Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Human Resource Management Practices, Affective Commitment and Performance in the Organizations Colina Resort, Clauangel and Radio Catumbela in Benguela, Angola Volume 8 - Issue 5

Angelina Pinto1, Ana Palma-Moreira1* and Ana Paula2

- 1Faculty of Science and Technology, European University, Quinta do Bom Nome, Estr. da Correia 53, 1500-210 Lisbon, Portugal

- 2Instituto Superior de Ciências da Educação de Benguela, Angola

Received: May 19, 2025; Published: May 27, 2025

Corresponding author: Ana Palma-Moreira, Faculty of Science and Technology, European University, Quinta do Bom Nome, Estr. da Correia 53, 1500-210 Lisbon, Portugal.

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2025.08.000297

Abstract

Purpose: The main objective of this study is to analyse whether human resource management practices affect the levels of organizational commitment and performance of employees at Colina Resort, Claulangel, and Radio Catumbela. In addition, an attempt was made to determine whether affective commitment is positively and significantly associated with the perception of employee performance.

Design/methodology/approach: This study’s sample consists of 80 individuals, employees of the Colina Resort, Clauangel, and Radio Catumbela organizations in Benguela, Angola. Methodologically, this is an exploratory-descriptive type of research, with a fundamentally quantitative approach centred on the interpretation of data obtained through the application of a questionnaire survey.

Findings: The results show that human resource management practices are positively and significantly associated with affective commitment and perceived performance. However, contrary to expectations, the association between affective commitment and perceived performance was insignificant.

Limitations: The main limitation of this study is the small sample size.

Practical Implications: On a practical level, organizations can use the results of this study to optimize their people management practices. Implementing effective human resource management practices improves employee performance and increases affective commitment, especially among those with stable contracts. Companies should, therefore, focus on management strategies that promote a favourable work environment and stimulate employees’ emotional commitment, regardless of their contractual situation.

Originality: The results show that human resource management practices are positively and significantly associated with affective commitment and perceived performance. However, contrary to expectations, the association between affective commitment and perceived performance was insignificant.

Keywords: Human Resources Management Practices; Affective Commitment; Perceived Performance; Quantitative Study; Small Organisations; Angola

Introduction to Force-based Nightmare

The success of organizations in meeting their established objectives is intrinsically linked to the motivation of existing human resources. These elements are essential in influencing the creation of strategies that build an organization’s competitive advantage, leaving it in a favourable position in relation to its competitors [1]. Machado et al. [2] believe that “managing people means giving them opportunities to feel or stay motivated.” Nevertheless, organizations must recognize the importance of recognizing their employees’ abilities and potential for development, as not everyone has the same conditions. The skills obtained will provide the expected return, contributing to the company’s better performance and productivity. This reality needs to be known by all managers. This situation leads us to reflect on the extent to which managers in our companies have mastered this principle. One of the main causes of a lack of commitment on the part of employees is a lack of clarity and trust because their bosses are not interested in their wellbeing, forgetting that a company will only be strong if its employees are strong. In this context, the choice of topic is justified by the fact that we found that the Colina Resort company in Catumbela is not concerned with training its human resources; work is valued more and human capital is not invested in, thus causing a certain demotivation; the lack of a less comprehensive standard of its own, and how the company adjusts its activities, the workers and the surrounding environment do not allow it to evolve. There is a lack of commitment, clarity and trust between employees. That is why it is important to carry out an in-depth study so that the company can set its own standards and not the same ones that already exist. Initially, we found that the apparent dissatisfaction among the workers may be influenced by the environment and the insecurity that the company offers its employees.

It is important to study variables such as Human Resource Management Practices, Organizational Commitment, and Employee Job Performance to better understand employee commitment. Therefore, this dissertation’s theme is human resource management practices, affective organizational commitment and the performance of workers at the companies Colina Resort in Catumbela, Clauangel Centro de Estudos and Radio Catumbela. Colina Resort is an organization that provides services in hospitality and tourism located in Morro de São Pedro in Catumbela in the province of Benguela. Clauangel Centro de Estudos is a tutoring centre located in Benguela, and Radio Catumbela is a radio station that focuses on music. Given the problematic situation described above, we raised the following research problem:

What is the perception of the human resource management practices of the employees of the companies Colina Resort, Clauangel and Radio Catumbela in Benguela, Angola?

What is the current state of affective organizational commitment and perceived performance of workers at Colina Resort, Clauangel and Radio Catumbela in Benguela, Angola?

Literature Review

Human Resources Management Practices

The literature states that supportive human resource management practices (HRMPs) affect organizational outcomes through employee behaviours and attitudes [3]. Good HRMPs increase organizational effectiveness through conditions in which employees feel highly committed to the organization and strive to achieve the organization’s goals [3]. From the perspective of Sousa et al. [4], HRMPs help organizations improve their ability to attract and retain employees with the skills best suited to the organization’s objectives, stimulate behaviour aligned with the organization’s strategic objectives, and adopt remuneration systems associated with the development of individual skills, team performance, and the organization as a whole. The effects of HRMPs are much more significant when combined in different ways than when the practices are explored individually, as their combination makes them coherent.

Several studies point out that the combination of flexible working practices, rigorous candidate selection, high-quality training and development, merit-based performance appraisal and continuous development, competitive pay, and a comprehensive benefits package contributes significantly to increasing employees’ affective commitment [5]. When implemented in an integrated and synergistic manner, these practices help create a work environment that values and supports employees. As a result, workers who feel more committed tend to stay with the company longer than those who don’t [6,7]. Therefore, investing in these practices strengthens employees’ emotional bond with the organization and contributes to long-term talent retention.

Affective Commitment

Affective Commitment develops through past work experiences that mainly satisfy the employee’s psychological needs (e.g. equal pay, good interpersonal relations, role clarity), leading them to feel comfortable within the organization and competent in the performance of their job (feedback, challenge, autonomy, perception of fairness in the distribution of rewards and participation in the decision-making process [8,9]. The importance of Commitment to the structure and functioning of groups and organizations means that this concept has been widely studied in organizational behaviour. However, various studies show that Commitment is not uniform and presents different interpretations. Over time, this has made organizational Commitment an increasingly complex concept with multiple dimensions.

For an organization to stand out in a highly dynamic and competitive environment, it is crucial that leaders understand and promote the Commitment of their employees. According to Silva et al. [10], this requires a constant focus on assessing organizational Commitment, which can be done through climate surveys, informal conversations and observing employee involvement in company projects and initiatives. In recent years, increasing competition between organizations has raised the need for deeper employee involvement, which translates into dedication to implementing strategies, goals and objectives to ensure the company’s survival [11]. Employee commitment is seen as a key factor, reflecting not only motivation and enjoyment at work but also exemplary behaviour and dedication to work [10]. Organizations are looking for candidates who, in addition to having the necessary technical skills, also show skills in communication, relationships and dedication, contributing to their Commitment to the company [10].

Rego and Souto [12] note that Commitment can impact various aspects of the organization, including punctuality, intention to remain in the position, attendance, and positive attitudes towards change. This Commitment is crucial for optimizing capabilities, creating opportunities and improving productivity [13]. In addition, Commitment contributes to reducing absenteeism, waste, and turnover and improves the quality of work [14-16]. Organizations often reward the most committed employees with better career opportunities and salary increases, highlighting the importance of maintaining a high level of Commitment to achieve organizational success [17,18].

Human Resource Management Practices and Affective Commitment: To promote affective commitment and achieve excellent results, Human Resources practices are fundamental [19]. We believe that commitment is based on reciprocity: for the employee to dedicate themselves and contribute to the company’s success, the company’s values must align with the values the employee seeks. This way, employees feel motivated to give their best and contribute to the organisation’s well-being. Good human resource management practices, including developing employees’ skills, boost their emotional commitment to their work organisation [20]. This relationship can be interpreted in the light of the Social Exchange theory [21] or the Reciprocity Norm [22], i.e. when employees have a high perception of human resource management practices, they reciprocate by developing a greater affective commitment to the organization where they work. In a study by Perumal et al. [23], the authors concluded that there is a positive and significant association between human resource management practices and affective commitment. Davis et al. states that in a context of uncertainty; organizational leaders must develop good human resource management practices to increase employees’ affective commitment to the organization. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated.

Hypothesis 1: Human resource management practices are positively and significantly associated with affective commitment.

Performance

Job performance has been considered a dependent variable of great interest since an organization’s objectives are measured in terms of it [24]. Its individual component is “an indicator of how well an employee performs the tasks related to their job” [25]. Cunha et al. [26] state that performance can be understood as “a comparison between individual performance expectations and actual performance” (p.887). Randhawa [24] also adds that it is “what individuals do and is observable” (p.47). According to Cunha et al. [26], the concept of individual performance is distinguished from productivity in that the latter is more commonly used in organizational studies and can be conceived “as the degree to which results approach objectives” - effectiveness - or “as the relationship between results and the resources needed to achieve them” - efficiency (p. 887).

Human Resource Management Practices and Performance: Human resource management practices involving performance appraisal, professional development, and a fair approach to pay significantly impact performance. Greenberg [27] and Adams [28] point out that perceived fairness in pay affects performance, with employees adjusting their performance according to perceived fairness or unfairness. Human resource management practices must be effective and comprehensive to optimise performance and satisfaction, including incentives, promotions and a positive working environment [29,30]. In a study by Alsafadi & Altahat [31], the authors also concluded that human resource management practices positively impact employee performance. Also, in a study by Alqudah et al. [32], the authors found a positive association between human resource management practices and employee performance. In line with the conclusions of these studies, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 2: Human resource management practices are positively and significantly associated with performance.

Affective Commitment and Performance: Affective commitment is crucial to performance. Turner & Chelladurai [33] found that commitment explains objective and subjective performance variation. Organizations with high levels of commitment generally excel in three areas: performance alignment, psychological alignment, and capacity for learning and change [34]. In addition to commitment, employee involvement is another important variable. Rich et al. [35] showed that engagement mediates the relationship between congruent values, perceived organizational support, task performance, and organizational citizenship behaviours. Mercurio [36] considers affective commitment, i.e., the emotional attachment to the organization, to be an important essence of organizational commitment in boosting employee performance. This is the reasoning that leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Affective commitment is positively and significantly associated with performance.

The research model summarises the hypotheses formulated in this study:

Method

Data collection procedure

Eighty participants working in three organizations in Benguela, Angola, voluntarily participated in this study. The sampling process was non-probabilistic, convenient, and intentional [37]. The questionnaires were delivered in sealed envelopes to the employees of the three organizations. The answers were collected 30 days after the delivery. Before starting to answer the questionnaire, the participants were given informed consent, which guaranteed the confidentiality of their answers so that they could decide whether they wanted to take part in the study. The questionnaire included sociodemographic information to characterize the sample. In addition to these questions, participants were asked to respond to three different scales: human resource management practices, affective commitment, and performance. Data collection took place between March and April 2024.

Participants

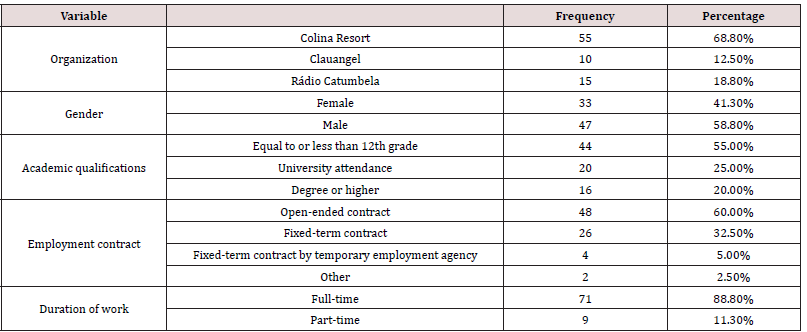

The sample in this study consisted of 80 participants aged between 20 and 57, with an average age of 30.40 and a standard deviation of 7.82. Table 1 summarizes the other sociodemographic variables (Table 1).

Data analysis procedure

Once the data had been collected, it was entered into a database in the SPSS Statistics 29 software. The first step was to test the reliability of the instruments used in this study by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. In organizational studies, this value should be higher than .70 [38]. Next, one-sample Student’s t-tests were carried out to study the descriptive statistics of the variables under study. To study the effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study, Student’s t-tests for independent samples and One Way ANOVA were carried out. Pearson’s correlations were used to study the association between the variables under study. Linear regressions were used to test the hypotheses.

Instruments

To study the perception of human resource management practices, we used the instrument developed by Cesário [39], consisting of 21 items (Appendix A). The items are classified on a five-point Likert-type scale: “1” strongly disagree, “2” disagree, “3” neither agree nor disagree, “4” agree and “5” strongly agree. This instrument has seven dimensions: integration and welcome, training, performance evaluation, career, rewards, communication and celebration. Regarding internal consistency, it has a Cronbach’s alpha of .92.

To study performance, we used the four-item instrument developed by Williams & Andreson [40]. The items are classified on a five-point Likert-type scale: “1” strongly disagree, “2” disagree, “3” neither agree nor disagree, “4” agree, and “5” strongly agree. The performance scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of .76. To study affective commitment, we used the six-item affective commitment dimension of the instrument developed by Meyer and Allen [41]. The items are classified on a seven-point Likert-type scale: “1” strongly disagree, “2” disagree, “3” somewhat disagree, “4” neither agree nor disagree, “5” somewhat agree, “6” agree, and “7” strongly agree. Affective commitment has a Cronbach’s alpha of .75.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the variables under study

Initially, descriptive statistics were carried out on the variables under study to understand the position of the answers given by the participants in this study. The averages of the answers given by the participants in this study are significantly above the central point of the instruments (Table 2). The central point of the HRMP and performance instruments is “3,” and the affective commitment instrument is “4.” Thus, it can be concluded that the participants have a high perception of HRMP and performance and a high affective commitment (Table 2).

Effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study

Female participants have a higher perception of PGRH and a greater affective commitment than male participants (Figure 2).

Participants with a university degree and a bachelor’s degree or higher have a higher perception of PGRH and a greater affective commitment than participants with a 12th-grade degree or lower (Figure 3).

Employees with a fixed-term contract with a temporary employment agency have the lowest perception of the HRMP and performance. Employees with open-ended contracts have the highest affective commitment (Figure 4).

When comparing the answers given by the employees of the different organizations, it was found that the employees of Clauangel and Rádio Catumbela have a significantly higher perception of HRMP than the employees of the Colina Resort hotel (F (2, 77) = 7.75, p < 0.001) (Figure 5). The affective commitment of Rádio Catumbela employees is significantly higher than that of other employees (F (2, 77) = 23.68, p < 0.001) (Figure 5).

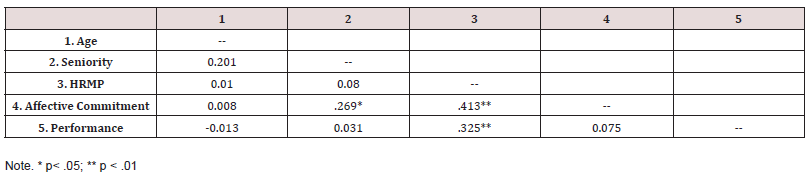

Association between the variables under study

The Pearson correlation results indicate that age is not significantly correlated with any of the variables under study (Table 3). Length of service in the organization was only positively and significantly correlated with affective commitment. Participants who have been with the organization the longest have the greatest affective commitment (Table 3). HRMPs are positively and significantly correlated with performance and affective commitment. Participants with a better perception of HRMP are those with greater affective commitment and a better perception of performance (Table 3). Affective commitment was not correlated with perceived performance (Table 3).

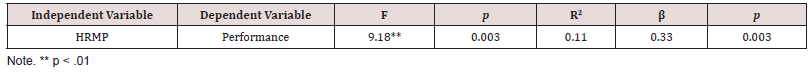

Hypotheses

Hypotheses were tested using simple linear regressions after testing the respective assumptions. The perception of HRMP has a positive and significant effect on the perception of performance (β = .33, p = .003), which indicates that the better the perception of HRMP, the better the performance. The model explains 11% of the variability in performance (Table 4). This hypothesis was supported (Table 4).

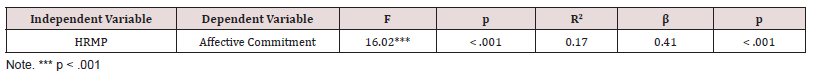

The perception of HRMP has a positive and significant effect on affective commitment (β = .41, p < .001), which indicates that the better the perception of HRMP, the better the performance. The model explains 17% of the variability in performance (Table 5).

This hypothesis was supported (Table 5).

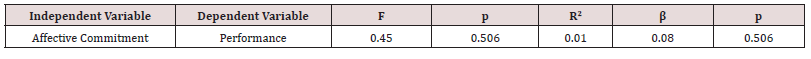

Affective commitment has no significant effect on performance (Table 6).

The results do not support hypothesis 3 (Table 6).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of HRMP on affective commitment and performance and the effect of affective commitment on performance. It was found that HRMPs have a positive and significant effect on performance. These results align with the literature since, to optimize performance, HRMPs must be effective and efficient [29,30]. HRMPs also have a positive and significant effect on affective commitment, in line with the literature’s assertion that they are fundamental to promoting affective commitment [19]. Contrary to the literature, affective commitment does not significantly affect performance. Turner and Chelladurai [33] state that commitment explains the variation in both objective and subjective performance. As for the type of employment contract, most participants (60%) have open-ended contracts, which suggests more excellent job stability for this portion of the group. In contrast, a significant proportion (32.5%) are employed on fixed-term contracts, which may indicate a more temporary work situation or one with fewer long-term guarantees. These employees with fixed-term contracts have shown the least emotional commitment to the organization where they work. Fixed-term contracts with temporary work companies account for 5% of cases, which shows even less stability since these contracts are generally associated with temporary or provisional positions.

According to Guest [42], these employees, often seen as temporary or provisional, can experience low loyalty to the organization. Turnover and uncertainty can trigger greater stress and lower motivation, negatively impacting affective commitment and performance. This phenomenon reflects the reality of many workers in temporary employment schemes, where the bond with the company is less solid, resulting in low commitment and productivity [43]. This is the case with Clauangel’s employees. In conversations with them, we realized that they are only there for alternative employment; in the event of another opportunity appearing in the state, they would leave the company immediately. This situation means that the promoters do not bother to establish long-term contracts. Finally, the 2.5% who have another type of contract indicate a small diversity in contracting forms, which may include atypical or less common agreements.

These data suggest a panorama of job security for the majority of workers but also reveal a significant portion with less stable ties, which can impact their economic security and long-term planning. Studies such as Chambel’s [19] suggest that temporary contracts can lead to less identification with the organization. These employees often see the job as a stepping stone to other opportunities rather than a long-term commitment. The lack of a contract can also reduce commitment and willingness to achieve high levels of performance, as workers may not feel valued or secure enough to fully invest in their roles. Analysis of the data presented reveals a significant discrepancy in the distribution of working hours among the study participants. Specifically, 88.8% of the participants (71) work full-time, while only 11.3% (9) work part-time. This disparity could indicate various situations, such as the predominance of jobs that demand a greater workload or participants’ preference for jobs that offer greater stability and benefits associated with fulltime work. It could also suggest that there are few opportunities or less attractiveness for part-time jobs within the context analysed. In addition, this difference may reflect the economic needs of the participants, where a significant majority may depend on a full workload to sustain their standard of living. Detailed analysis of these variables could provide a deeper understanding of the reasons behind this discrepancy and its implications in the context studied.

These results confirm our initial idea because we found that at the Colina Resort company in Catumbela, there is no concern for the training of its human resources; work is valued more and human capital is not invested in, thus causing a certain demotivation of the lack of a less comprehensive standard of its own. How the company adjusts its activities, the workers, and the surrounding environment do not allow it to evolve. There is a lack of commitment, clarity and trust among employees.

Limitations and Future Research

The main limitation was the small size of the sample. At the Colina Resort, around 100 paper questionnaires were handed out, but only 55 responded. Of the 18 employees at Rádio Catumbela, 15 answered the questionnaire. At Clauangel, ten out of 12 employees responded. The small size of the sample limits the generalization of the results to other organizational contexts since a more robust sample could provide a more representative view. Another limitation is that a closed-ended questionnaire was used, which may have biased the results. This data collection format limits the possibility of employees expressing more detailed opinions or providing qualitative information that could enrich the analysis. Using more diverse data collection methods, such as semistructured interviews or open-ended questionnaires, would be interesting in capturing deeper insights into employees’ perceptions of HRMPs, affective commitment, and performance. It is suggested that future research extend this study to larger organizations. Another relevant point for future research would be to explore other factors that can influence performance in addition to affective commitment, such as organizational climate, leadership style, and extrinsic motivation. This would help clarify the relationship between affective commitment and performance, which in this study was not significant. Finally, it would be pertinent to compare different sectors or industries to see if the effects of HRMP and affective commitment vary according to the type of organization or work environment. This type of analysis could further enrich our understanding of the applicability of HRMPs in different contexts.

Practical implications

This study’s results significantly contribute to both the theoretical and practical fields of human resource management. On a theoretical level, the data reinforces the idea that effective human resource management practices (HRMP) have a direct and positive impact on organizational performance and affective commitment, confirming the positions defended by authors such as Katou & Budhwar [29] and Chambel [19]. The research also adds to the debate on the role of affective commitment, suggesting that, in specific contexts, it may not be a determining factor for performance, which opens up new perspectives for studies on the relationship between emotional commitment and efficiency at work. On a practical level, organizations can use the results of this study to optimize their people management practices. Implementing effective HRMPs improves worker performance and increases affective commitment, especially among those with stable contracts. Therefore, companies should focus on management strategies that promote a favourable working environment and stimulate employees’ emotional commitment, regardless of their contractual situation. In addition, the results warn of the need to review hiring and retention policies since employees with less stable contractual ties tend to show less emotional commitment.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to analyze the impact of Human Resource Management Practices (HRMP) on employees’ affective commitment and performance and assess the relationship between affective commitment and performance. The results obtained make important contributions to the literature and organizational practice, providing insights into the influence of HRMPs in the business context. Firstly, the data confirms that HRMPs have a positive and significant effect on workers’ performance and affective commitment, corroborating the findings of authors such as Katou & Budhwar [29] and Chambel [19]. This element reinforces the importance of effective management practices, which can optimize organizational performance by promoting an environment that fosters employees’ emotional commitment to the company. From this, implementing well-structured HRMPs is essential for organizational success and talent retention.

However, contrary to what the literature suggests, affective commitment did not prove to be a significant factor in performance. In this study, employees’ emotional commitment was not a determinant of performance, contrary to what Turner & Chelladurai [33] state. This suggests that other factors may be at play, such as working conditions, extrinsic motivation, or even the nature of the tasks performed. In terms of contractual characteristics, the majority of participants had open-ended contracts, which suggests greater job security and stability. However, a significant proportion of employees (32.5%) are on fixed-term contracts, especially those with less emotional commitment to the organization. This data indicates that precarious contracts can negatively influence emotional involvement with the company, affecting performance and talent retention. In addition, there was a discrepancy in working hours between the participants, with a predominance of full-time employees (88.8%). This difference may be related to employees’ economic needs and the search for greater financial stability, which reveals important aspects for companies to consider when planning their employee retention and satisfaction strategies.

In short, this study shows that HRMPs play a crucial role in employee performance and affective commitment. However, it also suggests that affective commitment alone is insufficient to explain performance and that a more in-depth analysis of other factors may influence this relationship is needed. Thus, this work paves the way for future research exploring these variables in different contexts and providing new perspectives on human resource management. These results confirm our initial idea because we found that the Colina Resort company in Catumbela is not concerned with training its human resources; it values work more and does not invest in human capital, thus causing a certain demotivation; the lack of a less comprehensive standard of its own, and how the company adjusts its activities, the workers and the surrounding environment do not allow it to evolve. There is a lack of commitment, clarity and trust between employees. Clauangel’s employees work under temporary employment schemes, which weaken their bond with the company, resulting in low commitment and productivity.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- Barney JB (1991) Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17: 99-120.

- Machado DF, Costa M, Lima L (2014) Gestão de desempenho: Metodologias e desafios. São Paulo: Atlas.

- Whitener EM (2001) Do high commitment human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modelling. Journal of Management, 27(5): 515-535.

- Sousa G, Almeida P, Gonçalves D (2006) A análise do desempenho organizacional. Porto Editora.

- Takeuchi R, Lepak DP, Wang H, Takeuchi K (2007) An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4): 1069-1083.

- Oliveira MS, Costa M (2016) Práticas de gestão de pessoas e a percepção dos colaboradores. Revista Brasileira de Administração, 23(2): 101-112.

- Rocha F, Honório L (2015) Comprometimento organizacional: Impacto das práticas de gestão de pessoas. Revista Administração em Diálogo, 17(1): 87-103.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1991) A three-component model of organizational commitment.

- Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L (1998) Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1): 20-52.

- Silva G, Gallon S, Pessotto R (2017) Comprometimento organizacional e desempenho profissional. Revista de Gestão, 24(2): 41-58.

- Costa MR, Moraes LF (2007) Estabilidade no emprego e comprometimento organizacional: Uma análise na indústria tê Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 2(1): 45-58.

- Rego A, Souto S (2004) Comprometimento organizacional: Conceitos e relações com satisfação no trabalho e performance professional. Revista de Psicologia Organizacional, 5(2): 23-45.

- Lizote SA, Verdinelli MA, Nascimento AR (2017) Práticas de recursos humanos e seu impacto no comprometimento organizacional. Revista Eletrônica de Estratégia e Negócios, 10(1): 245-262.

- Stazyk EC, Pandey SK, Wright BE (2011) Understanding affective organizational commitment: The importance of institutional context. The American Review of Public Administration, 41(6): 603-624.

- Borges LO, Marques JF, Adorno J (2005) O comprometimento organizacional: Uma abordagem crí Revista de Psicologia, 11(3): 47-56.

- Reichers AE (1985) A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Review, 10(3): 465-476.

- Tavares SM (2011) Comprometimento organizacional: Uma análise longitudinal. Revista Portuguesa de Gestão de Recursos Humanos, 1(1): 101-112.

- Jesus RG, Rowe DE (2017) Adaptation and obtainment of evidence for the validity of the “Scale of Perceived Sacrifices Associated with Leaving (the organization)” in the Brazilian context: a study among teachers of basic, technical, and technological education. Revista de Administração, 52: 93-102.

- Chambel MJ (2012) Comprometimento organizacional: Uma abordagem à relação dos trabalhadores temporários e permanentes com a organizaçã Revista de Psicologia, 6(2): 101-115.

- Moreira A, Tomás C, Antunes A (2024) The Mediating Effect of Affective Commitment on the Relationship between Competence Development and Turnover Intentions: Does This Relationship Depend on the Employee’s Generation? Administrative Sciences, 14: 97.

- Blau PM (1964) Justice in Social Exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34: 193-206.

- Gouldner AW (1960) The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review, 25: 161-178.

- Perumal J, Fox RJ, Balabanov R, Laura J Balcer, Steven Galetta, et al. (2019) Outcomes of natalizumab treatment within 3 years of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a prespecified 2-year interim analysis of STRIVE. BMC Neurol 19: 116.

- Randhawa G (2007) Work Performance and its Correlates: An Empirical Study. Vision, 11(1): 47-55.

- Skinner HB, Barrack RL, Cook SD (1984) Age-related decline in proprioception. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 184: 208-211.

- Cunha MP, Rego A, Cunha R, Cabral-Cardoso C (2016) Manual de comportamento organizacional e gestão (6th ed.) RH Editora.

- Greenberg J (1988) Equity and workplace status: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(4): 606-613.

- Adams JS (1965) Inequity in social exchange. In: L Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press, 2: 267-299.

- Katou AA, Budhwar PS (2012) The effects of human resource management policies on organizational performance in Greek manufacturing firms. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(5): 1-35.

- Stumpf R, Martin Frank, Joachim Schönfeld, Brian A Haley (2010): Late Quaternary variability of Mediterranean Outflow Water from radiogenic Nd and Pb isotopes. Quaternary Science Reviews, 29(19-20): 2462-2472.

- Alsafadi Y, Altahat S (2021) Human Resource Management Practices and Employee Performance: The Role of Job Satisfaction. Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business 8: 519-529.

- Alqudah IHA, Carballo-Penela A, Ruzo-Sanmartín E (2022) High-performance human resource management practices and readiness for change: An integrative model including affective commitment, employees’ performance, and the moderating role of hierarchy culture. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28 (1): 100177.

- Turner BA, Chelladurai P (2005) Organizational and occupational commitment, intention to leave, and perceived performance of intercollegiate coaches. Journal of Sport Management, 19(2): 193-211.

- Beer M (2009) High commitment, high performance: How to build a resilient organization for sustained advantage. Jossey-Bass.

- Rich BL, Lepine JA, Crawford ER (2010) Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3): 617-635.

- Mercurio ZA (2015) Affective Commitment as a Core Essence of Organizational Commitment: An Integrative Literature Review. Human Resource Development Review, 14(4): 389-414.

- Trochim WMK (2000) The research methods knowledge base (2nd ed.) Atomic Dog Publishing.

- Bryman A, Cramer D (2003) Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows (3ª ed.) Oeiras: Celta.

- Cesário F (2015) Employes Perceptions of the Importance of Human Resources Management Practices. Research Journal of Business Management 9(3): 470-479.

- Williams LJ, Anderson SE (1991) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviours. Journal of Management, 17(3): 601-617.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1997) Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Sage Publications.

- Guest DE (2004) The psychology of the employment relationship: An analysis based on the psychological contract. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(4): 541–555.

- De Cuyper N, De Witte H (2007) Job insecurity in temporary versus permanent workers: Associations with attitudes, well-being, and behaviour. Work & Stress, 21(1): 65-84.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...