Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Review ArticleOpen Access

Supporting Patients Who are Ready to Stop Antidepressants-Pressing Need for More Research in Long Term Use Volume 3 - Issue 3

Amrit Takhar1*, Stephen Sutton2 and Michael Morgan Curran3

- 1General Practioner, Wansford surgery, Wansford, UK

- 2Professor of Behavioural Science and Director of Research, Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, UK

- 3Head of Commercial & Clinical Development at MyCognition Steeple Morden, Cambridge , UK

Received: December 12, 2019; Published: January 07, 2020

Corresponding author: Amrit Takhar, Wansford surgery, Wansford,Peterborough PE8 6PL, UK

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2020.03.000162

Introduction

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

A substantial proportion of primary care patients are long-term users of antidepressant medication. Antidepressants are often started when patients have episodes of mild to moderate depression or mixed anxiety and depression. After a prolonged course of 2 years many patients may be ready to stop antidepressants but data shows that large numbers struggle to stop. The continuation of antidepressants long term leaves users prone to adverse effects and interactions with other medication especially in the elderly. There is limited research in the longer term use of antidepressants and in interventions to help users to stop. In an analysis of routine data from 78 urban general practices in Scotland, 8.6% (33,312/388,656) of all registered patients were prescribed an antidepressant, and 47.1% of these were defined as long-term users of >= 2 years [1]. In a recent audit of records in one practice in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, UK 10% of patients had been using antidepressants for more than 12 months. Many of these long-term users may no longer obtain any benefits from the medication and may experience harmful consequences associated with long-term use; continued use of medication that is no longer needed is also an unnecessary cost to health services Current UK guidance recommends that patients are gradually ‘weaned off’ medication under supervision of their GP [2-6]. However the best ways of weaning off has not been formally specified in terms of the schedule and how patients should be supported in ways that could be widely used in primary care. Until recently there was limited acceptance by psychiatrists that patients may find it very difficult to stop antidepressants due to the severity of withdrawal symptoms [7,8].

Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

It is well established that there is the large number of long-term users of antidepressants (8-10% of all adult patients) and de-prescribing interventions are not well described or studied. It is common to note that the pharmaceutical industry undertakes extensive research into starting medications but then rarely undertakes similar research in how drugs can be stopped especially in primary care. The original research into starting medication is usually carried out in hospital and outpatient settings but especially in health systems such as the UK the prescribing and monitoring of antidepressants is carried out by general practitoners. We are aware of only one trial of a de-prescribing intervention for potentially inappropriate or unnecessary long-term use of antidepressants in primary care [9-13]; this Dutch study had disappointing findings. However, there is suggestive evidence that using a cognitive training app as part of a structured de-prescribing intervention may help patients to discontinue antidepressant use.

Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

Current NICE guidance [14] states: 11.8.7.2 Advise people with depression who are taking antidepressants that discontinuation symptoms may occur on stopping, missing doses or, occasionally, on reducing the dose of the drug. Explain that symptoms are usually mild and self-limiting over about 1 week, but can be severe, particularly if the drug is stopped abruptly. 11.8.7.3 When stopping an antidepressant, gradually reduce the dose, normally over a 4-week period, although some people may require longer periods, particularly with drugs with a shorter half-life (such as paroxetine and venlafaxine). This is not required with fluoxetine because of its long half-life: 11.8.7.4 Inform the person that they should seek advice from their practitioner.

If they experience significant discontinuation symptoms. If discontinuation symptoms occur:

a) Monitor symptoms and reassure the person if symptoms

are mild.

b) Consider reintroducing the original antidepressant at

the dose that was effective (or another antidepressant with a

longer half-life from the same class) if symptoms are severe,

and reduce the dose gradually while monitoring symptoms.

The supporting evidence for these recommendations is presented in the guideline [15]. Based on these recommendations, we propose a need for research to formally specify the schedule and content of an intervention that could be widely applied in primary care. The remainder of this section reviews the evidence supporting the use of a cognitive training app as part of a de-prescribing intervention for long-term antidepressant users. Cognitive deficits are major components of psychiatric disorders, and a principal mediator of psychosocial impairment, with negative impact on quality of life, social and work interactions and performance. Cognitive impairment represents a core feature of depression that cannot be considered an epiphenomenon that is entirely secondary to symptoms of low mood and that may be a valuable target for interventions. Among the components of cognitive impairment, Executive Function has the greater impact and the greatest role in linking Major Depression Disorder (MDD) and psychosocial dysfunction, followed by Working Memory, Attention and Processing Speed. Key deficits in Executive function and Attention persist when the depressive symptoms have remitted [16-18].

Impaired cognitive functioning has been linked with poor response to antidepressant treatment [19,20]. However, the potential clinical relevance of cognitive deficits in depression also depends upon their impact on psychosocial functioning. Impaired psychosocial functioning is a core feature of depression. It persists in up to 60% of individuals with depression even after mood symptoms of depression have remitted, indicating that severity of depressive symptoms cannot fully account for impaired functional ability. One possible explanation is that persisting cognitive impairments may contribute to poor quality of life and psychosocial functioning in patients whose depressive symptoms have remitted. In support of this, psychosocial functioning has been shown to be associated with performance on measures of attention, executive function, paired associates learning and visuo-spatial ability in depression. Importantly, the association between cognitive deficits and poor psychosocial functioning has been shown to remain significant even when considering residual, subclinical depressive symptoms [19]. Remediation of cognitive impairment and alleviation of depressive symptoms may both be involved in improving psychosocial functioning in depression. Cognitive impairment in depression is clinically relevant and may be a valuable target for intervention [11].

Based on this evidence, interventions targeting the improvement of cognitive functioning in patients with prolonged used of antidepressants:

a) Address cognitive deficits responsible for psychosocial

dysfunction which may persist after the mood symptoms have

remitted.

b) Build psychological resilience towards a relapse of

symptoms.

c) Be a valid additional or alternative intervention during

the tapering period.

Research shows that cognitive remediation programmes are effective in improving cognition and global functioning in psychiatric patients [20,21]. The MyCognition app which was designed by experts in neuropsychology and serious gaming and has been validated through five years of research with over 18,000 user cases. We believe this could be used to support deprescribing antidepressants along with other supportive techniques and therapies.

MyCognition is unique in combining cognitive assessment (MyCQ) and a cognitive training game (‘AquaSnap’) to automatically provide the user with an individual training regimen personalised on their cognitive assessment scores:

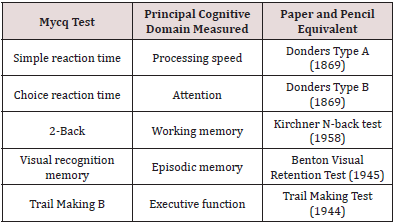

a) The MyCQ cognitive assessment consists of 5 subtests that

measure five domains of cognition (processing speed, attention,

memory, working memory and executive function) within 15

minutes. Preliminary results on its validity are positive ([22];

see Table 1 in the Appendix).

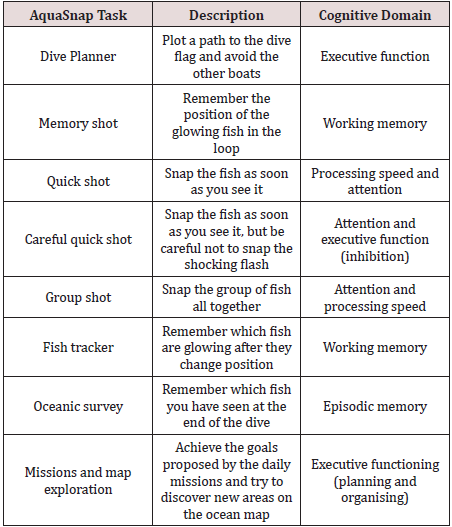

b) AquaSnap is a high definition interactive platform game

which aims to offer personalised training of the cognitive

domains of processing speed, attention, episodic memory,

working memory and executive functioning.

Algorithms set to individuals MyCQ scores drive training loops which improve each domain. In the game, users explore the ocean and complete missions. While diving the player takes photographs of fish. Taking the best photographs and completing missions will give the player experience and coins, which can be used to discover new diving areas where players can encounter more unique fish. To train each cognitive domain, loops were developed to represent different ways to photograph fish. Some loops train more than one domain. A series of loops are combined into an underwater dive. The game gets more difficult as the player proceeds further into the ocean and unlocks new areas. (Table 2) in the Appendix shows an overview of the tasks and cognitive domains. A randomised controlled trial conducted at the Academic Medical Centre (AMC), Amsterdam, and involving 87 mixed psychiatric patients (including Depression, Schizophrenia and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder) reported a positive dose response to AquaSnap, with significant improvements in global cognition and working memory and trends for improved global cognition and executive functioning among patients who spent longer playing the game (Domen et al., under review). Results of an interim analysis are published at [6,8,20,1,8]. Cognitive remediation in psychiatric patients with an online cognitive game and assessment tool.

The MyCognition app is approved by ORCHA, the world’s leading health app evaluation and advisor organisation [https://appfinder.orcha.co.uk/review/137131/], and it is currently the only app listed in the ‘Mental Health’ section of the NHS Digital App library targeting cognitive functioning, providing an alternative to standard approaches [https://www.nhs.uk/apps-library/mycognition-home/]. MyCognition is regulated by the MHRA (Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency) and CE marked as a Class 1A medical device.In an independent review undertaken for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the following comparison report was received:“Why they’re unique: The rigor in My Cognition’s combined assessment-intervention approach is a true differentiator in the field. While we’ve seen a few other products that try to do both, MyCognition is the most comprehensive. Further, their approach to engage users in training through a gamified approach offers a sticky solution to addressing areas with the highest potential for growth. Given the choice, most of us would rather capitalize on our own existing strengths but excelling in AquaSnap requires the user to address the domain with the greatest potential for improvement.”Catherine May, Strategist at International Futures.

Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

We believe this evidence supports the possibility of undertaking research on the feasibility and acceptability of two versions of an intervention to help primary care patients on long-term antidepressant use discontinue their medication if they wish to do so: a structured series of brief consultations with the GP with and without the offer to use a cognitive training app. The findings would inform a subsequent full trial of the effectiveness and costeffectiveness of one or both interventions Aims of the proposed research to develop a structured de-prescribing intervention suitable for primary care into which an existing cognitive training app could easily be incorporated. to assess the feasibility, acceptability, cost and potential efficacy of two versions of the intervention (structured series of brief consultations with the GP with and without the offer to use a cognitive training app) to assess the feasibility of conducting a full effectiveness trial with economic evaluation.

Research questions

a) Are the interventions feasible and acceptable?

b) Is it feasible to conduct a full effectiveness trial with

economic evaluation?

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

It is well established that we should patients in the design of research so we convened a local PPI group, and held an initial meeting lasting over 2 hours with eight patients on long-term antidepressants recruited from Wansford surgery, Peterborough, on 13th June 2019. Jon Scales from the Eastern region Research Design Service facilitated this meeting and explained the remit and role of the PPI group, Dr Amrit Takhar outlined the clinical issue and gave an overview of the research project, and Michael Morgan Curran from MyCognition explained the App. Patient participants were very engaged, keen to share their own very varied experiences, and voiced a number of suggestions. They confirmed that this was an important topic and supported the idea of a study to develop and evaluate an intervention to help wean patients off antidepressant medication. However, they noted that patients who are stable on current therapy may not be keen to discontinue anti-depressant medication. The PPI participants are keen to be kept informed about the development of the project. Most of them expressed interest in keeping involved through the lifetime of the research project and are keen to meet again if the proposed research is developed further.

They suggested that the MyCognition app could be discussed in a future meeting and that a 1-year licence could be offered as a thank you for participation and also as an opportunity to obtain informal feedback. They also suggested that evening meetings would be easier for them to take part in and the research team agreed to try to facilitate this. After the meeting, PPI participants were emailed a draft of the Plain English Summary and asked for their comments. Several participants suggested clarifications which we incorporated in research design being developed If the proposed research in this paper is developed these PPI participants will be asked to comment at different stages of the project, including the development of the interventions, the design of the feasibility trial, the recruitment documents and procedures, the measures to be used and the meaning of the findings. We would also ask the patient group to help with dissemination.

Conclusion

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

This discussion paper outlines the case for more practical and pragmatic research on the topic of supporting patients to able to stop long term antidepressants after one to two years of therapy. This research needs to take place in primary care settings where these drugs are commonly prescribed. We have described how this is a major public health issue where millions of patients are taking long term antidepressants but are not routinely supported with evidencebased strategies to help wean off medication. We also outline the case for using a novel cognition app in supporting patients if stopping antidepressants. A feasibility study to test this hypothesis is recommended.

References

- Introduction

- Why we Need More Research into How Patients Can Be Supported in Stopping Antidepressants

- Review of Existing Evidence of Discontinuing Antidepressants

- Potential for Research on Deprescribing Antidepressants with or without Cognitive Training

- Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

- Conclusion

- References

- Charmaz K (2006)Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis.

- Domen A, Jaspers M, Denys D, Nieman D (2009) A new cognitive training game for psychiatric patients: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Under review 7(9): 1-10.

- Domen AC, Van De Weijer SCF, Jaspers MW, Denys D, Nieman DH (2019) The validation of as new online cognitive assessment tool: The MyCognition Quotient. International Journal of Research Methods in Psychiatric Research 28(3): e1775.

- Eveleigh R, Muskens E, Lucassen P, Verhaak P, Spijker J, et al. (2017)Withdrawal of unnecessary antidepressant medication: a randomised controlled trial. BJGP Open1(4): 1-45.

- Farmer A, Hardeman W, Hughes D, Prevost AT, Kim Y, et al. (2012) An explanatory randomised controlled trial of a nurse-led consultation-based intervention to support patients with adherence to taking glucose lowering medication for type 2 diabetes. BMC Family Practice 13: 1-30.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, et al. (2011) Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research 20(10):1727-1736.

- Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, DavisConway S (2006) Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research 145(1):39-48.

- Johnson CF, MacDonald HJ, Atkinson P, Buchanan AI, Downes N, et al. (2012) Reviewing long-term antidepressants can reduce drug burden.British Journal of General Practice 62(604):e744-9.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16(9):606-613.

- McIntyre R S, Cha DS, Soczynska JK, Woldeyohannes HO, Gallaugher LA, et al. (2013) Cognitive deficits and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: determinants, substrates, and treatment interventions. Depression and Anxiety 30(6):515-527.

- Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brüne M, Bullmore ET, Carter C S, et al. (2012) Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 11(2):141-168.

- Motter JN, Pimontel MA, Rindskopf D, Devanand DP, Doraiswamy PM, et al. (2016) Computerized cognitive training and functional recovery in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders189: 184-191.

- Naughton F, Prevost AT, Gilbert H, Sutton S (2012) Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluation of a Tailored Leaflet and SMS Text Message Self-help Intervention for Pregnant Smokers (MiQuit). Nicotine and Tobacco Research14(5):569-577.

- NICE(2018) The NICE guideline on the treatment and management of depression in adults. Updated edition.

- Nieman DH, Domen AC, Kumar R, Harrison J, De Haan L, et al. (2005) Cognitive remediation in psychiatric patients with an online cognitive game and assessment tool.European Neuropsychopharmacology25: S344-S345.

- Potter GG, Kittinger JD, Wagner HR, Steffens DC, Krishnan KRR (2004) Prefrontal neuropsychological predictors of treatment remission in late-life depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 29(12):2266-2271.

- Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese (2014) Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidencebased, patientcentred deprescribing process. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 78(4):738-747.

- Ritchie J, Spencer J (2002) Qualitative data analysis for Applied policy research. In Huberman AM, Miles MB (Eds.) The qualitative researcher’s companion: classic and contemporary readings pp: 305-329.

- Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD (2014) Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine44(10):2029-2040.

- Story TJ, Potter GG, Attix DK, WelshBohmer KA (2008) Neurocognitive correlates of response to treatment in late-life depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16(9):752-759.

- Van De Weijet SCF, Duits AA, Bloem BR, Kessels RP, Jansen JFA, et al. (2016) The Parkin’Play study: protocol of a phase II randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of a health game on cognition in Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurology 16(1): 200-209.

- Wilson E, Lader M (2015) A review of the management of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 5(6):357-368.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...