Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Sexual Exploitation of Children, Hardships and Resilience Building: Learning from NGO Good Practices in Uganda Volume 6 - Issue 2

Rogers Kasirye*, Paul Bukuluki and Eddy J Walakira

- Department of Social Work and Social Administration, Makerere University, Uganda

Received:February 05, 2022; Published:February 24, 2022

Corresponding author: Rogers Kasirye, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, Makerere University, Uganda

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.06.000235

Abstract

Introduction

Childhood experiences should be able to bring joy and when children have a positive childhood experience and this allows for improved wellbeing in adulthood [1] and future health outcomes. There are personal vulnerabilities associated and may lead to children’s entry into prostitution, such as being in contact with someone involved in SEC, lack of job skills and limited job opportunities. Many interventions that help survivors exit sexual exploitation have been documented, but fewer are explicit in explaining resilience building and good practices in Uganda setting. This information once collected will help to share the good practices that can be utilised to prevent and improve lives of survivors caught in sexual exploitation.

Methodology

Study design: The study employed an exploratory design, employing qualitative methods to gather information to describe the phenomena. Data was obtained from multiple sources including, NGO staff, Child survivors of SEC and other gatekeepers. Two child friendly tools were used in the study, the Venn diagram and River of life to collect more information from child survivors in a participatory and interactive way. The data collected from the study participants was analysed using a method of thematic analysis to find ways of working with data.

Findings

Despite the small numbers of survivors covered from NGOs, children who had faced many hardships and very traumatising experiences. Several good practices amongst the three NGOs were noted including a breadth of psycho-social and economic empowerment interventions. Complemented and involved survivors, parents and tapping community resources.

Discussion

Findings have showed that resilience building activities don’t need to be narrowly fixed, but can be broad; There is need to use resiliency delivery frameworks that goes beyond the psycho-social measurements that are common in the western world, to include social capital aspects, physical activity and economic empowerment.

Conclusion

Hardships faced by children in homes, early sexual activities, alcohol and drug use amongst peers are problematic issues that need early interventions.

Keywords: Risk Factors; Violence; Sexual Exploitation Children

Introduction

Childhood experiences should be able to bring joy and when children have a positive childhood experience and this allows for improved wellbeing in adulthood [1] and future health outcomes. Generally, children are increasingly engaged in underground economies [2] such as trafficking, pornography, prostitution, stripping or online grooming [3,4]. Globally it as acknowledged that children cannot consent to engage and trade in sexual activities whether for commercial or other gains of sex coercion, SEC constitute a crime in international law under article. 3 of the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (2000) [5]. Most jurisprudence now considers sexual involvement with minors a crime and children regarded as innocent victims [2]. Despite the global estimate of children under sexual exploitation reducing from 1.8 million in 2004 to 1.0 million. Women and Girls account for 99 percent of all victims of forced sexual exploitation. ILO continue to report that 1 million of the victims of forced sexual exploitation, 21 percent children under 18 years of age. In Uganda studies by ECPAT/ [4,6] point out that the number of children affected had jumped to 18,000 children in 2011 from 12,000 in 2004 in urban centres and across the country. Sexual exploitation of minors violates the Children’s Rights Convention 1989 especially article 34, 39 and Article 44. Evidence reveals that sex exploitation of children disproportionately affects more girls than boys [4]. The risks factors that expose girls to sexual exploitation have been identified to include among others poverty, early school dropout, and child abuse, violence, substance use and effects of HIV/AIDS infections hence survivors get easily manipulated [7]. Orphan hood and subsequent trafficking of children leads to disruption of normal living, loss of hope and getting trapped in SEC and this paves way for extreme poverty and compromised quality making their future uncertain [8].

There are personal vulnerabilities associated and may lead to children’s entry into prostitution, such as being in contact with someone involved in SEC, lack of job skills and limited job opportunities. Studies by Clawson, Dutch and Williamson (2008) and Lederer (2014) show that victims of SEC are at increased risk of psychosocial problems including violence, substance abuse, trauma, suicide and variety of physical and mental health needs. Children facing SEC need help to recover positively [9] because of negative consequences of SEC which requires a holistic approach intervention. Similarly, availability of emotional support from parents and other adults strengthens ability to recover. The hardships they encounter affect health and emotional outcomes survivors face compared to other child vulnerabilities [10]. SEC is harmful in multiple ways which harm the child, physically and psychologically making them defenceless and predisposed. The prolonged grief leads to persistent anger, self-blame making them victims of violence, substance abuse and poor family relationship. Children suffer additional stress associated with shame, secrecy and fear of disclosure of their past which triggers negative emotions of depression, isolation and possibility of suicide [10,11]. Unaddressed trauma and other hardships can spill over in adulthood hence interfering with normal functioning of survivors.

There are personal vulnerabilities associated and may lead to children’s entry into prostitution, such as being in contact with someone involved in SEC, lack of job skills and limited job opportunities. Studies by Clawson, Dutch and Williamson (2008) and Lederer (2014) show that victims of SEC are at increased risk of psychosocial problems including violence, substance abuse, trauma, suicide and variety of physical and mental health needs. Children facing SEC need help to recover positively [9] because of negative consequences of SEC which requires a holistic approach intervention. Similarly, availability of emotional support from parents and other adults strengthens ability to recover. The hardships they encounter affect health and emotional outcomes survivors face compared to other child vulnerabilities [10]. SEC is harmful in multiple ways which harm the child, physically and psychologically making them defenceless and predisposed. The prolonged grief leads to persistent anger, self-blame making them victims of violence, substance abuse and poor family relationship. Children suffer additional stress associated with shame, secrecy and fear of disclosure of their past which triggers negative emotions of depression, isolation and possibility of suicide [10,11]. Unaddressed trauma and other hardships can spill over in adulthood hence interfering with normal functioning of survivors.

Many interventions that help survivors exit sexual exploitation have been documented, but fewer are explicit in explaining resilience and good practices in Uganda setting. In Social Work, when we examine how society cares for its children, especially disadvantaged children, we are peering into the heart of the nation. Most work written about SEC has concentrated in listing triggers, improving legislation and prosecution, how to prevent entry, vocational skills programs and many policy approaches are largely amongst adult survivors. How do NGOs navigate and help children recover from SEC with many social hardships that they face in addition to having to make a living as prostitutes? The triggers, motives and challenges they face, as well as the health seeking behaviour and the many stressors they go through a gap this study wanted to partially fill.

Methodology

Study Design

The study employed an exploratory design, employing qualitative methods to gather information to describe the phenomena. Data was obtained from multiple sources including, NGO staff, Child survivors of SEC and other gatekeepers.

Area of study, setting and sampling of participants

The study was based in Kampala City, Uganda. The Three NGOs were purposely selected from available literature in the Ministry of Internal Affairs about NGO actors in the prevention and rehabilitation of victims of trafficking and sexual exploitation. Other study participants such as survivors who had never received NGO rehabilitation services were recruited with help of peers, conversant with former survivors of SEC.

The agencies that were selected varied in size, numbers of survivors assisted, as indicated below:

a) Set Her Free (SHF), Kawempe: SHF equips Uganda’s most vulnerable girls and young women with knowledge and skills that they need to lead self-sustained lives. Interventions include Sexual and Reproductive Health education, Temporary housing, Counselling, Vocational skills and Clinical Referrals for each beneficiary.

b) Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL), This started way back in 1993 and serves six (6) Divisions of Kampala, Wakiso and Mukono, tackling child trafficking, homelessness, drug abuse, alcoholism, child sexual exploitation, HIV/AIDS, online child pornography, psycho-social support and vocational skills as well as economic empowerment.

c) Somero Uganda, Kawempe: Somero operates a youth community center in the slums of Kawempe Division implementing projects on HIV/AIDS Prevention, Care and Support; Sexual Reproductive Health (SRH); Drug abuse prevention; Counselling and Career guidance among others.

Study Population, Participants, Recruitment and Study Sample

Two key primary study populations were identified to be able to respond to the study objectives. This comprised of the survivors and beneficiaries of the resilience building activities. The other were the NGO staffs and other gatekeepers in facilitating resilience building activities such as, parents, local leaders, public officials and key stakeholders in the community. The survey excluded children who were at risk of SEC at the time of the study. Other sources of information relating to resilience enhancement for child survivors of SEC included NGO reports, documents and well as the Internet and library sources. The age of survivors in the study population ranged between 14-17 years, mainly from the Central region districts of Uganda. Using purposive sampling, ten children were selected from each NGO, giving a total of 30 children plus 6 who had left the NGO felicities and living on their own. The study team included six (6) former CSE survivors who never went through any NGOs but had recovered from CSE so as to get more diverse views of resilience building.

Data collection methods

Two child friendly tools were used in the study; the Venn diagram and River of life to collect more information from child survivors in a participatory and interactive way. These were used to avoid harm and traumatization given the sensitivity of the study; yet there was need to get the highest responses.

Venn diagram

It is a type of graphic organizer expounded by John Venn in 1891. Graphic organizers are a way of visually organizing complex relationships which allow abstract ideas to be more visible. The child survivors were able to express their ideas and the nature of traumatic experience they had.

River of life the river of life is a type of sketch drawing that aimed to help survivors of SEC to show circumstances, individuals and events which were particularly significant in their lives until the present day. Fisher & White (2001) observes that the “River of life is a visual narrative method that helps people tell stories of the past, present and future. Individuals can use this method to introduce themselves in a fun and descriptive way; a group can use it to understand and reflect on the past and imagine the future of a project; and it can be used to build a shared view compiled of different and perhaps differing perspectives. River of Life focuses on drawing rather than text, making it useful in groups that do not share a language. When used in a group, it is an active method, good for engaging people”.

During data collection from child survivors, we additionally did a stakeholder analysis to map out places of risks, upsetting experiences and resources at the NGO rehabilitation centre, home, community and other resources. Survivors recorded the individuals they interact with, and their activities to reveal the potential of their influence on them. During data collection, we used small numbers of child participants to allow maximum interaction, discussing their cultural norms as well as bringing in some element of fun. This ensured that interviews were conducted in a friendly environment with no interference but enabled children to feel safe, confident, emotionally secure without any secondary trauma and reduction in anxiety [14]. It also allowed them to reflect on the trauma they went through and open up if it had desensitisation effect and here how other survivors (therapeutically) managed to overcome it during the FGD discussion. The interviews were psychologically empowering (therapeutic nature) and unearthed other stressful issues which survivors had experienced.

The interview method enabled the participants to map their stories on the river of life drawing as elaborated below. We used the tool to retain the participants’ narrative in their natural form and the focus is on members’ perspective and experience. The researchers collected information from child survivors in a participatory way to allow maximum interaction, based on their age, cultural norms, and an element of fun. This ensured that interviews were conducted in a friendly environment without any interference (i.e. felt confident, physically safe, free from harm, emotionally secure). The study later engaged survivors using a flip chart, paper and markers to plot on the map their rich River of life history about SEC. This was intended to prepare them to express their feelings and also be heard as they shared their stories about their experiences that had shaped them in different situations.

Survivors were asked to reflect on their experiences and create a diagrammatic sketch drawing in the River of life tool of their SEC experience the banks, tributaries and rapids, as well as what happened at that juncture of life. Enough time was given for everyone to freely share and explain their experiences. The River of life tool avoids a normal face to face interview where some of the questions are sensitive and could invoke past traumatic experience. The tool is also better in minimizing too many details which can be problematic. Most information shared by study participants was descriptive (what had happened in their lives) and explanatory (how and why it was happening). The data revealed varying experiences and circumstances that helped to explain in detail a few but particular SEC survivors’ situation. One limitation

encountered with the river of life method of data collection was that some child survivors could not express themselves or write in English. Researchers used local language and translated the information for clarity. To address causes and risk factor of SEC requires an understanding of the status of the problem and of complex risk factors and vulnerabilities [2]. A situation which can easily be derived from the case studies using the child friendly tools like Venn and River of life.

Data Analysis

The data collected from the study participants was analysed using a method of thematic analysis to find ways of working with data. The survey identified all key issues based on Franchino-Olsen [2] discussion of risk factors common in the western world with a special focus on USA, very elaborate and covered many aspects. Olsen highlights several risk factors associated with entry in SEC according to published research in the USA. Their case studies were reconstructed as they shared personal information on entry into SEC and later the information extrapolated to see the similarities and differences and gaps that need further redress in addressing SEC. One limitation encountered with this method of data collection is where such child survivors could not express themselves or write in English. The researcher had to use local language and translate the information.

Ethical consideration

Researchers sought consent from participants before conducting interviews. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Makerere University School of Social Sciences, Kampala, Uganda and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology; Ref SS.4984.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

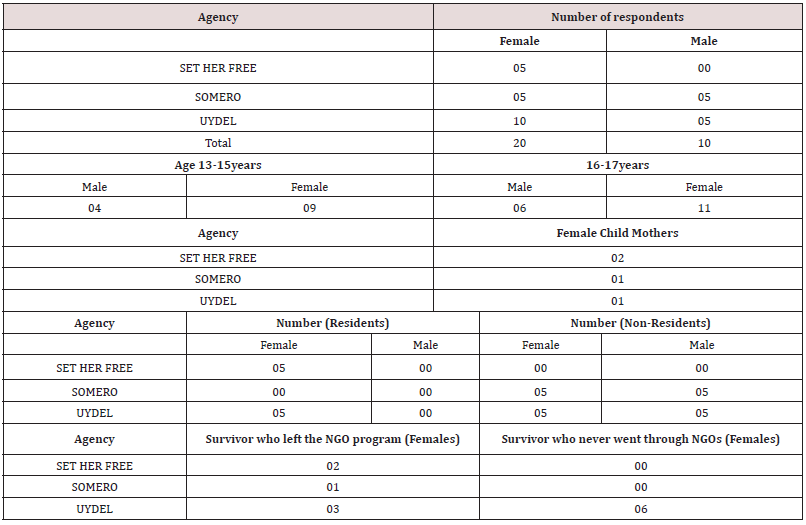

We managed to access 36 survivors for the interview. of these 30 were under rehabilitation. (20 girls and 10 boys) and 6 had left the NGO facilities and leaving on their own. Majority of respondents (17) were in the age bracket 16-17 years and another 13 fell in the age bracket 13 -15 year. Girls were predominantly more represented compared to boys. All these 30 respondents participated in the Tool Venn and River of Life. Four of these had children. 10 participants were resident at the NGO facility the rest 0of the 20 were commuting from their resident places. The remaining six (6) were past survivors (adults) who had gone through the NGO rehabilitation programs. All respondents acknowledged past involvement in SEC involving multiple partners and use of alcohol. Boys acknowledge the use of drugs. One site (Set Her Free had no male respondents) (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1: Number of Respondents per study site (Tool Venn and River of Life 30 respondents and 6 for the Focus group discussion).

Table 2: The other staff and other participants. NGO staff and other participants and other informants.

Hardships and traumatic experiences of child sexual exploitation survivors

We noted from the discussions that all survivors had been recruited and moved to the places of exploitation. Many noted that they faced early sexual involvement and defilement. More worrying was sexual abuse inflicted by people known to the children such as step parents, relatives, teachers and peers referred to as boyfriends who had also engaged in early elevated sexual experiences [15]. One female survivor mentioned, “In my school, the teachers always suggest sexual relationships to female students and one is harassed if she refuses. I was forced to change school but faced the same challenge where I went”. The extreme poverty that children experienced, dropping out of school, scarcity of food, clothing and share a single room with their parents aggravated the misery at homes in the slums, forcing many survivors to flee to the streets for survival observed on NGO staff. Sometimes survivors were forced to stay out late at night before being allowed in to sleep, exposing them to unbearable life at homes. The study noted that child survivors faced varied traumatic incidences varying from physical, emotional and sexual abuse including being hit with objects daily verbal abuse, kicks, burns, and other less severe cases like food denial, accusation of crimes among others. The findings indicated that most of the sex exchange (direct prostitution) happened in brothels, lodges and bars. We did not hear prostitution happening on the streets. Some children noted that there was indirect sexual exploitation in bars during karaoke dancing shows where exploiters wanted them to dance naked. This took place more in bars during karaoke dancing/music shows where karaoke group owners encouraged girls in middle of the night to dance naked before the patrons. Survivors at a negotiated fee with the karaoke group of children dancers were also and free to go and exchange sex for money for those who showed interest in them. Few mentioned to have engaged in pornography at their residential homes involving exchange of naked photos.

NGO Good Practices in Resilience Building for Survivors of CSE

In terms of building resilience amongst the NGOs to help survivors develop abilities to accept, adapt and overcome those hardships. We investigated through the usual NGO activities of rescue, rehabilitation and reintegration into the community to get the participants responses. We were interested in those activities that were delivered and accessed to SEC survivors to be able to bounce back and adapt; frequency, innovations and complementary ones that were easy to do in resilience, sustainable and could easily be replicated given our context in a low resource setting. The study team identified two distinct areas of resilience building and complementary ones for SEC survivors existing prostitution at the three NGOS visited.

Psychological and social resilience interventions.

The findings revealed that the most prominent resilience was Psycho-social focusing on the mind- set change. These are enumerated below:

a) Building Positive Attitude during the field discussion with the survivors, there were instances which showed that some children still lamented, considered themselves as failures and not happy. The child survivors’ psychological energy was low with worries, depression and lacked positive energy. One good practice noted in the activities amongst NGO services was to help such survivors think positively, be hopeful, courageous, seek support from other peers and staff. Masten [16] observed, “Resilience building needs to focus on social and healthy functioning, focusing on strength and positive development, rather than on pathological problems or deficit model”. Child survivors observed that they were helped to be more focused, forgetting the past, working hard, having empathy, listening to inner self and having a positive mindset. Another survivor noted, “Motivational speakers come to talk to us during career guidance days. We are encouraged as we go through a session about our lives as children and youth every Wednesday”.

b) Building capacity of identifying risks and utilizing protective factors NGO practices also involved holding individual and group counselling, educative talk sessions with individual survivors as well as the groups, to identify both risks and protective factors linked to family background and the communities she plans to join after rehabilitation. An NGO manager hinted, “Here at our centre, we organize talking sessions during first weeks of entry on the risky use of alcohol and other drugs, having multiple sex partners, survival crime and the negative consequences of such behaviour tailored to the individual child and other community challenges when she leaves.” The group discussions are held more frequently to help survivors learn how to identify and address such individual risks and hardships linked to their homes, work places, community and strategies to reduce and deal with them. Survivors are given knowledge and skills about how to improve protective factors to increase individual, social and health outcomes like sexual reproductive health, hinged on high expectation, individual participation and tapping into community services in the area. These activities are usually integrated in various sessions at the centres. There were bonding sessions targeting staff on how to engage both children, and parents’ relations.

c) In addition, NGOs helped survivors to cope positively and enabled survivors to circumvent past misfortune, stress and trauma through group discussions and individual counselling sessions to tolerate and lessen stressful events of their past such as early family separation, violence, lack of basic items in homes that were experienced. Other psychological wellbeing activities that were being promoted included allowing survivors more sleeping time and rest to recover well. Discouraged use of alcohol and drugs as a quick means of coping. Staff also engaged survivors in talks and role plays to promote self-care and limit impulsive behaviour and ways of overcoming alcohol and drug addiction and the need for prayers. Findings revealed that additionally, NGO centres promoted self-protection against abuse and violence using music, drama and sports for survivors to be aware of what to do if such situations arose. Staff and children reported that some few survivors had relapsed and resorted to alcohol, drugs and prostitution to meet urgent basic needs.

d) Cognitive flexibility and emotional control in the interviews, survivors revealed that some children who left homes managed to live on their own in the slums in rented small cheap rooms. These survivors had many quick negative thoughts like going back into transactional sex, use of alcohol, drugs and stealing. It was not easy especially for girl survivor as elaborated, “The negative effects of traumatic experiences lead survivors into anger and aggression, fighting, quarrelling and apprehension about wellbeing including loss of constructive planning and a few still resorts/ relapse to prostitution.” One NGO staff noted, “Some survivors excluded themselves from others and fighting each other. Some survivors are always rude.” Survivors through a series of activities are taught how to control strong emotions of anger, fearfulness and love hence cope positively. Many activities are integrated sports, music to help address issues of coping with stress, emotions and self-awareness. Survivors are also connected to former alumni to relate and bond, share and spend time with their past peers and friends.

e) Moral compass and ethical conduct Ethical reflection and conduct are critical in helping child survivors adjust positively. One NGO staff commented, “Moral campus related activities cement survivors’ credibility, integrity and respect and here it is church or faith delivered”. It was noted during discussion, survivors were taught how to respect other people’s property, ethical conduct, not to abuse people, how to use your power and self-control, not to exploit others, know your boundaries and self-confidence. Religious activities were done through prayers, church songs with emphasis on adherence to moral and cultural norms. NGO staff confessed that they were engaged in social behaviour discussion (BCC) activities (motivation talks) use locally known ethical and positive thinking words such a “Obutemakula, obuntu bulamu, obumalirivu (respect, and determined)”.

f) Physical activity was identified as one activity that helps general health and wellbeing of young people [17]. This is an area which does not feature as a deliberate activity in social work practice despite its immense benefits which aid and strengthen the recovery process of such survivors. During field data collection, it was discovered that all the NGO staff were engaged in some form of physical activity. The common physical activities done were aerobics, netball, running, football and general exercises performed at the centres and community recreation facilities. This was done to improve socialization, promote teamwork, mental work and physical health of the survivors. The physical work activity varied in frequency, time, number of attendees and place of performance. Some NGOs had limited space and did aerobics more frequently. All survivors got involved except those with disabilities or are sick at the time. These activities were neither frequent, intensive nor vigorous except football for the boys. Girls liked exercises related to music. Girls talked to at one NGO facility mentioned, “After the exercise, we feel better and refreshed, have more energy and the stress disappears. I make friends and feel fit; express myself belter, remember what they teach us and we mix freely with all children.”. WHO [17] noted that sports and other physical activities come along with a lot psychological benefit to young people.

The second major resilience domain activity note was built around Economic empowerment of survivors

a) Social Economic Strengthening and Livelihood focused coping (SESL). The findings at NGO showed that resilient mind set building and capacity to cope was also enhanced through livelihood activities with an element of economic strengthening and enterprise development. All the three NGOs carried out SESL activities for survivors to acquire marketable vocational skills, simple business skills like financial literacy, business record keeping, business decisions, client handling and saving opportunities. One staff mentioned, “We focused on vocational training for survivors to become employable, get money, be occupied rather than lamenting about their past. Think positively about their future, upon graduation, survivors are given start up tools, materials and cash transfer to help them start businesses and settle down”.

The interviews established that survivors were linked to artisanal workshops for internship placements or to access job opportunities and the hassles in the employment industry. Some NGOs employed integrated behavioural and psychosocial approaches to help survivors build inner self and capital resources for future utilization. Other elements that were incorporated in economic empowerment for survivors included Street smart material for behaviour change, Street business tool kits that encompassed financial literacy and managing small businesses and other Income Generating Activities (IGAs), Voluntary Savings and Loan Association (VSLA), line live up physical sports mentoring programme that promoted life skills and other pro-social behaviour. The western model has not adopted SESL because most of them focus more on psychological recovery, have a welfare state system and access to education is guaranteed which help many vulnerable people to cope and adjust positive as they exist prostitution.

b) Leveraging Social Capital for SEC survivors in resilience building. The construct of Social Capital (SC) was found to be very critical in helping child survivors adjust and cope positively to start a new life. We were informed during the interviews that the survivor’s ability to recover from negative experience usually took time and was unique to every individual survivor. Coleman (1990) observed that social capital included direct and indirect resources that are by products of social networks and social support systems amongst family, friends and community members. Yet to Putnam [18] Social capital was summarized to majorly have three broad areas including bonding, bridging and networking. The interviews with survivors, shed light on survivors’ challenges when developing bonds with family members as in some instances some survivors had been forced out of parental homes. Indeed, some of the relatives facilitated their movements away from home and ended up being sexually exploited.

One NGO social worker mentioned, “We always undertake family tracing and home visits to help children increase their relationship with them; we hold parents’ meetings to discuss bonding issues with children to discuss aftercare and resettlements. However, even when invited, some parents don’t turn up”. It is challenging that some children especially young adults do not want parents to know their past; others preferred to bond with relatives. The major activities which promoted this were largely life skills which promoted individual and social abilities of understanding oneself, decision making, relating and communicating with others and making important life decisions affecting their lives.

c) External resources, bridging and networking. Engaging actors outside the organization as referral points and resources was noted as one of the practices. All these increase access and connections to community resources and referrals. Survivors go through continuous orientation on how long they should stay there to limit dependency.

Complementary resilience building activities.

The findings revealed other complementary activities key in resilience building and survivors belonged to social community systems which can be very supportive in them adjustment.

a) Child survivor involvement and Alumni contribution to recovery and positive adaption. Child survivors who exit the facility and successfully reintegrated into the community formed a supportive relationship to those survivors, still undergoing rehabilitation at the NGO facilities. Former survivors paid visits to the centres with support items like clothes, soap, sugar and sports items for the survivors. They were able to provide practical support to their friends such as linking them to employers and getting them jobs. Others directed them to institutions for internship placements. One staff noted, “Some alumni go ahead to employ our colleagues in their businesses like electronics workshops, salons and motorbike mechanics garages and this helped us to adjust and start normal life”. The alumni help a lot in behavioural change through sharing their stories, instilling hope in the survivors.

b) Parental and community participation in resilience building and survivor adaptation. Parental involvement in recovery are crucial at the NGO centre facilities and after leaving the centre. Parents are central gate keepers as they enhance recovery from trauma and strengthen bonding and part of socio-ecological viewpoints of Bronfenbrenner [19]. The staff at NGOs indicated that serious parents attend meetings with the purpose of discussing matters concerning their children’s recovery and how be of help while adjusting in normal life after the NGO facility. One female parent noted, “I always visit and encourage her, give guidance and counselling”. Some members of the community such as local leaders and business men in the catering world help in finding jobs for the survivors and places where they can work. Survivors are encouraged to tap into these resources related to their vocational skills training in areas wherever they will go to leave.

We noted that there are negative perceptions and stigmatization of survivors under rehabilitation by the community members who keep referring to them as former prostitutes. This always counterproductive and works as a barrier and slows down to the survivor’s adjustment. Some survivors did not want parents to know their previous experiences and preferred to bond with relatives. So, there is always space to bond with a close relative or other people in the community. A few survivors wanted to begin to live independently and the six who left the facility were leavening alone far away from the parents. Survivors’ experience in bouncing back to normal lives is different and few mentioned parents as pivotal in their recovery. The hardships survivors faced varied in terms of age, location and perpetuators.

Discussion

study had two overarching objectives; one was to understand the hardships and trauma experienced by the survivors of SEC. The second was to describe NGO good practices and interventions used to address these adversities in resilience building to help in their full recovery. Despite the limitation of the study in terms of numbers of NGOs reached, and the study participants, results showed that resilience building process amongst the NGOs is delivered in a “buffet style’ and multiple faceted; takes a while to be delivered, absorbed by the survivors. The hardships and triggers faced by survivors in homes and places of exploitation were enormous some had terrifying effects. The survivor response to resilience building vary, to some few adapt faster, while other may take longer.

Most of the survivors admitted there being an incidence of early separation from their parents either due to death or family conflicts making the survivor vulnerable to trafficking and eventual exploitation. To many survivors their families were also struggling economically, exposing the children to massive denial of basics and abuse at hands of guardian and relatives. There were cases of incest in some homes, defilement by men, teachers and boyfriends who promised economic support introducing unwanted early sexual activities. Families were dysfunctional and children developed conduct problems that triggered other anti-social problems such drug and alcohol use Indeed, as mentioned by one NGO staff, many girls on admission exhibited bouts of fear, anxiety, addiction problems, low self-esteem and low self-efficacy.

Children who face early sexual involvement and abuse as the data has showed are more likely to be candidates for SEC, drug use and other anti-social [20] and criminal activities in future use [21,22]. In the USA children who enter prostitution are largely a product of juvenile delinquency and have a history of detention and substance use [23]. The case here in Uganda is more about violence, poverty and failure of social support systems to take care of children. Substance abuse and sex exploitation comes in later during exploitation but not as a major trigger and part anti-social behaviour exhibited by the survivors in their past [24]. These major factors working at different times are strengthened by early onset of hardships in homes, abuse, early sexual involvement and peer influence are key risk factors that escalate SEC.

Two distinct areas in resilience building were identified, Psycho-social and Economic empowerment. NGOs Staff adopted an integrated resilience building activity geared towards recovery from the past trauma. It was difficult to place the resilience activities on linear scale and determine which activity comes first. It covered activities in areas of positive outlook, coping with oneself and cognitive flexibility. Other activities aimed at identifying risks and protective factors, knowledge, skills, physical, moral campus and cognitive flexibility. Hurd and Zimmerman (2010) called these compensatory, protective and challenging models of resilience building to empower, buffer and inoculate survivors from future misfortunes and negative outcomes associated with SEC in order to bounce back positively in life.

Another good practice in resilience building was in the area of economic empowerment, a core activity in NGOs added to psychosocial commo in western world. Social economic strengthening and livelihood coping (SESL) involved vocational skills training meant to yield positive survive, bonding and networking. Studies done in the past demonstrated that vocational and another livelihood training combined with HIV/AIDS education lowered risky sexual behaviour [8,25]. NGO staff believed that this helped survivors to acquire money which was important to deal with any economic needs and challenges in future. This activity helped survivors to access employment, be able to earn a living and live independently. SESL addresses economic challenges of unemployment and lack of money which are probable cause for entry in prostitution, hence able to meet basic needs. These activities work as a means to disrupt negative behaviours and risk factors related to survival crime, homelessness and sex work. Southwick [11] called this self-inoculation where the survivors developed an adaptive stress response and became more resilient than normal to the negative effects of future stressors. One staff observed that survivors healed faster if they spent less time in SEC while others take longer depending on time spent at the facilities”. In the field discussions with children and staff, we noted the big variation in adjusting and survivors faced varying physical and psycho- social problems including the urge to control sexual distress.

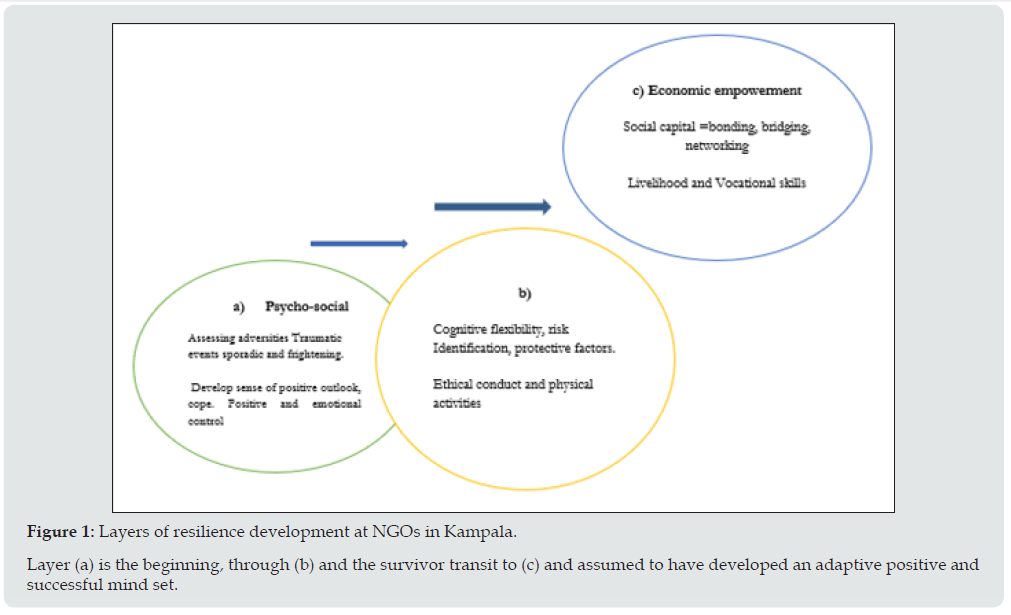

The study showed that resilience building activities at NGOs in Kampala are integrated and delivered more in a buffet approach by NGO staffs as a wide menu of activities, each activity may solve one of the hardships and also deal with negative emotions like anger unknowingly as survivors experienced different hardships emotional social and economic. These to a great extent need individual approach in a context of multiple interventions involving, parents and communities. We noted that survivors can adapt, transform and be successful in absence of the parental factors, if many resilient activities are undertaken and other key players like peers and communities also participate and help in their adjustment. In some cases, as many did not want to go back to villages far away from the city and NGO Staff had to accept this option. We recorded survivors who had successfully bounced back successfully in their business enterprises and largely benefited from the life skills sessions, bonding and networking-social capital with colleagues and providing peer support. Survivors may have developed on their own additional life skills and capacity that enabled them to cope in addition to what NGO staff contributed, giving credence to Saleeby [26] Strength Perspective theory that clients who approach service agency have some minimal skills developed on their own to build on (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Layers of resilience development at NGOs in Kampala. Layer (a) is the beginning, through (b) and the survivor transit to (c) and assumed to have developed an adaptive positive and successful mind set.

Moral compass as psycho-social resilient intervention was used as a good tool to buffer the survivors from past negative thoughts as they sought spiritual support and encouraged forgiveness of those who offended them in the past. In many instances, spirituality was linked to positive coping and seeking support from higher powers. There was a lot of variations in the way moral campus is promoted at the three NGOs largely influenced by the religious background of the directors of NGOs. Activities that build resilience among survivors around coping included life skills promotion, emotional healing though prayers and engagement in sports and music.

Studies by Luther (2000) and Ungar (2012) encourage adoption of a cross-cultural and social-ecological perspective a more western approach but less on economic empowerment. The findings however, discovered the western approaches which emphasise psycho-social in a welfare state situation alone, are not sufficient alone to make a survivor bounce back into positive life. Survivors needs and hardship were so varied, resources to intervene were few and most families dysfunctional. Some survivors resent parent and relative’s involvement in their recovery from child prostitution and exploitation because of past abuse and exploitation. Uganda does not have a welfare assistance programmes common in western world that can absorb such children for a better life. A few families cannot fully bear the burden of re-admission of rehabilitated survivors due to high levels of abject poverty.

The NGOs good practices indicated that the survivor’s exit from SEC and social integration takes time and needs more than one NGO stakeholder. Involvement and referral to other NGOs was noted a necessary ingredient in the recovery of the survivors. Referral amongst the NGOs was limited to some extent as there wasn’t a strong case management system amongst them. Dropouts and relapse of some survivors to alcohol, drugs and prostitution was reported to have re-occurred with a few cases; thus, on-going supports for survivors at the facility and when they have left is key. This must be complemented with training of social workers in a large psychosocial support area to be able to screen and identify needs such as stigma, trauma, alcohol and drug use, possibilities of relapse and re-entry in prostitution. NGOs involvement of survivors and alumni helps to give additional support in the recovery and exit from prostitution SEC.

NGOs were not following a similar pattern in delivery of resilience and variations were noted in staff capacity to deliver and access to resources which provide a good environment to promote resilience and even guidelines and frameworks to do so were not available. Survivors commuting from their homes were likely to contaminate those in the NGO boarding facility and thus delay the adaptation and adjustment time.

Conclusion

Despite the small numbers of survivors covered from NGOs visited, helping survivors to overcome risk factors and adjust to new life is a very demanding task and needs many actors at NGO and outside the facility. NGOs were handling children who had faced many risk factors, hardships and very traumatising experiences. We were able to take note of several good practices amongst the three NGOs. Multi-component interventions to address the multiple challenges experienced by survivors. Activities delivered in integrated approach with regular follow ups and tracking progress of young people in all aspects was helpful. We noticed a breadth of psycho-social and economic empowerment interventions. These were also well complemented and involved survivors, parents and tapping community resources. Findings have showed that resilience building activities don’t need to be narrowly fixed but can be broad; must be regularly done as stints of trauma can come and re-attack the survivor hence social workers and children themselves need to regularly track progress.

Both structural and behavioural interventions are needed for high-risk populations and a variety of interventions are desirable. There is need to use resiliency delivery frameworks that goes beyond the psycho-social measurements that are common in the western world, to include social capital aspects, physical activity and economic empowerment. NGO staff require capacity building, involvement of children, parents and other stakeholders. These findings provide partial prevention and intervention answers to practitioners and suggest that early child abuse, violence, family instabilities, individual, peer factors and early sexual involvement are strong triggers that create and risk environment for recruitment of children into SEC and need to be urgently addressed. The findings corroborate prior research in the west and low-income countries like Uganda that hardships faced by children in homes, early sexual activities, alcohol and drug use amongst peers are problematic issues that need early interventions, as they also open door for tolerance and may escalate SEC amongst children. The NGOs resilience building interventions need to be multifaceted- spanning over psychological, social and economic support and need to be frequently done. Interventions need to involve current, past alumni and parents and other actors because needs presented are diverse.

Limitation of the study

Much as we were able to access the survivors, we did not get a chance to review the social worker files and see what support is provided given the SEC background. Future research many need to examine such files to generate more information about their history and motive for change.

References

- Skodol AE, Bender DS, Pagano ME, Shea MT, Yen S, et al. (2007) Positive childhood experiences: resilience and recovery from personality disorder in early adulthood. J Clin Psychiatry 68(7): 1102–1108.

- Franchino Olsen H (2019) Vulnerabilities relevant for commercial sexual exploitation of children/domestic minor sex trafficking: A systematic review of risk factors. Trauma Violence Abuse 22(1): 99-111.

- Convention on Children Rights (1989) Specifically, CRC article 1, 11, 21, 32, 33, 34, 35 and 36.

- UYDEL report on (2011) Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children.

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 55/25 of 15 November 2000.

- UYDEL (2019) Uganda ECO Report.

- Sonal Pandey (2018) Trafficking of Children for Sex Work in India: Prevalence, History, and Vulnerability Analysis Explorations, ISS e-journal, Published by: Indian Sociological. Society 2 (1): 21-43.

- Rotheram Borus MJ, Weiss R, Alber S, Lester P (2005) Adolescent adjustment before and after HIV-related parental death. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 73(2): 221-228.

- Lambert MC, Rowan GT, Kim S, Rowan SA, Ann JS, et al. (2005) Assessment of behavioural and emotional strengths in Black children: Development of the Behavioral Assessment for Children of African Heritage. Journal of Black Psychology 31(4): 321-351.

- Monica H Swahn, Rachel Culbreth, Laura F Salazar, Rogers Kasirye, Janet Seeley (2016) Prevalence of HIV and Associated Risks of Sex Work among Youth in the Slums of Kampala. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, AIDS Research and Treatment (8).

- Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R (2014) Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 5(25338).

- Preble KM (2015) Creating trust among the distrustful: A phenomenological examination of supportive services for former sex workers. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment and Trauma 24(4): 433-453.

- Cimino AN (2013) Developing and testing a theory of intentions to exit street-level prostitution: A mixed methods study. Arizona State University, ProQuest.

- Kingston Rajiah, Coumaravelou Saravanan (2014) The Effectiveness of Psychoeducation and Systematic Desensitization to Reduce Test Anxiety among First-year Pharmacy Students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical education 78(9): 163

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K (2006) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 45: 192-202.

- Ann S Masten (2011) Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology 23(2): 493–506.

- World Health Organization (2010) Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

- Putnam RD (2000) Bowling Alone: American declining social capital. Culture and politics: 223-234.

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Boles S, Biglan A, Smolkowski K (2006) Relationships among negative and positive behaviours in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 29: 33–52.

- Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand R, Miller KS (2001) Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review 21(4): 493-519.

- Martin A, Ruchkin V, Caminis A, Vermeiren R, Henrich CC, et al. (2005) Early to bed: A study of adaptation among sexually active urban adolescent girls younger than age sixteen. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44(4): 358-367.

- Hannabeth Franchino-Olsen (2021) Frameworks and Theories Relevant for Organizing Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children/Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking Risk Factors: A Systematic Review of Proposed Frameworks to Conceptualize Vulnerabilities. Trauma Violence Abuse 22(2): 306-317.

- Lanctot N, Smith CA (2001) Sexual activity, pregnancy, and deviance in a representative urban sample of African American girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 30(3): 349-372.

- Janestic Mwende Twikirize, Paul Fredrick Mugume, Julius Batemba (2019) Young empowered and dignified: reversing the culture of sex work among Uganda’s urban youth through vocational skills training. African journal of social work. 9: 2.

- Saleebey D (1997) The strengths perspective in social work practice. New York Longman.

- ECPAT France (2014) Review of good practices regarding reintegration of girls and women 16-14 years in situation of sexual exploitation in eastern Africa region.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...