Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Psychiatric and Medical Comorbiditiesinpatients With Bipolar Disorder: A Hospital Based Study Volume 2 - Issue 3

Ajaz Ahmad Suhaff*, A w khan, Sajid Mohammad wani, Bilal Ahmad and Yasmeen Jan

- Department of Psychiatry, India

Received: April 17, 2019; Published: April 26, 2019

Corresponding author:Ajaz Ahmad suhaff, Department of Psychiatry, India

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2019.02.000136

Abstract

The two most common bipolar disorders are bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder. Comorbid psychiatric disorders usually precede the onset of bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder often coexists with other Axis I and Axis II disorders. Studies have shown that patients with mood disorders have more comorbid medical illnesses. Research has suggested that that there may be underlying biological mechanisms linking mood disorder and many medical illnesses.The current study will determine the psychiatric and medical disorders in a sample of patients with bipolar affective disorder in a general hospital setting.

Aims and Objectivest: study the socio-demographic profile of patients with Bipolar affective disorder, to study the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in patients with Bipolar affective disorder and to study the prevalence of medical comorbidities in patients with Bipolar affective disorder.

Methodology: This cross-sectional study was conducted at the department of Psychiatry, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), Medical College and hospital, Bemina, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir. Psychiatry department at SKIMS-MC is a General Hospital Psychiatry unit.

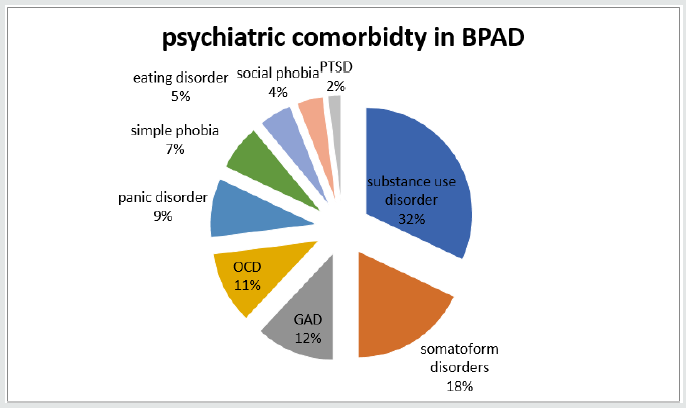

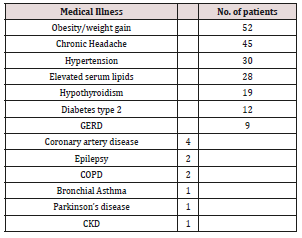

Results: In the present study the mean age of patients was 34.3 years, Majority of patients were females, married. In this study, obesity/ weight gain (n=52), chronic headache (n=45), hypertension (n=30), elevated serum lipids (n=28), thyroid disorders (n=19), diabetes (n=12), GERD (n=9), CAD (n=4), epilepsy (n=2), COPD (n=2), bronchial Asthma (n=1), Parkinson’s disease (n=1), CKD (n=1) were among the medical comorbidities. In this study the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in patients with BPAD were Substance use disorder (n=32), somatoform disorders (n=18), Generalized anxiety disorder (n=12), obsessive and compulsive disorder (n=11), panic disorder (n=9), simple phobia (n=7), eating disorders (n=5), social phobia (n=4), and PTSD (n=2).

Conclusion: The current study suggested that patient suffering from bipolar affective disorder are at increased risk of developing medical or psychiatric comorbidities. It is very important for the treating physician to be aware of the prevalent medical and psychiatric conditions patients with bipolar affective disorders and knowledge of these comorbidities help in prevention, early detection and treatment of such illnesses as well will improve treatment response and prognosis in bipolar patients itself. Awareness among healthcare professionals about the risks to which patients withaffective disorders are exposed is of great importance, as the medical illnessesare likely to coexist with a mood disorder, which may help to improvediagnostics and management and therefore clinical and social care for patients. Overall, the presence of comorbidities in BPD has negative prognostic implications for psychological health and for medical well-being and longevity. In order to improve quality of life, prognosis and life expectancy for those with these illnesses, it is important that further researches on this topic should be continued.

Keywords: Bipolar Disorder; Psychiatric Comorbidity; Medical Comorbidity; Anxiety Disorders; Substance Abuse

Background

A complex, chronic mood disorder involving repeated episodes of depression and mania/hypomania is referred as Bipolar disorder [1]. The two most common bipolar disorders are bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder. The lifetime prevalence of MDD Is around 12.2% to 16.2% [2,3] while as the prevalence of bipolar disorder are significantly lower, ranging from 0.9% to 4.4% [4,5]. In Bipolar disorder I prevalence has been found to range from 0.8% to 3.3% [6,7] while as in Bipolar disorder II prevalence has been estimated at around 0.5% to 1.1% [8] The presence of more than one disorder in a person, for a defined period of time is referred as Comorbidity[9] Comorbidity can be of three main types:[10]

1. Comorbidity of physical and psychiatric disorders, e.g. depression and hyperthyroidism;

2. Comorbidity of related disorders, e.g. anxiety and depression; and

3. Comorbidityof disorders indirectly related, e.g. psychotic depression and substance abuse.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders usually precede the onset of bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder often coexists with other Axis I and Axis II disordersand studies have found that psychiatric comorbidity in bipolar disorder range from 50% to 70% [11], In a Study with bipolar disorder, 65% patients met DSM-IV criteria for at least 1 comorbid lifetime Axis I disorder, whereas 42% had 2 or more Axis I comorbidities, and 24% had 3 or more [12]. Bipolar patients with psychiatric comorbidity had more mixed features, depressive episodes, and suicide attempts; poorer outcome and treatment compliance [10]. In another study, substance use disorders also follow the onset of bipolar disorder [13]. Sixty percent of premature deaths in those with serious mental illness are as a result of general medical conditions [14]. Studies have shown that patients with mood disorders have more comorbid medical illnesses. Researchhas suggested that that there may be underlying biological mechanisms linking mood disorder and many medical illnesses [15-18].

The current study will determine the psychiatric and medical disorders in a sample of patients with bipolar affective disorder in a general hospital setting.

Aims and Objectives

a) To study the socio-demographic profile of patients with Bipolar affective disorder.

b) To study the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in patients with Bipolar affective disorder.

c) To study the prevalence of medical comorbidities in patients with Bipolar affective disorder.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectionalstudy was conducted at the department of Psychiatry, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences(SKIMS),Medical College and hospital, Bemina, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir. Psychiatry department at SKIMS-MC is a General Hospital Psychiatry unit. The study was approved by institutional ethical committee.

The patients attending the hospital outpatient department giving a voluntary consent were included in the study. The present study was conducted on patients with bipolar affective disorder. The sample comprised 100 patients attending psychiatry OPD diagnosed as Bipolar Affective Disorder using ICD 10 during the period of june 2017 to june 2018 [19]. The diagnosis for the study group was confirmed by M.I.N.I (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) [20]. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used in the study.

Inclusion Criteria for patient:

a) Patients should fulfill ICD -10 criteria for Bipolar affective disorder.

b) Age of the patient should be 18 years or above.

c) Illness duration of at least 12 months.

d) Patients who are able to provide informed consent.

Exclusion Criteria for patient:

a) Patients aging below 18 years of age.

b) Patients who are not willing to participate.

c) Patients who had medical or psychiatric illness before the diagnosis of BPAD.

Methodology

Instruments:

a) Demographic profile and clinical data sheet of patients. Intake data of each patient was recorded on a specially designed proforma. This consisted of details about age, sex, marital status, educational status, occupation, socioeconomic status, residence, type of family.

b) International Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (ICD-10)

[19] Based on the clinical assessment, the diagnosis was made according to ICD-10 clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines.

c) Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I) [20]

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) is a short structured diagnostic interview, developed jointly by psychiatrists and clinicians in the United States and Europe, for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders.

Results

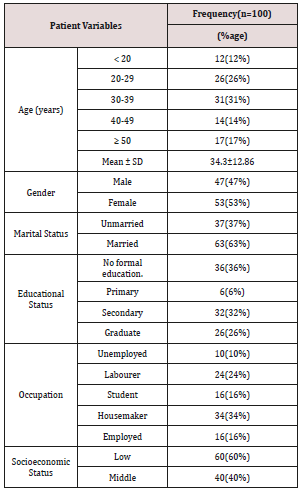

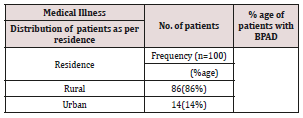

In the present study the mean age of patients was 34.3 years, Majority of patients i.e. 31% (n=31) were from 30-39 years of age group followed by 26% (n=26) of patients in the age group of 20-29 years ,17% (n=17) in ≥ 50 years,14% (n=14) in the age group of 40-49years and 12% (n=12) < 20years. Majority of BPAD patients were females i.e. 53% (n=53) and males were 47% (n= 47). Among 100 patients most of them were married 63% (n=63) and 37% (n= 37) were unmarried with no formal education i.e. 36% (n=36) , 32% (n=32%) had secondary education, 26% (n=26) were graduate and 6% (n=6) had primary education. Majority of the patient in our study belonged to low socioeconomic status i.e.60% (n= 60) and 40% (n=40) belonged to middle socioeconomic status. Most of patients i.e. 86% (n=86) had rural residence and 14% (n=14) had urban residence (Tables 1-5) and (Figure 1).

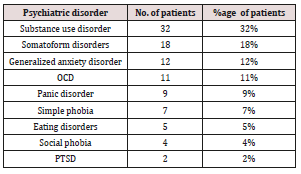

In 82% (n=82) of patients there was no family history of psychiatric illness and in 18% (n=18) of patients, mental illness in any other family member was present. In present study, 87% (n=87) of patients, no medical illness was present in family member and 13% (n=13) of patients had medical illness present in family In this study, obesity/ weight gain (n=52), chronic headache (n=45), hypertension (n=30), elevated serum lipids (n=28), thyroid disorders (n=19), diabetes (n=12), GERD (n=9), CAD (n=4), epilepsy (n=2), COPD (n=2), bronchial Asthma (n=1), Parkinson’s disease (n=1), CKD (n=1) were among the medical comorbidities. In this study the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in patients with BPAD were Substance use disorder (n=32), somatoform disorders (n=18), Generalized anxiety disorder (n=12), obsessive and compulsive disorder (n=11), panic disorder (n=9), simple phobia (n=7), eating disorders (n=5), social phobia (n=4), and PTSD (n=2).

Discussion

This study examined the Medical and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar disorder (BPD) is highly prevalent disorder by the presence of comorbid conditions and these comorbidities has negative prognostic implications for psychological and medical well-being and longevity.[16,17] Bipolar disorders are associated with psychiatric and medical comorbidities and simultaneous diagnosis and their treatment is equally important [21,22]. Most patients suffering from bipolar disorder met criteria for 3 or more lifetime psychiatric disorders. Patients with bipolar disorder has impairment even during the period of remission due to physical and psychiatric comorbidities and can lead to disability. WHO classification of disability have placed BPD seventh in the disability cause [23-26], The complex mechanisms underlying the comorbidity in Bipolar disorders may suggest that the causal relationships are likely to be bidirectional [27,28].

In our sample the medical conditions associated with bipolar disorder were Obesity/weight gain(52%), Headache (45%), Hypertension (30%), Elevated serum lipids (28%), Thyroid disorders (19%), Diabetes (12%), GERD (9%), Coronary artery disease (4%), Epilepsy and COPD 2% each, Parkinson’s disease, Bronchial Asthma, and chronic kidney disease 1 % each.

Burden of overweight has increased rapidly over the past decades globally. Obesity/Overweight are emerging as an important public health problem in India [29,30]. In India reported prevalence of overweight in range of 1.5%–24.0%in general population and showed rapid increase [31]. In our study the 53% patients showed weight gain which is higher than the prevalence in general population, Patients with Bipolar disorder tend to be overweight and reason could be the treatment of bipolar disorder especially valproate, carbamazepine, Lithium and antipsychotics which may also increase the risk of other comorbid medical disease [32-36].

Another reason for could be the comorbid eating disorder which includes the excessive carbohydrate consumption and low rates of exercise [37,38]. Headache is prevalent in every country affecting both genders and all socioeconomic levels. In general the percentages of the adult population with an active headache is 46% [41,42].

In our study 47% patients were suffering from headaches which is almost similar to the prevalence of general population. The connection between migraines and bipolar disorder is so strong that over one-third of people living with bipolar suffer from migraines [43,44]. Researchers think that there may be a genetic abnormality in serotonin, dopamine and glutamine neurotransmitters that contributes to both migraine headaches and bipolar disorder [45]. Hypertension is an important public health problem in developed and developing nations [46,47].The prevalence of hypertension in general population is 20.9% and in our study 30% patients with BPAD was suffering from hypertension which is higher than the general population [48]. The link between bipolar affective disorder and hypertension depends upon various factors such as Life styles, obesity and psychotropic medicines in particular second-generation antipsychotics are likely to play a role [49-51].

The effect of psychotropic medications and associated weight gain or the complications of treatment with some atypical antipsychotics may lead to diabetes as well as a marked increase of serum lipids [52]. A bipolar disorder and metabolic disorders, such as coronary artery disease and diabetes type 2, have strong genetic links and may share some common pathophysiological pathways [53]. The comorbidity of thyroid disorder in individuals with bipolar disorders has a well-established link. Lithium a mood stabilizer which is a common treatment for bipolar disorder can also lead to thyroid disorders as a common side-effect of the drug [54]. A higher burden of medical illness is indicative of a more severe illness course, with greater impairment in functioning which has been also seen in previously reported findings.The presence of a medical condition increases the risk of developing a mood episode/ disorder and vice versa [49]. Bipolar disorder often coexists with other Axis I disorders.In our study the psychiatric disorders associated with bipolar affective disorders were Substance use disorder (32%), somatoform disorders (18%), Generalized anxiety disorder (12%), obsessive and compulsive disorder (11%), panic disorder (9%), simple phobia (7%8), eating disorders (5%), social phobia (4%), and PTSD (2%).

Psychiatric disorders with bipolar disorder compared to their rates in the general population are higher and can pose a therapeutic challenge as well as a diagnostic dilemma [55]. A careful assessment, accurate history form bipolar patient is a challenge due to overlap between symptoms of BPAD and other psychiatric conditions.

Comorbid Substance use disorder was found to exist in 48- 61% of patients with bipolar affective disorder in some studies [56-58]. The significant indicator for the course of bipolar disorderisdrug abusewith regard to the individual and in relation to family history of drug abuse. Patients with bipolar affective disorder are at higher risk for anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder, simple phobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and panic disorder [59,60]. Substance use and anxiety disorders are higher in patients with bipolar disorder than in general population, similar results were found in our study [61,62].

Conclusion

The current study suggested that patient suffering from bipolar affective disorder are at increased risk of developing medical or psychiatric comorbidities. It is very important for the treating physician to be aware of the prevalent medical and psychiatric conditions patients with bipolar affective disorders and knowledge of these comorbidities help in prevention, early detection and treatment of such illnesses as well will improve treatment response and prognosis in bipolar patients itself.Awareness among healthcare professionals about the risks to which patients withaffective disorders are exposed is of great importance, as the medical illnessesare likely to coexist with a mood disorder, which may help to improvediagnostics and management and therefore clinical and social carefor patients. Overall, the presence of comorbidities in BPD has negative prognostic implications for psychological health and for medical well-being and longevity. In order to improve quality of life, prognosis and life expectancy for those with these illnesses, it is important that further researches on this topic should be continued.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2001) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn).

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Delmer O, Jin R, Merikangas K, et al. (2005) Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6): 593-602.

- Patten S, Wang J, Williams J, Currie S, Beck C, et al. (2006) Descriptive epidemiology of major depression in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 51(2): 84-90.

- Merikangas K, Akiskal H, Angst J, Greenberg P, Hirschfeld R, et al. (2007) Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(5): 543-552.

- Weissman M, Blandm R, Canino G, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, et al. (1996) Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 276(4): 293-299.

- Grant B, Stinson F, Hasin D, Dawson D, Chou S, et al. (2005) Prevalence, Correlates, and Comorbidity of Bipolar I Disorder and Axis I and II Disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2005(66): 1205-1215.

- Judd L, Akiskal H (2003) The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorder in the US population: renalaysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord 73(1-2): 123-131.

- Regier D, Farmer M, Locke D R B, Keith S, Judd L, et al. (1990) Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 264(19): 2511-2518.

- Wittchen HU (1996) Critical issues in the evaluation of comorbidity of psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 168: 9-16.

- Yehuda Sasson, Miriam Chopra, Eran Harrari, Keren Amitai, Joseph Zohar, et al. (2003) Bipolar comorbidity: from diagnostic dilemmas to therapeutic challenge. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 6(2): 139-144.

- Vieta E, Colom F, Corbella B, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, et al. (2001) Clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in bipolar I patients. Bipolar Disord 3(5): 253-258.

- McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Frye MA, et al. (2001) Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158(3): 420-426.

- Strakowski SM, Sax KW, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Hawkins JM, et al. (1998) Course of psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes co-occurring with bipolar disorder after a first psychiatric hospitalization. J Clin Psychiatry 59(9): 465-471.

- Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Altshuler LL, Denicoff KD, Frye MA, et al. (2001) The Stanley foundation bipolar network. 2. Preliminary summary of demographics, course of illness and response to novel treatments. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 41: 177-183.

- Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, Pincus HA, Shad M, et al.(2004) Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 6(5): 368-373.

- Carney CP, Jones LE (2006) Medical comorbidity in women and men with bipolar disorders: a population-based controlled study. Psychosom Med 68(5): 684-691.

- Ramasubbu R, Beaulieu S, Taylor V, Schaffer A, McIntyre R, et al. (2012) The CANMAT task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid medical conditions: diagnostic, assessment, and treatment principles. Ann Clin Psychiatry 24(1): 82-90.

- Kupfer D (2005) The increasing medical burden in bipolar disorder. JAMA 293(20): 2528-2530.

- Evans D, Charney D, Lewis L, Golden R, Gorman J, et al. (2005) Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. ICD 10 World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: WHO 1992. Biol Psychiatry 58: 175-189.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, et al. (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59(20): 22-33.

- Kupfer DJ (2005) The increasing medical burden in bipolar disorder. JAMA 293(20):2528-2530.

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997) Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349(9063): 1436-1442.

- McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Yatham LN (2004) Comorbidity in bipolar disorder: a framework for rational treatment selection. Hum Psychopharmacol 19(6): 369-386.

- Kessler R (1999) Comorbidity of unipolar and bipolar depression with other psychiatric disorders in a general population survey. In: Tohen M, ed. Comorbidity in Affective Disorders. New York: Marcel Dekker pp: 1-25.

- Sole B, Bonnin CM, Torrent C, Martinez-Aran A, Popovic D, et al. (2012) Neurocognitive impairment across the bipolar spectrum. CNS Neurosci. Ther 18(3): 194-200.

- M Bailara K, Demotes-Mainard J, Swendsen J, Mathieu F, Leboyer M, et al. (2009) Emotional hyper-reactivity in normothymic bipolar patients. Bipolar Disord 11(1): 63-69.

- Krishnan KR (2005) Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom. Med. 67(1): 1-8.

- Ramasubbu R, Beaulieu S, Taylor V, Schaffer A, McIntyre R, et al. (2012) The CANMAT task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid medical conditions: diagnostic, assessment, and treatment principles. Ann Clin Psychiatry 24(1): 82-89.

- Evans D, Charney D, Lewis L, Golden R, Gorman J, Krishnan K, et al. (2005) Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry 58(3): 175-189.

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384(9945): 766-781.

- Jain S, Pant B, Chopra H, Tiwari R (2010) Obesity among adolescents of affluent public schools in Meerut. Indian J Public Health 54(3): 158-160.

- Jain S, Pant B, Chopra H, Tiwari R (2010) Obesity among adolescents of affluent public schools in Meerut. Indian J Public Health 54(3): 158-160.

- Mc Elroy SL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Dhavale D, Keck PE Jr, et al. (2002) Correlates of overweight and obesity in 644 patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 63(3): 207-213.

- Fagiolini A, Frank E, Houck PR, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, et al. (2002) Prevalence of obesity and weight change during treatment in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 63(6): 528-533.

- Vendsborg PB, Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ (1976) Lithium treatment and weight gain. Acta Psychiatr Scand 53(2): 139-147.

- Gitlin MJ, Cochran SD, Jamison KR (1989) Maintenance lithium treatment: side effects and compliance. J Clin Psychiatry 50(4): 127-131.

- Swann AC (2001) Major system toxicities and side effects of anticonvulsants. J Clin Psychiatry 62: 16-21.

- Keck PE, McElroy SL (2003) Bipolar disorder, obesity, and pharmacotherapy associated weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry 64(12): 1426-1435.

- Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, et al. (2007) The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 27(3): 193-210.

- (2011) World Health Organisation and lifting the burden 2011. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2004. World Health Organisation.

- Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, et al. (2007) The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 27(3): 193-210.

- World Health Organisation and lifting the burden (2011). Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2004. World Health Organisation.

- World Health Organisation and World federation of neurological Disorders 2004 Geneva. World Health Organisation.

- Holland J, Agius M (2011) Neurobiology of bipolar disorder—lessons from migraine disorders. Psychiatria Danubina 23:S162-S165.

- Oedegaard KJ Greenwood TA, Lunde A, et al.(2010) A genome-wide linkage study of bipolar disorder and co-morbid migraine: replication of migraine linkage on chromosome 4q24, and suggestion of an overlapping susceptibility region for both disorders on chromosome 20p11. Journal of Affective Disorders 122(1-2):14-26.

- P M Kearney, M Whelton, K Reynolds, P K Whelton, J He (2004) Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. Journal of Hypertension 22(1): 11-19.

- Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, et al. (2005) Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 365(9455): 217-223.

- Saunders KEA (2010) Goodwin GM. The course of bipolar disorder. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 16(5): 318-328.

- Johannessen L, Strudsholm U, Foldager L (2006) Increased risk of hypertension in patients with bipolar disorder and patients with anxiety compared to background population and patients with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord 95(1–3): 13-17.

- Nasrallah HA (2003) Factors in antipsychotic drug selection: tolerability considerations. CNS Spectr 8(11): 23-25.

- Kemp DE, Gao K, Chan PK, Ganocy SJ, Findling RL, et al. (2010) Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: relationship between illnesses of the endocrine/metabolic system and treatment outcome. Bipolar Disord 12(4): 404-413.

- Soreca I, Fagiolini A, Frank E, Houck PR, Thompson WK, et al. (2008) Relationship of general medical burden, duration of illness and age in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Psychiatr Res 42(11): 956-961.

- Thomsen AF, Kessing LV, (2005) Increased risk of hyperthyroidism among patients hospitalized with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 7(4): 351-357.

- Zarate C, Tohen M , (2002) Bipolar disorder and comorbid axis I disorders: diagnosis and management. In: Yatham L, Kusumakar V, Kutcher S, Bipolar Disorder: A Clinician’s Guide to Biological Treatments. New York: Brunner-Routledge 67(1): 115-138.

- Salloum IM, Thase ME (2000) Impact of substance abuse on the course and treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 2(3 Pt 2): 269-280.

- Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S, Kupfer DJ (2000) Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord 2: 191-195.

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BL, Keith SJ, et al. (1990) Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA 264: 2511-2518.

- Brunette MF, Noordsy DL, Xie H, Drake RE, (2003) Benzodiazepine use and abuse among patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv 54(10): 1395-1401.

- Zarate C, Tohen M, (2002) Bipolar disorder and comorbid axis I disorders diagnosis and management. In: Yatham L, Kusumakar V, Kutcher S, eds. Bipolar Disorder: A Clinician’s Guide to Biological Treatments. New York: Brunner-Routledge pp: 115-138.

- McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck Jr PE, Frye MA, (2001) Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 158(3): 420-426.

- Brady KT, Lydiard RB, (1992). Bipolar affective disorder and substance abuse. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 12(1): 17-22.

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, et al. (1990) Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. Journal ofthe American Medical Association 264(19): 2511-2518.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...