Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

The Triad of Commitment in Local Governments: Support, Commitment and Presenteeism in the Public Sector Volume 8 - Issue 5

Maria do Rosário Fernandes and Ana Palma-Moreira*

- Maria do Rosário Fernandes and Ana Palma-Moreira*

Received: June 16, 2025; Published: June 24, 2025

Corresponding author:Ana Palma-Moreira, Faculty of Science and Technology, European University, Quinta do Bom Nome, Estr. da Correia 53, 1500-210 Lisbon, Portugal.

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2025.08.000299

Abstract

This study aims to investigate the effect of perceived organizational support on organizational commitment among local government employees and its relationship with presenteeism. The sample consists of 234 participants, employees of local authorities in Portugal. Cognitive perception of organizational support positively and significantly affects presenteeism and affective commitment. Affective perception of organizational support positively and significantly affects affective commitment. Only affective commitment has a negative and significant effect on presenteeism. Contrary to expectations, no mediating effect was found. The results obtained in this study contribute to a better understanding of the dynamics between organizational support, commitment and presenteeism, especially in the context of local authorities. Understanding these relationships is essential for developing strategies that promote a healthy and productive work environment in local authorities.

Keywords: Perception of Organizational Support; Organizational Commitment; Presentism; Relationships between Variables

Introduction to Force-based Nightmare

Organizational support precession is a central element in the dynamics of employee behavior, playing a fundamental role in shaping the work environment. Defined as the set of values, beliefs, and practices that guide the behavior of members of an organization [1], organizational support processes directly influence the commitment and psychological health of employees. In an environment where precession emphasizes physical presence over actual productivity, the characteristics of presenteeism can become dominant. This behavior, characterized by being present at work without the ability to perform tasks effectively, not only impairs individual performance but also impacts team qualities and organizational results [2]. Presenteeism, often considered the opposite of absenteeism, has gained attention from researchers and managers due to its significant effects on employee productivity and well-being. Understanding presenteeism is essential for developing prevention and mitigation strategies, as well as improving the work environment and organizational outcomes. On the other hand, organizational commitment is a critical variable that the precession of organizational support can influence. It refers to the degree of leadership and identification of the employee with the organization, manifesting itself in three dimensions: affective, normative and calculative [3].

Organizations that cultivate support, recognition and professional development increase employee commitment, especially affective commitment. This not only improved team morale but also fostered a more positive and collaborative work environment, where employees felt motivated to contribute to organizational goals. The relationship between organizational commitment and presenteeism also deserves attention. Research indicates that employees who feel committed and involved in their jobs are less likely to be absent or to work in poor health [4]. Thus, a high level of commitment can serve as a protective factor against presenteeism, leading to increased productivity and a healthier work environment. In addition, organizational commitment (especially affective commitment) can have a mediating effect on the relationship between organizational support and presenteeism. Support that promotes flexibility, well-being and mental health can not only increase commitment but also reduce the incidence of presenteeism. This suggests that interventions designed to enhance organizational support, such as wellness programs, flexible work policies, and recognition initiatives, can lead to a substantial increase in employee satisfaction and performance [5].

In short, exploring these interrelationships offers a valuable opportunity for organizations seeking to improve employee wellbeing and operational efficiency. Research on these topics is vital, especially in a context where mental health and work-life balance are increasingly recognized as fundamental to organizational success.

Research Question:

Is organizational commitment the mechanism that explains the relationship between organizational support precession and presenteeism among local government employees?

Research Objectives:

To study the relationship between organizational support precession and presenteeism among local government employees.

To study the mediating effect of organizational commitment on the relationship between organizational support and presenteeism among local government employees.

Literature Review

Perceived Organizational Support

Perceived Organizational Support Perception (POS) refers to employees’ belief about how much the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being [6]. Studies show that a high perception of organizational support is associated with several positive outcomes, including greater job satisfaction, organizational commitment and performance [6,7]. Several factors, such as the quality of relationships between managers and subordinates, organizational communication and human resource policies, can influence POS. When employees feel that the organization is willing to support them, they tend to develop greater emotional commitment to the company, which in turn can reduce turnover intention and increase productivity [3]. Additionally, POS can serve as a valuable resource during times of stress and workplace difficulties. When employees perceive that the organization is willing to offer support, they feel more resilient and capable of facing challenges, resulting in a healthier work environment [7]. Therefore, promoting a culture of organizational support can be an effective strategy for improving employee wellbeing and, consequently, organizational performance.

Presenteeism

Presenteeism is a phenomenon that occurs when employees are physically present at work but are unable to perform their duties effectively due to health issues, stress, or other personal problems. This situation can arise for a variety of reasons, including physical or mental illness, lack of motivation, pressure to perform or an organizational culture that values presence over productivity [2]. In environments where a culture of “being present” is prevalent, employees may feel compelled to come to work even if they are not in a position to contribute fully to the organization’s goals. The consequences of presenteeism can be detrimental to both individual performance and the team’s collective performance. Employees who are present but not productive can delay projects, increase their colleagues’ workload and reduce team morale, resulting in a decline in work quality and customer satisfaction [8]. In addition, presenteeism is often associated with mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. Employees who feel overwhelmed or stressed may choose to come to work even when they are not in good health, perpetuating a cycle of stress and dissatisfaction [9]. This phenomenon can result in significant costs for organizations, which face losses related to low productivity, increased turnover, and a deterioration of the organizational climate. To mitigate presenteeism, organizations can adopt strategies that promote a healthy work environment, such as wellness policies, mental health programs, work flexibility, and a culture that values productivity over mere presence [10]. Encouraging employees to take time off when needed and to prioritize their health can contribute to reducing presenteeism. In short, presenteeism is a complex issue that affects both employees and organizations. Addressing this phenomenon is crucial to fostering a healthier and more productive work environment where employees feel empowered to prioritize their health and well-being.

Perceived Organizational Support and Presentism

Firstly, positive POS tends to reduce presenteeism. When employees feel that the organization cares about their wellbeing, offers support and recognizes their contributions, they are more likely to feel valued and motivated. This can lead to greater commitment to the organization and a willingness to take care of their health, resulting in a lower incidence of presenteeism [6]. Employees who perceive organizational support often feel more comfortable taking time off, when necessary, rather than coming to work when they are not in a fit state to perform their duties. On the other hand, presenteeism can negatively influence the perception of organizational support. Employees who feel compelled to be present at work, even when they are not in a suitable condition, may begin to question the organizational culture and the effectiveness of the support they receive. If they perceive that the organization values physical presence over well-being, this can create a sense of devaluation and disenchantment, leading to a decrease in POS [2]. This decrease in perceived support can, in turn, increase the risk of mental and physical health problems, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

In addition, presenteeism can affect the organizational climate, creating an environment where employees feel pressured to attend work, even under adverse conditions. This can result in increased stress and job dissatisfaction, which, in the long run, can erode POS. When employees feel they need to sacrifice their health to meet attendance expectations, their perception of organizational support deteriorates [8]. In summary, the relationship between perceived organizational support and presenteeism is complex and bidirectional. Positive POS can help reduce presenteeism, while presenteeism can undermine the support employees feel from the organization [11]. To promote a healthy and productive work environment, organizations should focus on improving POS by creating a culture that values employee well-being and encourages open communication about health and work performance [12].

Hypothesis 1: Perceived organizational support (affective and cognitive) has a significant negative effect on presenteeism.

Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment is a fundamental concept in the field of human resource management, referring to the degree of loyalty and identification that an employee develops towards their organization. This commitment can manifest itself in several dimensions, the most recognized being the affective, normative and calculative dimensions. Affective commitment refers to the emotional connection that the employee feels towards the organization. Employees with high affective commitment identify with the company’s values and goals, feeling motivated to contribute to its success. This emotional connection is often associated with greater commitment and job satisfaction [3]. On the other hand, normative commitment refers to the perceived obligation that employees feel towards the organization. This can be influenced by factors such as organizational culture, social norms or external expectations. Employees who demonstrate strong normative commitment may feel that they should remain in the organization, even if their emotional motivations are not as strong. Calculative commitment, on the other hand, relates to the rational assessment of the costs and benefits of remaining in the organization. Employees with calculative commitment may feel that they have more to lose than to gain by leaving the company due to factors such as financial benefits, job security or the difficulty of finding a new opportunity [13].

Organizational commitment is a crucial factor for the longterm effectiveness and sustainability of organizations. Committed employees tend to be more productive, have lower absenteeism rates and are more likely to contribute positively to the organizational climate [14]. In addition, organizational commitment is associated with talent retention, as employees who feel valued and connected to the organization are less likely to seek opportunities elsewhere. Organizational commitment can be promoted through various strategies, including professional development, recognition of achievements, creation of a positive work environment, and building an organizational culture that values diversity and inclusion [15]. When organizations invest in their people and promote a supportive environment, they not only increase commitment but also improve employee satisfaction and overall organizational performance. In short, organizational commitment is a key determinant of employee behavior and organizational health. Understanding and fostering this commitment can lead to a more productive and satisfying work environment, benefiting both employees and the organization itself.

Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Commitment

Perceived organizational support (POS) and organizational commitment are significantly interlinked, with each influencing the other in various ways. Let us explore these relationships. First, positive OS tends to increase organizational commitment. When employees see that the organization cares about their well-being, offers support and recognises their contributions, they feel more valued and, consequently, more committed to the company [6]. This feeling of support creates a stronger emotional connection, leading employees to identify more with the organization ‘s goals and values [16]. Employees who feel that the company invests in them and that their needs are met are more likely to develop loyalty and a sense of belonging. On the other hand, a high level of organizational commitment can have a positive impact on POS. Committed employees are more involved in the organization ‘s activities and contribute to a positive work environment. This contribution can include promoting a culture of support and collaboration, where colleagues help each other and share positive experiences [3]. This dynamic can reinforce the perception of organizational support, as a collaborative environment facilitates communication and recognition of employees’ needs.

However, the relationship can also be affected by negative factors. If POS is perceived as low - for example, if employees feel that they do not receive support when needed or that their concerns are not taken seriously - this can lead to a decrease in organizational commitment. Employees who feel undervalued may become emotionally distanced from the organization, which can result in lower motivation and commitment [2]. Similarly, weak organizational commitment can have a negative impact on OSP. Unmotivated employees may not strive to promote a supportive climate, resulting in an organizational culture that does not foster perceptions of support. This lack of commitment can create a vicious cycle, where deteriorating OSP leads to decreased commitment, perpetuating dissatisfaction. In summary, the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment is complex and bidirectional. Positive OSP can strengthen commitment, while strong commitment can improve OSP. To promote a healthy and productive work environment, organizations must strive to improve both dimensions, creating a culture of support and appreciation that benefits both employees and the organization itself [17].

Hypothesis 2: The perception of organizational support (affective and cognitive) has a positive and significant effect on organizational commitment (affective, calculative and normative).

Organizational Commitment and Presenteeism

Organizational commitment and presenteeism are significantly interlinked, with each influencing the other in several ways. These relationships are explored below. Firstly, a high level of organizational commitment tends to reduce presenteeism. Employees who feel committed to the organization and identify with its values and goals are more likely to prioritize their health and well-being. They recognize the importance of being at full capacity to contribute effectively, which leads them to take time off when they are sick or facing difficulties [14]. Thus, strong commitment can encourage employees to seek a balance between work and health, resulting in fewer cases of presenteeism. On the other hand, presenteeism can negatively affect organizational commitment. When employees feel pressured to be present at work, even in inappropriate conditions, this can lead to resentment and demotivation. This culture of forced attendance can lead to a decrease in commitment, as employees may feel that their health and well-being needs are not valued [2]. This disconnect can result in a decline in loyalty and identification with the organization.

In addition, presenteeism can impact on the organizational climate, creating an environment where the mental and physical health of employees is compromised. In a scenario where employees feel compelled to show up even when they are unwell, team morale can be damaged, leading to increased stress and job dissatisfaction. This, in turn, can erode organizational commitment, as dissatisfied employees tend to distance themselves from the company’s culture and goals [8]. On the other hand, when organizations promote an environment that values well-being and health, this can strengthen organizational commitment. Policies that encourage open communication about health, flexibility at work and support in times of need contribute to a positive climate where employees feel safe to prioritise their health. This support can increase employee loyalty and identification with the organization. In summary, the relationship between organizational commitment and presenteeism is complex and bidirectional. Strong organizational commitment can help reduce presenteeism, while presenteeism can undermine commitment. To promote a healthier and more productive work environment, organizations should focus on strategies that encourage commitment, value employee well-being, and create a culture of support and understanding. This not only minimizes presenteeism but also strengthens employees’ loyalty and commitment to the organization.

Hypothesis 3: Organizational commitment (affective, calculative and normative) has a significant negative effect on presenteeism.

Perceived Organizational Support, Presenteeism and Organizational Commitment

Perceived organizational support (POS), organizational commitment and presenteeism are intricately linked, forming a cycle where each element can influence and be influenced by the others. Let us examine how these three factors interact with one another.

1. Perceived Organizational Support (POS) and Organizational Commitment: When employees perceive that the organization cares about their well-being, offers support and recognizes their contributions, this tends to increase organizational commitment. Positive OSP fosters a sense of appreciation and loyalty, enabling employees to identify more closely with the company’s mission and goals. On the other hand, committed employees are more likely to engage in behaviors that promote a supportive environment, strengthening OSP [6].

2. Organizational Commitment and Presenteeism: A high level of organizational commitment can reduce presenteeism. Employees who feel committed and identified with the organization tend to prioritize their health and well-being, which leads them to take time off when necessary, rather than coming to work in unsuitable conditions [14]. On the other hand, presenteeism can negatively affect organizational commitment. When employees feel compelled to be present at any cost, this can lead to demotivation and resentment, reducing loyalty and identification with the organization [2].

3. Perceived Organizational Support (POS) and Presenteeism: A positive perception of organizational support can help reduce presenteeism. When employees feel that the organization values their health and well-being, they are more likely to take time off when they are sick or facing difficulties. This contributes to a healthier work environment (Hemp, 2004). On the other hand, presenteeism can negatively impact OSP, as an environment where employees feel pressured to be present, even under adverse conditions, can lead to a perception that the organization does not care about their well-being, resulting in mistrust and disengagement. In a study linking POS with organizational commitment and absenteeism, Fsafy-Godineau and Carassus [18] concluded that organizational commitment mediates the relationship between POS and absenteeism. In summary, POS, organizational commitment and presenteeism form an interdependent cycle. Positive POS strengthens organizational commitment, while strong commitment helps to promote a supportive environment. At the same time, high commitment can reduce presenteeism, while presenteeism can undermine commitment and POS. To create a healthy and productive work environment, organizations must work to improve all these aspects by promoting a culture of support, appreciation and well-being.

Hypothesis 4: Organizational commitment (affective, calculative and normative) has a mediating effect on the relationship between perceived organizational support (affective and cognitive) and presenteeism.

The research model presented in Figure 1 summarizes the hypotheses formulated in this study (Figure 1).

Method

Data Collection Procedure

This study involved 235 local government employees in Portugal; however, only 234 individuals met the conditions to participate. Data collection was conducted using a non-probabilistic, intentional, snowball sampling procedure [19], which allowed participants to recruit other employees for the research. The study will be exploratory and cross-sectional, as data will be collected at a single point in time. The questionnaire was made available online through the Google Forms platform and was shared via links on communication tools such as Gmail, WhatsApp, LinkedIn and Instagram. In the introduction to the questionnaire, participants received information about the research objectives and a guarantee of confidentiality regarding the data provided. Participants were asked to respond to scales measuring Perceived Organizational Support, Organizational Commitment and Presenteeism. In addition, sociodemographic information was requested to enable a comprehensive characterization of the sample. Data collection took place between January and March 2025.

Participants

The sample analyzed consists of 234 participants, aged between 24 and 68, with an average age of 47.42 and a standard deviation of 9.360. In terms of gender, most participants are female, representing 68.5% of the sample, while 31.5% are male. In terms of educational level, 24.3% of participants hold a degree equivalent to or lower than a 12th-grade education, 53.2% hold a bachelor’s degree, and 22.6% hold a master’s degree or higher. Regarding seniority in the organization, 5.1% of participants have been there for less than a year, 13.2% are in the 1 to 3-year range, 17% from 4 to 6 years, 8.1% from 7 to 10 years, 8.1% from 11 to 15 years and 48.5% have more than 15 years of experience. Regarding the type of employment contract, 14% of participants have an indefinite contract, 7.7% have a fixed-term contract, 75.7% are on a permanent contract, and 2.6% have another type of contract. In terms of marital status, 23.4% are single, 58.7% are married or in a civil partnership, 16.6% are divorced or separated, and 1.3% belong to another category. Regarding children, 27.2% of participants do not have children, while 72.8% report having them. Finally, the geographical distribution of participants reveals that 63.4% live in Lisbon, 14% in Faro, 10.2% in Setúbal, 3.8% in Beja, 6.8% in Leiria, and 0.4% in Évora, Aveiro, Bragança and Castelo Branco. This data provides a comprehensive overview of the demographic and professional characteristics of the study participants.

Data Analysis Procedure

After data collection, the data were imported into SPSS Statistics for Windows 30 software. Data analysis began by testing the metric qualities of the instruments used in this study. For reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated, which should be equal to or greater than 0.70. To test the sensitivity of the items, measures of central tendency and shape were calculated. The items should not have the median close to either extreme, should have responses at all points, and their absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis should be below 2 and 7, respectively. For the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, t-tests were performed using the sample. To test the effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study, t-tests for independent samples and One-Way ANOVA were performed. To test the association between the variables under study, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. The hypotheses formulated were tested using simple and multiple linear regressions.

Instruments

The online questionnaire consisted of three instruments and several sociodemographic questions. To measure the perception of organizational support, the SPOS (Survey of Perceived Organizational Support) instrument, developed by Eisenberger et al. [20] and adapted for the Portuguese population by Santos and Gonçalves [15], consisting of two dimensions: affective (items 1, 4, 6 and 8) and cognitive (items 2, 3, 5 and 7). The items are classified on a seven-point Likert scale (from 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘Strongly agree’). To measure presenteeism, an instrument developed by Ozminkowski et al. [21] and adapted for the Portuguese population by Ferreira et al. [22] was used, consisting of eight items. These eight items are classified on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1, “All the time,” to 5, “None of the time”). Organizational commitment was measured using the instrument developed by Meyer and Allen [23] and adapted for the Portuguese population by Nascimento et al. [24], consisting of 19 items distributed across three dimensions: affective commitment (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6); calculative commitment (items 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13); normative commitment (items 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19). These items were assessed on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘Strongly agree’). All instruments in this study show good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values above .70, the minimum acceptable in organizational studies. All items have responses at all points. No item has a median close to either extreme. Their absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis are below 2 and 7, respectively, which indicates that they do not grossly violate normality [25].

Results

Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Under Study

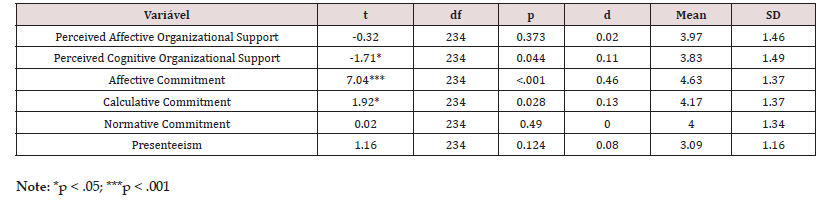

The position of the responses given by the participants in this study was tested using Student’s T-tests for a sample. The results indicate that only the perception of cognitive organizational support, affective commitment, and calculative commitment differ significantly from the midpoint of the scale (4) (Table 1). The participants in this study revealed a low perception of cognitive organizational support but a high level of affective and calculative commitment (Table 1).

Association Between the Variables Under Study

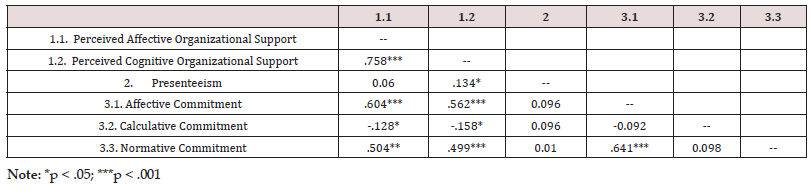

The association between the variables under study was tested using Pearson correlations. The perception of affective organizational support is positively and significantly correlated with both affective and normative commitment but negatively and significantly correlated with calculative commitment (Table 2). The perception of cognitive organizational support is positively and significantly correlated with presenteeism, affective commitment and normative commitment but negatively and significantly correlated with calculative commitment (Table 2).

Hypotheses

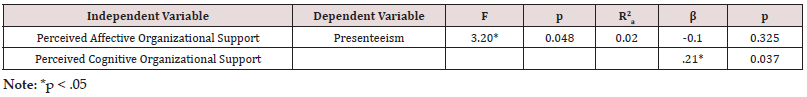

The hypotheses formulated in this study were tested using multiple linear regressions. The results indicate that only the perception of cognitive organizational support has a positive and significant effect on presenteeism (Table 3). The model explains 2% of the variability in presenteeism and is statistically significant (Table 3).

This hypothesis was partially confirmed.

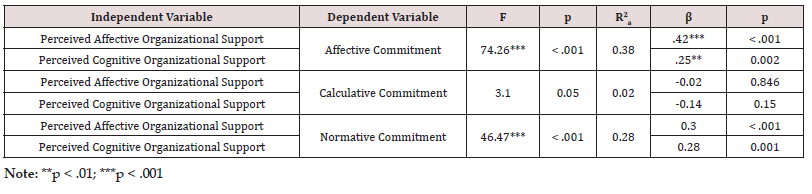

The results indicate that the perception of affective organizational support and the perception of cognitive organizational support have a positive and significant effect on affective commitment (Table 4). The model explains 38% of the variability in affective commitment and is statistically significant (Table 4). Neither affective nor cognitive organizational support has a significant effect on calculative commitment (Table 4).

Perceived affective organizational support and perceived cognitive organizational support have a positive and significant effect on normative commitment (Table 4). The model explains 28% of the variability in normative commitment and is statistically significant (Table 4).

This hypothesis was partially confirmed.

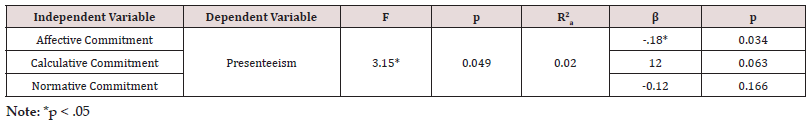

The results indicate that only affective commitment has a negative and significant effect on presenteeism (Table 5). The model explains 2% of the variability in presenteeism and is statistically significant (Table 5). This hypothesis was partially confirmed.

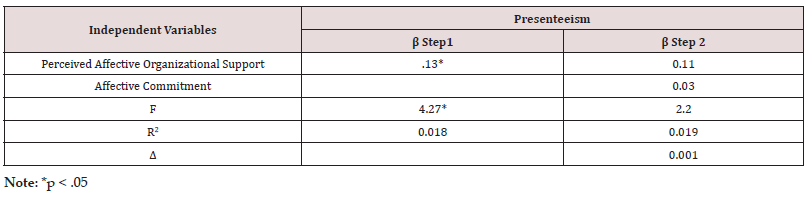

As this hypothesis presupposed a mediating effect, the procedures according to Baron and Kenny [26] were followed. Due to the results obtained in the previous hypotheses, only the mediating effect of affective commitment on the relationship between cognitive organizational support and presenteeism was tested.

The results indicate that affective commitment does not have a mediating effect on the relationship between perceived cognitive organizational support and presenteeism (Table 6). This hypothesis was not supported.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and presenteeism, as well as to assess whether this relationship is mediated by organizational commitment. The results obtained provide valuable insights into the dynamics between these variables and their implications for human resource management in local authorities in Portugal. The first hypothesis, which posits that perceived organizational support negatively affects presenteeism, was only partially confirmed. The results indicated that cognitive perceived organizational support has a positive and significant effect on presenteeism, while affective perception did not show a statistically significant relationship. These findings are consistent with the literature, which suggests that positive POS can contribute to a healthier work environment that is less prone to presenteeism [6]. Employees who feel that the organization values their contributions and cares about their emotional well-being tend to develop greater loyalty and are, therefore, more willing to take care of their health.

The second hypothesis, which predicted a positive effect of POS on organizational commitment, was partially confirmed. The perception of affective and cognitive organizational support was found to have a significant effect on affective and normative commitment but not on calculative commitment. This distinction is relevant since affective commitment, which relates to employees’ emotional identification with the organization, is a strong predictor of positive behaviours in the workplace [3]. However, the absence of a significant effect of OSP on calculative commitment suggests that employees’ motivation to remain in the organization may not be directly linked to their perception of organizational support. This finding suggests that external factors, such as career opportunities or working conditions, also play a significant role in employees’ decisions to remain in their current jobs. The third hypothesis, which assessed whether organizational commitment had a negative effect on presenteeism, was confirmed only for affective commitment. Employees with high affective commitment tend to prioritize their health and well-being, resulting in fewer cases of presenteeism. This result aligns with previous research linking organizational commitment to reduced presenteeism, reinforcing the notion that engaged employees are more likely to prioritize their health [4].

Finally, the fourth hypothesis, which sought to establish organizational commitment as a mediator between POS and presenteeism, was not confirmed. The results showed that affective commitment does not have a significant mediating effect on the relationship between cognitive organizational support and presenteeism. This result suggests that, although a relationship exists between the variables, affective commitment alone may not be sufficient to explain the impact of POS on presenteeism. This may indicate the need to explore other mediators or moderators that may influence this relationship.

Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of the study is its cross-sectional nature, which prevents the determination of causal relationships between variables. In addition, the sample consisted only of employees of local authorities in Portugal, which may limit the generalization of the results to other organizational or geographical contexts. The use of a non-probability sampling method may also introduce bias, affecting the representativeness of the sample. Future research could explore the relationship between POS and presenteeism in different organizational and cultural contexts, as well as investigate other possible mediators or moderators, such as intrinsic motivation or organizational culture. Additionally, longitudinal studies could provide a clearer understanding of how these relationships evolve over time and under various circumstances. The inclusion of additional variables, such as mental health and perceived stress, could also enrich the understanding of the complexity of these dynamics.

Theoretical Implications

a. Contribution to the Theory of Organizational Support Perception: This study reinforces the importance of organizational support perception (OSP) as a fundamental construct in organizational psychology. By demonstrating that cognitive OSP has a significant impact on presenteeism, the research contributes to the existing literature, suggesting that the way employees perceive the support available to them can directly influence their behavior at work.

b. Interrelationship between Variables: The results obtained highlight the complexity of the relationships among OSP, organizational commitment, and presenteeism. The evidence that affective commitment, although not meditating, reduces presenteeism suggests that employees’ emotional identification with the organization is a relevant factor that deserves further theoretical attention. This interconnection may lead to further investigations into how different types of commitment relate to work behavior.

c. Challenges for Organizational Commitment Theory: The lack of a mediating effect of affective commitment in the relationship between POS and presenteeism challenges some assumptions of organizational commitment theory. This suggests the need to review and expand existing theoretical models to include contextual variables that may influence these relationships.

Practical Implications

a. Development of Organizational Support Policies: Organizations, especially local authorities, should consider implementing policies that promote positive POS. This may include programs that emphasize not only emotional support but also structural resources, such as training and professional development, that help employees feel valued and recognized.

b. Promotion of Affective Commitment: The findings suggest that organizations should focus on strategies that increase employees’ affective commitment. This can be achieved through initiatives that promote employees’ identification with the organization’s values and objectives, such as recognition and reward programs, as well as opportunities to participate in organizational decisions.

c. Creating a Healthy Work Environment: The practical implications of this study underscore the importance of fostering a work environment that prioritizes employee health and well-being. Implementing policies that encourage open communication about mental health, as well as flexibility at work, can help reduce presenteeism and promote a favorable organizational climate.

d. Training Leaders and Managers: Training leaders and managers in emotional and cognitive support skills can be crucial to improving POS within organizations. Empowering leaders to recognize and address employee needs can contribute significantly to building a more inclusive and productive work environment.

e. Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation: Organizations should implement systems for the continuous monitoring and evaluation of perceptions of organizational support and presenteeism. This will enable a swift response to potential problems, contributing to the continuous improvement of the work environment [27,28].

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and presenteeism and to explore whether organizational commitment acts as a mediator in this relationship. Based on the hypotheses formulated, the interactions between these variables were analyzed in the context of local authorities in Portugal. The main findings indicated that cognitive OSP has a positive influence on presenteeism, while affective OSP did not show a significant relationship. Furthermore, affective commitment was identified as a factor that reduces presenteeism; however, it did not act as a mediator between OSP and presenteeism. These results suggest that, although organizational support is crucial for employee well-being, the perception of emotional support is not sufficient to mitigate presenteeism behaviours, highlighting the importance of structural factors.

This study contributes to existing literature by offering a deeper understanding of the dynamics between OSP, organizational commitment and presenteeism, especially in a specific organizational context. The findings highlight the need for organizational support that goes beyond emotional support, incorporating structural aspects that promote a healthy and productive work environment. However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of this study, including its cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to infer causal relationships, and the sample being limited to local government employees in Portugal, which may affect the generalizability of the results. For future research, we recommend conducting longitudinal studies to clarify the evolution of relationships between these variables over time. Additionally, investigating other mediators or moderators, such as intrinsic motivation and perceived stress, could further enrich our understanding of the dynamics in question. The inclusion of different organizational and cultural contexts is also essential to broaden the practical and theoretical implications of this topic.

In summary, this study not only confirms the importance of POS and organizational commitment in combating presenteeism but also opens avenues for further research that can contribute to healthier and more efficient work environments. The theoretical and practical implications derived from this study highlight the importance of understanding the dynamics between perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and presenteeism. Organizations that invest in promoting a healthy work environment and strengthening employee commitment will not only benefit their employees but also achieve better organizational results in the long term.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- Schein EH (2010) Organizational Culture and Leadership (4th ed.) Jossey-Bass.

- Johns G (2010) Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(4): 519-542.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1991) A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1): 61-89.

- Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Halbesleben JRB (2015) Productive and counterproductive job crafting: A daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4): 457–469.

- Karanika-Murray M, Biron C (2020) The health-performance framework of presenteeism: Towards understanding an adaptive behaviour. Human Relations, 73(2): 242–261.

- Rhoades L, Eisenberger R (2002) Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4): 698-714.

- Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D (2001) Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1): 500-507.

- Hemp P (2004) Presenteeism: At work-But out of it. Harvard Business Review, 82(10): 49-58.

- Aronsson G, Gustafsson K, Dallner M (2000) Sick but yet at work. An empirical study of sickness presenteeism. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 54(7): 502-509.

- Kivimäki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, Fransson EI, Heikkilä K, et al. (2005) Job strain and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. European Heart Journal, 26 (15): 1434-1442.

- Arslaner E, Boylu Y (2017) Perceived organizational support, work-family/family-work conflict and presenteeism in hotel industry. Tourism Review, 72(2): 171-183.

- Sahin D, Aydin S (2021) The relationship between Presenteeism, Perceived Organizational Support, Climate of Fear And Vigor. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University SBE Magazine, 11(1): 30-43.

- Becker HS (1960) Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66(1): 32-40.

- Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L (2002) Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61: 20-52.

- González-Romá V, Peiró JM, Erez M (2006) The role of leadership in the development of organizational commitment: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5): 631-648.

- Silva R, Dias A, Pereira L, Costa RL, Rui Gonçalves (2022) Exploring the Direct and Indirect Influence of Perceived Organizational Support on Affective Organizational Commitment. Social Sciences 11: 406.

- Kim KY, Eisenberger R, Baik K (2016) Perceived organizational support and affective organizational commitment: Moderating influence of perceived organizational competence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(4): 558–583.

- Fsafy-Godineau F, Carassus D (2021) The influence of perceived organizational support and organizational commitment on absenteeism in the local public sector. Gestion & Management Public Journal, 9(2): 79-97.

- Trochim W (2000) The Research Method Knowledge Base. 2nd Edition. Atomic Dog Publishing.

- Eisenberger R, Cummings J, Armeli S, Lynch P (1997) Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. The Journal of applied psychology, 82(5): 812–820.

- Ozminkowski RJ, Goetzel RZ, Chang S, Long S (2004) The application of two health and productivity instruments at a large employer. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 46: 635-648.

- Ferreira A, Martinez L, Sousa LM, Cunha JV (2010) Translation and validation into Portuguese of the WLQ-8 and SPS-6 presenteeism scales. Avaliação Psicológica, 9(2): 253-266.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1997) Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Sage Publications.

- Nascimento JL, Lopes A, e Salgueiro MF (2008) Study on the validation of Meyer and Allen's "Organizational Commitment Model" for the Portuguese context. Organizational Behavior and Management,14 (1): 115-133.

- Finney SJ, DiStefano C (2013) Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.): Structural equation modeling: A second course (2nd ed) IAP Information Age Publishing, pp. 439–492.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6): 1173-1182.

- Bryman A, Cramer D (2003) Data analysis in social sciences. Introduction to techniques using SPSS for Windows (3rd ed.) Celta.

- Santos JV, Gonçalves G (2010) Contribution to the Portuguese adaptation of the Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa (1986) Organizational Support Perception Scale Psychology Laboratory 8: 213–23.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...