Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Peace Education and Conflict Resolution Curricula for Middle School Students Volume 2 - Issue 3

Michael R Van Slyck1*, Linden L Nelson2, Rebecca H Foster3 and Lucille A Cardella4

- 1 Department of Psychology, Keiser University-Clearwater, USA

- 2 California Polytechnic State University, USA

- 3 Washington University, USA

- 4 University at Albany, State University of New York, USA

Received: May 16, 2019; Published: May 28, 2019

Corresponding author:Michael R Van Slyck, Keiser University-Clearwater, Department of Psychology, New York, USA

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2019.02.000138

Abstract

This paper presents a critical review of six peace education and conflict resolution curricula for the middle school level. It represents a follow-up to a previously published critical review which examined these types of curricula at the high school level. The previous review established a set of educational objectives to be met by these curricula which have been incorporated in this review. These include: knowledge and understanding, competencies, attitudes and values, and efficacy and outcome expectancies regarding the principles and practice of social conflict management and dispute resolution. In addition, such factors as grade appropriateness, interest, and difficulty were rated. These issues were examined on a middle school level using an improved methodology derived from the first effort. Twenty-two reviewers were solicited through the auspices of the American Psychological Association: Division 48 membership. Each curriculum was reviewed by 5 or 6 reviewers using a revised review instrument designed by the investigators for the purpose of this study. Results of this effort indicated variability across ratings for meeting the various educational objectives. Tables are provided to show ratings for each variable examined. The results provide potentially useful evaluative and comparative information to educators who are using, plan to make use of, or are considering these types of curricula for their school or classroom. Given the lack of evaluation research that exists with regard to such curricula, this type of information may be vital for these professionals as well as for the continued growth of this field.

Peace education and conflict resolution curricula for middle school students. In a previous effort, the authors [1] examined, reviewed and rated a number of conflict resolution and peace education curricula designed for the high school level. This endeavor received favorable response because it provided readers, and potential users, with useful information on which to base decisions concerning the choice of curricula to implement in their schools. For that reason, and in the context of a specific effort to revise and improve the review and rating instruments, the authors have repeated the original process but this time with Middle School curricula. As a result, the reader will find in this paper an overall description of each curriculum, a critical review with both strengths and weaknesses, as well a series of tables providing ratings on multiple relevant dimensions. Providing the type of information delineated above to as wide an audience as possible is the primary purpose of the paper. In that context it is not viewed as appropriate to engage in a lengthy discourse on the value and appropriate use of such curricula here. However, we will comment briefly on the broader topic of the use of conflict resolution programs in schools and where the curricular approach fits in this general endeavor

For some time, especially in the 90’s, there was a belief that there was escalating youth violence, which triggered a debate about how to address this problem [2]. Educators and mental health professionals responded by addressing specific areas of interpersonal conflict through the implementation of peace education and conflict resolution programs [3]. Conflict resolution curriculum-based programs were designed to teach students about conflict and alternatives to violence via preventative means such as social skills training, empathy training, anger management, investigating attitudes about conflict, active listening, increasing open communication, and increasing bias awareness [4-6] It has been argued that conflict resolution education programs have the potential to promote the individual behavioral change required for responsible citizenship and the systematic change necessary for a safe learning environment [7].

In addition to the curricular approach, the implementation of what have come to be called peer mediation programs also began and evolved, with some research based demonstrable positive effects. In their literature review on these programs, [8] noted that conflict resolution programs of this type seemed to be effective in teaching student’s integrative negotiation and mediation skills and in increasing the use of conflict strategies resulting in constructive outcomes and the reduction of student-student conflicts. [9] Found that youths who endorsed prosocial responses to conflict also showed positive indices of adjustment. Furthermore, an increase in adolescent self-esteem was an additional effect of conflict resolution interventions of this type [10]. Unfortunately, far less, indeed very little research has looked at the impact of the curricular approach. Despite this fact, many schools have implemented conflict resolution and peace education curriculum into the classroom [11]. While full-fledged evaluation research efforts, whether to examine one program or to compare two, are necessary if this area of activity is to advance, they are difficult and costly. Thus, the type of critical and comparative information provided in this paper represents a valuable source of knowledge for those using these curricula. We will conclude this brief discussion of conflict resolution programs in the educational system, by indicating that ultimately we support what has been labeled the comprehensive approach to peace education and conflict resolution which would include peer mediation, cooperative learning in the classroom, and training for teachers, administrators, and parents along with the utilization of a well-designed curriculum as a base – and to dot the last I with regard to being comprehensive, we advocate for curriculum at every grade from K - 12. However, those selecting peace education and conflict resolution curricula should be aware that not all curricula labeled as such represent reliable programs [7]. Curricula need to develop specific foundations and provide training and practice in particular skill areas. By reviewing the following educational objectives with the developmental needs of middle school students in mind, the goal of this endeavor is to provide a framework for choosing and evaluating peace education and conflict resolution curricula.

Educational Objectives

In a prior conflict resolution curricula review, [1] asserted that curricula should be designed to influence knowledge and understanding of peace and conflict, competencies necessary for peacemaking, peacebuilding, and peacekeeping, peaceful attitudes and values, and efficacy and outcome expectancies. Consistent with the objectives, [7,12] offered specific attitudes, understandings, and skills that were facilitative in the problem-solving strategies of conflict resolution. Additionally, [7] proposed a developmental sequence of these factors according to the grade levels of students. The middle school conflict resolution curriculum should address these developmentally appropriate attitudes, understandings, and skills. [7] first discussed various “orientation abilities” encompassing the values, beliefs, attitudes, and propensities that accompany effective conflict resolution including nonviolence, empathy, trust, tolerance, respect, and fairness. The orientation abilities of middle school students should also include such elements as the ability to diagnose conflicts appropriately, to select resolution strategies, and to take action to inform when prejudice is displayed. Perception abilities are comprised of the manners in which people perceive reality such as empathizing in order to see how others view a situation or self-evaluating to recognize personal fears or assumptions. Building middle school student perception abilities needs to include training to help students recognize that conflict can escalate into violence and to understand the prevalence and glamorization of violence in society. Moreover, middle school students should be encouraged to recognize the limitations of their own perceptions and understand that selective filters bias opinions. Emotion abilities consist of behaviors to manage anger, frustration, fear, and other emotions. Middle school students would benefit from assistance in taking responsibility for their emotions as well as accepting and validating the emotions and perceptions of others. Communication abilities include behaviors of listening and speaking that allow effective exchange of facts and feelings. Conflict resolution curricula must facilitate middle school students’ use of summarizing and clarifying in order to diffuse anger and deescalate conflict. Additionally, middle school students should be taught to rephrase their own statements using unbiased and less inflammatory language.

Creative thinking abilities involve behaviors that enable individuals to be innovative in problem identification and decisionmaking [7]. Middle school students need to be shown that underlying interests, not positions, define the problems in conflict situations. Students at the middle school level are developmentally ready to use analytical tools to define problems and understand that there are often multiple, unclear, or conflicting interests to be considered. Lastly, critical thinking abilities embody the behaviors of analyzing, hypothesizing, predicting, strategizing, comparing, contrasting, and evaluating. The anticipation of both short- and long-term consequences of proposed options for conflict resolution is an imperative ability to develop in middle school students. Students must be assisted in recognizing the efficacy of committing solely to solutions that are fair, realistic, and workable [13] listed three problem-solving methods that are important to include in conflict

A. Resolution curricula:

a. Negotiation,

b. Mediation, and

c. Consensus Decision-Making

Negotiation is a problem-solving process in which the two parties in the dispute meet directly with each other to resolve conflict without the assistance of others. Mediation is a problemsolving process in which the two parties in the dispute meet directly with each other to resolve the dispute but are assisted by a neutral third party, or mediator. Consensus decision making is a group problem solving process in which all of the parties in the dispute meet to collaboratively resolve the dispute by devising a plan of action that all parties will support. A neutral party may be involved in facilitating the process. According to [7], middle school students can be taught to use these problem-solving methods through conflict resolution training. Results of such training have shown that students can successfully learn principled negotiation with peers and adults utilizing these methods. Mediating disputes among peers was another skill instilled during the training process. With conflict resolution training, middle school students can become capable of managing consensus problem-solving sessions for classroom groups of younger students. Although instruction should emphasize general principles of conflict resolution since time allotments for instructors to teach peace and conflict curricula are limited [1] ,the use of a comprehensive approach advocated by the authors would entail the implementation of conflict resolution curricula at all grade levels allowing for a variety of topics to be covered over the course of several years. Moreover, the other components of a comprehensive program (e.g., cooperative learning, peer mediation, parent training) would build from the basic foundation provided by the curricula.

Methods

a. Curricula selection and review process

A search was conducted to identify peace education and conflict resolution curricula for middle school students via various research databases and publisher catalogs. Twelve curricula for middle school students were identified. Publishers were requested to submit a copy of their curriculum for initial review by the authors to determine inclusion in the study. Six publishers supplied a copy of seven total curricula. Of these, the primary investigator selected six that appeared to be most representative of many of the educational objectives of peace education and conflict resolution for middle school students. Publishers then agreed to submit multiple copies for review. Curricula were sent to 25 potential reviewers who were to complete 36 reviews (6 per curriculum). A total of 32 curricula reviews were completed by 22 reviewers. Each curriculum was reviewed by five or six reviewers and each reviewer evaluated one or two curricula.

b. Reviewers

The international group of reviewers volunteered from the Working Group of Division 48, the Society for the Study of Peace, Conflict, and Violence: Peace Psychology, Division of the American Psychological Association. Fourteen female reviewers and eight male reviewers completed the reviews. The majority of reviewers [1] held doctoral degrees. Fifteen of the reviewers were employed in academic settings while seven of the reviewers were employed in applied clinical settings. Those in the academic setting engaged in diverse activities in conflict resolution and peace education including teaching conflict resolution to prospective teachers, acting as consultants to local school districts, developing and evaluating conflict resolution curricula and programs, teaching psychology to high school students, directing various social service programs, training mediators, and researching conflict, aggression, and violence prevention. Those in applied clinical settings also engaged in various activities in conflict resolution and peace education such as conducting workshops on conflict resolution, authoring conflict resolution books, providing conflict resolution and peer education training, supervising mental health professionals in the schools, consulting in parent education centers, conducting family therapy, and teaching individuals how to run psycho-educational treatment groups.

c. Evaluation instrument

The curriculum evaluation instrument (see Appendix A) was revised from the instrument utilized in the study of peace education and conflict resolution curricula for high school students [1]. Feedback received from reviewers on the previous curriculum review project was incorporated into the revisions. Additionally, a review of current literature on conflict resolution curricula was conducted to guide the development of items measured. The preliminary version of the revision was sent to an expert in the field of conflict resolution for review. The investigators then made final revisions. As in the previous curriculum review study [1], there were two main purposes behind the development of the evaluation instrument. One purpose was to investigate the utilization of psychological concepts by authors of the curricula and to give authors suggestions for improving the application of psychology to curricular content and pedagogy. This was achieved utilizing a Likert scale to rate the use of various psychological concepts as well as an open-ended question to elicit opinions on enhancing the use of psychological concepts. A second purpose was to provide comparative and evaluative information about peace education and conflict resolution curricula to educators and others who may use them. Again, a Likert scale was used to evaluate the influence of the curricula on various student skills related to conflict resolution and to rate the level of appropriateness of the curricula for different grade levels. Additionally, the extent to which they fulfilled their specific educational objectives was examined. Openended questions solicited reviewer commentaries on strengths and limitations of the curricula as well as suggestions for improvement beyond those previously made to address concerns about the psychological content.

d. Data analysis

Mean scares were calculated for reviewer ratings on the use of psychological concepts, the influence of the curriculum on student skills, the percentage of the curriculum devoted to different types of conflict, and the appropriateness of the curricula for various educational objectives. Responses to open-ended questions were transcribed onto a data summary form for each question. Themes were identified within the data based on recurring ideas or language in reviewers’ responses. Particularly salient and/or frequent responses, as judged by the primary author, were synthesized into the narrative passages denoting the strengths and limitations, especially regarding psychological content of the various curricula.

Results

Each curriculum reviewed was described individually with summaries of reviewers’ comments about strengths and limitations including psychological content observations. Afterwards, the reviewers’ ratings of the curricula were identified on various relevant aspects including the degree to which each curriculum seemed likely to address psychological concepts and promote educational objectives related to the development of conflict resolution and peace building skills. Conflict Resolution in the Middle School [14].

Description

In this 384 page curriculum and teacher’s guide, four major areas of conflict resolution were covered. The first section, “Essential Tools,” consisted of lessons designed to introduce students to the core conflict resolution concepts and skills. “Working Toward WinWin” consisted of lessons that build on the core concepts and skills required to help students learn to negotiate. The third section, “Dealing with Differences,” was designed to help students understand diversity and deal with conflict that stems from diversity. Lastly, “Infusion into the Standard Curriculum,” described how to reinforce skills in the context of standard middle school academic areas. The main teaching strategies included role playing, journaling, mini-lectures, brainstorming, microlabs, and small group discussion. The curriculum was based on the “Peaceable Classroom Model” which emphasizes cooperation, communication, appreciation for diversity, the healthy expression of feelings, responsible decision-making, and conflict resolution.

a. Strengths

This curriculum was regarded as a comprehensive, wellcontemplated, attractive, and ambitious curriculum, which sets the standard for teaching conflict resolution skills. Its goals were well-stated and largely well-met. It seemed highly applicable to conflicts that are likely to be common in middle school students’ peer experience. The curriculum also took a very positive view of young adolescents and their ability to be proactive. There was serious consideration of adolescents’ need for autonomy, e.g., allowing them to set the ground rules, basing role-plays on their suggestions, and encouraging them to discuss ways of exercising power. However, there was a clear emphasis on the “right to pass,” which protects shy and vulnerable adolescents as well as the privacy of all students. Encouragement and advice on including colleagues and parents in this endeavor was a valuable part of the curriculum. Sample material to facilitate reinforcement of conflict resolution skills in social systems outside the classroom was an asset. Additionally, suggestions for adapting the curriculum for different classes and subjects were provided. The skills and exercises seemed easy to adapt. The psychological content focused on affect, which was essential in a conflict resolution program. Attention given to internal dialogue was another asset of this curriculum. Although it did not directly address weapons, sexual harassment, and abuse, it enhanced efforts to cope with these issues. Activities have been field tested and provided a framework that was meaningful and could be carried out in real life. The curriculum met high pedagogic standards including opportunities for repetition, practice, and feedback. Sensible guidelines and extensive help for teachers were supplied. The publisher offered a workshop for teacher training. An extensive bibliography was furnished. Outcome observations and assessments were provided.

b. Limitations

The styles of conflict resolution appeared direct, low context, and individualistic without recognizing that most of the world’s population prefer indirect, high context, and collectivistic perspectives. Some activities appeared to work better with a dominant culture student than with minority students. The lesson on stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination tended to be simplistic in focus. Greater emphasis was placed on changing behaviors than on understanding the reasons behind the behaviors from different viewpoints. A more thorough treatment of peer influence and peer pressure seemed warranted. In this curriculum, peer pressure seemed to be defined as capitulation. Focus on the positive influence of peers and their potential to establish and model prosocial norms and behaviors could be improved for this curriculum. Additionally, a more informed discussion of peer influence including peer group norms, modeling of behaviors, and the structuring of opportunities could be enhanced. There was an omission of some rules of conflict and the need for brainstorming. One suggestion for improvement was to explain rules in more detail including separating people from the problem, focusing on interests, inventing win-win options, and using objective criteria. More examples would be helpful in this regard such as narratives of conflict at the middle school level. Emphasizing that unresolved conflicts create problems would also be beneficial. This curriculum also did not address civil or international conflict. The issue of violence was handled indirectly through the discussion of violence, e.g., “Conflict Webs” Creating Peace, Building Community [15].

Description

This series of two texts designed for sixth and seventh graders included both the teacher guides and student worksheets. The sixth-grade text was 89 pages long, and the seventh-grade text was 105 pages long.

a. The sixth grade teacher’s guide was organized according to six main concepts:

a. Building community

b. The rules for fighting fair

c. Pro-social skills

d. Conflict

e. Character development

f. Understanding culture

b. The seventh grade teacher’s guide was organized according to five main concepts:

a. Building community

b. Prosocial skills

c. Anger management

d. Conflict

e. Social responsibility

Principal instructional strategies were activities, guided discussion, and journaling. Extending activities included suggestions for infusion into the daily lives of students. The goal was for students to become effective peacemakers.

c. Strengths

This curriculum contained a rich resource of carefully designed activities, which seemed appealing and stimulating for middle school students. These innovative activities were well-focused on managing conflict as a normal and resolvable feature of life and included the use of negotiation skills, mediation skills, and anger management in interpersonal settings. Conflict resolution skills were not only discussed but many opportunities were provided for practice. The examples, illustrations, and vocabulary utilized seemed accessible to middle school students. Obvious attention had been given to issues of adolescent development such as popularity, identity, and peer pressure. The use of diversity in examples aided the students in understanding diversity and consensus. The clear presentation of activities seemed to facilitate replication. The utilization of the classroom village concept within wider communities of school, neighborhood, society, and beyond were useful to introduce ideas about groups and identities. This concept provided many opportunities for the students to learn about and develop peacemaking and conflict resolution skills within emotionally safe communities. Direct involvement in a community initiative was a superb idea.

d. Limitations

One concern was what appeared to be an underlying presumption that young people were not peacemakers nor do they possess peacemaking skills. This limited the perspective of the curriculum enormously and did not acknowledge the abilities and skills which middle school students have developed. Reviewers suggested more emphasis on what students have developed in terms of conflict resolution and peacemaking skills. The curriculum focused on interpersonal conflict to the exclusion of intergroup or international conflict. Political issues were addressed to a limited degree. The influence of race and class were essential to address in order to understand factors that may contribute to conflict and violence. For instance, different perspectives concerning racism (e.g., as part of an individual’s profile, as an outcome of not knowing others, from the perspective of different groups in society, or as part of the structures and values of society) could be discussed so that different aspects and causes for conflicts based on racism could be highlighted. Also, the processes of socialization with regard to gender needed to be addressed to a larger extent. Developing awareness that adults react differently toward girls’ or boys’ aggressive behaviors was important for a better understanding of conflicts and conflict resolution. The curriculum was overly positive in indicating the effectiveness of some interventions. For instance, it underestimated the complexity of empathy and its relationship with prosocial behavior and aggression reduction. There appeared to be superficial treatment of many issues with a preponderance of ready made formulas. This type of treatment overlooked potential difficulties, which may leave students unequipped to deal with major setbacks. Additionally absent in this curriculum were accommodations for students who may be shy, isolated, or experiencing peer rejection. There were few activities designed for students who may not be as verbal as their classmates. More alternative activities such as art therapy would address this issue.

Creating the Peaceable School

a. Description

The 361 page program guide presented a theoretical overview of conflict resolution principles and instructions for assisting students in mastering the skills and knowledge to successfully apply these principles.

b. The accompanying 132-page student manual included activities divided into six sections:

a. Building a Peaceable Climate

b. Understanding Conflict

c. Understanding Peace and Peace

d. Mediation

e. Negotiation

f. Group problem solving

The primary teaching strategies were experiential learning activities, learning centers, class meetings, cooperative learning, and simulations. The focus was the creation of a cooperative school context [13].

c. Strengths

This thorough curriculum did a consistent job of teaching the value of peacemaking through an experiential and personal framework. Founded in educational and human needs theories, it provided a commonsensical approach to encouraging constructive behavior. It included a comprehensive review of standard and conventional theory about conflict resolution. The engaging material would likely elicit interest in middle school students. The primary strength seemed to be acceptance of conflict and methods of reaching constructive resolution. The curriculum emphasized choices and personal responsibility for behavior. It taught about responses based on mutual respect, discovering shared and compatible principles, and strong ethical values. Moreover, the curriculum created a schoolwide context for building peaceable relationships.

d. Limitations

The curriculum did not appear to be generalizable to a diverse school audience who come from distinct cultural frames of reference that are non-Western. The materials favored individualistic, low context, internal locus of control, dominant culture norms. Students could complete these materials yet not be prepared to manage conflicts between themselves and cultures who do not accept dominant culture assumptions. Additionally, students would not gain an understanding of conflict on an intergroup or international level. The curriculum could be improved with more attention to cross-cultural communication, issues of ethnicity, race, and class in power situations and conflicts, and the international arena. The curriculum would benefit from further development in particular areas. The role of attitudes, beliefs, and emotions in achieving meaningful communication was one area deserving expansion. In addition, there should be a more explicit distinction between positions and interests. The rules of conflict required more explanation and examples. Supplementary illustrations of brainstorming would also be beneficial. Integration of a section regarding infusing conflict resolution concepts into mainstream teaching topics was another recommendation. Attention to counseling as an appropriate response along with mediation and negotiation would be helpful since so many middle schools already have counseling resources on site. Also, it would be important to address the role of advocacy when neutrality is either impossible or undesirable.

Making the Peace

a. Description

This 180 page curriculum addressed violence prevention. The fifteen lessons were divided into three major sections. The “Roots of Violence” section introduced the concepts of violence and safety, led students to think about how violence affects their lives, and looked at the causes and cycle of violence. “Race, Class, and Gender: The Difference that Difference Makes” was designed to look at racial, gender, and economic factors in violence [1]. “Making the Peace Now” looked at the particular forms that violence takes as well as individual and group actions to make peace at the personal, interpersonal, and social level. Instruction was facilitated through group exercises, handouts, and role-plays. The curriculum goals included creating a caring and cooperative whole school environment, empowering students and teachers with skills necessary to resolve conflicts and developing responsible citizenship.

b. Strengths

The authors used the classroom experience as a communitybuilding experience enabling students to help each other to be safer and work for justice. The curriculum suggested how to assess the conditions in and around schools and students’ lives. Moreover, the text provided instructions on how to continue creating peace through discussion and study groups, support groups, advocacy groups, peer education, conflict resolution and mediation, and campus action. The curriculum presented a complex, structural approach to the issues of violence and youth. It grasped the underlying social and economic inequalities that are drawn across lines of race, gender, age, and sexual orientation, treating all issues with due complexity. Students were given the tools to address these challenging issues, contemplate solutions, and put their ideas into action. Additionally, the text was easy to follow and contained pragmatic, appropriate exercises. Involving students optimized the effectiveness of the program. Teachers were encouraged to facilitate the work of young people regarding these issues in an effective manner.

c. Limitations

Psychological content could be improved in a few ways. The use of problem-solving steps was suggested by reviewers. Theories of group dynamics could have been expanded. Less emphasis on how shields develop and more emphasis on here-and-now conflict resolution would be beneficial. Some constructs and/or assumptions also needed to be refined. For instance, constructs of “good” and “bad” were better described by peacemaking visions such as “opportunities taken” and “opportunities missed.” The curriculum implied that violence was a male trait that females emulate, and that violence is actually a human propensity that occurs when constructive means of communication fail. Lastly, the “exercise” assumed that everyone was good until scarred by others. Scars could also be attributed to a biological predisposition or environmental influences. More attention needed to be focused on the diverse nature of students using this curriculum. Some activities may leave students standing completely alone or may raise anxieties that they may be the only ones with a certain opinion, dissuading a student’s desire to contribute. The text seemed more appropriate for urban students than those from suburban or rural settings.

Productive Conflict Resolution

a. Description

b. The 474-page Curriculum and Teacher’s Guide Included

Lessons in Several Areas:

a. Building Community

b. Rules and Laws

c. Understanding Conflict,

d. Communication Theory

e. Listening Skills,

f. Expression Skills

g. Problem-Solving

h. Valuing Diversity

i. Forgiveness and Reconciliation

j. Media Literacy

k. Bully Victim Conflict

l. Putting it all Together

The key teaching strategies included role-plays, discussion, brainstorming, journaling, and other experiential learning. The curriculum was designed to develop part of a comprehensive school-wide conflict resolution plan through curriculum infusion and integration, classroom conflict resolution processes and teaching strategies, and peer mediation [16].

c. Strengths

The curriculum was comprehensive both in its conceptual underpinnings and practical applications. The major sections of the curriculum were broad and varied in focus. There was expansive exposure to the possible ways of communication toward the resolution of conflict. The importance of active learning and democratic involvement in the classroom were themes that ran through the lessons. There was attention to personal and group process opportunities to promote skill acquisition and integration. Additionally, there was an emphasis on self-evaluation to increase self-awareness. The format for lessons was very user friendly. Each unit began with an in-depth discussion of the topic followed by a specific lesson plan and closed with many excellent ideas and strategies for integrating the particular conflict resolution strategy into the academic curriculum. Goals, objectives, assumptions, and underlying concepts were clearly identified. The introductory section encouraged teachers to be sensitive to student needs and developmental readiness. Directions were easy to follow in this well-organized curriculum. There was a helpful appendix that contained interesting role-plays.

d. Limitations

Most reviewers perceived the curriculum as overly ambitious in scope. One third to one half of the lessons could be removed. Moreover, there was a lack of continuity between parts. The curriculum needed an overall model or framework that would help teachers and students organize ideas about the analysis of conflict and the problem solving approach. It was suggested that a more thorough explanation of the authors’ recommendations regarding the sequence of lessons be provided. The curriculum guide was organized by topic areas, but the authors recommend in the “schedule of lessons” a different sequence that can be confusing. Additionally, it would be helpful to see how teachers could be advised to be cross-curricular with each lesson plan and how to integrate work with other teachers. The lessons on valuing diversity were weak and fail to confront prejudice, hate, and discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. These problems should be addressed because they play such an important role in interpersonal and intergroup conflict. International issues were not addressed. The lessons in general were uneven in quality. Some were interesting and imaginative while others were of questionable educational merit. There appeared to be too much warm-up material about building community without sufficient focus to building specific skills such as identifying feelings or distinguishing between concerns or solutions. Reviewers expressed specific concerns about the lessons on anger, building community, conflict analysis, and discrimination as not being consistent with the psychological definitions and/or current research. Also, there appeared to be too much focus on cognitive aspects of psychological content and less focus on the emotional aspects. There seemed to be little consideration of how young adolescents may experience the issues that are covered. The curriculum emphasized talking and discussion, which can be challenging with this age group. Using educational and developmental principles could increase the likelihood that the curriculum would be effective. The quality of the teacher resources section was mixed. There was a lack of references to relevant research. It would be important to reference appropriate psychological journals and to provide a synopsis of each resource.

Viewpoints: A Guide to Conflict Resolution and Decision-Making for Adolescents

a. Description

The 23 page teacher guide and accompanying 102 page student manual included 10 lessons designed to teach social problem solving skills, increase impulse control, promote empathy, and develop prosocial attitudes. Much of the material was didactic, but interactive strategies such as role-playing could be used to increase group member participation. Each lesson involved reading and writing [17]. Lessons focused on problem identification, selfcontrol, bases of conflict, goal setting, generating alternatives, considering the consequences of actions, and evaluating results.

b. Strengths

This curriculum represented a good starting point to help sensitize students to their own values, ethics, choices, and responsibilities. The activities encouraged the heightening of problem-solving skills. This text could be viewed as a first step with the belief that individuals need to think about how to resolve conflicts individually before they could do it with others. The problem scenarios provided a wide range of common issues that adolescents faced with opportunities to contemplate, hear, and discuss a variety of problem-solving approaches. The 10 lessons beginning with “thinking about our problems” and continuing with “eight steps toward resolving them” fostered an organization of the skills required for students’ progress in learning to make sounder decisions. The objectives were clearly specified with examples and directions of tasks to accomplish. Psychological concepts were introduced in basic and simple language.

c. Limitations

This curriculum focused mostly on intrapersonal conflict rather than interpersonal or intergroup conflict. More emphasis was needed on working out conflict with others cooperatively and not strictly on how an individual could decide for himself how to solve a problem. Conflict resolution most often implies the former activity. Central elements of conflict resolution were presented in most lessons but not in any coherent way that readers could easily discern. There was a spareness of expository material regarding each section of the manual, which restricted the capacity of the curriculum to get across the importance of specific aspects of problem- solving and may impede the progress of the class in group exercises. The role of the teacher was unclear. There was also no mention of the importance of the including the entire school community and family in conflict resolution teaching. However, the curriculum would be much stronger if there was a more cogent discussion of each point being taught such as the essential cores of assertive stances to life or belief systems and how they affect behavior. Additionally, lessons did not include opportunities for repetition, practice, and feedback, which are essential for skill learning. The text did not take the opportunity to refer students to added appropriate reading in areas of communication, anger, assertiveness, and other relevant topics. Minimal attention was given to racial and systematic unfairness. More expository material was required in order to delineate prejudice more precisely and to discuss how valid judgments about people could be made.

Reviewers’ Ratings

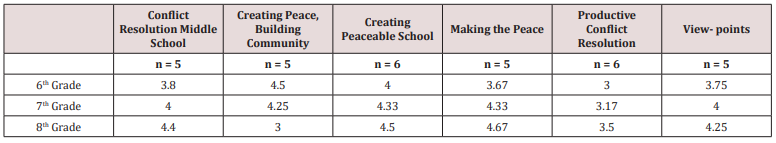

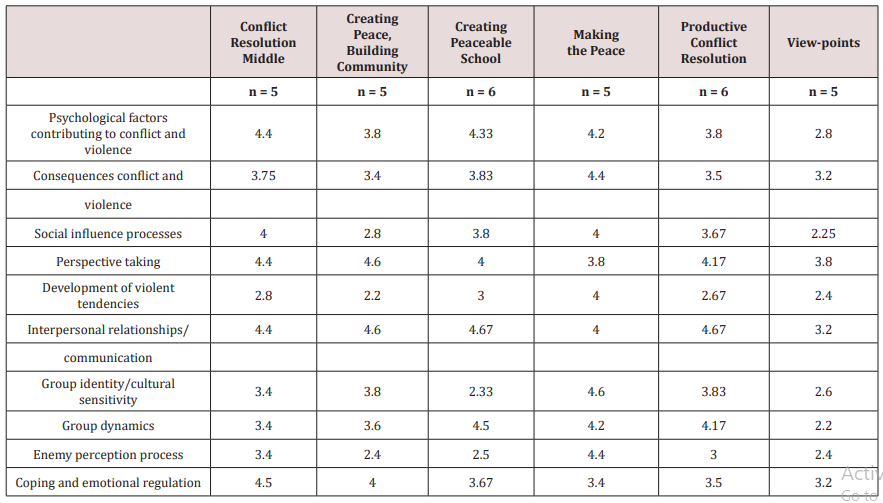

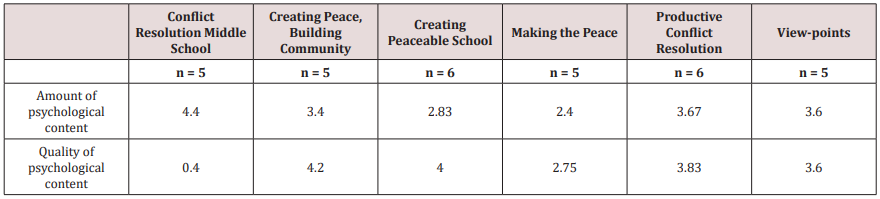

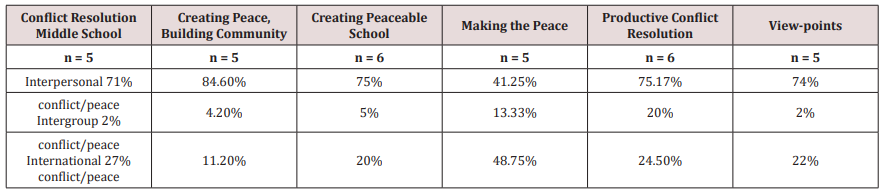

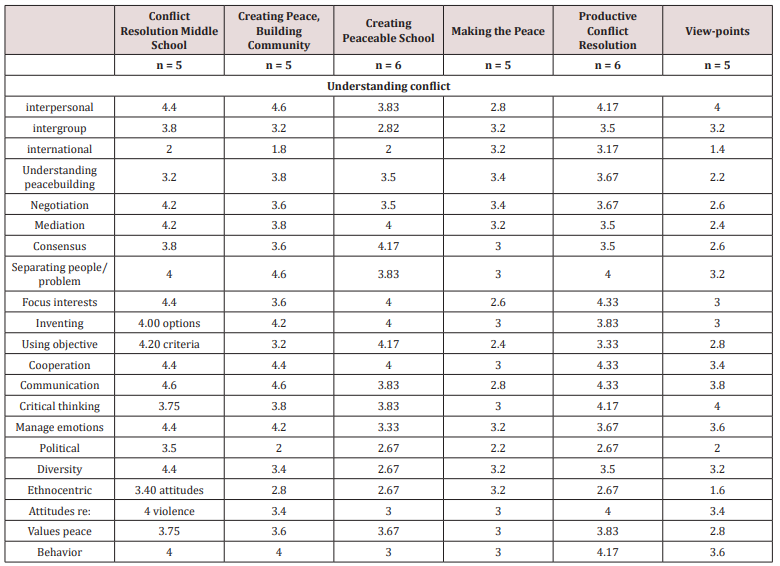

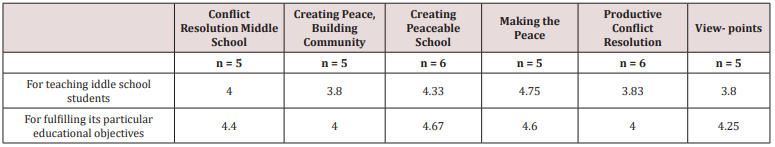

Reviewers appraised the probable influence of each curriculum on various educational objectives related to the development of peacebuilding and conflict resolution skills in middle school students. (Table 1) reported the mean reviewer ratings of the degree to which psychological concepts were addressed in the curricula. The results in (Table 1) showed some variability in the extent to which particular psychological concepts were addressed. Educators interested in utilizing curricula based on the sound use of psychological concepts should be advised to examine the curricula authored by [18]. The mean reviewer ratings of the adequacy of the amount and quality of psychological content within each curriculum have been reported in (Table 2). The results in (Table 2) again indicated the variability across the curricula. The Kriedler curriculum stood out as superior on these criteria. The means of the reviewers’ estimates of the percentage of the curricula devoted to interpersonal, intergroup, and international conflict and peace were shown in (Table 3). The results suggested that five of the six curricula provided an extensive focus on interpersonal conflict/ peace to the relative exclusion of content regarding intergroup conflict/peace. The Kivel and Creighton curriculum best addressed international conflict/peace. (Table 4) reported the mean reviewer ratings of peacebuilding. The results indicated some variability among the curricula. The Kriedler curriculum appeared to address the various skill areas most efficiently. The appropriateness of the curricula for different grade levels in the middle school was reported in (Table 5) as mean reviewer ratings. The results suggested that many of the curricula were better applied to older middle school students. Lastly, (Table 6) reported the mean reviewer ratings of the extent to which the curricula met the educational objectives in terms of teaching middle school students as well as fulfilling the particular educational objectives of the curriculum. The results indicated that all curricula met their objectives in both areas.

Table 1: Mean Reviewer Ratings of Psychological Concepts Addressed in Curricula.

Anchor points of Liker Scale: 1 = not utilized, 3 = utilized fairly well, 5 = utilized very well.

Table 2: Mean Reviewer Ratings of the Adequacy of the Amount and Quality of Psychological Content.

Anchor points of Likert Scale: 1 = very poor, 3 = satisfactory, 5 = excellent

N.B. Anchor points were modified from those utilized on the evaluation instrument to allow for consistency in the interpretation of scores across areas.

Table 3: Mean Reviewer Ratings of the Percentage of the Curricula Devoted to Types of Conflict and Peace.

Table 4: Mean Rating of the Curricula’s Influence on Developing Student Skills.

Anchor points of Likert Scale: 1 = none, 3 = some, 5 = considerable N.B. Anchor points were modified from those utilized on the evaluation instrument to allow for consistency in the interpretation of scores across areas

Table 6: Mean Reviewer Ratings of the Extent Curricula Met Educational Objectives.

Anchor points for Likert Scale: 1 = very poor, 3 = satisfactory, 5 = excellent N.B. Anchor points were modified from those utilized on the evaluation instrument to allow for consistency in the interpretation of scores across areas.

Discussion

The importance of peace education and conflict resolution curricula has been emphasized as a preventative oriented means of teaching students alternatives to conflict and violence as well as for promoting the skills, values, beliefs, and efficacy expectations involved in peacebuilding. Curricula have been identified as an integral part of a comprehensive approach that we advocate to influence change in the school community as well as the broader community over time. Middle school curricula should provide developmentally appropriate instruction in the area of thinking abilities and critical thinking abilities as proposed by [7]. Additionally, specific problem-solving methods (i.e. negotiation, mediation, consensus decision making) need to be taught to students using a variety of pedagogical techniques such as role playing, cooperative learning activities, and guided discussions with attention given to the needs of students for privacy and comfort in sharing information.

The six-peace education and conflict resolution curricula reviewed vary in the degree to which they accomplish these objectives and utilize these pedagogical techniques. The curriculum entitled Conflict Resolution in the Middle Schools was regarded by reviewers as taking a positive stance toward adolescents’ peacemaking and conflict resolution abilities, having high pedagogic standards, and being best at imparting guidance on the inclusion of colleagues and parents. It was also successful at conflict resolution instruction in the regular academic curriculum. Additionally, it provided helpful guidelines for teachers, supplied an opportunity for further teacher training, and furnished a comprehensive bibliography. Five of the curricula addressed interpersonal conflict while one (Viewpoints: A Guide to Conflict Resolution and Decision-Making for Adolescents) primarily focused on intrapersonal conflict. All six curricula failed to address intergroup and international conflict. Given that many middle school students learn about both intergroup and international conflict (e.g. the Civil Rights Movement, World Wars) in their academic classes, the lack of attention to these types of conflict represent a missed opportunity to infuse conflict resolution principles into the mainstream academic curriculum. Moreover, reviewers deemed that five of the six curricula reviewed inadequately developed their treatment of diversity issues and the influence of the underlying social and economic inequalities affiliated with race, gender, age, and sexual orientation. Since we live in a multicultural society, greater attention needs to be given to the collectivistic perspective and the barriers which many of diverse backgrounds face every day.

To date, none of the six curricula reviewed have been evaluated by outcome assessment studies. Several studies have examined the effectiveness of violence prevention curricula in middle school students. [19] compared the effectiveness of two violence prevention curricula among 225 middle school students. Results indicated that both curricula were successful in reducing indicators of violence. In a longitudinal study, the implementation of a violence prevention curriculum and the use of trained peer leaders had a significant effect on increasing knowledge about violence and skills to reduce violence in sixth grade students [20]. While these studies used curricula focusing on violence prevention rather than general curricula on peace and conflict, they point to the positive outcomes of use of curricula to meet educational objectives of peace education. Further evaluations of peace education, conflict resolution, and violence prevention curricula are warranted to continue to examine positive outcomes in middle school students.

Finally, and as noted in the previous study of peace education and conflict resolution curricula for high school students, curricula can be viewed as complementary and integrative rather than alternative options [1] Each can be a part of a comprehensive program at different points in time, e.g., from grade level to grade level. And again, we do advocate that peace education and conflict resolution curricula be implemented at all grade levels and as part of a comprehensive approach to peace education which includes such other aspects as peer mediation programs.

References

- Nelson L, Van Slyck M, Cardella L (1999) Peace and conflict curricula for adolescents. In Harris I, Forcey L (), Peacebuilding for adolescents: Strategies for teachers and community leaders. Peter Lang, New York, USA.

- Kuffner L (1999) Youth violence becomes focus for mental health legislation. Communique p. 40.

- Nation T (2003) Creating a culture of peaceful communities. International Journal of the Advancement of Counseling 25(4): 309-315.

- Ediger M (2003) War and peace in the curriculum. Journal of Industrial Psychology 30(4): 288-293.

- Levy J (1989) Conflict resolution in elementary and secondary education. Mediation Quarterly 7: 73-87.

- Maxwell J (1989) Mediation in the schools: Self-regulation, self-esteem, and self-discipline. Mediation quarterly 7(2): 149-155.

- Bodine R, Crawford D (1998) The handbook of conflict resolution education: A guide to building quality programs in schools. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, USA.

- Johnson D, Johnson R (1996) Conflict resolution and peer mediation programs in elementary and secondary schools: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research 66(4): 459-506.

- Van Slyck M, Stern M, Zak-Place (1996) Promoting optimal development through conflict resolution education, training, and intervention: An innovative approach for counseling psychologists. The Counseling Psychologist 24(3): 433-461.

- Van Slyck M, Stern M (1991) Conflict resolution in educational settings: Assessing the impact of Peer Mediation Programs. In: K Duffy, P Olczak, J. Grosch (Eds), The art and science of community medication: A handbook for practitioners and researchers, Guilford Press, New York, USA, pp. 257-274.

- Batton J (2002) Institutionalizing conflict resolution education: The Ohio Model. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 19(4).

- Crawford D, Bodine R (2000) Developing emotional intelligence through classroom management: Creating responsible learners in our schools and effective citizens for our world. Research Press, Champaign, Illinois, USA.

- Bodine R, Crawford D, Schrumpf F (1994) Creating the peaceable school: A comprehensive program for teaching conflict resolution. Research Press, Illinois, USA.

- Kriedler W (1997) Conflict resolution in the middle school. Educators for Social Responsibility, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Bachay J (1997) Creating peace, building community. Peace Education Foundation, Miami, Florida, USA.

- Colorado School Mediation Project (1997) Productive conflict resolution. Colorado School Mediation Project, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

- Guerra N, Moore A, Slaby R (1995) Viewpoints: A guide to conflict resolution and decision-making for adolescents. Research Press, Illinois, USA.

- Kivel P, Creighton A (1997) Making the peace. Hunter House, Alameda, California, USA.

- Du Rant R, Treiber F, Getts A, McCloud K, Charles W Linder (1996) Comparison of two violence prevention curricula for middle school adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 19(2): 111-117.

- Orpinas P, Parcel G, McAlister A, Frankowski R (1995) Violence prevention in middle schools: A pilot evaluation. Journal of Adolescent Health 17(6): 360-371.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...