Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

In terms of melodies, do we prefer what we already know? Volume 8 - Issue 5

Lucie Pageat*, Manon Chasles, Estelle Descout, Alessandro Cozzi and Patrick Pageat

- IRSEA Institute, France

Received: May 23, 2025; Published: June 03, 2025

Corresponding author: Lucie Pageat, IRSEA Institute, 216, D201 – 84400 APT, France.

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2025.08.000298

Abstract

Preferences for music are due to different music features like tempo, mode or arousal. It can also come from internal criteria like music that has been played during childhood or the aesthetic pleasure. Repeating the music can also lead to preference for this music. The aim of this study was to see if childhood musical experiences affect adulthood preferences. Seventy-five adults passed the test in which we used the lullaby “Brother John” and created three audios that has the same music features as it. We made four groups that listened to four sequences containing the four audios in different presentation orders. Results showed a higher percentage of « Brother John» choice in the first listening. This choice decreased after. This study helps to better understand how musical experiences during childhood could affect adulthood preferences and open a way of investigation into the impact of musical experiences during critical attachment phases.

Keywords: Music, preferences, lullabies, memory, childhood

Introduction to Force-based Nightmare

Preference is a complex made of motivationally salient properties that can fluctuate in time and be related to many things [1]. In music, many studies tried to find the origin of preferences [2- 4]. People tend to listen to music that can modulate their mood [5]. They found that many features in music can influence the arousal of the listener like the tempo, the mode and the percussiveness. Minor mode, increase of percussiveness and increase of tempo lead to the increase of arousal and modulate emotions [6]. Emotional valence of music has also been shown to influence the liking of music. Positive and arousal music is more liked than negative and less arousal music [7]. Infants’ music preferences are influenced by previous exposure and by the nature of music [8]. The aesthetic pleasure also modulates liking towards music. Not only do the tempo, mode or arousal character of the music play a role in the liking, but these features can be associated with a personal perception of aesthetics. This perception correlates with the activation of reward functions in the brain meaning that more than the music features, it is the perception of them that increases or decreases our liking and preference for a music [9].

Regardless of music features that can modulate the preference or the liking for it, there are some ways to create a preference for some music. In fact, repeated exposure can increase the affective response to music even for listeners who are not used to listening to this type of music [10]. Cognitive functions and familiarity are also a cause of the preference in music [11]. The personality characteristics also help us to understand music preferences and to predict changes in music preferences [12]. Memory also plays a role in preference in music. Music played during childhood leads to lifelong preferences towards theses music. Home environment plays a role in adulthood preferences in music [13].

Primacy and recency bias have been shown to modulate preferences in many features like taste [14], memory [15], communication [16], on clicking behaviour [17] or on olfaction [18]. No research was found to prove the existence of primacy and recency bias on preferences towards music. The early build of preferences towards music seems hard to explain. Where a lot of research explains which, musical character is more likeable than another, or which music creates more emotions or arousal, it does not explain clearly what is causing the preference. It seems like this preference is created in the early ages of infancy but may change during childhood or adolescence. If preference is built considering the arousal level of the music, the musical features, a positive mood and is strongly related to music that we listened to during infancy, it may be correlated with lullabies. These nursery rhymes are one of the first pieces of music heard of children. Parents and particularly mothers usually sing lullabies to children to soothe, and schools display these types of sounds. In this study, we want to investigate if during adulthood, we still prefer sounds that we heard during infancy compared to unknown rhymes that have the same musical features as a well and internationally known rhyme “Brother John”. We also want to see if primacy and recency influence our preference towards music.

Method

Participants

This study has been a two-part essay. One part of the participants did the test onsite, and the other part did the test online. The participants who completed the questionnaire onsite were recruited at the IRSEA Institute by email sent to all the employees. The online participants were recruited by an announce posted by the IRSEA Group account on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. All the data have been anonymized. A total of seventyfive people participated in this study. Forty-four people completed the questionnaire in the IRSEA Institute and thirty-one people completed the online version. Participants were divided into four groups with four different listening orders of the tracks containing the four audios. Counterbalancing of music and tracks is performed to compensate for biases of primacy and recency. The groups were not balanced in terms of sex or age, but participants were randomly assigned to a group and people with hearing or visual impairments were not included in the study. The participants needed to be adults, so we recruited people aged between 20 and 70 years old (Institute Servier, 2010). Participants were from many different nationalities like Italian, Indian, Pakistanis, Turkish, French or Spanish.

Material

Four musical audios were used in this experiment. The first was the simplified chorus of the lullaby “Brother John” with only the right-hand notes of the piano part. As a comparison three other audios reduce as many biases as possible, particularly with regard to individual musical preferences, and having decided to create the audios ourselves, we carried out a more detailed study of the “Brother John” nursery rhyme, using notions of solfeggio. After research and analysis, we concluded that “Brother John” is in major, in the key of G, and that the melody contains a total of 32 notes. Also, the measure is in 2/4, i.e., there are 2 beats per measure, and the pulse is a quarter note. There are 16 bars in the rhyme, it is in the key of F and the key signature contains a B flat. According to this information we decided to keep the original tempo of 120 BPM. The rhyme thus contains 20 quarter notes, 4 half notes, 2 sixteenth notes, and 2 dotted sixteenth notes (Annex – 1.1/1.2). The only things that we changed were the notes and the order of the rhythms.

Each participant who did the onsite version was given a document containing the instructions for the experiment and the order in which it will be listened to. Depending on the group, the audios were not the same for purposes of changing the order of listening and to still giving the same participant sheet to everyone. For the people who did the online version, we gave a link in the recruitment post that led to a form where people had to give their email address. Then, we send the questionnaire individually changing the group each time. We then equilibrated depending on how many answers we got. To build the online questionnaire, we created 16 tracks with the four audios and created 16 YouTube videos with these tracks. We put the same questions in the form as the questions we asked during the live sessions. An example of track is provided in the supplementary material.

Procedure

Depending on whether the participant did the test live or online, there were different procedures. In the case of the live test, after they have registered on the sheets or directly to the study monitor, the participants came to a room with desks and chairs and were assigned a chair, each participant received a handover sheet and a pen. The study monitors displayed the instructions which are: “You are going to listen to four sequences of audio tracks. Each sequence is composed of four tracks. An example of sequence will be provided in the online supplementary online material. After each sequence of four tracks, you are going to circle the one that you preferred. You will do that for the four sequences. There will be a break of 15 seconds between each sequence during which you can circle your answer and rest. Your data is going to be anonymized, and you can stop this trial at any time. Do you agree to participate in this trial? Do you have any questions?”. If each participant gave their agreement, the study monitors displayed the audio tracks in the order corresponding to the group that they were in. To simplify the test for the study monitor, we did a list of the orders the audios were displayed for each group since in the software, audio 1 was always “Brother John” and audios 2,3,4 were the audios we created. The order of the different audios was:

Group 1: 1-2-3-4/2-4-1-3/4-3-2-1/3-1-4-2

Group 2: 2-4-1-3/4-3-2-1/3-4-2-1/1-2-3-4

Group 3: 4-3-2-1/3-1-4-2/1-2-3-4/2-4-1-3

Group 4: 3-1-4-2/1-2-3-4/2-4-1-3/4-3-2-1

After the participant finished the last hearing of the trial, the study monitors asked if the participant recognized one or more audio tracks, if they knew they had to give the name of the rhyme (beforehand, the study monitor had the translation of “Brother John” in different languages). If they didn’t recognize anything, the study monitors asked if the participant knew “Brother John”, if not, the participant was excluded from the study. For the participants doing the online version of the test, they first registered on a form by giving their email address. They were then assigned to a group, the first person giving his or her email address was in group 1one, the second one was in group 2. The same procedure was applied to the following applicants to make sure that the four groups were randomized and equilibrated in terms of number of participants. They had to complete the online questionnaire which involved listening to the four audio tracks presented as YouTube videos and then checking the case corresponding to the audio that they preferred. They were then asked if they recognized any audio and to name this audio. If the participant crossed “no” to the question about knowing the audio, its answers were excluded from the analysis. We also excluded people who took less than the time needed to listen to all the audios, but participants could take the time they wanted to complete the test.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using R version 4.1.2 (2021- 11-01). The significance threshold was fixed at 5%. The sample size was calculated using data from a similar published article to this study [19] to determine the minimum number of subjects needed to detect a significant difference. Calculations were based on a power of 80% and an alpha set at 5%, using the pwr package in R software. The results revealed that a sample of at least 156 observations would be required to detect a significant effect. Finally, 75 participants were included, with 4 repetitions for a total of 300 observations. This larger sample size was chosen to enhance statistical power and account for potential dropouts. Before carrying out these statistical analyses, a preliminary analysis was realized in order to assess the effect of data collection method (IRSEA or mail) on the choice of the rhythm, primacy and recency biases. The aim of this first step was to measure if that there was no significant difference between these two methods. For that, a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GzLMM), with the Binomial distribution, was used to analyse response variables. Effect of the data collection method was included in the model as a fixed effect. Subject was considered as a random effect. If there was a significant difference between the two data collection methods, this factor was considered in the future statistical analyses as a random effect.

The main analysis was to study the choice of rhythm (known (Brother John) or unknown) of each subject, during four listening sequences. This binary variable was analysed thanks to a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GzLMM) with the Binomial distribution. First, effects of group (1,2,3,4) and sequence (1,2,3,4) were included in the model as fixed effects in order to check that there was no significant difference and thus avoid a potential bias linked to the main question. Subject was included as a random effect. The final model was a NULL model, with no fixed effect, to answer the main problem of the study. After carrying out the main analysis, a sequence-by-sequence analysis was performed thanks to Chi-square tests to analyze the choice of rhythm for each sequence. A secondary analysis was performed to assess primacy and recency biases (for each of them, No: 0 or Yes: 1). A Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GzLMM) was used, with the Binomial distribution, to study these binary variables. First, effects of group (1,2,3,4) and sequence (1,2,3,4) were included in the model as fixed effects in order to check that there was no significant difference and thus avoid a potential bias linked to the question. Subject was considered as a random effect. The final model was a NULL model, with no fixed effect, to answer the second problem of the study. For all these analyses, multiple comparisons were performed thanks to the Tukey test, for significant effects.

Result

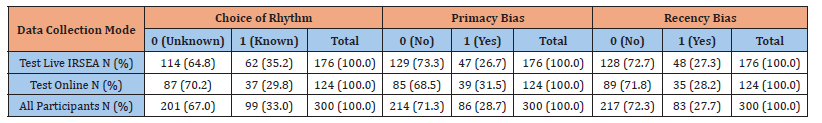

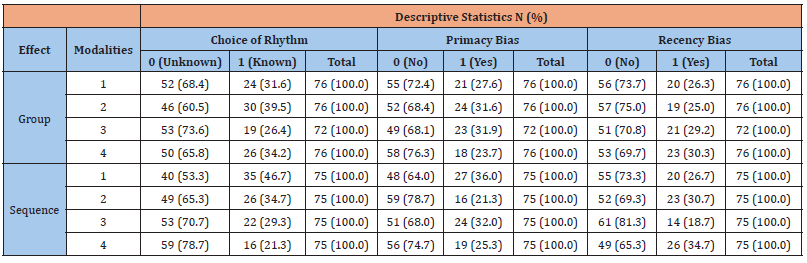

Firstly, we assessed if the method of data collection (online or live) could have an impact on the choice of rhythm, primacy and recency bias. Data about the method of data collection are available in Table 1. No significant difference was observed between data collection methods for those three parameters: choice of rhythm (GzLMM; DF=1; Chisq=0.0036; p-value=0.9520), primacy (GzLMM; DF=1; Chisq=1.7425; p-value=0.1868) and recency (GzLMM; DF=1; Chisq=0.0346; p-value=0.8525) biases. Hence, this factor was not included in future statistical analyses. For the main parameter “the choice of rhythm”, we observed no significant difference (GzLMM; DF=1; Chisq=1.9942; p-value=0.1579; Table 2). The sequence factor was included in the model as a random effect because of its significance (GzLMM; DF=3; Chisq=52.2590, p-value<0.0001). Indeed, as stated in Figure 1, the analysis showed a significant difference between sequences 1 and 2 (p-value=0.0003), 1 and 3 (p-value <0.0001), 1 and 4 (p-value <0.0001), 2 and 4 (p-value=0.0003) and 3 and 4 (p-value=0.0398). The group factor was not significant (GzLMM; DF=3; Chisq=2.8759; p-value=0.4112).

Figure 1: Percentage of known rhythms among rhythms chosen per sequence. Note: Participants of each group listened to four sequences of four audios that contained one known rhythm (Brother John) and three unknown created rhythms. This graphic shows the percentage of known rhythm that has been chosen in all groups during each sequence. Stars indicate significant differences according to a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (binomial distribution), followed by multiple comparisons performed thanks to the Tukey test. ***: p<0.001 **: p<0.01 *: p<0.05

After carrying out the main analysis, the sequence-by-sequence analysis (Figure 2) led to the conclusion that there was a significant difference between modalities 0 (Unknown rhythm) and 1 (Known rhythm) during sequence 1 (Chi-square test, DF=1; Chisq=18.7780; p-value<0.0001) and a trend is observed for the sequence 2 (Chisquare test; DF=1; Chisq=3.7378; p-value=0.0532). No significant difference was observed for sequence 3 (Chi-square test; DF=1; Chisq=0.7511, p-value=0.3861) and sequence 4 (Chi-square test; DF=1; Chisq=0.5378, p-value=0.4634). The analysis of the primacy bias (Table 2) showed no significant difference for the group effect (GzLMM; DF = 3; Chisq = 3.9120; p-value = 0.2711) but there was a significant difference between the sequences (GzLMM; DF = 3; Chisq = 12.0811; p-value = 0.0071). This factor was included in the model as a random effect because of its significance. The main analysis showed no significant difference regarding the primacy bias (GzLMM; DF = 1; Chisq = 0.9875; p-value = 0.3203).

Figure 2: Difference between expected and observed values of choice of rhythm per sequence. Note: Participants of each group listened to four sequences of four audios that contained one known rhythm (Brother John) and three unknown created rhythms. This graphic shows the difference between expected and observed values considering one-quarter of known rhythms and three-quarters of unknown rhythms. Stars indicate significant differences according to Chi- Square Tests. ***: p<0.001 **: p<0.01 *: p<0.05 t: 0.05≤p<0.10 NS: Not Significant

The analysis of the recency bias (Table 2) showed no significant difference for the group effect (GzLMM; DF = 3; Chisq = 1.1077; p-value = 0.7752) but there was a significant difference between the sequences (GzLMM; DF = 3; Chisq = 14.2158; p-value = 0.0026). This factor was included in the model as a random effect because of its significance. The main analysis showed no significant difference regarding the recency bias (GzLMM; DF = 1; Chisq = 0.0054; p-value = 0.9412)

Discussion

Results have showed that people tended to choose more the nursery rhyme “Brother John” than the three created audios on the first listening. However, the more sequences they were listening the less they would choose “Brother John” and go to one of the other audios. There was no significant difference of preference between the three other audios. The sequence effect is significant on primacy bias parameter and has been showed between sequence 1 and sequence 2, however, since “Brother John” was mostly chosen, it may affect the significance of this results. We also observed a significant sequence effect on recency bias parameter between sequence 2 and 3 and between sequence 3 and 4. Since these biases can be seen in the choice of preference for other senses like taste [20], taste and hearing [19] or the olfaction [21], it may be logical that we observe theses bias. No recency or primacy bias influences our preferences in terms of hearing towards nursery rhymes for the first listening but may influence our choice, mostly recency bias, after multiple listening of unknown songs.

We saw that the collect mode had no significant influence on the choice of preferred rhyme. That means that no matter how we conduct this trial, intrinsic motivations that influence the choice remain the same. The choice of the rhyme “Brother John” was based on the assumption that this nursery rhyme was known by many people and moreover, many nationalities. The testimonies we had confirmed this hypothesis because during the trial phase in the IRSEA Institute, many nationalities among which Italian, Spanish, Indian, Turkish, Pakistan and French were present, and everyone recognized it. Given that in many countries school is mandatory, and lullabies are displayed in nurseries and schools, we can conclude that most kids are exposed to the rhyme “Brother John” or to others lullabies that could have been chosen in the case of this trial. However, it could have been interesting to study if gender, age, and nationality had a significant effect on this trial to have statistics and not only testimonies and experience from the study monitor. Also, changes in the construction of the music can affect our mood or liking. Tonalities change for example can modify our mood and change the way we remember things [22]. The tempo, the mode or the percussiveness can affect our emotional state [23]. This is why it was so important to not modify any of these criteria in the construction of the three unknown sounds. They keep the same features as “Brother John”, but the musical notes and the rhythm are not in the same places. As seen in the results we can say that the construction of the audios was fair enough to “Brother John” to not cause any liking bias based on the tempo, rhythm or any other criteria but was also different enough to permit a great discrimination.

This study confirmed that in terms of hearing, we prefer what we already know. We can also confirm that the use of the rhyme “Brother John” is useful for many nationalities, ages, and genders. Recency bias can influence the choice of preference in case of multiple hearing of known and unknown songs. The choice of a nursery rhyme was motivated but the fact that many adults still remembered this sound many years after where they forgot many of them is surprising. In childhood, music plays a big role in literacy acquisition [24], working memory acquisition [25] and plays a role in communication and relatedness [26]. Nursery rhymes have been shown to help develop a lot of social, cognitive, communication, well-being and emotional maturity skills [27]. Since lullabies are involved in mother-infant bonding [28] and since we tend to remember more emotionally salient childhood experiences [29], we may prefer things that are related to a positive childhood experience.

Since singing lullabies to newborns helps the bonding, in the case of attachment ruptures or problems, it could be useful to encourage mothers or social workers to sing lullabies to newborns or kids. In children with developmental problems or even social skills deficiencies, lullabies could be an interesting tool used in association. It could also be interesting to study if our preferences in terms of music styles are related to different types of lullabies we were displayed during childhood. In terms of marketing, it could be interesting to take this study into account. As a criterion for memory, it could be interesting to test how childhood experiences on senses have an impact on adulthood in terms of preferences. Further studies should be conducted to properly evaluate the link between attachment with parents, attachment style and listening to nursery rhymes.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the participants for their time.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Dietrich F, List C (2013) Where do preferences come from? International Journal of Game Theory, 42(3): 613-637.

- Deihl ER, Schneider MJ, Petress K (1983) Dimensions of music preference: A factor analytic study. Popular Music and Society, 9(3): 41-49.

- Lamont A, Crich J (2022) Where do our music preferences come from? Family influences on music across childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Popular Music Education, 6(1): 25-43.

- MacLeod RB, McKoy CL (2012) An Exploration of the Relationships between Cultural Background and Music Preferences in a Diverse Orchestra Classroom. String Research Journal, 3(1): 21-40.

- Vuoskoski JK, Eerola T (2011) The role of mood and personality in the perception of emotions represented by music. Cortex, 47(9): 1099-1106.

- Van der Zwaag MD, Westerink JHDM, van den Broek EL (2011a) Emotional and psychophysiological responses to tempo, mode, and percussiveness. Musicae Scientiae, 15(2): 250-269.

- Witvliet CVO, Vrana SR (2007) Play it again Sam: Repeated exposure to emotionally evocative music polarises liking and smiling responses, and influences other affective reports, facial EMG, and heart rate. Cognition and Emotion, 21(1): 3-25.

- Volkova A, Trehub SE, Glenn Schellenberg E (2006) REPORT Infants’ memory for musical performances. Developmental Science, 9(6): 583-589.

- Suzuki M, Okamura N, Kawachi Y, Tashiro M, Arao H, et al. (2008) Discrete cortical regions associated with the musical beauty of major and minor chords. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience, 8(2): 126-131.

- Johnston RR, Childers GM (2022) Musical pantophagy: Is there an effect on changes in preference resulting from repeated exposure? Psychology of Music, 50(1): 141-158.

- Schäfer T, Sedlmeier P (2010) What makes us like music? Determinants of music preference. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(4): 223-234.

- Delsing MJMH, ter Bogt TFM, Engels RCME, Meeus WHJ (2008) Adolescents’ music preferences and personality characteristics. European Journal of Personality, 22(2): 109-130.

- Krumhansl CL, Zupnick JA (2013) Cascading Reminiscence Bumps in Popular Music. Psychological Science, 24(10): 2057-2068.

- Mantonakis A, Rodero P, Lesschaeve I, Hastie R (2009a) Order in Choice. Psychological Science, 20(11): 1309-1312.

- Morrison AB, Conway ARA, Chein JM (2014) Primacy and recency effects as indices of the focus of attention. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8: 6.

- McCann CD, Higgins ET, Fondacaro RA (1991) Primacy and Recency in Communication and Self-Persuasion: How Successive Audiences and Multiple Encodings Influence Subsequent Evaluative Judgments. Social Cognition, 9(1): 47-66.

- Murphy J, Hofacker C, Mizerski R (2006) Primacy and Recency Effects on Clicking Behavior. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2): 522-535.

- Annett JM, Lorimer AW (1995) Primacy and Recency in Recognition of Odours and Recall of Odour Names. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 81(3): 787-794.

- Ziv N (2018) Musical flavor: the effect of background music and presentation order on taste. European Journal of Marketing, 52(7/8): 1485-1504.

- Mantonakis A, Rodero P, Lesschaeve I, Hastie R (2009b) Order in Choice. Psychological Science, 20(11): 1309-1312.

- Biswas D, Labrecque LI, Lehmann DR, Markos E (2014) Making Choices While Smelling, Tasting, and Listening: The Role of Sensory (Dis)similarity When Sequentially Sampling Products. Journal of Marketing, 78(1): 112-126.

- Mead KML, Ball LJ (2007) Music tonality and context-dependent recall: The influence of key change and mood mediation. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(1): 59-79.

- Van der Zwaag MD, Westerink JHDM, van den Broek EL (2011b) Emotional and psychophysiological responses to tempo, mode, and percussiveness. Musicae Scientiae, 15(2): 250-269.

- Bryant PE, Bradley L, Maclean M Crossland J (1989) Nursery rhymes, phonological skills and reading. Journal of Child Language, 16(2): 407-428.

- Bergman Nutley S, Darki F, Klingberg T (2014) Music practice is associated with development of working memory during childhood and adolescence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7: 926.

- Blum LD (2013) Music, Memory, and Relatedness. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 10(2): 121-131.

- Mullen G (2017) More Than Words: Using Nursery Rhymes and Songs to Support Domains of Child Development. Journal of Childhood Studies, 42(2): 42.

- Persico G, Antolini L, Vergani P, Costantini W, Nardi MT, et al. (2017) Maternal singing of lullabies during pregnancy and after birth: Effects on mother-infant bonding and on newborns’ behaviour. Concurrent Cohort Study. Women and Birth, 30(4): e214-e220.

- Lindsay DS, Wade K, Hunter M, Read J D (2004) Adults’ memories of childhood: Affect, knowing, and remembering. Memory, 12(1): 27-43.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...