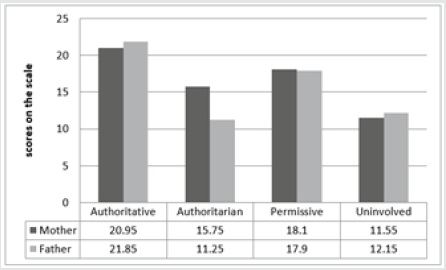

As shown in the (Table 5), there is a significant difference between mean in using authoritative parenting style for the girls and boys (p 05/0 <), where the extent to use authoritative parenting style for boys (23.05) is significantly more than the one for the girls (20.95). In using authoritarian parenting style, there is a significant difference between the girls and the boys (p 05/0<) and parents use authoritarian parenting style for girls (15.75) more than for boys(11.50). No significant difference was observed among boys and girls in using permissive and uninvolved parenting style. As shown in the (Table 5), there is a significant difference between mean in using authoritarian parenting style of the mothers and fathers (p 05/0 <), where the extent to use authoritarian parenting style for the mother (13.62) is significantly more than the that of the father (11.97). In using uninvolved parenting style, there is a significant difference between the mother and the father (p 05/0< ) and parents use uninvolved parenting style for the father(13.27) more than the mothers (11.75). No significant difference was found between the mother and the father authoritative and permissive parenting style.

Discussion

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

The present study intended to study the gender-wise difference in parenting styles of mother and father. The participants of the present study comprised of 40 children of both genders within the age range of 11 to 15 years, studying in classes 6, 7th, 8th and 9th standard of English medium schools in Pune. The sample was randomly selected from the population of 500 children and was equally divided into 20 boys and 20 girls. The sample of the study was collected through the method of purposive and convenience. A questionnaire was developed with the help of Parental Authority Questionnaire PAQ which was developed by Buri (1991) to measures perceived parenting styles, which classify parenting style as permissive, authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles. The tool consists of 30 items and to be responded on five point likert scale and indicate appropriately as to how they perceive their mother or mother figure’s parenting style. The highest score on one of the subscales indicates the parents’ parenting style. It was divided in 3 levels, children who scored between 5 to 11 was considered low, 12 to 18 was considered average and 19 to 25 was considered high on each parenting style.

The above result clearly states that the mothers and the fathers employed more authoritative style to their boys (m=23.05, m=21.08), as compared to their girls (m=20.95, m=20.8). Whereas, for both mothers and fathers, effects of authoritative style are higher on girls (m=15.75, m=12.7) as compared to boys (m= 11.5, m=11.25). Effects of permissive style show consistent outcomes, both mothers and fathers are more permissive to girls (m=18.1, m=18.35), as compared to boys (m=18.8, m=17.9). In the case of uninvolved style, the mothers scored similar for the girls and boys (m=11.95, m=12.15) whereas the fathers employed more uninvolved style to their girls as compared to their boys (m=14.4, m=12.15). Very few studies have examined sex of parent differences in parenting, and the ones that have mostly focused on the amount of parent involvement, rather than choices of parenting style (Fagan, 2000). Research has supported that mothers and fathers use the same disciplinary styles with their children sixty five percent of the time (Hart, Dewolf, Wozniak & Butts, 1992). Therefore it is important to determine each parent’s style. It was observed that mothers and fathers make individual contribution to the development of children. Fathers have been less frequently studied in the relation to effects they have on children’s developmental outcomes. Some research has focused on the different parenting styles related to the sex of the child (Bornstein 2002; Flannagan & Hardee 1994). Interactions between mothers and sons have been shown to involve greater emotion than mother-daughter relationship . While affection from the same-sex parent is linked to positive developmental out comes for the child (Bornstein, 2002). Fathers use more power-assertive styles of interaction, which makes them a natural fit to the authoritarian parenting style. (Russell, Robinson, Olsen 2003). In comparison to mothers, Fathers are described to be less accepting, less likely to initiative interactions, but as competent as mothers (Collins & Russsel, 1991). Mother and Father rear females restrictively and with greater attention whereas the males perceived both their parents as treating them more negatively than females (Dominguez .M,Melina ;1997). The above result shows that the frequency of the various parenting styles used for both the girls and the boys. The results indicated that there are statistically significant differences in the frequency with which the parenting styles occur. The first most common parenting style reported by children is Authoritative followed by the permissive style. Using child’s score, both mothers and fathers exhibit behaviors consistent with the authoritarian followed very closely by uninvolved style of parenting. Difference in t- tests indicated that there were significant differences between the scores of mothers and fathers on the authoritarian and uninvolved style of parenting.

The above results in the t-test also shows that when compared the parenting style between the girl child and the boy there was a significant difference in the authoritative style and authoritarian parenting style between the girl child and the boy child. Difference in t-tests indicated that that the mothers were more likely to parent the boy child in authoritative style as compared to their girl child. Whereas the fathers were more likely to be authoritarian with the girls as compared to the boys. A significant difference was not observed in using uninvolved and permisive parenting style for the girls and the boys. The findings of this part are not relevant with the findings of the study by Gerami (2008). Findings of the study by Gerami (2008) showed that mothers use the rational authoritative parenting styles more where there is not a significant difference in using parenting styles among males and females. To define these findings of this paper, one can say that the parents’ parenting styles are different for males and females so that parents use authoritative parenting style and authoritarian parenting style for males and females, respectively. To confirm this fact, it can say that the reason for the difference in parents’ parenting styles among males and females might be attributed to the cultural, social and family factors. Many of the findings of this survey go along with stereotypical beliefs about parenting, for example, the finding that fathers are significantly more overprotective and dominant of their daughters than of their sons. This probably has to do with the belief that women need protection from men and that men are more independent and can make their own decisions. Also, the finding in this study that mothers are more overprotective and caring than fathers probably has to do with the fact that mothers spend more time with their children than fathers. Stereotypically, a father’s role is often seen as a provider role, and a mother’s role is seen as the caretaker’s role (Gerson, 2002). Also the finding that mothers are perceived on average as spending more time taking care of their children than fathers even when working full time supports what we know about the second shift and men and women’s perceived responsibility in and out of the home (Hochschild, 2003). From this analysis, it is clear that parenting styles should not be considered as independent from aspects such as culture and gender, both of which both play a massive role in influencing how parenting styles are conveyed to children. During research, the reoccurring theme that authoritative parenting had the most reliable and significant outcomes on positively affecting emotional intelligence, mental health, self-esteem, self-regulation, as well as likelihood of prosocial behavior [3,11,7,5]. All other parenting styles seemed to fall short or were negatively associated with said traits. Some studies suggested that the parenting styles besides authoritative parenting style were positively associated with problematic behavior such as alcohol abuse [13] and harmful behavior to oneself or others [5,11]. In addition, some of these studies found that, while parental gender does affect certain outcomes, parenting styles being shared amongst parents is also an incredibly important factor which affects children’s’ development [11,7,3]. Collectively, this research suggests that culture does impact how a child is raised, but culture cannot be viewed independently from other factors such as parenting style and gender. Research also indicated that certain parenting styles may elicit different responses in children of different gender. In addition to these findings, parental gender may often play a role in the overall parenting experience.

For example, authoritative parenting styles will make both genders report higher overall emotional intelligence, but males are more apt in even higher scores when compared to high scoring females [3]. In contrast, permissive parenting especially from the paternal side would negatively affect male children and result in a higher chance of developing drinking problems in the future [13]. These studies also reaffirmed that authoritative parenting styles from both parents typically evoked the best responses from their children in the form of reports of higher self-esteem, better grades and school performance, improved mental health, and many other beneficial facets of life. Based on the literature for cultural research in relation to parenting styles, we know that parental nativity can impact the socialization of certain cultural and traditional genderrole values [7]. In some cases, cultures that are governed by more traditional patriarchal societies where traditional gender-roles are enforced may be more likely to show differences in parenting styles between paternal and maternal parenting. In addition, it is evident that paternal and maternal parents play different roles in the development of children. Whereas the child may seek their mother out to be the primary-caretaker and a source of nurturing and sustenance, the father may be the individual who enforces rules and is responsible for playing with the child.

Limitations

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

a) The size of the sample was only 40.

b) The study can be stronger with regards to statistics by using

standardized scales.

Conclusion

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

The research findings depicted that when compared the parenting style between the girl child and the boy there was a significant difference in the authoritative style and authoritarian parenting style between the girl child and the boy child. Difference in t-tests indicated that that the mothers were more likely to parent the boy child in authoritative style as compared to their girl child. Whereas the fathers were more likely to be authoritarian with the girls as compared to the boys. A significant difference was not observed in using uninvolved and permissive parenting style for the girls and the boys. Congenial home environment and healthy parenting are crucial for proper development of children. Unfortunately, it does not happen in case of each and every family. For proper physical development a child needs balanced diet. Likewise for healthy mental development a child needs balanced love and affection. Over regimented attitude in the form of strict parental disciplinary measures and/or over indulgence in the form of too much love and affection are equally harmful for development of socially desirable behaviour among children. The strongest factor in moulting a child’s personality is his relationship with his parent. If his parent love him with a generous, even flowing, non-possessive affection and if they treat him as a person who like themselves, has both rights and responsibilities in the family group, then his chances of developing normally are good. But if they diverge from this desired pattern, the child’s development may be distorted. The findings of the study indicate that majority of the parents adopted authoritative parenting style followed by permissive parenting styles and authoritarian and uninvolved.

Suggestion for Further Studies

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

a) Research is necessary to clarify the causal role of parenting

and the parent-child relationship in regard to gender.

Further research required to determine whether parenting and

quality of parent-child relationships play a role in determining how

other factors –such as peer influence –culture, parents personality,

belief contributes to their parenting style.

References

- Introduction

- Parenting Styles

- Authoritative Parenting

- Optimal Parenting Style

- Parenting Styles and Gender

- Significance of the Study

- Literature Review

- Parent Gender

- Parenting Similarity

- Objective

- Hypothesis

- Methodology

- Procedure

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Suggestion for Further Studies

- References

- Adalbjarnardottir S, Hafsteinsson LG (2001) Adolescents' perceived parenting styles and their substance use: Concurrent and longitudinal analyses. Journal of Research on Adolescence 11: 401-423.

- Argyriou E, Bakoyannis G, Tantaros S (2016) Parenting Styles and Trait Emotional Intelligence in Adolescence. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 57: 42-49.

- Aunola K, Stattin H, Nurmi JE (2000) Parenting styles and adolescents' achievement strategies. Journal of Adolescence 23(2): 205-222.

- Barton AL, Kirtley MS (2012) Gender Differences in the Relationships Among Parenting Styles and College Student Mental Health.Journal of American College Health 60(1): 21-26.

- Berk SF (1985) The gender factory: The apportionment of work in American households. New York: Plenum.

- Davis AN, Carlo G, Knight GP (2015) Perceived Maternal Parenting Styles, Cultural Values, and Prosocial Tendencies Among mexican American Youth. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 176(4): 235-252.

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman, PH, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ (1987) The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development 58(5): 1244-1257.

- Hibbard DR, Walton GE (2014) Exploring the Development of Perfectionism; The Influence of Parenting Styles and Gender. Social Behavior and Personality 42(2): 269-278.

- Kail RV, Ateah CA, Cavanaugh JC (2006) Human development: A Life-Span View. Toronto: Thomson Nelson.

- Uji M, Sakamoto A, Adachi K, Kitamura T (2014) The Impact of Authoritative, Authoritarian, and permissive Parenting Styles on Children’s Later Mental Health in Japan: Focusing on Parent and Child Gender. J Child Farm Study 23(2): 293-302.

- Weisberg YJ, DeYoung CG, Hirsh JB (2011) Gender Differences in Personality across the ten aspects of the Big Five. Frontiers in Psychology 2: 178.

- Whitney N, Freeland JM (2015) Parenting Styles, Gender, Beer Drinking and Drinking Problems of College Students. International Journal of Psychology: A Biopsychosocial Approach 16: 93-109.

- Carlo, Gustavo, Fabes, Richard A, Laible, et al. (1999) Early Adolescence and Prosocial/Moral Behavior II: The Role of Social and Contextual Influences (1999).

- Baumrind D (1987) A developmental perspective on adolescent risk-taking in contemporary America. In W. Damon (Ed.), New directions for child development: Adolescent health and social behavior 37: 93-126.

- Ehnvall A, Parker G, Hadzi Pavlovic D, Malhi G (2008) Perception of rejecting and neglectful parenting in childhood relates to lifetime suicide attempts for females-but not for males. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 117(1): 50-56.

- Lamborn SD, Mounts NS, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM (1991) Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development 62(5): 1049-1065.

- Coltrane S (2000) Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family labor. Journal of Marriage and Fa, pp. 1208-1233.

- Baumrind D (1991) Parenting styles and adolescent development. International Journal of Brooks The encyclopedia of adolescence, pp.746-758.

- Parke RD (1996) Fatherhood. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Maccoby EE, Martin JA (1983) Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P Mussel (Eds), Handbook of Child Psychology, pp. 1-101

- Dornbush S, Ritter P, Lieberman P, Roberts D, Fraleigh M (1987) The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development 58: 1244-1257.

- Gray MR, Steinberg L (1999) Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multi-dimensional construct. Journal of Marriage and Family 61: 574-587.

- Lamborn SD, Mounts NS, Steinberg L, Dornbusch, SM (1991) Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent,and neglectful families. Child Development 62(5): 1049-1065.

- Steinberg L, Elmen J, Mounts N (1989) Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success in adolescents. Child Development 60(6): 1424-1436.

- Steinberg L, Lamborn S, Dornbusch S, Darling N (1992) Impact of parenting practices on adolescent commitment: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63(5): 1266-1281.

- Steinberg L, Mounts N, Lamborn S, Dornbusch S (1991). Authoritative parenting andadolescent adjustment across various ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence 1(1): 19-36.

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, Mounts NS, Dornbusch SM (1994) Over-Time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development 65(3): 754-770.

- Shucksmith J, Hendry LB, Glendinning A (1995) Models of parenting: Implications for adolescent well-being within different types of family contexts. Journal of Adolescence 18(3): 253-270.

- Marsiglio W, Amato P, Day RD, Lamb ME (2000) Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and Family 62(4): 1173-1193.

- Baumrind D (1973) The development of instrumental competence through socialization. In A. Pick (Ed.),Minnesota symposium on child psychology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 7: 3-46.

- Radziszewska B, Richardson JL, Dent CW, Flay BR (1996) Parenting style and adolescent depressive symptoms, smoking, and academic achievement: Ethnic, gender, and SES differences. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 19(3): 289-305.

- Bulanda RE (2004). Paternal involvement with children: The influence of gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and Family 66(1): 40-45.

- Sabattini L, Leaper C (2004) The relation between mother’s and father’s parenting styles and their division of labor in the home: Young adults’ retrospective reports. Sex Roles 50(3): 217-225.

- Steinberg C, Sellers L (1999) Adolescents’ well-being as a functionof perceived interparental inconsistency. Journal of Marriage and Family 61(3): 599-610.

- Hofer C, Eisenberg N, Spinrad, TL, Morris AS, Gershoff E, et al. (2013) Mother-Adolescent conflict: Stability, change, and relations with externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.Social Development 22(2): 259-279.

- Lanza H, Huang, DY, Murphy DA, Hser YI (2013) A latent class analysis of maternal responsiveness and autonomy-granting in early adolescence: Prediction to later adolescent sexual risk-taking. Journal of Early Adolescence 33: 404-428.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...