Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Occupational Stress and Sleep Among Teachers: What is The Effective-Ness of A Programme to Reduce Occupational Stress Using Mindfulness? Volume 7 - Issue 1

Soraia Inácio1, Liliana Pitacho1,2,3, Ana Moreira1,4,5* and Carla Tomás 1

- 1Department of Psychology and Sports, Instituto Superior Manuel Teixeira Gomes, 8500-590 Portimão, Portugal

- 2Escola Superior Ciências Empresariais, Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal, Campus do IPS-Estefanilha, 2910-761 Setúbal, Portugal

- 3Centro de Investigação em Ciências Empresariais (CICE-IPS), 2914-503 Setúbal, Portugal

- 4School of Psychology, ISPA-Instituto Universitário, Rua do Jardim do Tabaco 34, Lisboa, 1149-041, Portugal

- 5APPsyCI-Applied Psychology Research Center Capabilities & Inclusion, ISPA-Instituto Universitário, R. Jardim do Tabaco 34, 1149-041 Lisbon, Portugal

Received:May 11, 2023; Published:May 18, 2023

Corresponding author: Ana Moreira, Department of Psychology and Sports, Instituto Superior Manuel Teixeira Gomes, 8500-590 Portimão, Portugal

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2023.07.000262

Abstract

In Portugal, teachers are subjected to numerous sources of pressure, which leads us to be a country with very high levels of occupational stress in this professional group. Occupational stress influences many aspects of the individual’s life, both personally and professionally, and mindfulness programmes have proved to be highly effective in reducing these symptoms, both personally and in the teaching profession, since there are studies that point to an improvement in the student-teacher relationship, with subsequent positive changes in the student’s academic performance. To bring some innovation to the programme to be applied in this study, physiological sleep measurement was added to the Stress and Mindfulness programmes, as this variable is related to stress, insofar as it is assumed that the higher the levels of stress, the lower the quality of sleep.

The present research aims to develop a mindfulness programme to be applied to a group of teachers intending to reduce occupational stress and try to understand to what extent occupational stress levels influence the quality and perception of teachers’ sleep quality. The results obtained indicate that occupational stress had a significant and negative effect on the quality of sleep at the first moment of assessment, namely in the overwork dimension, and that, after the application of the programme, the participating teachers showed lower levels of occupational stress, namely in the bureaucratic work, students’ motivation, overwork, and students’ indiscipline dimensions. Concerning the quality of sleep, the results did not show significant statistical differences; however, it was possible to identify differences in sleep quality between the assessment moments.

Keywords:Sleep; Occupational Stress; Teachers; Mindfulness Programmes

Introduction

Occupational stress results from the individual’s inability to cope with the sources of stress associated with his/her work context. This feeling of stress can generate physical, psychological, so cial, personal, and professional consequences for the individual, a psychological condition teacher in Portugal often perceives due to the various sources of stress associated with this profession [1,2]. The presence of these numerous sources of stress associated with the teaching profession makes it urgent to find coping strategies that help these individuals reduce their levels of occupational stress. In this sense, the use of contemplative practices through mindfulness has become more and more pertinent as a stress management tool. This concept is defined as a psychological process that offers a certain quality of attention to the experience of the present moment [3]. The literature review has revealed that mindfulness-based stress reduction programs have proven to be very efficient, helping to reduce participants’ stress symptoms [4-6].

Sleep is a complex and dynamic behavioural state necessary for the subject’s mental and physical recovery [7]. It is a physiological measure correlated with stress to the extent that, presumably, the higher the stress levels in individuals, the lower the quality of their sleep. Concerning the study of sleep quality, Kottwitz, et al. [8], when studying the quality of sleep in Swiss teachers through their perception, found that, of the 14 participants, 60.8% reported having a good quality of sleep and 39.6% of the participants reported having an average or poor quality of sleep. However, although some studies measure the quality of sleep through the participant’s perception of it, few include physiological measures to verify the reality of this perception evaluation. The present research aims, then, to understand the effectiveness of a Mindfulness programme on Occupational Stress, whose specific objectives are:

a) To develop and implement a mindfulness programme aimed at teachers in order to reduce their levels of stress;

b) To assess the perception of occupational stress and sleep, incorporating a physiological record that could prove the veracity of this perception, using an experimental group and a control group;

c) To verify if the perception of the quality of their sleep corresponds to the results obtained on the monitoring band.

This study aims to answer the following research question: “Does a Mindfulness Programme positively affect the levels of occupational stress in teachers and, consequently, influence their sleep quality?

The objectives of this research consist in verifying if the quality of sleep changes between the two moments of evaluation and if it changes between the experimental and non-experimental groups, as well as verifying if there is a decrease in the levels of stress of the programme participants after its application, verifying in a certain way, the effectiveness of the created programme.

Literature Review

Stress and Occupational Stress in Teachers

Stress is defined as an imbalance between the demands of the environment and the capacities/resources that the individual must adapt to them [9]. Despite its simple definition, the concept of stress is highly complex, and there are two models that best explain it: the biological model and the interactionist model. As regards the biological model, stress is defined as a physiological reaction of the body in response to a stimulus that threatens its balance - its homeostasis - and is divided into three phases: alarm (where the reactions caused by stress are considered as essential mechanisms for the body’s defence): resistance (where the body tries to adapt to the agents causing stress, operating in a state of hyper adrenaline and causing various symptoms such as anxiety, social isolation, nervousness, lack of appetite, among others) and exhaustion (where the responses triggered by the body as a form of defence are very similar to the responses triggered in the alarm phase, with only the intensity of the responses between these two phases being different) [10-12].

While the biological model points to the existence of several reactions of our body to stressful situations, the interactionist model points to the diversity of physical and cognitive reactions according to everyone’s experience of stress, i.e., according to this model, individuals respond in different ways to stressful agents, triggering, in turn, a cognitive response, the coping. In this sense, Folkman and Lazarus [13] define coping as strategies which have the potential to have a negative or positive impact on the physical and mental health of individuals, with the ability to modify or evolve stress symptoms, being widely used as a way to avoid or confront the situation causing stress. Therefore, and since this model considers the interaction between the environment and the individual as responsible for and participants in the process of stress and response to it, a new definition of stress emerged, which is still used today: stress is defined as any stimulus, internal or external, that puts to test the subject’s ability to adapt [12].

Occupational stress results from the individual’s inability to cope with the sources of pressure associated with his/her work context, which may have physical or mental consequences for him/ her. It encompasses a set of physical and/or emotional responses that are harmful to the human being and the organisation, arising from work demands that do not match the employee’s abilities, resources or needs, and, in this sense, it is seen as a negative problem in the individual’s life [1]. Being a teacher is a rewarding but very challenging profession, and it is considered a profession with highstress levels. The levels of occupational stress among the teaching staff in our country are incredibly high [2]. According to Santos et al. [2], teachers feel exhausted due to numerous factors associated with their profession, such as changes in educational policies, conflicts with students, conflicts with colleagues, the unpredictability of the profession if they substitute teachers or teachers with fixedterm contracts, and, more recently, with the pandemic situation and all the changes and adaptations that the educational context has undergone over this year and a half.

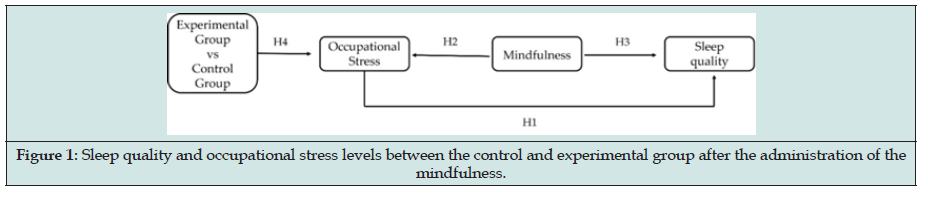

In addition to these factors that cause stress in the teaching profession, a recent study sought to verify Portuguese teachers’ psychological health and well-being. This study found that of the 1454 teachers in mainland Portugal when asked about the last two weeks before the evaluation, more than half said they felt nervous, sad, irritable, in a bad mood or wanted to give up because they felt they could no longer cope with it with some frequency during the week recently. When questioned about the week before the assessment, more than half of the teachers reported having felt some symptoms related to depression, anxiety and stress with some frequency, such as difficulty in relaxing, restlessness, overreacting in certain situations, feeling too susceptible or irritable, finding it difficult to take the initiative to perform tasks, feelings of sadness or depression, feeling that they were using too much nervous energy, and even difficulties in calming down [14] (Figure 1).

This difficulty in dealing with professional aspects of their career that lead to increased levels of occupational stress may subsequently result in decreased performance in their professional activity, higher levels of discouragement, job dissatisfaction, burnout, poor interpersonal relationships, lower perceptions of self-efficacy, and also negative psychological states such as depression, frustration, anger or physical discomforts such as headaches, psychosomatic symptoms, ulcers, among others [15,16].

Taking into account the difficulty in introducing substantial changes in the institutions or the education system to improve the teachers’ psychological well-being and, consequently, reduce the levels of occupational stress, it becomes increasingly relevant to control the effects of this disorder in teachers’ professional and personal lives, Through the creation and implementation of programmes to combat and prevent stress so that individual and/or group acquisitions are made, allowing this population to acquire skills that they can use in their daily lives [2]. When used with teachers, these programmes help them acquire the skills they need to overcome all the adversities that the teaching career provides them with. In addition, mindfulness practices among teachers can reduce stress and depression levels and, consequently, increase energy levels and emotional self-regulation [17-19].

Sleep

According to Danda et al. [20], sleep is one of the primary rhythms present in the individual, being produced by the action of different structures of the Nervous System and influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors to the individual. The extrinsic factors in this category include work schedules, leisure and other important activities for sleep and its quality and health [20]. Concerning sleep structures, it involves three primary subsystems: a homeostatic system which regulates the amount, duration and depth of sleep; a system responsible for the alternation between REM sleep (which is characterised by rapid eye movements) and NREM sleep (which is characterised by the absence of eye movements and is divided into four stages, increasingly organised according to the depth of sleep); and a circadian system which regulates the moment when sleep occurs and the subject’s alertness [21].

Sleep is thus defined as a complex and dynamic behavioural state which has an enormous influence on waking hours and contributes significantly to the mental and physical recovery of the individual. Furthermore, sleep is a precise barometer of the subject’s mental state. It is sensitive (sometimes even faster than other body systems) to tension and anxiety, playing a crucial role in immune and metabolic function, memory, and learning, among other vital human functions [7].

Occupational stress and sleep quality

The relationship between occupational stress and sleep quality is a bidirectional relationship since if occupational stress contributes to changes in sleep patterns and quality, sleep quality also contributes to changes in occupational stress levels. As sleep is essential for the recovery of biological functions, poor sleep quality corresponds to higher levels of occupational stress. According to several studies in Europe and Japan, occupational stress is associated with poor quality sleep, that is to say, occupational stress has a significant and negative association with the quality of sleep. In a study by Knudsen et al. [22] in the United States, poor sleep quality was positively associated with work overload, role conflict and repetitive tasks. Also, Shi, et al. [23] found a significant and negative association between occupational stress and sleep quality in a study of postal professionals in China. Sousa et al. [24] conducted a study with healthcare teachers. These authors concluded that although these teachers had low levels of occupational stress, there was a significant and positive correlation between occupational stress and the use of sleeping medications. They also concluded that daytime sleepiness, sleep disorders and sleep duration contribute most to poor-quality sleep.

The literature suggests that sleep health is altered by high levels of stress, in the sense that the greater the stress experienced by the individual, the lower will be his/her quality of sleep, and there is a strong correlation between high levels of stress and sleep disorders [14,25]. This is the reasoning that leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Occupational Stress has a significant and negative association with sleep quality at the first moment of assessment.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is defined by Jon Kabt-Zinn [3] as a psychological process that offers a certain quality of attention to the experience of the present moment, and it is necessary to learn to direct this attention to what we are initially paying attention to as the experience occurs, with an open mind, curiosity, and acceptance.

In addition to effectively reducing stress and anxiety, according to the literature review, mindfulness-based stress reduction programs have shown improvements in understanding, recognition, and emotional management, thus improving coping strategies and a greater perception of self-efficacy [6]. In addition to the benefits for the teachers themselves mentioned above [16,17,19], the use of mindfulness in this type of program shows benefits in the school context [26,5], especially improvements in the quality of teaching- learning, which also improves the student’s academic progress since their relationship with the teachers is improved, and they implement or try to reproduce in the classroom the techniques that they learn in these programs. In addition to this, we can also take into account other benefits, such as those that Fernández-Aguayo, et al. [4] revealed after the application of programmes using mindfulness: positive effects on the development of cognitive skills, namely in attention and concentration on specific tasks, psychoeducation, reduction of anxiety, depression and stress, as well as increased efficiency in information processing and an improvement in emotional regulation, thus showing that this type of programme has increasingly become an ally in the fight against or prevention of numerous symptoms and pathologies, and has become a field of research with considerable interest and demand [6].

Even so, regarding sleep and mindfulness, studies indicate that mindfulness practices are advantageous for improving sleep quality [27], since, according to Howell, et al. [28], mindfulness practices are related to sleep self-regulation since, according to the same authors, individuals whom recurrently practice mindfulness can better meet their body’s physiological needs through self-regulation, including the physiological need for sleep and to have physically and mentally restorative sleep. In order to put into practice the theory that mindfulness is, in fact, effective in improving the quality of sleep in teachers, a study conducted in Canada and the United States of America by Crain, et al. [27] found that mindfulness programmes are quite effective in terms of the quality and improvement of sleep since teachers who participated in the programme showed a decrease in mood swings and negative emotions in the workplace and their personal life and, consequently, an increase in positive emotions. In addition, this study also showed that, after participating in the programme, teachers experienced higher levels of work and personal satisfaction, as well as an increase in the quality and quantity of sleep during the working day and a decrease in insomnia and sleepiness symptoms during the day [27].

Despite studies focusing on the understanding of sleep and the effect of mindfulness on it, as previously mentioned, the reality is that only some of the existing studies focus on the Portuguese population. In this sense, this dissertation becomes relevant because, since we intend to create a programme using mindfulness to reduce the levels of occupational stress in teachers, we intend to assess the subjective quality of sleep through a questionnaire and also the objective quality through the use of bands that monitor the participants’ sleep one week before the programme begins and one week after the completion of the programme, in order to verify whether the individuals’ perception of the quality of their sleep corresponds to the authentic quality, as well as whether the programme helped to improve both the perception and the participants’ sleep. In this sense, and since the literature review indicates that occupational stress programmes significantly influence reducing stress among teachers, it is also expected to influence their perception of the quality of sleep since sleep and stress are related.

The following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 2: Mindfulness programmes significantly affect occupational stress, and it is expected that occupational stress levels will be significantly lower in the experimental group than in the baseline after the programme’s application.

Hypothesis 3: Mindfulness programmes significantly affect sleep quality, and it is expected that after the programme’s application, sleep quality in the experimental group will be significantly higher than in the baseline group.

Hypothesis 4: There are significant differences in sleep quality and occupational stress levels between the control and experimental group after the administration of the mindfulness program.

Method

Data collection procedure

Concerning data collection, permission had to be requested from the authors of the scales for their use in this research. An online questionnaire was created on the Google Forms platform, which was later shared with all teachers of the school cluster via institutional email. This questionnaire expressly guarantees the confidentiality of the answers. Participants were informed of their confidentiality during the questionnaire and the reason for requesting the parents’ first names and dates of birth (this information is requested from them to be able to match the answers of the first moment and second moment of the research), a reply of authorisation to complete the questionnaire, twelve questions for characterising the sample (mother’s first name, mother’s date of birth, father’s first name, father’s date of birth, gender, age, academic qualifications, length of service in the organisation, length of service in the post, employment relationship, cycle taught and interest in taking part in the programme) and two scales, one of Occupational Stress in primary and secondary school teachers and the other of Sleep Health. The initial data were collected from November 2021 to January 2022.

Registration for the programme was done through a Google Forms document where participants could register for the programme and send, through the institutional email, the programme schedule with the dates and sessions of the programme. The programme started on 30 March 2022, but due to the current pandemic situation and the rescheduling of sessions, it only ended on 25 M After data collection, a needs assessment was carried out to verify where the highest stress levels are found in the target population and to create the programme. After analysing the initial data, six sessions were created, each lasting around 1 hour, addressing various themes related to positive psychology, such as Stress and Mindfulness, Resilience, Task Management, Sleep and Sleep Hygiene, Communication, Teamwork and Conflict Management and Body Awareness, where the theme was discussed, and some activities were carried out.

As the programme also included a physiological sleep record, this was carried out one week before the programme started and one week after the end of the programme, together with the second stress assessment, to verify the differences between the two moments of assessment.

Study Design

This study is performed through an action-research, correlational, explanatory and retrospective study since the aim is to verify the programme’s effectiveness in reducing occupational stress and, consequently, the participants’ sleep quality. Thus, the concept of action research can be defined as a form of social research with an empirical basis. However, in comparison to the “traditional” research method, where only the part associated with theory (action) is included, this research method also incorporates the practical part (action), i.e., by conducting action research, we are associating theory with practice [29].

Participants

The sample was selected considering all professionals in the teaching career of a grouping of schools in Portugal with approximately 193 teachers, who were aged 21 years and over, as this is the minimum age for completing higher education to exercise this profession, and who participated in 4 or more sessions of the programme. The sampling process is non-random, intentional, and convenient since subjects were selected for their convenience to the research [30].

Regarding the program’s application, 11 initial enrolments were counted, but only seven teachers participated due to the exclusion criteria (participation in 4 or more program sessions). Thus, 71.4% of the participants were female (n = 5), and 28.6% were male (n = 2), aged between 39 and 59 years (M = 47.14, SD = 6.28). Concerning academic qualifications, 100% of the participants had a university degree (n = 7). Regarding professional activity, 42.9% belong to the Pedagogical Area Board (n = 3), 42.9% are hired/permanent (n = 3) and 14.3% belong to the Grouping Board (n = 1), with an average of 22 years of service in the area and two years at the service of this Grouping. As for the cycle they teach, 57.1% teach the second cycle (n = 4), 14.3% teach the first cycle (n = 1), 14.3% teach the third cycle (n = 1), and 14.3% teach Secondary education (n = 1).

The group of non-participants included seven teachers, 71.4% female (n = 5) and 28.6% male (n = 2), aged between 32 and 59 years (M = 45.86, SD = 9.10). Concerning academic qualifications, 85.7% have a bachelor’s degree (n = 6), and 14.3% have a master’s degree (n = 1). Regarding professional activity, 57.1% are contracted / fixed-term contract teachers (n = 4), and 42.9% belong to the Group’s Staff (n = 3), with an average of 20 years of service in the area and two years’ service in this Grouping. As for the cycle they teach, 57.1% teach the second cycle (n = 4), 28.6% teach Secondary education (n = 2), and 14.3% teach the third cycle (n = 1).

Data Analysis Procedure

The data were imported into SPSS Statistics 28 software to be processed. The first analysis was to test the internal consistency of each scale by calculating Cronbach’s alpha, whose value should vary between “0” and “1”, not assuming negative values [17] and being higher than .70, the minimum acceptable in organisational studies [32]. As for the sensitivity study, the different measures of central tendency, dispersion and distribution were calculated for the different scales used, thus carrying out the normality study for all items and the various scales. Hypothesis 1 was tested through multiple linear regression, hypotheses 2 and 3 through Student’s t-tests for paired samples and hypothesis 4 through Student’s t-test for independent samples.

Instruments

The Questionnaire of Stress in Primary and Secondary School Teachers (QSPEBS) evaluates occupational stress in primary and secondary school teachers. This assessment measure was adapted by Gomes and collaborators (2007) and had 27 items which are divided into six dimensions, namely:

1. Student indiscipline: teachers’ stress related to student behaviour problems and the difficulties experienced in managing indiscipline in the classroom.

2. Time pressures and overwork: teachers’ stress related to the lack of time for preparing lessons, the pressure felt to comply with the curricular plans, and the pressures felt related to overwork arising from professional obligations.

3. Students’ different abilities and motivations: teachers’ stress related to the different levels of learning in the classroom and the difficulty in establishing objectives that meet the needs of each student.

4. Teaching career: stress related to the different aspects of the teaching career

5. Paperwork: stress related to the bureaucratic and administrative obligations related to their professional career.

6. Inadequate disciplinary policies: stress related to the disciplinary policies at their disposal and the low acceptance of their authority and power

To assess occupational stress in this population, the QSPEBS consists of two parts. The first part assesses the overall stress levels in teachers on a 5-point Likert scale, with 0 beings “No Stress” and 4 being “High Stress”. The second part of the questionnaire includes 27 items corresponding to different sources of pressure that cause teachers’ stress. The items are answered on a five-point Likert scale, as in the first part of the questionnaire [33]. The values of the dimensions of this questionnaire are calculated by adding up the items of each dimension and then dividing the value by the total number of items that make up the dimension. This instrument has a good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .90 at the moment one and .88 at the moment 2. The Satisfaction Alertness Timing Efficiency Duration (SATED-PT) Sleep Health Scale aims to assess sleep health through participants’ self-report. The scale was validated for the Portuguese population by Becker, et al. [34] as part of a master’s dissertation assessing the five core dimensions of sleep, such as sleep satisfaction, alertness during waking hours, sleep timing, sleep efficiency and sleep duration.

The SATED-PT is composed of 6 items and is answered using a Likert-type scale where 0 corresponds to “Never” and 5 to “Always”, being calculated through the sum of the answers of all items and divided by the number of items in order to check the participant’s sleep health, and this value may vary between 0 (minimum value) and 5 (maximum value) [34]. This instrument showed poor internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .39 at the moment one and .60 at the moment 2. After removing items 3 and 5 at the moment one, Cronbach’s alpha value became .70. About moment 2, items 1 and 3 were removed, and Cronbach’s alpha value became .68.

Huawei Band 4 is a wearable physiological data collection device. Among the various data collected, the band features the Tru- SleepTM system that can extrapolate normal sinus rhythm and breathing signals from heart rate data. After being connected to the Huawei Health App using the Hilbert-Huang transform (HHT) method, the data is used to analyse the coherence and cross-spectral density of the two signals to allow for Cardiorespiratory Coupling (CPC) analysis, which can accurately determine (86.3%) which sleep state the individual is in (deep sleep, shallow sleep, REM sleep or wakefulness) inferring on its quality.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the variables under study

The first step was to perform descriptive statistics of the variables under study to understand the answers given by the participants. To this end, a t-student test was carried out for a sample. The results indicate that the participants revealed that they have stress levels above the central point of this scale (2), indicating high stress levels. These differences are statistically significant concerning overwork, career, and paperwork at time 1. At the time two, statistically significant differences are found in students’ indiscipline, overwork, career, bureaucratic work, and disciplinary policies (Table 1). The perceived quality of sleep is also significantly above the central point (2.5) at times 1 and 2. These results indicate that the participants have a poor perception of sleep (Table 1).

Hypothesis Tests

To test hypothesis 1, a multiple linear regression was performed after verifying the respective assumptions. Multicollinearity problems were detected in the dimension “students’ motivation”, which presented a tolerance value of .096 (lower than .200) and a VIF value of 10.46 (higher than 5). As such, this dimension is not considered in the following multiple linear regression analysis. The results indicate that only overwork significantly affects perceived sleep quality at time 1 (β = -.85; p = .006). The model explains 50% of the variability in sleep quality. The model is statistically significant (F (5, 8) = 3.63; p = .049) (Table 2).

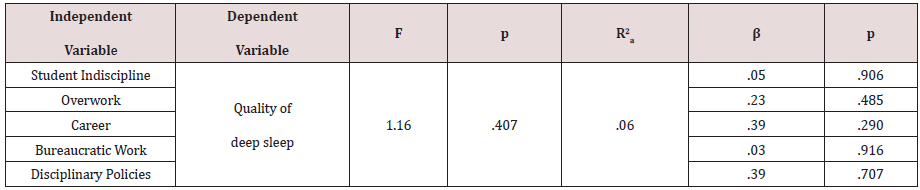

Then we studied the effect of occupational stress on deep and light sleep, measured by the Huawei Band 4.

The results indicate to us that none of the dimensions of occupational stress influences deep sleep measured before the programme. The model explains 6% of the variability in sleep quality. The model is not statistically significant (F (5, 8) = 1.16; p = .407) (Table 3).

The results indicate that only career (β = -.70; p = .043) and paperwork (β = .76; p = .006) significantly affect light sleep measured before the programme. The model explains the variability in sleep quality by 33%. However, the model is not statistically significant (F (5, 8) = 2.26; p = 0.146), so these results should not be considered reliable (Table 4).

This hypothesis was partially supported.

To test hypothesis 2, several Student’s t-tests for paired samples were performed after the normality assumption was verified. The results indicate to us that the programme did not have a significant effect on the stress levels of the participants. However, it was found that after participating in the programme, the effect of paperwork, student motivation, overwork and student indiscipline decreased in intensity. It should also be noted that the effect of career disciplinary policies on participants’ stress increased after the programme (Table 5).

This hypothesis was not supported.

To test hypothesis 3, paired Student’s t-tests were performed after checking the normality assumption.

The results indicate no statistically significant differences in the sleep quality perceived by participants between the moment before and after the mindfulness programme (Table 6). However, the participants’ sleep quality improved with the programme’s application. There were no statistically significant differences in the quality of deep sleep and light sleep measured by the band. However, it was found that the quality of light and deep sleep improved with participation in the programme.

To test hypothesis 4, several Student’s t-tests for independent samples were performed after the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were checked. Whenever the assumption of homogeneity of variances was not verified, the t-Student test with Welch correction was used. The results indicate to us that the group to which the participant belongs has a significant effect on paperwork (t (12) = 2.79; p = .008), student motivation (t (12) = 2.47; p = .029), overwork (t (12) = 2.91; p = .013) and student indiscipline (t (12) = 5.49; p < .001), with participants in the control group having higher levels than participants in the experimental group (Table 7).

The results indicate that there are no statistically significant differences in sleep quality, after the application of the mindfulness programme, between the participants of the control group and the experimental group participants (Table 7). However, we should mention that the participants in the experimental group were revealed to possess a better quality of sleep than the participants in the control group. As for the quality of sleep measured by the band, the experimental group participants were revealed to possess a better quality of deep sleep and a lower quality of light sleep than the control group participants.

This hypothesis was partially supported.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study aimed not only to create a programme to reduce stress and improve the quality of sleep that fully met the real needs of the target population but also to verify its effectiveness. Firstly, hypothesis 1 was partially proven since overwork significantly affects the quality of sleep of the participants. The higher the amount of overwork, the worse the participant’s sleep quality. These results are in line with what the literature tells us. Matos, et al. [14] say that sleep health is altered when faced with high-stress levels.

Regarding hypothesis 2, it was not confirmed, i.e. participation in the mindfulness programme did not significantly affect the participants’ stress levels. These results are not in line with what the literature tells us since, according to Santos, et al. [11], there are an increasing number of studies related to the effectiveness of mindfulness programs in decreasing stress levels in teachers. However, it was found that after participating in the programme, the effect of paperwork, students’ motivation, overwork, and students’ indiscipline decreased in intensity. It should also be noted that the effect of career disciplinary policies on the participants’ stress increased after the programme. These results are possible because the reassessment of occupational stress at the second moment coincided with the assessment tests’ application and correction and the school year’s end. We know that these moments are very stressful and anxious for teachers, which may compromise the quality of their sleep and, consequently, the results obtained after the program.

Concerning hypothesis 3, this was also not confirmed, as there are no statistically significant differences in the quality of sleep perceived by participants between the moment before and after the mindfulness program. It should be noted that the participants’ sleep quality improved with the programme’s application, both regarding the perceived sleep and the light and deep sleep measured by the band. These results are not fully in line with what Crain, et al. [8] tell us: mindfulness programmes are quite effective in the quality and improvement of teachers’ sleep.

Hypothesis 4 was partially confirmed since the participants in the control group showed higher levels of occupational stress than the participants in the experimental group (at time point 2) regarding the stress caused by paperwork, students’ motivation, overwork and students’ indiscipline. These results align with what the literature tells us: mindfulness programs reduce stress levels [6].

Limitations

In carrying out this action research, it is possible to identify some limitations. The first limitation is the fact that some participants dropped out of the programme halfway through the sessions, and 4 participants were removed from the list of participants through the exclusion criterion (participating in 4 or more sessions of the programme); the accuracy of the magnetic stripe monitoring, as I had feedback from some participants that the stripe monitored sleep in situations in which the participant was awake but at rest; the repetitive rescheduling of sessions due to school meetings or unforeseen situations; the results of the monitoring and reassessment of occupational stress at the second moment, since it coincided with the application and correction of the assessment tests and the end of the school year, which is a very stressful and anxiety-inducing moment for teachers, which may compromise their sleep quality and, consequently, the results obtained after the program; and, not having considered in the sociodemographic questionnaire the possibility of many teachers teaching different cycles at the same time, something that happens quite often in the Grouping where the study was conducted.

Suggestions for future research

As regards the suggestions for improvement, these would involve trying to circumvent the limitations presented somehow. Regarding the absenteeism of some participants, if this programme were to be applied again, it would be important to take into account the dates of the school breaks so as not to coincide with the application of the programme since some participants stopped coming to the sessions after the Easter break, It was also pertinent to schedule the sessions in dates where there were no meetings that could not be rescheduled, and that was very important for the teachers (such as pedagogical council meetings or end of term or school year meetings). If the same questionnaire were to be applied again to teachers, I would make the question on the cycle they teach with the possibility of choosing more than one cycle to obtain answers and results closer to reality. Concerning the accuracy of the band monitoring, there is no suggestion for improvement as it is a technological device, and we cannot predict how it monitors sleep. However, a possible explanation for this error in monitoring may be that when we are at rest, our physiological factors evaluated by the band may be very similar to when we sleep and, as such, the band cannot differentiate one state from the other and monitors it as sleep instead of rest.

Still, it would be pertinent to carry out this programme at another time of the school year. Since the programme was applied in the middle of the school year, it did not allow teachers to put all the techniques and tips provided into practice. If the programme were to be applied again, it would be pertinent to apply it at the beginning of the school year so that teachers could put into practice everything they had learned and acquired during the sessions and also so that the final stress evaluation would not coincide with times in the school calendar considered to be extremely stressful for teachers, since by applying for the programme at the beginning of the school year, the last evaluation would not coincide with stress-inducing events, making the final results more significant and providing better evidence of the programme’s effectiveness.

Final Considerations

Despite the limitations presented, it is possible to conclude that the programme created is effective and serves its effect and purpose. It is necessary to apply it at a time that does not compromise the research and at a time that allows teachers to apply everything they have learnt in a longer time than given. Even so, the results obtained exceeded the initial expectations and opened the door to the possibility of future research regarding the study of stress and sleep quality among Portuguese teachers, the replication of the programme and, consequently, its improvement so that it is possible to create a thoroughly effective interventional measure for this target population.

References

- Afonso JMP, Gomes AR (2012) Occupational stress in public service: a comparative study among employees of a local authority. In JLP Ribeiro, I Leal, A Pereira, A Torres, I Direito, P Vagos (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th National Congress of Health Psychology p. 14-21.

- Santos A, Teixeira A, Queirós C (2018) Burnout and stress in teachers: a comparative study 2013-2017. Psychology, Education and Culture 22(1): 250-270.

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990) Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte, USA.

- Fernández-Aguayo S, Rodriguez O, Miguel M, Pino-Juste M (2016) Effective Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction in Teachers: A Bibliometric Analysis. The International Journal of Pedagogy and Curriculum 24(1): 49-62.

- Thomas G, Atkinson C (2017) Perspectives on a whole class Mindfulness programme. Educational Psychology in Practice 33(3): 231-248.

- Carvalho H, Queirós C (2019) Burned out teachers: literature review on stress management programs with evaluation of effectiveness. Psychology, Education and Culture 22(2): 109-124.

- Akerstedt T, Nilsson P (2003) Sleep as restitution: an introduction. Journal of Internal Medicine 254(1): 6-12.

- Kottwitz MU, Gerhardt C, Pereira D, Iseli L, Elfering A (2018) Teacher's sleep quality: linked to social job characteristics?. Ind Health 56(1): 53-61.

- Guimarães IM (2019) Stress, a epidemia do século XXI - o que fazer para controlar? CUF.+Saúde CUF.

- Selye H (1959) Stress, the tension of life. São Paulo: Ibrasa - Brazilian Institution of Cultural Diffusion.

- Santos AM, Castro JJ (1998) Psychological Analysis 4(16): 675–690.

- Silva RM, Goulart CT, Guido Lde A (2018) Historical evolution of the concept of stress. Sena Aires Scientific Journal 7(2): 148–156.

- Folkman S, Lazarus RL, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen R (1986) Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive ap-praisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50(5): 992-1003.

- Matos (2022) Psychological Health and Wellness.

- Haydon T, Leko M, Stevens D (2018) Teacher Stress: Sources, Effects, and Protective Factors. Journal of Special Education Leadership 31(2): 99-107.

- Roeser R, Schonert-Reichl K, Jha A, Cullen M, Wallace L, et al. (2013) Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psy-chology 105(3): 787-804.

- Roeser RW (2016) Processes of teaching, learning, and transfer in mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) for teachers: A con-templative educational perspective. In K Schonert-Reichl & R Roeser (Eds.) The handbook of mindfulness in education: Emerging theory, research, and programs 133-149.

- Roeser RW, Skinner E, Beers J, Jennings PA (2012) Mindfulness training and teachers’ professional development: An emerging área of research and practice. Child Development Perspectives 6: 167–173.

- Skinner E, Beers J (2016) Mindfulness and teachers' coping in the classroom: A developmental model of teacher stress, coping, and everyday resilience. In KA Schonert-Reichl & RW Roeser (Eds.) Handbook of mindfulness in education: Integrating theory and research into practice 99-118.

- Danda G, Ferreira G, Azenha M, Souza K, Bastos O (2005) Sleep-wake Cycle Pattern and Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Medical Students. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria 54(2): 102-106.

- Carrillo-Mora P, Ramirez-Peris J, Magana-Vazquez K (2013) Neurobiology of sleep and its importance: an anthology for the university student. Magazine of the Faculty of Medicine 56: 5-15.

- Knudsen LB, Kiel D, Teng M, Behrens C, Bhumralkar D, et al. (2007) Small-molecule agonists for the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(3): 937-942.

- Shi H, Gazal S, Kanai M, Koch EM, Schoech AP (2021) Population-specific causal disease effect sizes in functionally important regions impacted by selection. Nat Commun 12: 1098.

- Sousa LMM, Firmino CF, Marques-Vieira CMA, Severino SSPS, Pestana HCFC (2018) Reviews of the scientific literature: types, methods and applications in nursing. Portuguese Journal of Rehabilitation Nursing, 1(1): 45-54.

- Galvão AM, Pinheiro M, Gomes MJ, Ala S (2017) Anxiety, stress and depression related to sleep-wake disorders and alcohol consumption in higher education students. Portuguese Journal of Mental Health Nursing (5).

- Jennings PA, Brown JL, Frank JL, Doyle S, Oh Y, et al. (2017) Impacts of the CARE for Teachers Program on Teachers’ Social and Emotional Competence and Classroom Interactions. Journal of Educational Psychology.

- Crain TL, Schonert-Reichl KA, Roeser RW (2016) Cultivating teacher mindfulness: Effects of a randomized controlled trial on work, home, and sleep outcomes. J Occup Health Psychol 22(2): 138-152.

- Howell AJ, Digdon NL, Buro K (2010) Mindfulness predicts sleep-related self-regulation and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 48(4): 419-424.

- Fonseca K (2012) Action Research: A Methodology for Teacher Practice and Reflection. Onis Science Magazine 1: 1-2.

- Marôco J (2021) Statistical analysis with SPSS Statistics (8ª edição). Pêro Pinheiro: Report Number, Lda.

- Hill M, Hill A (2008) Questionnaire Investigation. (2ª Ed) Lisbon: Syllable Editions.

- Bryman A, Cramer D (2003) Data analysis in Social Sciences. Introduction to Techniques Using SPSS For Windows, Oeiras: Celta (ed).

- Gomes AR, Montenegro N, Peixoto AB, Peixoto AR (2010) Occupational stress in teaching: A study with 3rd cycle and secondary school teachers. Psicologia & Sociedade 22(3): 587-597.

- Becker NB, Martins RIS, de Neves Jesus S, Chiodelli R, Rieber MS (2018) Sleep health assessment: a scale validation. Psychiatry research 259: 51-55.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...