Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Introducing CAOS: The Cork Attitudes to Older Adults Scale Volume 7 - Issue 1

Mike Murphy*, Helen O Sullivan Curtin and Seán Hammond

- School of Applied Psychology, University College Cork, Ireland

Received:December 19,2022; Published:January 3, 2023

Corresponding author: Mike Murphy, School of Applied Psychology, University College Cork, Ireland

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2023.07.000251

Abstract

Ageist attitudes represent a threat to successful ageing. To understand the dimensions of ageism, identify predictors and correlates, and assess interventions, it is necessary to have a robust measure. Existing commonly-used measures are dated and open to criticism. This study sought to develop a contemporary scale in a bottom-up fashion. Focus groups and a literature search led to the development of an 80-item scale, named CAOS-V1. Data from 303 participants were subjected to Principal Components Analysis, leading to a 36-item, 4-factor version (CAOS-V2). This version was completed by 308 participants and a Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted, rendering a 34-item, 4-factor scale, named CAOS. Validity of the CAOS was shown through correlations with related measures; internal consistency of the CAOS and of each subscale was adequate. The three-week test-retest reliability was acceptable. This new measure of attitudes to older people is valid, reliable, and can prove of value in research.

Keywords: Ageism; attitudes; psychometric scale; measurement

Abbreviations: ASD: Aging Semantic Differential; r-ASD: Revised Version of the Aging Semantic Differential; CAOS: Cork Attitudes to Older Adults Scale; MIIC: Mean Inter-Item Correlation; PCA: Principal Components Analysis; FSA-Fraboni Scale of Ageism; AASAgeing Anxiety Scale; BFI-Big Five Inventory; SCBCS-Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale; GLTEQ-Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire

Introduction

We live in a time of extraordinary demographic change. Population projections from the United Nations [1] suggest that the proportion of the world population aged over 60 years will climb from 12.3% in 2015 to 21.5% in 2050; areas which have already experienced marked increases will see this process continue (e.g. Europe increasing from 24% to 34%, North America from 21% to 28%), but the greatest proportionate increases are predicted to be in Latin America & the Caribbean (from 11% to 26%) and Asia (from 12% to 25%). Examination of the data for individual countries shows a particularly sharp predicted increase in the numbers of people aged 80+ in the same period - for example from 5.7% to 14.4% in Germany, from 6.8% to 15.6% in Italy, from 5.9% to 14% In Spain - in addition to a marked increase in the 60-79 age group. In Ireland, it is projected that the 60-79 age group will grow from 18.4% to 31%, while the 80+ age group will grow from 2.9% to 8.5%. These are developments which are to be welcomed as the fruit of advances in healthcare and living standards; but they also have implications which must be addressed.

Perhaps the most important among the implications of an ageing population is the area of healthcare. As mentioned above, improvements in living conditions and in health sciences have played a large part in the increase in longevity; reported that the leading causes of death in 1900 were infectious diseases, while by 2010 this had changed to being largely chronic lifestyle-related conditions such as cancers and cardiovascular disease. Conditions which were previously fatal are now often curable, and other conditions which were once rapidly lethal can now be controlled and restricted in their impacts.

Therefore, we must anticipate larger numbers of people living with chronic medical conditions and requiring one degree or an other of ongoing health support. In addition to this, an ageing population will lead to increased numbers of people with progressive degenerative conditions. Prevalence and incidence of dementias, for example, increase at a higher rate with age [2,3] rates of osteoarthritis also increase with advancing age [4]. The increase in levels of conditions such as these will also prove important. And while these conditions will require access to health and related support, older people will of course also need to access services for other problems, such as depression, in the same way that younger people do.

Furthermore, as population ageing progresses, we will see ever greater numbers of people who are no longer as a matter of course integrated in the social structures in which younger people spend a great deal of their day - schools, colleges, workplaces. When we consider the evidence that social engagement is an important contributor to wellbeing [5], and that a sense of contributing to society and of ‘mattering’ is also a factor in wellbeing [6], it is evident that there will be an increased need to provide opportunities for social and occupational engagement for older adults. Negative attitudes to older people constitute an immediate and obvious threat to the provision of support, services and opportunities outlined above. Nelson [7] has outlined the difficulties faced in the healthcare domain, with insufficient numbers of medical students and junior doctors showing an interest in working with older people - often because this is seen as a depressing and hopeless occupation.

Kane [8] describes the negative experience older people report of engagements with medical professionals and health workers, with issues such as infantilization, paternalism, and pessimism being common. Other literature [9] shows psychiatrists approaching assessment and treatment of depression differently in different age groups, a tendency for older people to be treated with medication rather than psychotherapy [10] and trainee social workers tending to believe psychotherapy less appropriate for older people [8]. In relation to employment opportunities, a review by Dennis and Thomas [11] reported that equally qualified older people were likely to be considered less favourable by employers, and that older workers were viewed by employers as less adaptable and flexible [12-15].

All the above being the case, interventions to address ageist attitudes are vital if society is to provide a positive environment for older people. However, for such interventions to be assessed, and for the nature of the relationship between ageist sentiment and behaviour to be understood, it is necessary to have a valid and reliable tool. We contend that the most used tools at this time are found wanting. Among the most used tools to measure attitudes to older people are the Attitudes Toward Older Persons Scale [12] the Aging Semantic Differential (ASD) [16] and the Fraboni Scale of Ageism [14]. An immediate concern with these measures is that they are quite dated; this is not necessarily an issue, but just as expression of racist and sexist attitudes has changed with time, such that measures of these constructs from previous decades might not be appropriate today, we must consider the possibility that the same holds true for ageism. A second concern relates to the validity and reliability of these measures.

A study [17] among large sample of students in a US University examined both the Kogan-OP, and a revised version of the ASD (r-ASD) [18] and found both to be problematic. The Kogan-OP is designed to consist of a positive and a negative subscale, each of the same length with each item in the positive being matched with its antonym in the negative; however, this study found that the two subscales correlated at far less than might be expected (r=.51), and that some of the word pairs did not correlate significantly. The r-ASD, in its turn, was found to demonstrate problematic factor structure, with the proposed single factor solution of [16] not emerging convincingly, and with a four-factor model proving a better fit-although the four factors correlated at over 0.8.

The FSA is a very widely used measure of ageism, but it too has problems. One major issue with the FSA is that it was constructed in a top-down fashion, with the authors developing items to meet the three components of ageism identified by Butler [19]. Thus, the scale did not take into consideration the sense of its target population of what characterized ageism, but instead imposed both structure and content. In addition to this, some of the items of the FSA now seem to us to be dated and of questionable validity (for example “It is best that old people live where they won’t bother anyone”, and “Most old people should not be trusted to take care of infants”). A very recent addition to the literature on attitudes to older people is that of Cary, Chasteen and Remedios [20], whose Ambivalent Ageism Scale sought to address both benevolent and hostile attitudes. This scale, however, derives its items from re-working of pre-existing instruments and so does not necessarily represent the spectrum of contemporary attitudes.

The purpose of the research presented in this paper was to develop a modern scale, using a combination of top-down and bottom- up approaches, for the assessment of attitudes of young adults to older people. It consists of four separate studies: item generation; item reduction and exploratory factor analysis; confirmatory factor analysis and validation; and measurement of test-retest reliability. These studies are presented in turn.

Study 1: Item Generation

This section of the research involved two components - focus group research and a review of literature. The first step was the focus group work.

Participants

Twenty undergraduates, aged between 18 and 25y posters with equal numbers of males and females were recruited in an ad hoc fashion through placing poster on noticeboards across the University. These were randomly splits into two groups of 10, which participated in two separate focus groups. As the themes emerging from both groups were largely identical, it was felt that saturation had been reached and that further focus groups were not required.

Procedure

Each focus group was facilitated by one of the authors were (HO’SC); a semi-structured schedule which focused on typical characteristics of older people, their shared characteristics, their differences from younger people, common positives and negatives of older age was employed to elicit data. In accord with the recommendation of [21] the focus groups were not recorded but instead extensive notes were taken, and these notes were subjected to thematic analysis [22] to develop a list of themes.

Results

The analysis of the focus group data yielded 122 themes, and a review of literature in attitudes to aging added another seven themes, leading to a tally of 129. This list of themes was reduced, through the deletion of synonyms and antonyms identified by both HO’SC and MM, to a final list of 80. These 80 themes (Appendix 1) formed the basis for the first iteration of the survey, presented as Study 2.

Study 2: Item Reduction and Exploratory Factor Analysis

Participants

An email, with a link to an electronic survey, was sent to 2,500 randomly selected students at University College Cork. Complete responses were received from 303 participants (213 female) - a response rate of 12.1%. The age range of respondents was from 18 to 72, with a mean age of 26.1.

Instruments

The first version of the Cork Attitudes to Older Adults Scale (CAOS-V1) consisted of list of the 80 themes presented in Appendix 1, with the instructions “To what extent, on a scale of 1 to 5, do you agree that the following words or phrases describe older adults?” The response options were explicitly labeled as: strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree.

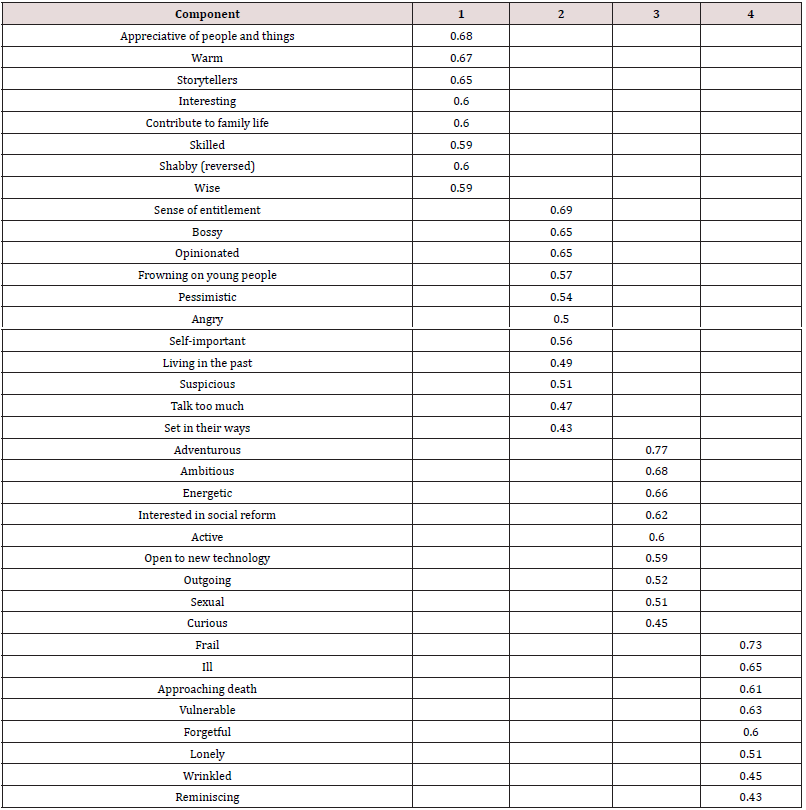

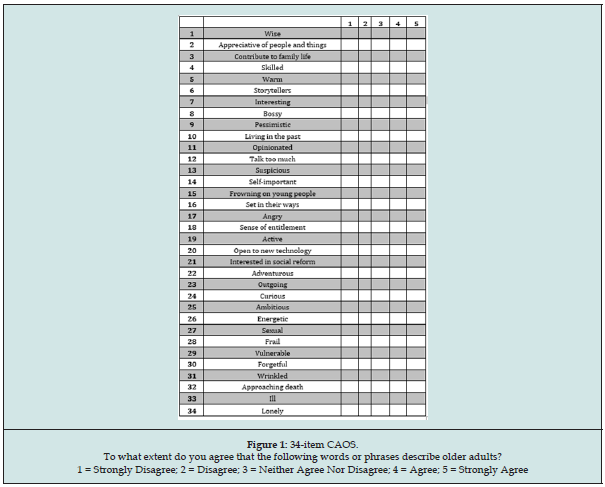

Figure 1: 34-item CAOS. To what extent do you agree that the following words or phrases describe older adults? 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neither Agree Nor Disagree; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree

80 items of the CAOS-V1 were subjected to Principal Components Analysis (PCA). The KMO measure of sampling adequacy (.86) indicated that the sample size was acceptable, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 [3160] = 10873.77, p<.001) was significant, indicating that the data were appropriate for PCA [23] (Figure 1). Considering the eigenvalues, the scree plot, and the results of a parallel analysis, it was felt that a four-factor solution best fit the data.

When a second PCA was conducted, with a four-factor model being specified, Direct Oblimin rotation was applied; it was found that there was significant correlation between several of the four factors which emerged, and therefore this oblique rotation was appropriate. It was now possible to engage in item reduction. Items which were not loading strongly on any factor, and those which cross-loaded on more than one factor were identified and removed from the item pool; items dropped at this time included, inter alia, ‘happy’, religious’, ‘frugal’ and ‘confident’. Furthermore, those items which displayed limited variance in response distribution were dropped [24] this step led to the removal from the item pool of a small number of items, including ‘caring’ and ‘affluent’. Once these items had been removed, the inter-item correlations of each of the four factors were examined; Clark and Watson recommend keeping only those items which fall within the .15-.5 range; on this basis several more items were dropped, including ‘productive’, ‘fearful’, ‘loving’ and ‘cranky’.

Finally, on examination of the remaining items, and in accordance with Clark and Watson’s recommendations, a small number of items were removed as both MM and HO’SC agreed they did not fit coherently with the factors onto which they loaded. Following the item reduction, 36 items remained. When PCA was conducted on these items, a four-factor structure explaining 44.48% of the variance emerged, with the amount of variance explained by individual factors ranging from 9.77% to 12.18%. Application of Direct Oblimin rotation showed that there were significant correlations between some of the factors (Table 1) and so this rotation was maintained.

The rotated component matrix is presented in Table 2. The four subscales were named ‘Positive’, ‘Negative’, ‘Engagement’ and ‘Decline’, with 8, 11, 9 and 8 items respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale was acceptable -.81, .83, .82 and .78 respectively. For scales with fewer than 10 items, the mean inter-item correlation (MIIC) is considered a more appropriate measure of internal consistency [25], with a score of .3 or higher considered adequate [26] MIIC scores for factors 1, 3 and 4 were .35, .33 and .31 respectively. When total scores for the ‘Negative’ and ‘Decline’ subscales were reversed, it was possible to compute a total score by adding the subscales together. In this case, higher scores indicated a more positive attitude to older adults, and Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Study 3: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Validation

The purposes of this study were twofold:

a) To perform a confirmatory factor analysis on the CAOS, to assess the structural validity of the four-factor model identified in Study 2.

b) To establish the validity of the scale, through assessing construct validity (employing correlations with related measures, such as an ageism scale, aging anxiety scale, compassion, contact with older adults, and agreeableness) and discriminant validity (through correlations with unrelated variables, such as exercise level). It was anticipated that there would be strong correlations with ageism scores. It was also expected that there would be a quite strong correlation with aging anxiety, as ageism can be understood as an ego-protective mechanism which protects one against the threat of one’s own ageing [27]; ageing anxiety has previous been found to have a moderate-to-large correlation with ageism [28]. Compassion (Boswell) and agreeableness [29] have both been found to be related to lower levels of negative or prejudicial attitudes with moderate effect sizes. Intergenerational contact [30] has also been found to reduce age-related stereotyping.

Participants

An electronic survey instrument was sent to 5,000 randomly selected students at University College Cork, none of whom had participated in study 2. A total of 308 participants (219 female) completed the survey - a response rate of 6.16%. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 62, with a mean age of 24.3.

Instruments

The second version of the Cork Attitudes to Older Adults Scale (CAOS-V2), a 36-item, 4-factor scale emerging from Study 2, was presented to all participants in this study. Its psychometric properties are presented in the results section below. The FSA [14] was also administered. This 29-item scale is an established measure of ageist attitudes, with higher scores indicating more negative attitudes. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.9. The Ageing Anxiety Scale (AAS) [31] is a measure of the extent to which respondents feel anxiety about the ageing process. This is a 20-item scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of ageing anxiety. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was .85. Compassion was assessed through the administration of the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale (SCBCS) [32] a five-item scale in which higher scores indicate higher levels of compassion. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .9. Agreeableness was measured using the relevant subscale of the Big Five Inventory [33]. The agreeableness subscale has 9 items, each scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater agreeableness. Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was .78.

Contact with older adults was assessed using a single item derived from Boswell [28], with levels of contact scored on a 7-point Likert scale. Exercise level was measured using the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire [13] which includes questions on the frequency with which respondents engage in mild, moderate, and strenuous exercise in a typical week, and generates a total exercise score.

Analysis & Results

The initial analysis in this phase of the research involved performing a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the 36-item, 4-factor model which emerged from Study 2. The results showed that the four subscales identified in Study 2 emerged as clearly distinguished constructs. Two items failed to load on any subscale at the required level of 4 and did not appear to clearly belong to any of the subscales, and so were removed from the model [24,35]. The remaining 34-item scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .88, and the four-factor model explained 43.33% of the total variance. Component structure and item loadings are presented in Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha for each of the four subscales - positive, negative, engagement and decline-were .81, .82, .79 and .77 respectively. Mean inter-item correlations for each of the three shorter subscales - positive, engagement and decline - were .38, .3 and .32 respectively.

The structure was then evaluated using a model fitting procedure based on 10,000 replications of simulated data. The overall pattern of goodness of fit index for the four-factor model was .93, which signifies a reasonable fit [23]. The construct validity of the CAOS was assessed through its relationships with several other scales. A large correlation (r = -.63, p=.001) was found with scores on the FSA, moderate correlations were found with scores on ageing anxiety (r = -.4, p=.001) and agreeableness (r = .35, p = .001), and small-to-moderate correlations were found with both compassion (r = .25, p=.001) and contact with older adults (r = -.23, p=.001). As expected, no significant relationship was found with scores on the GLTEQ (r = .06, p=.26). A full correlation matrix is presented in Table 4. FSA-Fraboni Scale of Ageism; AAS-Ageing Anxiety Scale; BFI-Big Five Inventory; SCBCS-Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale; GLTEQ-Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire.

* p<.0005; ** p<.005; *** p<.05

Study 4: Measurement of test-retest reliability

Participants

The sample for this study consisted of 31 first-year psychology students, of whom 24 were female and 7 were male. The mean age was 22.55 years (sd = 10.27).

Procedure

The participants completed the 34-item CAOS, which emerged from Study 3, on two occasions, which were three weeks apart.

Analysis and Results

Total scores for the individual subscales and for the total scale were calculated for both T1 and T2. Scores at the two time-points were then correlated with one another. The three-week test-retest reliability for the full CAOS was .79. For the positive subscale it was .78, for the negative subscale .83, for the engagement subscale .72, and for the decline subscale .65.

Discussion

The purpose of this research project was to develop a new psychometric scale to measure attitudes to older people, and to do so in a bottom-up and data-driven fashion, to fashion a tool which reliably measures these attitudes in contemporary society. Focus groups, literature review, item reduction, exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis yielded a 34-item scale with four robust factors - positive, negative, engagement and decline - and which can also yield a total score through the reversal of the second and fourth subscales and a summing of the subscales.

The CAOS was validated through correlation with measures of related constructs, and with one measure of an unrelated construct. As expected, a large negative correlation was found with the FSA and a moderate negative correlation with ageing anxiety. Furthermore, and as expected, somewhat smaller positive correlations were found with agreeableness and compassion. We had, based on previous research [30], anticipated a positive relationship between attitudes to and prior contact with older people; in fact, we found the reverse, and we speculate that this may be related to the likelihood that many of our participants encounter older people largely through their studies and related work - therefore meeting older people largely in contexts where they are dependent and/or unwell. Internal consistencies for the full scale, and for each of the subscales, were strong.

The three-week test-retest reliability was strong for the full scale, and for each of subscales 1-3, but that for subscale 4 fell a little short of the desired level. The strengths of this research include the fact that the resulting scale has emerged in a bottom-up fashion, includes items which show variance across samples and are derived from attitudes expressed in recent focus groups, and has a robust factor structure. Another strength is that it has been developed in a university setting, conferring a clear validity in terms of measuring attitudes to older people among those who may have the option of working with older adults in subsequent careers.

A weakness of the work is that it has generated a scale entirely in the context of a single University. Future work we recommend includes assessing the validity of the scale in different populations - both among university students elsewhere and among different age groups and occupational groups. Research assessing the extent to which scores on the different subscales predict future career intentions could also prove useful, as results may point to specific interventions to improve uptake of training and work in these areas. As we see population ageing advance, and with this phenomenon likely to have implications for health and social care services internationally, we believe this new measure may be of considerable utility in many parts of the world. In conclusion, the research presented in this paper has yielded a multidimensional scale of attitudes to older people, which we feel has potential to be of benefit in terms of both research and teaching practice.

References

- (2015) United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: Key Findings & Advance Tables. New York, United Nations.

- Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S (1998) The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry 55(9): 809-815.

- Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L, Andersen K, Di Carlo A, et al. (2000) Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology 54(11): s4-s9.

- Zhang Y, Jordan JM (2010) Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 26(3): 355-369.

- Schwarzbach M, Luppa M, Forstmeier S, König HH, Riedel Heller SG (2014) Social relations and depression in late life- A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 29(1): 1-21.

- Piliaven JA, Siegl E (2007) Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin longitudinal study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48(4): 450-464.

- Nelson TD (2016) Promote healthy aging by confronting ageism. American Psychologist 71(4): 276-282.

- Kane MN (2004) Ageism and intervention: What social work students believe about treating people differently because of age. Educational Gerontology 30(9): 767-784.

- Bouman WP, Arcelus (2001) Are psychiatrists guilty of ‘ageism’ when it comes to taking a sexual history? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16(1): 27-31.

- Nelson TD (2005) Ageism: Prejudice against our feared future self. Journal of Social Issues 61: 207-221.

- Dennis H, Thomas K (2007) Ageism in the workplace. Generations 31(1): 84-89.

- Kogan N (1961) Attitudes toward older people: The development of a scale and an examination of correlates. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 62(1): 44-54.

- Rosencranz HA, McNevin TE (1969) A factor analysis of attitudes toward the aged. Gerontologist 9(1): 55-59.

- Fraboni M, Saltstone R, Hughes S (1990) The Fraboni Scale of Ageism (FSA): An attempt at a more precise measure of ageism. Canadian Journal of Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement 9(1): 56-66.

- Jones DS, Podolsky SH, Greene JA (2012) The burden of disease and the changing task of medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 366(25): 2333-2338.

- Polizzi K (2003) Assessing attitudes toward the elderly: Polizzi’s refined version of the Aging Semantic Differential. Educational Gerontology 29(1): 197-216.

- Iwasaki M, Jones JA (2008) Attitudes toward older adults: a re-examination of two major scales. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education 29(2): 139-157.

- Polizzi KG, Millikin RJ (2002) Attitudes toward the elderly: Identifying problematic use of ageist and overextended terminology in research instructions. Educational Gerontology 28(5): 367-377.

- Butler RN (1978) Thoughts on aging. American Journal of Psychiatry 135(1): 14-16.

- Cary LA, Chasteen AL, Remedios JR (2017) Ambivalent Ageism Scale: Developing and validating a scale to measure benevolent and hostile ageism. The Gerontologist 57(2): e27-e36.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA (2014) Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (5th). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101.

- Tabachnick BG & Fidell LS (2012) Using Multivariate Statistics (6th). Boston, MA-Pearson Education, UK.

- Clark LA, Watson D (1995) Constructing validity: Basic issues in scale development. Psychological Assessment 7(3):309-319.

- Mitchell M, Jolley J (2012) Research Design Explained (8th) Belmont, CA-Wadsworth, USA.

- Briggs SR, Cheek JM (1986) The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality 54(1): 108-148.

- Snyder M, Miene PK (1994) Stereotyping of the elderly: A functional approach. British Journal of Social Psychology 33: 63-82.

- Boswell SS (2012) Predicting trainee ageism using knowledge, anxiety, compassion, and contact with older adults. Educational Gerontology 38(1): 733-741.

- Bergh R, Akrami N (2016) Are non-agreeable individuals prejudiced? Comparing different conceptualizations of agreeableness. Personality and Individual Differences 101: 153-159.

- Alcock CL, Camic PM, Barker C, Haridi C, Raven R (2011) Intergenerational practice in the community: A focused ethnographic evaluation. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 21(1): 419-432.

- Lasher KP, Faulkender PJ (1993) Measurement of aging anxiety: Development of the Anxiety About Ageing Scale. International Journal of Ageing and Human Development 37(4): 247-259.

- Hwang JY, Plante T, Lackey K (2008) The development of the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale: An abbreviation of Sprecher and Fehr’s Compassionate Love Scale. Pastoral Psychology 56(4): 421-428.

- John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle R (1991) The Big Five Inventory: Versions 4a and 54. Technical Report: Institute of Personality and Social Research, Berkeley University of California.

- Godin G, Shephard RJ (1985) A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Canadian Journal of Applied Sports Science 10(3): 141-146.

- Hinkin TR (1995) A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management 21(5): 967-988.

Appendix 1

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...