Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Locus of Control and Vulnerability to Peer Pressure: a Study of Adolescent Behavior in Urban Ghanaian Context Volume 4 - Issue 1

Manuela Julietta Amorin1* and Desmond Ayim Aboagye2

- 1Graduate from the Psychology Department, (BS) Regent University College of Science and Technology Accra, Ghana

- 2Dean of Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Regent University College of Science and Technology Accra, Ghana

Received: April 21, 2020; Published: April 28, 2020

Corresponding author: Manuela Julietta Amorin, Graduate from the Psychology Department (BS) Regent University College of Science and Technology Accra, Ghana

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2020.04.000177

Abstract

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

Peer pressure is one thing that every individual is vulnerable to and has faced before at some point in their lives. It is becoming a serious health problem, especially for adolescents as well as concerned parents because, though not all peer pressure leads to health-related concerns or is negative, most are that need curbing, or treatment. Thus, NGOs, youth organizations, social welfare as well as parents, are looking for different ways to tackle this health-related issue in society. This research investigated locus of control on vulnerability to peer pressure in the African context. A survey was conducted using 144 adolescents from 2 Senior High Schools in Ghana with ages ranging from 15 to 19 years old. The following data collection instruments were used: Informed consent, Demographic data which used to group the students into categories based on age, class form and gender; the Nowicki-Strickland test (1973) and the Steinberg and Monahan resistance to peer influence scale (2007) measuring Locus of Control and Resistance to Peer Influence respectively. Statistical methods such as the independent t-test and Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient (Pearson r) were used to study the relationships between age, locus of control, and resistance to pressure in the urban context. The findings revealed that there was no significant effect of locus of control on vulnerability to peer pressure, which still indicates that our study may be more bent towards the general idea that individuals with an internal locus of control are more likely to resist the pressure to conform by their peers.

Keywords: Adolescents; Locus of control; Peer Pressure; Health problems; Internal and External locus of control; Resistance

Introduction

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

Background of the study

Peer pressure also known as social pressure refers to the pressure to behave differently that is exerted by peers [1]. Peer refers to same aged friends who share same activities [2]. Peer groups are considered to have significant influence on adolescents in that most teenagers prefer to do things their peer groups suggest they do. The prevalence of smoking increases dramatically during adolescence [3]. It should be noted that not all peer influence is bad [4-7]. Organizations such as Red Cross use peer educators to teach teenagers about safe sex because they have found that teens are more likely to listen when the positive messages come from those in their age groups. Susceptibility to peer pressure can be linked to several factors, including the level of persuasive skill of the influencer, the perceived authority of influencer as well perceived degree of choice by the individual, amongst others. Locus of control is a concept that was brought to light in the 1950s, and it is defined as people’s very general, cross-situational beliefs about who or what has control over the outcome of events in their lives [5,3]. Individuals are classified under having either internal or external locus of control, where those with internal locus of control, also called internalizes, believe that they have control over their lives as opposed to individuals who have external locus of control (externalizers) who believe that external forces such as luck and chance determine the outcome of events in their lives and they have no control over these forces [8]. These tendencies characterize a person’s perspective about self-independence and influence over others [9]. A study by [10] showed that their aggressive peer groups influence men with external locus of control in a way that promotes intimate partner aggression (IPA). There is proof in terms of research showing a link between peer pressure (social pressure) and locus of control.

In some cases, people can resist the pressure to conform or obey because of their personality. For example, research supports the idea that individuals with an internal locus of control are more likely to resist social pressure [11]. Rotter’s locus of control to determine whether the locus of control is linked to conformity. Using 157 students, he concluded that individuals with a higher external locus of control (externalizers), are more likely to conform as compared to internalizes. According to an article published by the Canadian Lung Association (2016), “my friends smoke” and “I thought it was cool” are two of the main reason’s individuals between the ages of 12 and 17 start smoking. They also found that 70% of teens who smoked have friends who smoke or started smoking because of peer pressure. A study in Ghana by Bingenheimer suggests that the desire to impress friends or conform to perceived peer norms may be an essential driver of sexual initiation among young people, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Statement of Problem

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

Peer pressure influences teenagers to do things they would not normally do, most of which are negative and, in some cases, go against the moral upbringing of adolescents. Research shows that it is at this stage in life that individuals experience first-hand peer pressure and are more susceptible to succumb to it. If they do not conform, they are ridiculed. If they yield to the pressure, they are labeled as “cool” among their peers, and these “cool” teens also enjoy a sense of belonging. Such early indulgence in deviant acts can affect a youth for the rest of his or her life. There has been little research done in Ghana with respect to adolescents and peer pressure [12-15].

Purpose of Study

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The purpose of the study is to investigate the effect of locus of control on resistance to peer pressure in adolescents. The study seeks to find out whether the type of locus of control a person has be it internal or external, has any influence on the person’s level of resistance to resist peer pressure.

Objective of Study

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The study aims to examine the relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure among adolescents in senior high schools in Ghana and also add to the small body of research existing with data covering the relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure among adolescents in Ghana.

The specific objectives

a) To examine whether female students with an internal locus of control are more likely to resist peer pressure.

b) To determine if there is a positive relationship between sex, locus of control and resistance to peer pressure

c) To examine if there is a relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure.

d) To enquire if males with external locus of control are more likely to resist peer pressure as compared to females with external locus of control.

Research questions

a) Are female internalizers more likely to resist social pressure?

b) Is there a positive relationship between older adolescent internalizers and resistance to social pressure?

c) Are there gender differences among externalizers with resistance to social pressure?

d) Is there a link between locus of control and resistance to social pressure?

Statement of hypothesis

a) Female students with an internal locus of control are

more likely to have a higher resistance to peer pressure than

their male counterparts.

b) Male adolescents are more likely to have a higher

resistance to peer pressure scores than female adolescents.

c) There is a positive relationship between locus of control

and resistance to peer pressure.

Significance of study

This study will provide ideas about how locus of control can influence resistance to peer pressure and identify the type of locus of control that has a high resistance to peer pressure. This knowledge will help educators, parents, and all interested persons to be able to design interventions to aid adolescents in resisting social pressure/peer pressure. This study seeks to also encourage individuals to conduct more research in this area as well as others with respect to the Ghanaian population.

Delimitation of study

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The population of interest consists of 150 students between the ages of 13 and 19 years.

Limitation of study

The following limitations characterized the study. Due to the sensitivity of the information the researcher was looking for, participants may have provided socially desirable responses despite measures taken during data collection to ensure privacy and confidentiality of the information shared by participants. Also, the study was conducted only in selected schools in the Greater Accra region and the findings may not be representative enough to reflect the cases in the entire country, hence they cannot be generalized. In addition, the survey was executed within a school setting, which eliminates the responses of adolescents outside school.

Operational Definition of Terms

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

Peer pressure

a) For this study, peer pressure, also known as peer influence or social pressure, refers to the influence by peers to indulge in unhealthy and wrong behaviors such as drug use, pre-marital sex, amongst others.

b) Locus of control.

c) This refers to the degree to which a person believes he or she has control over the outcomes of events in their lives. It has two categories:

d) Internal locus of control, where individuals believe they have control over the outcome of events in their lives, and their lives as a whole.

e) External locus of control is where individuals believe they do not have control over the outcome of events in their lives and their lives as a whole is ruled by chance or some other uncontrollable force. Resistance.

f) Resistance signifies a person’s ability to not conform to the pressure exerted by peers to act or behave in a way contrary to their will.

g) Adolescents.

h) Adolescents in this study refer to individuals between the ages of 13 and 19 years old.

Theoretical Framework

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

Erik Erikson’s theory on psychosocial development

According to Erikson (1950), every human being goes through

a developmental crisis at each stage of his/her life. Erikson came up

with 8 stages at which we face a developmental crisis. His second

stage, autonomy versus shame and doubt, occurs between the ages

of 18 months and approximately age 2 or 3, and at this stage, the child

struggles with autonomy and guilt. Erikson explained autonomy as

a sense of independence [16-20]. If the child is successful in this

stage, he achieves a sense of autonomy; he believes he has control

over physical skills and a sense of independence. Failure leads

to a feeling of doubt in one’s abilities and competence. Erikson

proposes that parents allow their children at this stage to explore

the limits of their abilities within an encouraging environment,

which is tolerant of failure. The aim is to be “self-controlled without

a loss of self-esteem”. If the child feels encouraged and supported

in his independence, he becomes confident and hopeful as well as secured in his abilities to survive in the world. A study involving

29 males and 79 males taking the following tests, the 1986 Miller

Hope Scale, Beck’s 1988 hopelessness Scale, Erikson’s psychosocial

stage inventory, Levenson’s 1972 locus of control scale and rating

their present state of hopelessness on a 10-point scale. They found

that a lack of hope correlated positively with the belief that external

forces control the events in one’s life, that is, external locus of

control. This suggests that infants who are not successful in this

stage of Erikson’s development are more likely to be externalizers.

Also, Erikson’s third stage of psychosocial development initiative

versus guilt [21,13].

According to Erikson, this occurs between the ages of 3 to 5. At

this stage, children assess themselves more frequently. In this time,

the primary feature involves the child regularly interacting with

other children at school. Play is essential in this stage as it provides

children with the opportunity to explore their interpersonal skills

through initiating activities. If children are given the opportunity

to initiate their activities, they develop a sense of initiative and

feel secure in their abilities to lead and make decisions. If they are

restricted, they develop a sense of guilt. They tend to prefer being

followers and lack self-initiative. [20] he found out that success in

3 of Erikson’s stages, including stage 3, is linked with an internal

locus of control [22].

Social Learning Theory

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The social learning theory, as proposed by [11], represents a

combination of learning and personality theories. According to

[6], individuals before exhibiting a behavior consider the possible

outcomes of that behavior and act on their beliefs. The relationship

is symbolized by BP = E+RV with BP being behavior potential, E

being expectancy, and RV being reinforcement value. The theory is

compromised by 4 variables:

a) Behavior potential refers to the probability that an

individual will act in a specific fashion relative to alternative

behaviors.

b) Expectancy is the individual’s belief concerning the

likelihood that a specific reinforcement will occur as a

consequence of a particular behavior.

c) Reinforcement value refers to how much the individual

values a particular outcome relative to other potential

outcomes.

d) The psychological situation implies that the context of

behavior is important. How the individual views the situation

can affect both reinforcement value and expectancy.

His theory differs from the behaviorist’s social learning theory

in the sense that according to [6], what drives a person’s behavior

is not merely the environmental reinforcement but rather what

the person thinks about that particular reinforcement [23-25]. He developed his theory of locus of control based on these concepts.

This theory, therefore, suggests that locus of control can be learned

based on the person’s beliefs about what causes a particular

outcome or reinforcer [26-32].

Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

While conducting a classical conditioning experimental research accidentally discovered the theory of learned helplessness. They noticed how the dogs that had received unavoidable electric shock failed to act in following situations, even with those with which avoidance was possible. The study was replicated with humans using loud noise in place of the electric shock [6,11]. They proposed the term learned helplessness to describe the expectation that outcomes are uncontrollable [12]. Evidence has supported that locus of control affects learned helplessness. all had similar results indicating that individuals with an external locus of control exhibit a higher level of learned helplessness as compared to individuals with an internal locus of control.

Conceptual

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

This section of chapter two deals with the main variables of the

present study and how it influences resistance to peer pressure,

which is, how locus of control influences resistance to peer pressure.

Locus of control refers to the general and cross-situational beliefs

of individuals about who or what has control over the outcome of

events in their lives [17]. There are only two dimensions of locus

of control. One is either an internalizer, which is having an internal

locus of control or an externalizer, having an external locus of

control. Individuals with internal locus of control generally believe

the outcome of events in his/her life is determined by his/her hard

work, attributes, or decisions. On the other hand, individuals with

internal locus of control believes that the outcome of events in his/

her life is out of his/her control and is determined by “fate”, or luck

and is independent of his/her hard work or decisions. For instance,

in a situation where an individual fails an exam, if the individual

has an external locus of control, he/she may pass comments like

“I didn’t study enough that’s why I failed”, whereas if he/she has

external locus of control he/she may pass comments such as “the

lecturer doesn’t like me that’s why he failed me”.

Several factors influence the development of a person’s locus

of control. For instance, the inability to achieve autonomy during

childhood development is linked with an external locus of control

[12,5,8]. Also, success in achieving initiative during childhood

development is linked to an internal locus of control [9, 23]. From

understanding what locus of control is, one would easily think

or expect it to influence an individual’s ability to resist pressure

from peers, and research does, in fact support it [11]. Due to the

characteristics of internalizers, yielding to peer pressure is not

likely though not impossible as compared to a higher chance of

yielding to peer pressure by externalizers.

Review of Empirical Data

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

This part of the chapter looks at the works of other researchers on the topic or similar areas. It is vital to compare research findings to come to a better understanding of the relationship between the main variables of the issue of concern. The empirical review will be done under three sub-sections, namely: Gender and peer pressure, Age and resistance to peer pressure, the relationship between locus of control and peer pressure, as well as gender and locus of control.

Gender and Peer Pressure

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

Several studies indicate gender differences in the extent to which adolescents are affected by peer pressure. In a retrospective study [16] to determine the pressure peers exerted in various aspects of high school and how said pressure influences teenager’s attitudes and behaviors. In 297 college undergraduates, found that about 33% of the students experienced peer pressure and identified it as one of the hardest things they had to face. Besides finding that peer pressure was most influential for females, [4] realized the participants answered were not in harmony as to which areas peer pressure was strongest. [5,18,16] study involving 620 participants (46% females and 54% males) showed that conventional peer characteristics strongly influence intrinsic motivation. According to them, “conventional peer characteristics refer to behaviors that are considered positive or socially acceptable”. For example, an adolescent will have a strong intrinsic motivation to smoke, practice unsafe sexual activity, cheat during an exam if his/her friends endorse such behaviors.

Moreover, their results showed that the positive relationship between intrinsic value and conventional peer characteristics was stronger in females. Thus, females will feel a stronger intrinsic urge to indulge in activities their peer validate as compared to their male counterparts whose intrinsic motivation is not as affected by the same. This finding, therefore, highlights gender differences in peer pressure. The conventional peer pressure characteristics and negative peer orientation (NPO) issues assessed by [15] contained 6 and 4 items respectively which dealt with adolescent performance in school and breaking parent’s rules. There was a significant relationship between the NPO and the grade point average (GPA) of adolescents (r= .16, p<.01), it was concluded that the difference in how each gender is affected by peers can be attributed to social and behavioral pressures exerted by a desire to conform to gender role norms. Contrary to the above studies, Steinberg and Silverberg (1986)’s study involving 865 10-16 year olds in grades 5 (N=209), 6 (N=215), 8(N=231) and 9(N=210) in the Madison Unified School District from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds. The participants completed a questionnaire battery assessing three aspects of autonomy–emotional autonomy in relationships with parents, resistance to peer pressure, and the subjective sense of self- reliance. Results showed females at all age levels had a higher score in all three measures of autonomy contrary to the notion about astonishing levels of autonomy in adolescent males.

Age and resistance to peer pressure

It is believed amongst developmental psychologists that in adolescent years, individuals are more influenced by peers than by parents. However, according to researchers, this occurrence is influenced by the type of behavior concerning the individual being influenced. A study involving 398 11-year olds and 449 14-year olds classified as pre-adolescents and adolescents respectively aimed at examining the influence parents had on children smoking behavior in comparison with the influence peers had on the same behavior. The results validated the belief that peers have more influence on each other than parents do [3,17]. In an investigation with similar results, [11] investigated changes in development with respect to conformance with parents and with peers as well as the relationship between both. This investigation was conducted in two parts. The first part (Study 1) involved 251 children from multiple grades responding to hypothetical situations where peers urge the child to engage in some specific behaviors. The second part of the study (study 2) involved 273 children from multiple grades as well. In this instance, the participants responded to situations that aimed at investigating conformance to peers on “antisocial and prosocial” behaviors and conformance to parents on “prosocial and neutral” behaviors.

Results from both parts of the study showed that in the 9thgrade peer conformity was at its highest. Conformity to parents was on a decrease as age increased. However, it is good to note that not all measures showed a negative correlation between conformity to peers and conformity to parents. Just as the results from the research above as well as others show an inverted U pattern with respect to adolescents and conformity to peers, a study on age differences in resistance to peer influence showed a peak between the ages of 14 and 18 with respect to peer conformity as compared to other age groups [21]. This study comprised a total of 3,600 males and females with ages ranging from 10 to 30. The study took the form of one longitudinal and two cross-sectional studies. All are concluded that mid-adolescence was the period an individual developed his or her autonomy over their behaviors as opposed to engaging in a behavior as a result of peer conformity.

The relationship between resistance to peer pressure and locus of control

General research supports that individuals with an internal locus of control are more likely to resist pressure from their peers. Undertook a study using the qualitative method in collecting their data. Of the 532 non-Jewish survivors of World War II who participated in the study, results showed that 406 of them were likely to have a higher internal locus of control as compared to the 126 who “simply followed orders”. The results were obtained by comparing those who identified as resisting orders against the Jews and those who did not. Though it is strenuous to conclude that locus of control was the sole factor that influenced their decisions, the results of the study do suggest that internal locus of control causes an unlikelihood to follow orders. Furthermore, [6], in determining if locus of control is linked with conformity, assessed 157 undergraduates using Rotter’s locus of control scale. In support of findings, [6] found that individuals who identified with a high internal locus of control were less likely to conform. However, he tested locus of control across normative and informational social influences, and although his results did not show any difference with informational social influence, it appeared that in instances of normative social influence there was a negative correlation with internal locus of control. That is to say, individuals with an internal locus of control do not conform in order to “fit in”.

Gender and locus of control

In West Scotland, with the aim of determining gender

differences in locus of control in terms of alcohol dependency,

a study was conducted using 108 participants from alcohol

dependence treatment centers. With the multidimensional health

locus of control form-C as the test tool for locus of control and

independent t-test as the analysis. Results yielded women having

higher internal locus of control as compared to men. There is

however, no statistical significance in this finding. Contrary to

[14,17], however, [22] had results from their study; involving 281

adolescents aged between 14-18 years; showing that males score

higher with respect to an internal locus of control than females did.

Their study aimed at gender differences in locus of control. It could,

however, be debated that this contrast is a result of the differences

in age groups used for each study.

In another study on the gender differences in taking

responsibility for academics, administered the Intellectual

Achievement Responsibility (IAR) on 425 school children. Results

from the study showed that females scored higher in internal locus

of control with respect to success and failure outcomes however,

only at the end of the school year. Females also echoed success as

a product of effort a lot more than males. Researchers of the study

nonetheless pointed out that gender differences though present,

were small. In sync with findings of gender differences in locus of

control from [16,7,13] in their search on the relationship between

locus of control, level of ability and gender, using 14 and 15 year old

Norwegian students found that females had notably higher internal

locus of control scores than males.

Summary of empirical review

In summary, there seem to be conflicting results as to which gender resists pressure more as well as what age stages influence resistance to social pressure. Furthermore, with gender and locus of control, females appear to score higher on internal locus of control scores as compared to males. However, there have not been extensive studies done with respect to the link between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure.

Methodology

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

This chapter of the study considers the research methodology as well as the procedures that were used to identify the link between the variables of the study. It will include the research design, population, sampling methods, procedures for data collection, measures of instrumentation, ethical consideration as well as data analyses.

Research design

This study used a cross-sectional survey that was designed to identify the effect of locus of control on resistance to peer pressure among senior high school students in Accra.

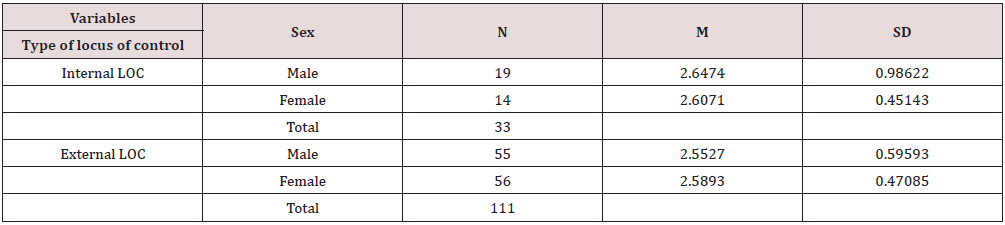

Population

The target population for this study was adolescent students in senior high school in Accra. The specific target population was students in 2 selected senior high schools namely: Tema Secondary School and Labone Senior High School. The schools were chosen out of convenience to the researcher in terms of cost and distance. It includes students from all three forms (Tables 1-4).

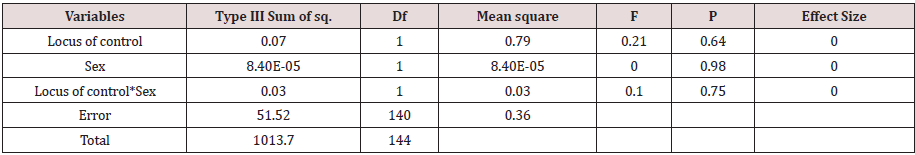

Table 2: The summary of the 2-way ANOVA comparing sex, locus of control and resistance to peer pressure.

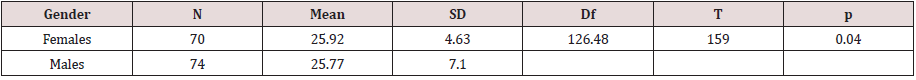

Table 3: The summary of the independent t- test comparing females and males on scores of resistances to peer pressure scale.

Sample and sampling techniques

With respect to sampling, an element is the person or object about which or from which the information is being collected [2]. This begins by first identifying a specific target group. The sample for this study was derived from two senior high schools namely: Tema Secondary School and Labone Senior High School. The sample consists of 150 participants both males and females in SHS 1, 2 and 3. The researcher used a random sampling method. Described simple random sampling as a process whereby a subject is drawn from a population in such way that each member of the population has the same opportunity of being selected for inclusion in the subset as all the others (Figure 1).

Instrumentation

The research instrument was divided into four (4) sections: Informed consent, Demographic data (which was used to group the students into categories based on age, form and gender); and the Steinberg and Monahan resistance to peer influence scale (2007) measuring Locus of Control and Resistance to Peer Influence respectively. Responses for the resistance to peer influence scale was ranked on a four-point Likert scale of “really true for me, sort of true for me, really true for me and sort of true for me” whereas responses for the locus of control test was ranked on a five-point Likert scale of “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “not sure”, “agree”, “strongly agree” . Piloting of the tools, for resistance to peer influence test as well as locus of control scale was done among adolescents (N=26) in different senior high schools who were not part of the initial population. The tools used were already existing ones that have been used before but to determine if items in both tools were understandable to the participants a pretesting had to be done. The results of the piloting showed that generally, the items in the test as well as instructions were understood by participants. Out of the 150 questionnaires distributed to the participants, all but 6 were fully completed, hence the response rate for this study was 96%. There were no signs of psychological, emotional, or other form of distress after the exercise hence debriefing wasn’t deemed necessary by the student.

Validity and reliability

Defined validity as the degree to which a measurement corresponds to the construct that was supposed to be observed. Simply, it is the extent to which a questionnaire accurately measures what it was designed to measure. Both questionnaires had good validity coefficient ranging from .55 to .75 and .52 to .80, respectively. Reliability refers to a measure’s stability or consistency across time. If used on the same stimulus, a reliable construct gives approximately the same results each time it is used for an instrument’s data to be used in a study meaningfully that instrument must be reliable. Using the Cronbach Alpha equation to test for the reliability of the resistance to peer pressure and locus of control scale, a result of .681 and .801, respectively.

Data analyses procedure

The first data collection section of the study which was the demographic data section was analyzed using descriptive statistics and represented in percentage form using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.0. Specific tests were used in analyzing the hypotheses of the study. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to analyze the first hypotheses which states that: female adolescents with internal locus of control are more likely to have a higher resistance to peer pressure their male counterparts, because the researcher was interested in determining the difference between two groups. The second hypotheses: male adolescents are more likely to have higher resistance to peer pressure scores as compared to female adolescents. This hypothesis was tested using an independent t-test because the researcher was interested in finding the difference between two independent groups with respect to scores on a resistance test. And finally, the third hypotheses which is that there is a positive relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure is analyzed using the Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient (Pearson r), because the researcher is interested in the relationship that exists between the two variables.

Ethical consideration

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The researcher executed the ethical procedures practiced by researchers in conducting research, which is approved by Regent University College of Science and Technology Ethical Research Committee,1 amongst them are the following:

Informed consent: With respect to the principle of informed consent, introductory letters were sent out to the school authorities to seek permission before conducting the survey. The topic, and purpose were clearly outlined in these letters to the school authorities as well as the participants. A copy of the questionnaire was also shown to the school authorities.

Assured confidentiality: The researcher assured the participants that their responses would not be disclosed to any third party and indeed it was not disclosed to any third party.

Anonymity: The participants of the study were assured that their identities would be concealed as there is no way to trace back responses to them. To achieve this there was no option for any form of identification by name or number on the questionnaires and participants were advice not to put down any.

Avoiding plagiarism: To avoid the issue of plagiarism in this study, all research works, and articles used in this study for reference or other reasons were acknowledged in reference.

Avoiding coercion: In administering the tool for data collection, all participants were informed that they were participating in the research at their own volition and could opt out at any point in time. The participants were made to understand that they were not obliged to participate in anyway. This Ethical research committee also agrees with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The present study sought to examine the following hypothesis:

a) Female adolescents with internal locus are more likely to have a higher resistance to peer pressure than their male counterparts.

b) Male adolescents are more likely to have higher resistance to peer pressure score than female adolescents.

c) There is a positive relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure.

The main goal of the study was to find out whether an individual’s locus of control, be it internal or external influences his or her resistance to peer pressure. Also, the main analysis apart from analyzing the influence locus of control has on resistance to peer pressure, analyzed the influence of age and gender between the variables. Below is a presentation of the results from the analysis of the data that was collected.

Demographic data

The sample was made up of 144 participants from two (2) senior high schools in Accra. In terms of gender, the participants consisted of 51.4% male and 48.6% female. Form Ones made up 38.2%, Form Twos 34.0% and Form Threes 27.8% of the participants. With regards to religion, findings show the following percentages for Christianity, Islam, Traditional and Other respectively: 81.9%, 14.6%, 2.1% and 1.4%. A two-way ANOVA was conducted that examined the effect of sex and locus of control on resistance to peer pressure. There was no statistically significant interaction between the effects of sex and locus of control on resistance to peer pressure, F (1, 140) = 0.100, p = .752. Hence, the hypothesis that “females with internal locus of control are more likely to have a higher resistance as compared to their male counterparts” was not supported.

Hypothesis 2: Males are more likely to have higher resistance to peer pressure scores as compared to females

This hypothesis was analyzed using an independent t-test because the researcher was comparing two independent groups (females and males).

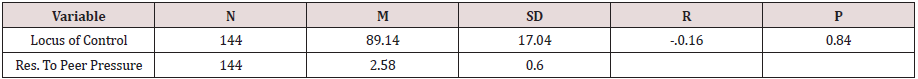

Hypothesis 3: There is a positive relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure

This hypothesis was analyzed with Pearson r Moment correlation in order to find the relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure.

Discussion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The main aim of this study was to determine the effect of locus of control on resistance to peer pressure amongst adolescents in 2 selected senior high schools in Accra. The results revealed that no significant interaction exists between sex, locus of control and resistance to peer pressure. This means that the relationship between a person’s sex and his or her locus of control does not influence his or her level of resistance to peer pressure. There are several factors that can attribute for non-significant data they include: the methodology, the type of questionnaire used, the cultural background of participants, as well as intellectual capacity or ability. However, results of sex and locus of control showed that out the participants, 77.1% have external locus of control whereas 22.9% have internal locus of control. The results also showed that the majority of females (N=56) have external locus of control than males (N=55) with external locus of control. The difference, just like the study by Cooper et al. (1981) is very small. There was also a small difference found in the number of females and males with internal locus of control, a total of males (N=19) scored higher on internal locus of control as compared to females (N= 14). The results from the second hypothesis showed a significant (p<.05) difference in sex with relation to resistance to peer pressure. Contrary to the stated hypothesis that “male adolescents are more likely to have a higher level of resistance than female adolescents”, results show that female adolescents rather scored higher in resistance to peer pressure. This result agrees with the findings of Steinberg & Silverberg who also found that females have a higher score in resistance to peer pressure as compared to males. The third hypothesis which expected a positive relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure also resulted in a statistically non-significant (p>.05) value but a negative correlation was obtained. This means that a person’s level of resistance cannot be used to predict his or her locus of control. It was expected that an individual with internal locus of control will score higher on the test for resistance to peer pressure according to the social learning theory [6].

Conclusion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

The present study investigated the effect of locus of control on resistance to peer pressure. 144 adolescents participated fully in the study. The study hypothesized that: Female adolescents with internal locus are more likely to have a higher resistance to peer pressure than their male counterparts. Male adolescents are more likely to have higher resistance to peer pressure score than female adolescents. There is a positive relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure. Locus of control was measured using a structured questionnaire developed by [7]. Higher scores are associated with external locus of control. Resistance to peer pressure was measured using a structured questionnaire developed by [21] with higher scores indicating higher resistance to peer pressure. The first hypothesis, second and third hypotheses were tested using the following analytical tests respectively: a 2-way ANOVA, an independent t-test, and a Pearson-r moment correlation. The relationship between sex and resistance to peer pressure was found to be statistically significant with females scoring higher on the resistance to peer pressure scale as compared to male adolescents, whereas the effects of sex and locus of control on resistance to peer pressure as well as the relationship between locus of control and resistance to peer pressure were statistically non- significant thus had no link whatsoever to each other as stated. To conclude, female adolescents generally scored lower on internal locus of control as compared to male adolescents.

Recommendations

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

This study provides support for continuing research regarding how locus of control affects resistance to peer pressure in the Ghanaian society.

References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Purpose of Study

- Objective of Study

- Delimitation of study

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Social Learning Theory

- Theory of Learned Helplessness

- Conceptual

- Review of Empirical Data

- Gender and Peer Pressure

- Methodology

- Ethical consideration

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- References

- Akhtar A, Shailbala S (2014) Gender differences in locus of control. Indian journal of Psychological Science.

- Baldo R, Harris M, Crandall J (1975) Relations among psychosocial development, locus of control and time orientation. J Genet Psychol 126(2d Half): 297-303.

- Beck AT, Steer RA (1988) Beck Hopelessness Scale: Manual. Psychological corporation.

- Berndt TJ (1979) Developmental change in conformity to peers and parents. Developmental psychology.

- Bingenheimer JB, Elizabeth A, Ahiadeke C (2015) Peer influences on sexual activity among adolescents in Ghana. Stud Fam Plann 46(1): 1-19.

- Boruah Aroonmalini (2016) Positive Impacts of Peer Pressure: A Systematic Review. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology.

- Brackney BE, Westman AS (1992) Relationships among hope, psychological development and locus of control. Psychol Rep 70(3 Pt 1): 864-6.

- Brown BB (1982) The Extent and Effects of Peer Pressure among high school students: A retrospective analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescents11: 121-133.

- Cohen S, Rothbart M, Phillips S (1976) Locus of control and the generality of learned helplessness in humans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychologypp: 1049-1056.

- Cooper HM, Burger JM, Good TL (1981) Gender differences in the academic locus of control beliefs of younger children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 40(3): 562-572.

- Corsini J (1999) The dictionary of psychology. Philadelphia, USA: Taylor & Francis Press, USA.

- Dunn DS (2001) Statistics and data analysis for the behavioural sciences. New York: McGraw-HillChildhood and Society, New York: Norton, New York.

- Hiroto D (1974) Locus of control and Learned helplessness. Journal of Experimantal Psychologypp: 187-193.

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE (2015) Monitoring the future: national survey results on adolescent drug use: 2014 Overview of key findings. Ann Harbor, Michigan: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, USA.

- Krosnick Judd (1982) Transitions in Social Influence at Adolescence: Who Induces Cigarette Smoking?Developmental Psychology 18(3): 359-368.

- Laursen B (2013) Speaking of Psychology : The good and bad of peer pressure.

- Levenson H (1972) Multidimensional locus of control in psychiatric patients. Journal of consulting and clinicalpsychology.

- Malhotra N, Peterson M (2006) Basic Marketing Research: A decision-making approach. New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall, USA.

- Manger T, Eikeland OJ (2000) On the relationship between locus of control, level of ability and gender. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 41(3): 225-229.

- McPherson A, Martin C (2017) Are there gender differences in locus of control to alcohol dependence.J Clin Nurs26(1-2): 258-26.

- Medley A, Kennedy C, O'Reilly K, Sweat M (2009) Effectiveness of Peer Education Interventions for HIV Prevention in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Educ Prev21(3): 181-206.

- Miller JF (1986) Development of an instrument to measure hope (Unpublished doctoral dissertation).University of Illinois, Chicago.

- Moore T (1957) Retrieved from Competence to Stand Trial: psychology.

- Nowicki S, Strickland B (1973) A Locus of Control Scale for Children. Journal of consulting and Clinical Psychologypp: 148-154.

- Oliner S, Oliner P (1988) The Altruistic Personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe. New York: Free Press, New York.

- Rotter JB (1966) General Expectancies for internal versus External control of reinforcement.Psychologica Monographspp: 556-609.

- Schmidt MR (2015) Moderating effect of negative peer group climate on the relation between men's locus of control and aggression toward intimate partners. Master's thesis, University of Tennesseep. 16-17.

- Seligman ME, Maier SF (1967) Failure to escape traumatic shock. Journal of experimental psychology.

- Spector P (1983) Locus of control and social influence susceptibility: Are externals normative or informational conformers? Journal of psychology 115(2): 199-201.

- Steinberg L, Monahan K (2007) Age Differences in Resistance to Peer Pressure. Dev Psychol 43(6): 1531-1543.

- Steinberg L, Silverberg SB (1986) The Vicissitudes of Autonomy in Early Adolescence. Child Dev 57(4): 841-851.

- Taylor ED, Wong CA (1996) Gender Differences in the Impact of Peer Influences adn Peer Orientation on African-American Adolescents' School Value and Academic Achievement. Society for Research on Adolescents. Boston, Massachusetts.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...